Document Source: Gunter G. Gillot (Doc Snafu), 1984, US Airborne ETO-MTO 1940-1945, Foxmaster Publishing, (French), with Gen William T. Ryder, Gen William P. Yarborough, Gen Matthew B. Ridgway, Gen William M. Miley, Gen James M. Gavin, and many veterans (from both sides) of the World War Two Airborne Warfare.

FOREWORD

Most of the text deployed below is extracted from a book I wrote in 1986, US Airborne 1940-1945 ETO-MTO (Collector’s Academy Press). This was before the Internet. During this period, collecting information and images for the conception of a book was a real endeavor. By chance, while I was doing research myself in the Forest along the Siegfried Line in the vicinity of Underbeth, I had the good fortune to meet an American Army veteran who was also busy researching details of the military operations that had taken place in the exact place where we were. It was while chatting with this veteran that I learned that he too was busy writing a book, A Time for Trumpets, and while we were sitting on the edge of a foxhole that one of his men had dug for him on December 14, 1944, he was, in fact, a

Most of the text deployed below is extracted from a book I wrote in 1986, US Airborne 1940-1945 ETO-MTO (Collector’s Academy Press). This was before the Internet. During this period, collecting information and images for the conception of a book was a real endeavor. By chance, while I was doing research myself in the Forest along the Siegfried Line in the vicinity of Underbeth, I had the good fortune to meet an American Army veteran who was also busy researching details of the military operations that had taken place in the exact place where we were. It was while chatting with this veteran that I learned that he too was busy writing a book, A Time for Trumpets, and while we were sitting on the edge of a foxhole that one of his men had dug for him on December 14, 1944, he was, in fact, a  Lieutenant, a Company Commander, that he had taken part in the combats and finally that his name was Charles B. MacDonald. It was at this time that we gave birth to a long-lasting and sincere friendship which later would be very useful to me since he suggested that he could become, in some way, a kind of spiritual father in the field that interested me, Military History.

Lieutenant, a Company Commander, that he had taken part in the combats and finally that his name was Charles B. MacDonald. It was at this time that we gave birth to a long-lasting and sincere friendship which later would be very useful to me since he suggested that he could become, in some way, a kind of spiritual father in the field that interested me, Military History.

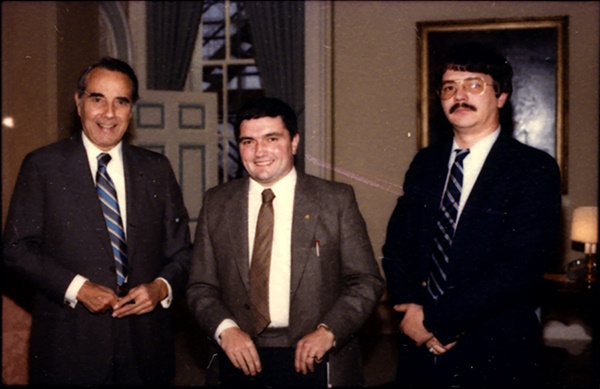

Thus, each time he returned to Europe, most often accompanied by a group of veterans of his wartime Division, the 2nd Infantry Division, he contacted me and I could at leisure participate in these multiple visits literally immersed in the year 1944 and the Battle of the Bulge. I was also repeatedly invited to his home on Columbia Pike where he spent a lot of time showing me around Arlington Cemetery, the Capitol, and the Senate with a special visit and a coffee with the Honorable Sen Bob Dole, another World War Two veteran. He also showed me, particularly during the evening while singing songs not to be named in this foreword, the little hot roads of Washington DC and those magnificent ladies yelling at us things I won’t tell you about.

Thus, each time he returned to Europe, most often accompanied by a group of veterans of his wartime Division, the 2nd Infantry Division, he contacted me and I could at leisure participate in these multiple visits literally immersed in the year 1944 and the Battle of the Bulge. I was also repeatedly invited to his home on Columbia Pike where he spent a lot of time showing me around Arlington Cemetery, the Capitol, and the Senate with a special visit and a coffee with the Honorable Sen Bob Dole, another World War Two veteran. He also showed me, particularly during the evening while singing songs not to be named in this foreword, the little hot roads of Washington DC and those magnificent ladies yelling at us things I won’t tell you about.

