#ww2, #history, #usmc, #paratroopers, @eucmh

Lt Col John T. Hoffman, US Marine Corps Reserve. Official Study – War Department, Silk Chutes and Hard Fighting, USMC Parachute Units in World War II, History and Museums Division, Headquarters USMC – Washington DC – 1999

Lt Col John T. Hoffman, US Marine Corps Reserve. Official Study – War Department, Silk Chutes and Hard Fighting, USMC Parachute Units in World War II, History and Museums Division, Headquarters USMC – Washington DC – 1999

Foreword

This historical pamphlet covers the Marine Corps’ flirtation with airborne operations during World War II. In tracing this story, I relied heavily on the relevant operational and administrative records of the Marine Corps held by the National Archives in Washington, DC, and College Park, Maryland, and the Washington National Records Center in Suitland, Maryland. The various offices of the Marine Corps Historical Center yielded additional primary materials. The Reference Section holds biographical data on most key individuals, as well as files on specific units. The Oral History Section has a number of pertinent interviews, the most significant being Gen Joseph C. Burger, Gen Marion L. Dawson, Gen Gerald C. Thomas, and Gen Robert H. Williams.

The Personal Papers Section has several collections pertaining to the parachute program. Among the most useful were the papers of Eldon C. Anderson, Eric Hammel, Nolen Marbrey, John C. McQueen, Peter Ortiz, and George R. Stallings. A number of secondary sources proved helpful. Marine Corps publications include Charles L. Updegraph’s US Marine Corps Special Units of World War II, Maj John L. Zimmerman’s Guadalcanal Campaign, Maj John N. Rentz’s Bougainville and the Northern Solomons, and Isolation of Rabaul by Henry I. Shaw, and Maj Douglas T. Kane. A valuable work on the overall American parachute program during the war is William B. Breuer’s Geronimo! The Marine Corps Gazette and Leatherneck contain a number of articles describing the parachute units and their campaigns. Ken Haney’s An Annotated Bibliography of USMC Paratroopers in World War II provides a detailed list of sources, including Haney’s extensive list of publications on the subject.

The Personal Papers Section has several collections pertaining to the parachute program. Among the most useful were the papers of Eldon C. Anderson, Eric Hammel, Nolen Marbrey, John C. McQueen, Peter Ortiz, and George R. Stallings. A number of secondary sources proved helpful. Marine Corps publications include Charles L. Updegraph’s US Marine Corps Special Units of World War II, Maj John L. Zimmerman’s Guadalcanal Campaign, Maj John N. Rentz’s Bougainville and the Northern Solomons, and Isolation of Rabaul by Henry I. Shaw, and Maj Douglas T. Kane. A valuable work on the overall American parachute program during the war is William B. Breuer’s Geronimo! The Marine Corps Gazette and Leatherneck contain a number of articles describing the parachute units and their campaigns. Ken Haney’s An Annotated Bibliography of USMC Paratroopers in World War II provides a detailed list of sources, including Haney’s extensive list of publications on the subject.

Many Marine parachutists graciously provided interviews, news clippings, photographs, and other sources for this work. Col Dave E. Severance, secretary-treasurer of the Association of Survivors, was especially obliging in culling material from his extensive files. I would like to thank Denis M. Frank, former Chief Historian for the History and Museums Division, for his insightful advice and editing. Many members of the division staff ably assisted the research and production effort: Charles D. Melson, Chief Historian; Jack Shulimson and Charles R. Smith of the Writing Section; Evelyn A. Englander of the Library; Amy C. Cantin of Personal Papers; Ann A. Ferrante, Danny J. Crawford, and Robert V. Aquilina of Reference Section; Richard A. Long and David B. Crist of Oral History; Lena M. Kaljot of the Photographic Section; Frederick J. Graboske and Joyce Conyers-Hudson of the Archives Section; and Robert E. Struder, W. Stephen Hill, and Catherine A. Kerns of Editing and Design.

