To this day, however, a thin line of doubt persists. A positive outcome of this experience at this abandoned camp was that we were permitted to stay indoors, sleeping on the wooden floor for the remainder of the night. This was our first time indoors to sleep and we thought of that as a luxury at this time; although we would not have thought of it as a luxury a week ago. The following morning we were ‘rousted’ out before dawn to continue our march in the ever-increasing fall of snow, with temperatures dropping daily. The long, winding, snake-like column of soldiers had now raised the numbers to about 6000. We had lost some men along the way when they were shot for falling too far behind in the line, had just given up hope, or were suffering from unattended wounds that finally infected and killed them. We didn’t always know what happened to others, nor did we know what their problems were, nor did the guards encourage any long-range communication between us.

Some men may have escaped, although we would not get word to this effect since it would create new alertness on the part of the German guards and possibly bring a reprisal on those of us who were still in captivity. There was little to occupy the time as we moved; except to get better acquainted with the men nearest you in the line. Not all friends were together. It was a rare privilege when you saw someone you had known and were able to start the next day’s march with him. While many of us were in the same unit of the Army before capture, we were separated during all of the confusion of battle and the subsequent escape from machine-gun slaughter. It constantly ran through my mind that a childhood buddy I had admired had been shot down over Germany two years before this time and I wondered if it would ever be possible to run across him in a country as large as this, under these circumstances – the chances seemed very slim. Although the weather had gotten very cold, and there was much snow from time to time, the visibility in the sky was such that the Allied planes, fighters, and bombers were able once again to take to the air. While this was a comforting thought, because to our minds this brought us close to the end of the war and our liberation, we had not reckoned with the fact that while on the ground and seen from the air, our pilots did not know us from the German who might be moving to new positions.

Our first taste of the reality of our plight came suddenly at the dawn of the 8th day. We were cheering loudly because we had spotted the plane as one of ours, but the pilot had no way of knowing we were prisoners of war, and as a result came in with guns blazing, strafing the entire length of the column. Instinctively we moved to the left and right out of the line of fire, but the slower and less lucky men were killed outright or wounded. As fate would have it we lost surprisingly few men on that pass but we quickly concluded that we had to do something before the plane returned or another one showed up. A command decision, by several of us, quickly rallied the men into a huge, human PW, the initials for Prisoners of War, which could be seen from the air. You have never seen men move so fast, nor obey orders so quickly. Everyone knew something had to be done fast. The success of that maneuver was apparent when the next plane coming in on us hesitated, banked to the right, waggled his wings, and best of all did not shoot at us. It became immediately apparent to us that he communicated this information to others because from that point on planes looked us over before shooting and, on seeing our POW made of soldiers, would waggle wings and move on. The German guards did not object to this maneuver because it offered them the same protection we were getting. Not much later in the war, however, we were forbidden, by order of the German High Command to form our PW. They wanted to confuse our pilots who were shooting at everything on the ground that moved except POW groups. There was a rumor that German soldiers were using the same idea of PW with their foot soldiers to avoid being strafed by Allied planes.

As a result of not being able to protect ourselves, the loss of men was tragically increased as we proceeded to what was now referred to as our entertaining point; to be moved further into Germany and presumably to a Prisoner of War Camp. The loss of our ability to form our PW was devastating to our morale. Any planes, now even at a distance, brought fear to our hearts. This carried on for months after the war was over and after I had returned to Akron, Ohio, my hometown.

I was dressed up in a suit and walking in a downtown area in Akron, when an unthinking, stupid pilot, buzzed the main street. Still reacting as I had in Germany months before, I moved to my right which put me in the middle of the street, and fell flat on my face, covering my head. I was embarrassed as I saw the reaction of dozens of people who were looking on.

I was dressed up in a suit and walking in a downtown area in Akron, when an unthinking, stupid pilot, buzzed the main street. Still reacting as I had in Germany months before, I moved to my right which put me in the middle of the street, and fell flat on my face, covering my head. I was embarrassed as I saw the reaction of dozens of people who were looking on.