On the last day of my last visit, he decided to take me to the Office of the Chief of Military History where he asked the Officer in charge to write me a letter, he called this a ‘Door Opener’, in order to facilitate the contact with all these people, mostly Senior Officers that I was planning to contact for my book in preparation on Parachutes and Paratroopers. When I returned to Belgium, I obviously used this precious document, and each time I wrote a letter I always had the expected response, and often the letters contained much more than what I had asked for.

The first to contact was obviously James Gavin. With the copy of the letter from the CMH, the response became assured without the slightest problem and I was even able to walk a small part of the way with the General until the last letter from his wife telling me that James was not going well at all right now. Shortly after Gen James M. Gavin left us permanently. Let him be reassured, however, we, the little people of Belgium, will never forget him. Always driven by my quest for information, I then came into contact with William T. Ryder, the commander of the 1st American parachute Test Platoon, William P. Yarborough (509-Italy), George Jones (503-Pacific), William M. Miley (17-AB), and Matthew B. Ridgway (XVIII A/B Corps) whom I visited in the outskirts of Pittsburgh in 1986. Obviously, I met a multitude of other veterans, but in the framework of the book on which I was working, these men brought nothing else but new very strong bonds of friendship which today still persist on my side, because these men of this generation have almost all disappeared.

I am a part, like many of my friends, of this post-war generation during which the food to be put on the table every day was more important than the education likely to be given to a child. Today, at 67, I don’t blame anyone because if I left school at 13 to go work in the forest, it was my choice, a choice depending on the period, the difficulties encountered, and the unconditional support to help the family as much as possible, a single mother who worked like a madman, and a young sister who had recently joined the tribe.

The only thing I regret is not having had access to the education that would have allowed me to be much freer in my ideas and to be able to achieve the goals that I would have liked so much to achieve. But like I’ve always said trying to do something that’s beyond you and succeeding is fine. On the other hand, doing something, missing it, and starting over is the top, because ultimately the secret in this life is to move forward. George S. Patton said it himself: attack, attack, and attack again. This could ultimately translate into Avance, Avance, and keep advancing. This text was written with Google translate and my keyboard. AI wasn’t asked to do it. I use this application because I am not yet able to struggle alone with English. Who knows, maybe one day…

Gunter ‘Doc Snafu’ Gillot

March 6, 2023.

Legend and Facts

According to the legend, it seems that the first use of a device intended to slow the fall of a man in the air was made in China some 4000 years before JC. As the story told us, Shun, the Emperor himself trapped in his palace used a large umbrella to jump out of a window and landed relatively safely on the ground. An account, from the Western Han Dynasty writer Sima Qian in his book ‘Historical Records’, recounts the story of Shun, a legendary Chinese Emperor who ran away from his murderous father by climbing onto the top of a high granary. As there was nowhere to go, Shun grabbed two bamboo hats, leaped off, and glided downward to safety. Unfortunately, Channel News Network (aka CNN) was not there and we don’t have any image from this jump. It seems also that over here, in Europa, a fellow named Icarus did also some interesting tests as well as some interesting crashes. In fact, after Emperor Shun’s first Airborne test, 3500 years were needed to go further with a piece of equipment to help to slow the fall of a man into the air.

In one of his book published in 1502: Codex Atlanticus, Leonardo da Vinci presented the first draw of an engine that would have slowed down the fall on a man in the air. Please notice the part of the last sentence: ‘that would have slowed the fall of a man in the air’ as fortunately, no one ever tried this engine.

In one of his book published in 1502: Codex Atlanticus, Leonardo da Vinci presented the first draw of an engine that would have slowed down the fall on a man in the air. Please notice the part of the last sentence: ‘that would have slowed the fall of a man in the air’ as fortunately, no one ever tried this engine.