Jon T. Hoffman

Lt Col, US Marine Corps Reserve

Silk Chutes and Hard Fighting: US Marine Corps Parachute Units in World War II is a brief narrative of the development, deployment, and eventual demise of Marine parachute units during World War II. It is published to honor the veterans of these special units and for the information of those interested in Marine parachutists and the events in which they participated. Lt Col Jon T. Hoffman, USMC (R), is an infantry officer currently on duty as a staff officer with the Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force Experimental. During his 15 years of active duty, he has served as a platoon and company commander with 2nd Battalion 3rd Marines; inspector-instructor with 2nd Battalion 23rd Marines; history instructor at the US Naval Academy, and action officer at Headquarters Marine Corps. His reserve service has been with the field history branch of the Marine Corps History and Museums Division, the II Marine Expeditionary Force Augmentation Command Element, and the adjunct faculty of the Marine Corps Command & Staff College. He is a distinguished graduate of the resident program of the latter institution. He also holds a bachelor’s degree from Miami University, a law degree from Duke University, and a master’s degree in military history from Ohio State University. His 1994 biography of Gen Merritt A. Edson, once A Legend, received the Marine Corps Historical Foundation’s Greene Award and was selected for the Commandant of the Marine Corps’ Reading List. His numerous articles in the professional military and historical journals have earned a dozen prizes, most notably the Marine Corps Historical Foundation’s Heinl Award for 1992, 1993, 1994, and 1995. In the interests of accuracy and objectivity, the History and Museums Division welcomes comments on this pamphlet from key participants, Marine Corps activities, and interested individuals.

Silk Chutes and Hard Fighting: US Marine Corps Parachute Units in World War II is a brief narrative of the development, deployment, and eventual demise of Marine parachute units during World War II. It is published to honor the veterans of these special units and for the information of those interested in Marine parachutists and the events in which they participated. Lt Col Jon T. Hoffman, USMC (R), is an infantry officer currently on duty as a staff officer with the Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force Experimental. During his 15 years of active duty, he has served as a platoon and company commander with 2nd Battalion 3rd Marines; inspector-instructor with 2nd Battalion 23rd Marines; history instructor at the US Naval Academy, and action officer at Headquarters Marine Corps. His reserve service has been with the field history branch of the Marine Corps History and Museums Division, the II Marine Expeditionary Force Augmentation Command Element, and the adjunct faculty of the Marine Corps Command & Staff College. He is a distinguished graduate of the resident program of the latter institution. He also holds a bachelor’s degree from Miami University, a law degree from Duke University, and a master’s degree in military history from Ohio State University. His 1994 biography of Gen Merritt A. Edson, once A Legend, received the Marine Corps Historical Foundation’s Greene Award and was selected for the Commandant of the Marine Corps’ Reading List. His numerous articles in the professional military and historical journals have earned a dozen prizes, most notably the Marine Corps Historical Foundation’s Heinl Award for 1992, 1993, 1994, and 1995. In the interests of accuracy and objectivity, the History and Museums Division welcomes comments on this pamphlet from key participants, Marine Corps activities, and interested individuals.

Michael E. Monigan, Col USMC

Director of Marine Corps History and Museums

Parachute Troops for Military Forces

After their first successful operation jump in Stavanger-Sola during the German Campaign of Norway, on Apr 9, 1940, the German Fallschirmjaeger spearheaded the German Army which had launched its offensive in Western Europe by crossing the borders of neutral Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg, Operation Fall Gelb (Plan Yellow). On May 10, 1940, by attacking through the Low Countries, the German Oberkommando der Wehrmacht believed that German forces could outflank the French Maginot Line and then advance through southern Belgium and northern France, cutting off the British Forces and a large number of French forces. This would force the French government to surrender.

To gain access to northern France, the invaders would have to defeat the armed forces of the Low Countries and either bypass or neutralize several defensive positions, primarily in Belgium and the Netherlands. Some of these defensive positions were only lightly defended and intended more as delaying positions than true defensive lines designed to stop an enemy attack. However, some defenses were of a more permanent nature and possessed even considerable fortifications garrisoned by significant numbers of troops. The Grebbe-Peel Line in the Netherlands, which stretched from the southern shore of the Zuiderzee to the Belgian Border near Weert, had a large number of fortifications combined with natural obstacles, such as marsh-lands and the Geld Valley, which could easily be flooded to impede an attack.

The main Belgian Defensive line, the Line KW, also known as the Dijl Line, along the Dyle River, protected the port of Antwerp and the Belgian Capital, Brussels. Between the KW Line and the border was a delaying line along the Albert Canal. This delaying line was protected by forwarding positions manned by troops, except in a single area where the canal ran close to the Dutch Border, which was known as the Maastricht Appendix due to the proximity of the Dutch City. There, the Belgian military could not build forward positions due to the proximity of the border, and instead assigned an infantry division to guard the three bridges over the canal in the area, a brigade being assigned to each bridge. The bridges were defended by blockhouses equipped with machine-guns. Artillery support was provided by the Fortress in Eben-Emael, whose artillery pieces covered two of the bridges. The German High Command became aware of the defensive plan, which called for Belgian forces to briefly hold the delaying positions along the Albert Canal and then retreat to link up with British and French forces on the KW Line. The Germans developed a strategy that would disrupt this plan, by seizing the three bridges in the Maastricht Appendix, as well as other bridges in Belgium and the Netherlands. This would allow their own forces to breach the defensive positions and advance into the Netherlands.