Crisis over Train Travel

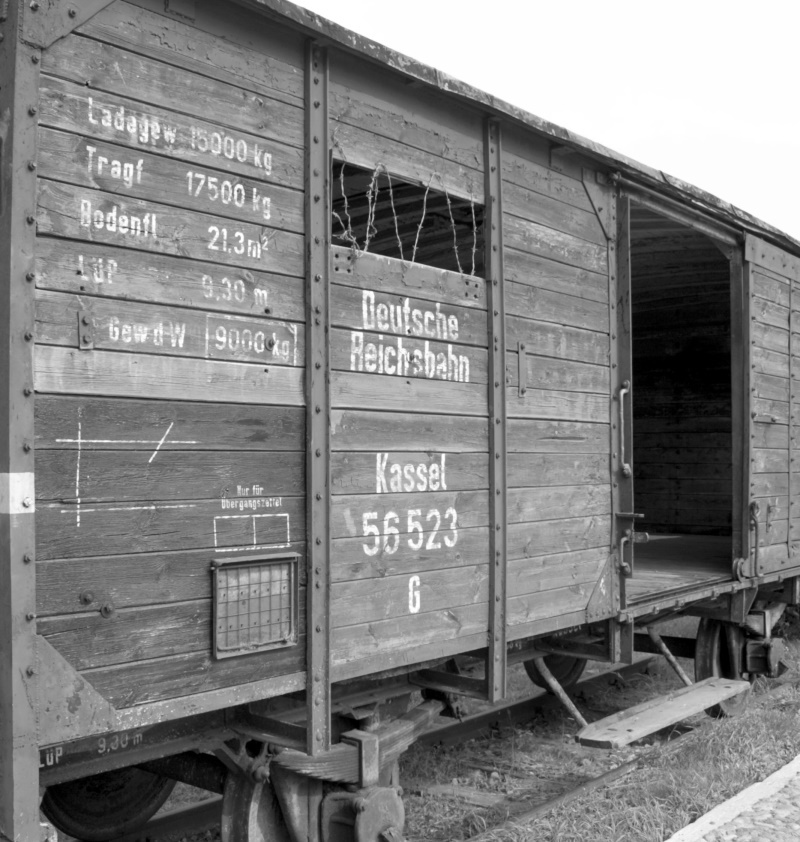

On the days following our interrogation, bathing, and being stripped of our last possessions; we were marching along in an uneventful, boring manner. The countryside was bleak because it was winter but the knowledge that we were in a foreign country brought with it a kind of excitement that we might see something new and different, instead of just the back of the soldier in front of us. The feeling which kept us going was that just over the next hill a town might appear or there might be a farmhouse offering food to our hungry mob or we might even see the train which we were now anticipating seeing at any time. It was going to be a relief to ride for a while and have food brought to us, hopefully, hot food to remove some of the chills from our bones. Our hope of getting on a train and riding was a very real vitalizing goal which seemed to make the walking easier and the cold and hunger easier to bear.

About noon we were treated to the long-awaited sight. The train was there just ahead; just standing and waiting for the approximately 6000 foot-weary, hungry soldiers to get aboard and be taken to civilization, where they didn’t forget to feed you and provide a bunk for our weary bones. Perhaps I am being a little hard on the German guard contingency. They didn’t have any way to get food for this many men and no one in the high command of the German Army seemed to care one way or the other. In Spartan fashion, we accepted the resulting pain of it all. It was easy to forgive all of the misery we had endured when the train was in sight. We began to joke and our spirits were much lighter. Even the cold didn’t seem so bad and we were certain that in a small country like Germany, we would rather quickly be at an Army Post, a Prison Camp, or some facility where they could take care of us properly.

The thrill of anticipation produced more out-and-out adrenaline and we were running toward the train. The engine of the train was rather small by American standards but we were more concerned when we noted that there were not many cars attached to it. From what we could count on the cars and knowing that there were about 6000 of us, we soon realized that we were not going to be riding in great comfort. Still, a little discomfort was better than walking and faster. We were lined up and herded into the cars which had only the usual sliding doors of a cattle car for an opening. Those of us who went in first soon found ourselves crushed against the back wall of the car and having to stand up. There were so many men in each car there was no way you could either sit or fall. After what seemed to be an endless time and with our tendency to claustrophobia mounting, we heard a shout, evidently that all was clear because we began to move. What a glorious sensation, moving without trying. I have to say one good thing about being packed in the cars as tight as we were, we were really warm for the first time in many days and had hope.