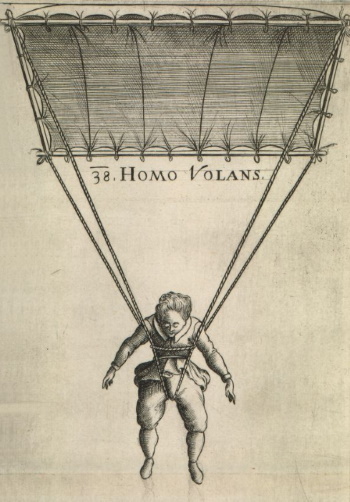

A little more than a century later, in 1616, the Dalmatian Polymath and inventor Fausto Veranzio published also a book ‘Machinae Novae’, into which, a chapter named ‘Homo Volans’ (Flying Man) reproduces Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Parachute’ with some modifications, a rectangular wooded frame with a piece of canvas fixed to it.

Let’s hope that no one ever tried this strange thing to jump from some cliff or so. This engine was used to make neither a test jump nor a wind catch but the very interesting part of Veranzio’s draw was the way he described the system to connect the man to the device, using single pieces of rope. Veranzio created the first parachute harness that (while modified) is still in use today. Isaac Newton got also involved in the project. While using da Vinci’s elementary calculations, he created the first mathematical rule to be used in relation to the size of the parachute and the weight of the paratrooper, Newtown’s Motion Laws.

Let’s hope that no one ever tried this strange thing to jump from some cliff or so. This engine was used to make neither a test jump nor a wind catch but the very interesting part of Veranzio’s draw was the way he described the system to connect the man to the device, using single pieces of rope. Veranzio created the first parachute harness that (while modified) is still in use today. Isaac Newton got also involved in the project. While using da Vinci’s elementary calculations, he created the first mathematical rule to be used in relation to the size of the parachute and the weight of the paratrooper, Newtown’s Motion Laws.

In France, Louis Sébastien Lenormand, a French Physicist at the Montpellier Faculty, invented a device and named it ‘parachute’. Into the huge book of history, Lenormand was the first human to make a witnessed descent with a parachute and is also credited with coining the term parachute French parasol-sun shield and chute-fall.

In France, Louis Sébastien Lenormand, a French Physicist at the Montpellier Faculty, invented a device and named it ‘parachute’. Into the huge book of history, Lenormand was the first human to make a witnessed descent with a parachute and is also credited with coining the term parachute French parasol-sun shield and chute-fall.

On December 26, 1783, Lenormand jumped from the tower of the Montpellier Observatory in front of a crowd that included Joseph Montgolfier (one of the two balloonists Montgolfier brothers), using a 14-foot parachute with a rigid wooden frame. His intended use for the parachute was to help entrapped occupants of a burning building or a balloon to escape unharmed.