The main Belgian Defensive line, the Line KW, also known as the Dijl Line, along the Dyle River, protected the port of Antwerp and the Belgian Capital, Brussels. Between the KW Line and the border was a delaying line along the Albert Canal. This delaying line was protected by forwarding positions manned by troops, except in a single area where the canal ran close to the Dutch Border, which was known as the Maastricht Appendix due to the proximity of the Dutch City. There, the Belgian military could not build forward positions due to the proximity of the border, and instead assigned an infantry division to guard the three bridges over the canal in the area, a brigade being assigned to each bridge. The bridges were defended by blockhouses equipped with machine-guns. Artillery support was provided by the Fortress in Eben-Emael, whose artillery pieces covered two of the bridges. The German High Command became aware of the defensive plan, which called for Belgian forces to briefly hold the delaying positions along the Albert Canal and then retreat to link up with British and French forces on the KW Line. The Germans developed a strategy that would disrupt this plan, by seizing the three bridges in the Maastricht Appendix, as well as other bridges in Belgium and the Netherlands. This would allow their own forces to breach the defensive positions and advance into the Netherlands.

At 0530, on the morning of May 10, 1940, German Luftwaffe Junkers Ju 52/3m towing DFS-230 type gliders carrying the men of the Sturmabteilung Koch (Assault Detachment Koch) were en route to the Fort in Eben-Emael. A couple of minutes before H Hour, 9 of the 11 DFS-230 gliders who had left Germany earlier swooped out of the dark sky and landed on a patch of ground that covered the roof of Gigantic Armored Fortress, one of the key position in the Liège Belt Defenses (Ceinture de Fortifications de Liège) in Belgium, along the Albert Canal. This part of the Fortification Belt had 3 major Fortresses in the defenses line of the Belgian Army: the Fort d’Eben-Emael, the Fort de Battice and the Fort de Tancrémont.

At 0530, on the morning of May 10, 1940, German Luftwaffe Junkers Ju 52/3m towing DFS-230 type gliders carrying the men of the Sturmabteilung Koch (Assault Detachment Koch) were en route to the Fort in Eben-Emael. A couple of minutes before H Hour, 9 of the 11 DFS-230 gliders who had left Germany earlier swooped out of the dark sky and landed on a patch of ground that covered the roof of Gigantic Armored Fortress, one of the key position in the Liège Belt Defenses (Ceinture de Fortifications de Liège) in Belgium, along the Albert Canal. This part of the Fortification Belt had 3 major Fortresses in the defenses line of the Belgian Army: the Fort d’Eben-Emael, the Fort de Battice and the Fort de Tancrémont.

The 60-odd men of a parachute-engineer detachment quickly debarked and set about their well-rehearsed work. Using newly developed shaped charges, they systematically destroyed the armored cupolas housing the fort’s artillery pieces and machine guns. Although Eben Emael‘s 1200 defenders held out below ground for another 24 hours before surrendering, the fort had ceased to be a military obstacle.

The 60-odd men of a parachute-engineer detachment quickly debarked and set about their well-rehearsed work. Using newly developed shaped charges, they systematically destroyed the armored cupolas housing the fort’s artillery pieces and machine guns. Although Eben Emael‘s 1200 defenders held out below ground for another 24 hours before surrendering, the fort had ceased to be a military obstacle.

The paratroopers lost just six killed and 15 wounded. Simultaneously with this assault, a battalion of German parachute infantry seized two nearby bridges and prevented sentries from setting off demolition charges. These precursor operations allowed two Panzer Divisions to cross the Meuse River on May 11 and collapse Belgium‘s entire defensive line. Germany’s remaining five Fallschirmjaeger Battalions conducted similar missions in Holland and achieved substantial results. In the course of a few hours, 4500 Fallschirmjaeger had opened the road to an easy conquest of the Low Countries and laid the groundwork for Germany’s amazingly swift victory in the subsequent Battle of France. These stunning successes caused armed forces around the world to take stock of the role of parachutists in modern war.

The widely publicized airborne coup in the Low Countries created an immediate, high-level reaction within the Marine Corps. On May 14, the acting director of the Division of Plans and Policies at Headquarters Marine Corps issued a memorandum to his staff officers. The one-page document came right to the point in its first sentence: Gen Thomas Holcomb has ordered that we prepare plans for the employment of parachute troops. The matter was obviously of the highest priority since Col Pedro A. del Valle asked for immediate responses, which could be submitted in pencil on scrap paper. Perhaps as telling, the memorandum did not direct a mere study, but the creation of a course of action. Considering the Corps’ complete lack of expertise in this emerging field of warfare, HQs quickly translated staff plans into reality. The first small group of volunteers reported for training in October 1940 and graduated the following February. Succeeding classes went through an accelerated program for basic parachute qualification, but the numbers mounted very slowly.

The widely publicized airborne coup in the Low Countries created an immediate, high-level reaction within the Marine Corps. On May 14, the acting director of the Division of Plans and Policies at Headquarters Marine Corps issued a memorandum to his staff officers. The one-page document came right to the point in its first sentence: Gen Thomas Holcomb has ordered that we prepare plans for the employment of parachute troops. The matter was obviously of the highest priority since Col Pedro A. del Valle asked for immediate responses, which could be submitted in pencil on scrap paper. Perhaps as telling, the memorandum did not direct a mere study, but the creation of a course of action. Considering the Corps’ complete lack of expertise in this emerging field of warfare, HQs quickly translated staff plans into reality. The first small group of volunteers reported for training in October 1940 and graduated the following February. Succeeding classes went through an accelerated program for basic parachute qualification, but the numbers mounted very slowly.

MARINE PARACHUTE PIONEERS

In October 1940, the Commandant sent a circular letter to all units and posts to solicit volunteers for the paratroopers. All applicants, with the exception of officers above the rank of captain, had to meet a number of requirements regarding age: 21 to 32 years; height: 66 to 74 inches, and health: normal eyesight and blood pressure. In addition, they had to be unmarried, an indication of the expected hazards of the duty.

Applications were to include information on Marine’s educational record and athletic experience, so Headquarters was obviously interested in placing above-average individuals in these new units. The letter further stated that personnel qualified as paratrooper would receive an unspecified amount of extra pay. The money served as both a recognition of the danger and an incentive to volunteer. Congress would eventually set the additional monthly pay for parachutists at $100 for officers and $50 for enlisted men. Since a private first class at that time earned about $36 per month and a second lieutenant $125, the increase amounted to a hefty bonus. It would prove to be a significant factor in attracting volunteers, though parachuting would have generated a lot of interest without the money. As one early applicant later put it, based on common knowledge of the German success in the Low Countries, many Marines thought that this was going to be a grand and glorious business. Parachute duty promised plenty of action and the chance to get in on the ground floor of a revolutionary type of warfare.

Applications were to include information on Marine’s educational record and athletic experience, so Headquarters was obviously interested in placing above-average individuals in these new units. The letter further stated that personnel qualified as paratrooper would receive an unspecified amount of extra pay. The money served as both a recognition of the danger and an incentive to volunteer. Congress would eventually set the additional monthly pay for parachutists at $100 for officers and $50 for enlisted men. Since a private first class at that time earned about $36 per month and a second lieutenant $125, the increase amounted to a hefty bonus. It would prove to be a significant factor in attracting volunteers, though parachuting would have generated a lot of interest without the money. As one early applicant later put it, based on common knowledge of the German success in the Low Countries, many Marines thought that this was going to be a grand and glorious business. Parachute duty promised plenty of action and the chance to get in on the ground floor of a revolutionary type of warfare.

To get the program underway, the Commandant transferred Marine Capt Marion L. Dawson from duty with the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics to Lakehurst (New Jersey), to oversee the new school. Two enlisted Marine parachute riggers would serve as his initial assistants. Marine parachuting got off to an inauspicious start when Capt Dawson and two lieutenants made a visit to Hightstown (New Jersey), to check out the jumping towers (Safe Parachute Manufacturing Company). The other officers, Lt Walter S. Osipoff and Lt Robert C. McDonough were slated to head the Corps’ first group of parachute trainees. After watching a brief demonstration, the owner suggested that the Marines give it a test. As Dawson later recalled, he reluctantly agreed, only to break his leg when he landed at the end of his free fall.