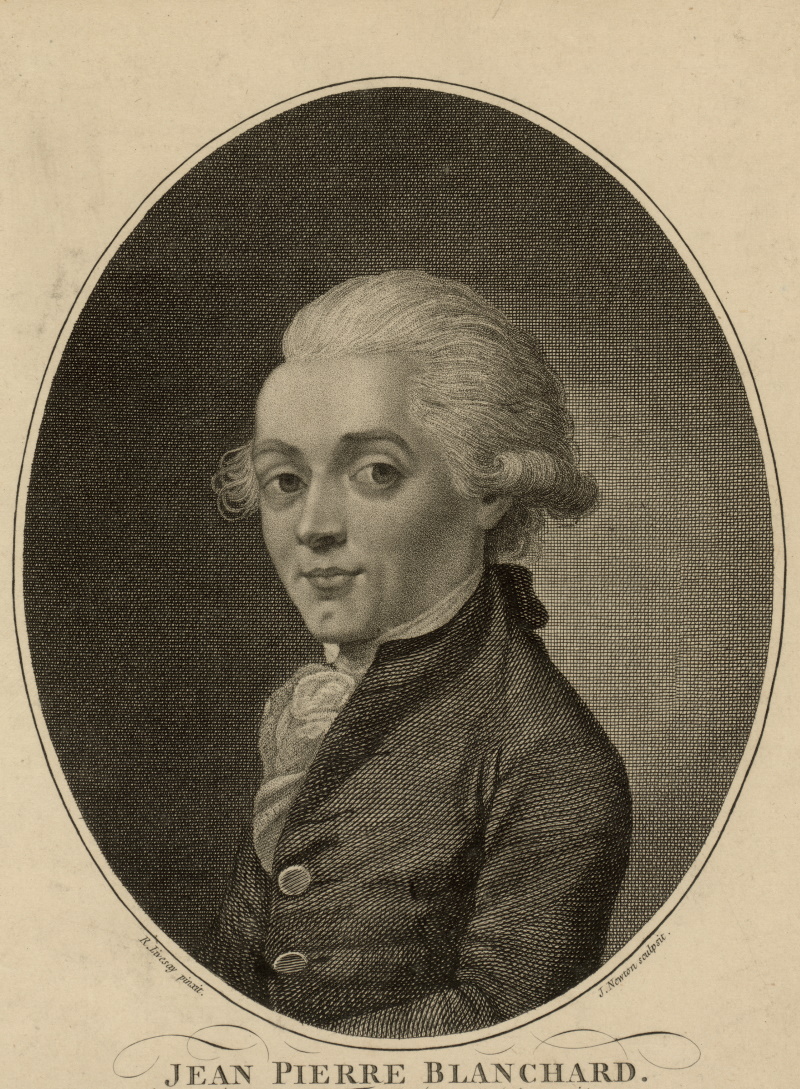

A large crowd gathered outside the walls of the Walnut Street Prison that fronted what is now Independence Square in Philadelphia at dawn on January 9, 1793. The occasion was not one public hanging but a balloon launching, which, if successful, would be the first aerial voyage in the history of the new United States of America and the New World. Jean-Pierre Blanchard, born on July 4, 1753, was a French inventor, best known as a pioneer of gas balloon flight, who distinguished himself in the conquest of the air in a balloon, in particular, the first crossing of the English Channel, on January 7, 1785. In December 1792, Blanchard had advertised, for weeks, in the Dunlap’s American Daily Advertiser that he would make a hydrogen-filled gas balloon ascension on January 9, 1793, at 1000 in the morning precisely.

So, on the morning of January 9, at 1000 past 1000 to be exact, Blanchard launched his balloon from the prison yard of Walnut Street Jail, and landed in successfully in Deptford, Gloucester County, New Jersey. One of the flight’s witnesses that day was President George Washington, and the future presidents’ John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe were also present. Blanchard wrote in his Journal: ‘I affixed to the aerostat my car, laden with ballast, meteorological instruments, and some refreshments with which the anxiety of my friends had provided me. I hastened to take leave of the President and of Mr. Ternant, Minister Plenipotentiary of France to the USA‘.

This is the way Blanchard used to describe the scene: ‘My ascent was perpendicular and so easy that I had even time to enjoy the different impressions which agitated so many sensible and interesting persons who surrounded the place of my departure and to salute them with my flag, which was ornamented on one side with the Armories bearings of the United States and, on the other, with the three colors so dear to the French nation’. On the ground, Gen John Steele, comptroller of the US Treasury, was astonished at what he saw. In a letter to a friend, he wrote: ‘seeing the man waving a flag at an immense height from the ground, was the most interesting sight that I ever beheld, and so I had no acquaintance with him, I could not help trembling for his safety’.

This is the way Blanchard used to describe the scene: ‘My ascent was perpendicular and so easy that I had even time to enjoy the different impressions which agitated so many sensible and interesting persons who surrounded the place of my departure and to salute them with my flag, which was ornamented on one side with the Armories bearings of the United States and, on the other, with the three colors so dear to the French nation’. On the ground, Gen John Steele, comptroller of the US Treasury, was astonished at what he saw. In a letter to a friend, he wrote: ‘seeing the man waving a flag at an immense height from the ground, was the most interesting sight that I ever beheld, and so I had no acquaintance with him, I could not help trembling for his safety’.