On October 26, 1940, Osipoff, McDonough, and 38 enlisted men reported to Lakehurst. The Corps was still developing its training program, so the initial class spent 10 days at Hightstown starting on October 28. Immediately after that they joined a new class at the Parachute Material School and followed that 16-week course of instruction until its completion on February 27, 1941. A Douglas R3D-2 transport plane arrived from Quantico on December 6 and remained there through December 21, so the pioneer Marine paratroopers made their first jumps during this period. For the remainder of the course, they leap from Navy blimps stationed at Lakehurst. Lt Osipoff, the senior officer, had the honor of making the first jump by a Marine paratrooper. By graduation, each man had completed the requisite 10 jumps to qualify as a paratrooper and parachute rigger.

On October 26, 1940, Osipoff, McDonough, and 38 enlisted men reported to Lakehurst. The Corps was still developing its training program, so the initial class spent 10 days at Hightstown starting on October 28. Immediately after that they joined a new class at the Parachute Material School and followed that 16-week course of instruction until its completion on February 27, 1941. A Douglas R3D-2 transport plane arrived from Quantico on December 6 and remained there through December 21, so the pioneer Marine paratroopers made their first jumps during this period. For the remainder of the course, they leap from Navy blimps stationed at Lakehurst. Lt Osipoff, the senior officer, had the honor of making the first jump by a Marine paratrooper. By graduation, each man had completed the requisite 10 jumps to qualify as a paratrooper and parachute rigger.

Not all made it through. Several dropped from the program due to ineptitude or injury. The majority of these first graduates were destined to remain at Lakehurst as instructors or to serve the units in the Fleet Marine Force as riggers. By the time the second training class had been reported, Dawson and his growing staff had created a syllabus for the program. The first two weeks were ground school, which emphasized conditioning, wearing of the harness, landing techniques, dealing with wind drag of the parachute once on the ground, jumping from platforms and a plane mock-up, and packing chutes. Students spent the third week riding a bus each day to Hightstown where they applied their skills on the towers. The final two weeks consisted of work from aircraft and tactical training as time permitted.

Not all made it through. Several dropped from the program due to ineptitude or injury. The majority of these first graduates were destined to remain at Lakehurst as instructors or to serve the units in the Fleet Marine Force as riggers. By the time the second training class had been reported, Dawson and his growing staff had created a syllabus for the program. The first two weeks were ground school, which emphasized conditioning, wearing of the harness, landing techniques, dealing with wind drag of the parachute once on the ground, jumping from platforms and a plane mock-up, and packing chutes. Students spent the third week riding a bus each day to Hightstown where they applied their skills on the towers. The final two weeks consisted of work from aircraft and tactical training as time permitted.

Students had to complete six jumps to qualify as a paratrooper. The trainers had accumulated their knowledge from the Navy staff, from observing Army training at Fort Benning, and from a film depicting German paratroopers. The latter resulted in one significant Marine departure from US Army methods. Whereas the Army made a vertical exit from the aircraft, basically just stepping out the door, Marines copied the technique depicted in the German film and tried to make a near-perpendicular dive, somewhat like a swimmer coming off the starting block.

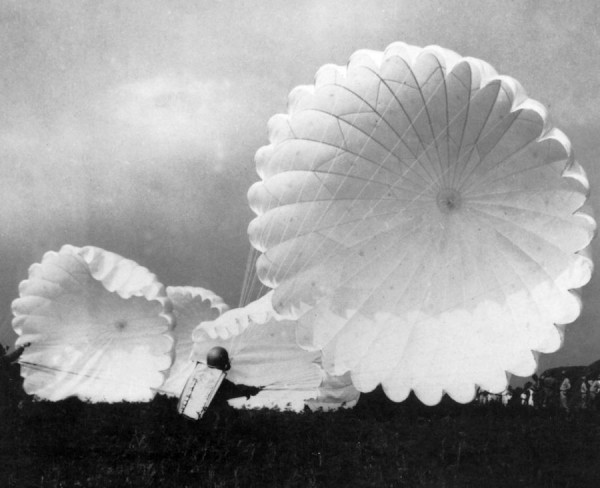

Marine paratroopers used two parachutes in training and in tactical jumps. They wore the main chute in a backpack configuration and a reserve chute on their chest. When jumping from transport planes, the main opened by means of a static line attached to a cable running lengthwise in the cargo compartment.