This may seem like a bit of an exaggeration, but the first real ‘paratrooper’ was a cute small little dog that Jean Pierre Blanchard placed inside a little basket. This was then attached to something they used to be called a ‘parachute’, then, the whole thing was dropped from the air balloon. The descent was slow enough to make sure that the animal survived. As seen in some old newspapers, when the dog and the basket smashed to the ground, the basket broke off, the dog ran away and no one saw him again.

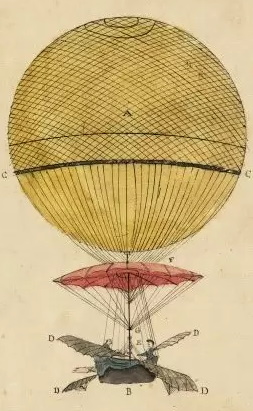

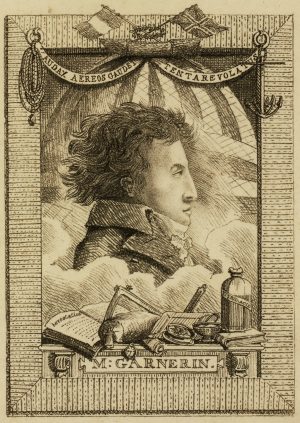

Born in Paris on January 31, 1769, André-Jacques Garnerin was a French balloonist and the inventor of the frameless parachute. Garnerin, a student of the ballooning pioneer professor Jacques Charles, was involved with the flight of hot air balloons and worked with his older brother Jean-Baptiste-Olivier Garnerin (1766–1849) in most of his ballooning activities and studied physics before joining the French Army. Over the next few years, Garnerin became interested in hot air balloons and advocated their use for military purposes. Appointed Official Aeronaut of France, he was captured by British troops during the first phase of the French Revolutionary Wars 1792–1797, turned over to the Austrians, and held as a prisoner of war in Buda in Hungary for three years.

Born in Paris on January 31, 1769, André-Jacques Garnerin was a French balloonist and the inventor of the frameless parachute. Garnerin, a student of the ballooning pioneer professor Jacques Charles, was involved with the flight of hot air balloons and worked with his older brother Jean-Baptiste-Olivier Garnerin (1766–1849) in most of his ballooning activities and studied physics before joining the French Army. Over the next few years, Garnerin became interested in hot air balloons and advocated their use for military purposes. Appointed Official Aeronaut of France, he was captured by British troops during the first phase of the French Revolutionary Wars 1792–1797, turned over to the Austrians, and held as a prisoner of war in Buda in Hungary for three years.

While he was a prisoner Garnerin began experimenting with parachutes. During his three-year stay, he never reached the stage where he could employ his parachute to escape from the high ramparts of the prison and had to wait until being released to continue experimenting when back in France. It was not until 1797 that Garnerin completed his first parachute. It consisted of a white silk canopy about 23 feet in diameter. The device had 36 ribs and lines, and was semi-rigid, making it look like a very large umbrella. Garnerin made finally his first successful parachute jump above Paris at the Plaine de Monceau, on October 22, 1797.

After ascending to an altitude of 3200 feet (975 M) in a hydrogen balloon Garnerin jumped from the basket, the parachute opened correctly but, oscillated wildly in the fall because of the lack of an air vent in the top of the canopy. A French Physicist, Jérôme-François de Lalande, who was present at the Plaine de Monceau, noticed the oscillations of the device used and proved that the problem was due to the lack of an Air Vent at the top of the canopy. Garnerin allowed de Lalande to modify his parachute and as it worked almost perfectly, he then decided to adopt the system.

After ascending to an altitude of 3200 feet (975 M) in a hydrogen balloon Garnerin jumped from the basket, the parachute opened correctly but, oscillated wildly in the fall because of the lack of an air vent in the top of the canopy. A French Physicist, Jérôme-François de Lalande, who was present at the Plaine de Monceau, noticed the oscillations of the device used and proved that the problem was due to the lack of an Air Vent at the top of the canopy. Garnerin allowed de Lalande to modify his parachute and as it worked almost perfectly, he then decided to adopt the system.

In 1799, Garnerin’s wife, Jeanne-Geneviève Labrosse, became the first woman to register a patent for the parachute as well as to be the first woman to make a parachute jump. Garnerin made exhibition jumps all over Europe including one of 8000 feet (2438 M) in England. It is to note that the initial use of the parachute was not saving a person who had to jump out from the basket of a hot air balloon but saving the entire device, balloon, basket, and the person.

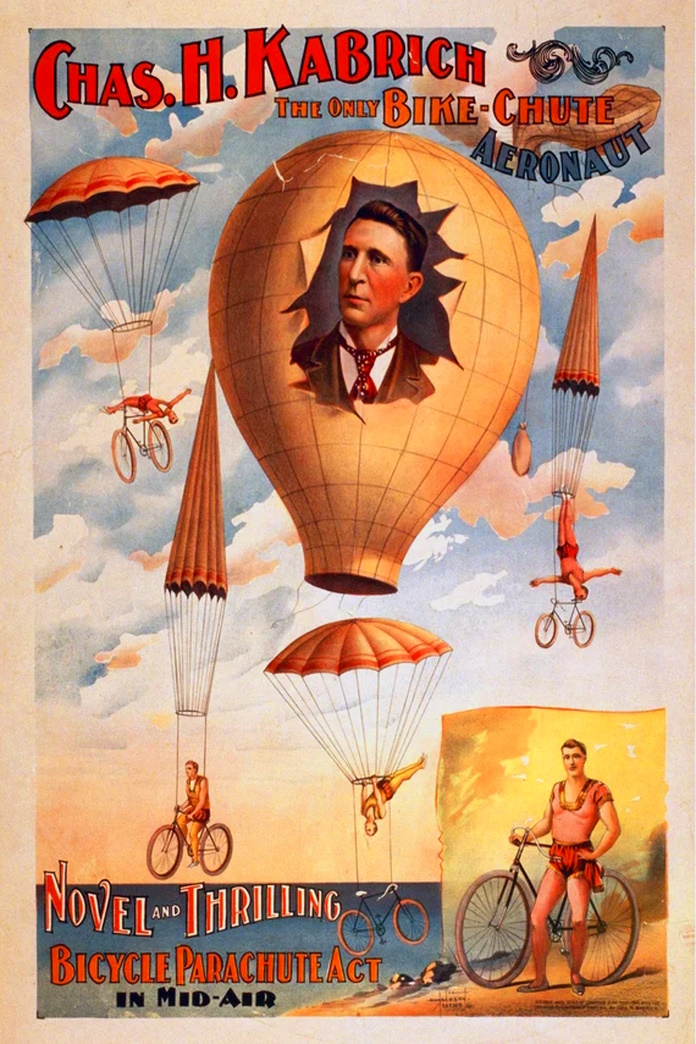

During the following century, parachute use was confined to carnivals and daredevil acts. Acrobats would perform stunts on a trapeze bar suspended from a descending parachute. The parachute was released from a hot-air balloon by attaching the top of the parachute to the equator of the balloon with a cord that broke after a person jumped from the basket.

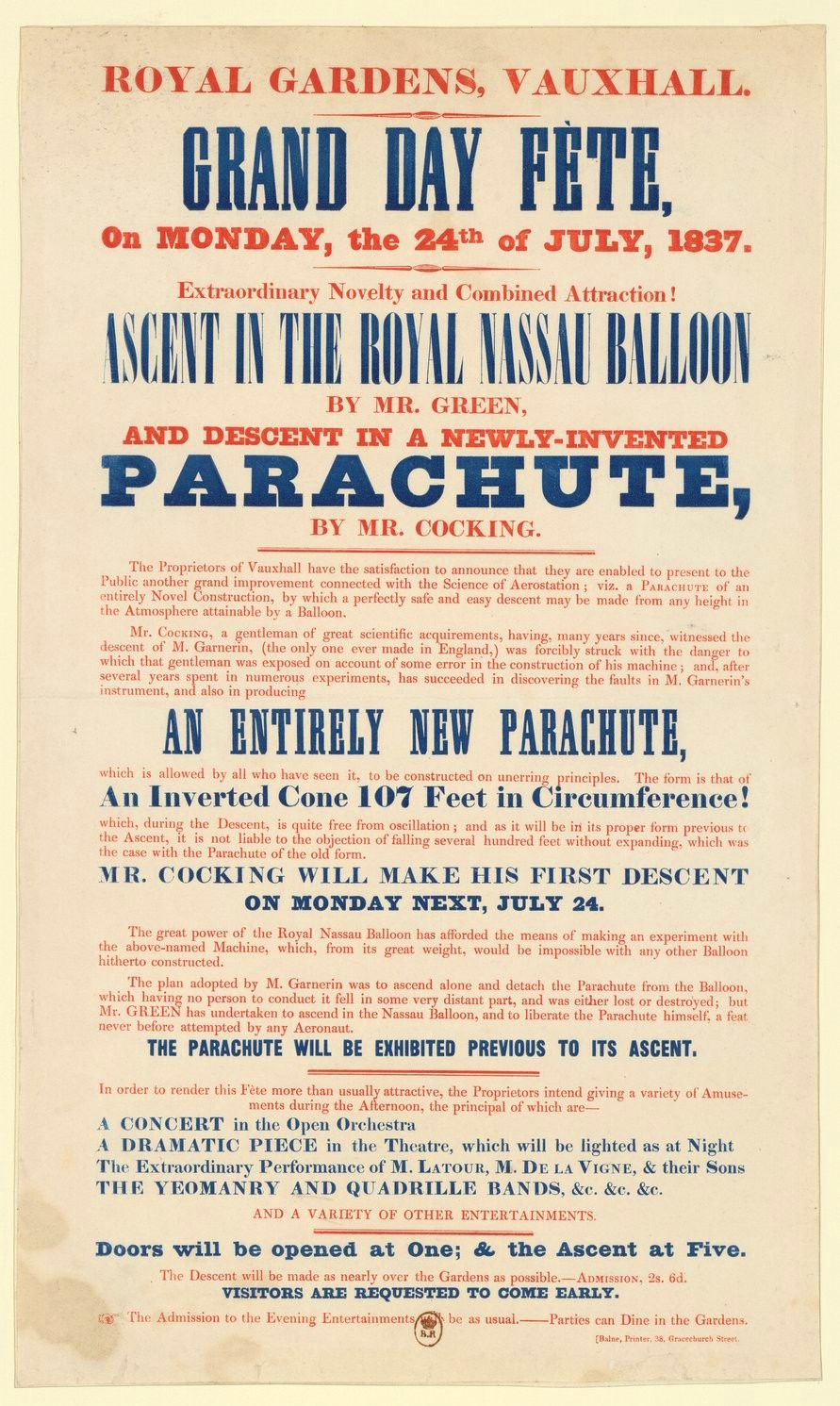

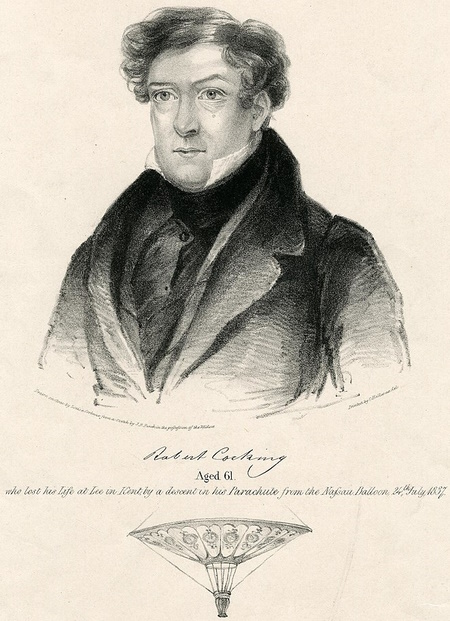

Public opinion became very unfavorable towards the use of parachutes when Robert Cocking, a professional watercolor artist with a keen amateur interest in science, who had seen André-Jacques Garnerin make the first parachute jump in England in 1802, fell to his death on July 24, 1837. Inspired to develop an improved design after reading Sir George Cayley, a man of independent means who had learned some science from a non-conformist clergyman who was also a fellow of the Royal Society, paper on ‘Aerial Navigation’, published in 1809–1810. Cocking, spent many years developing his improved parachute, based on Cayley’s design, which consisted of an inverted cone 107 feet (32,61 M) in circumference connected by three hoops. Cocking approached then Charles Green and Edward Spencer, owners of the balloon ‘Royal Nassau’ (formerly ‘Royal Vauxhall’), to allow him an opportunity to test his invention. Despite the fact that Cocking was already 61 years old, was not a professional scientist, and had no parachuting experience, the owners of the balloon agreed and advertised the event as the main attraction of a Grand Day Fete at the Vauxhall Gardens.

Public opinion became very unfavorable towards the use of parachutes when Robert Cocking, a professional watercolor artist with a keen amateur interest in science, who had seen André-Jacques Garnerin make the first parachute jump in England in 1802, fell to his death on July 24, 1837. Inspired to develop an improved design after reading Sir George Cayley, a man of independent means who had learned some science from a non-conformist clergyman who was also a fellow of the Royal Society, paper on ‘Aerial Navigation’, published in 1809–1810. Cocking, spent many years developing his improved parachute, based on Cayley’s design, which consisted of an inverted cone 107 feet (32,61 M) in circumference connected by three hoops. Cocking approached then Charles Green and Edward Spencer, owners of the balloon ‘Royal Nassau’ (formerly ‘Royal Vauxhall’), to allow him an opportunity to test his invention. Despite the fact that Cocking was already 61 years old, was not a professional scientist, and had no parachuting experience, the owners of the balloon agreed and advertised the event as the main attraction of a Grand Day Fete at the Vauxhall Gardens.

On July 24, 1837, at 0735, Cocking ascended hanging below the balloon, which was piloted by Green and Spencer. Cocking was in a basket that hung below the parachute which in turn hung below the basket of the balloon. Cocking had hoped to reach 8000 feet (2440 M), but the weight of the balloon coupled with that of the parachute and the three men slowed the ascent to 5000 feet (1500 M). With the balloon nearly over Greenwich, Green informed Cocking that he would be unable to rise any higher if the attempt was to be made in daylight. Faced with this information, Cocking released the parachute. A large crowd had gathered to witness the event, but it was immediately obvious that Cocking was in trouble. He had neglected to include the weight of the parachute itself in his calculations and as a result, the descent was far too quick. Though rapid, the descent continued evenly for a few seconds, but then the entire apparatus turned inside out and plunged downwards with increasing speed. The parachute broke up before it hit the ground and at about 200 to 300 feet (60 to 90 M) off the ground the basket detached from the remains of the canopy.

Cocking was killed instantly in the crash; his body was found in a field in Lee. The blame for the failure of the parachute was initially laid at Cayley’s door, but tests later revealed that although Cayley had neglected to mention the additional weight of the parachute in his paper, the cause of the crash had been a combination of the parachute’s weight and its flimsy construction, in particular the weak stitching connecting the fabric to the hoops. Cocking’s parachute weighed 250 lb (113 kg) many times more than modern parachutes. However, tests carried out in the USA by John Wise, an American balloonist, showed that Cocking’s design would have been successful if only it had been larger and better constructed.

Following the tragic death of Robert Cocking, parachuting became very unpopular and was confined to the carnival and circus acts until the late 19th century when developments such as harness and breakaway chutes made it safer.