Document Source: (Note) Photos are for illustration purposes and all original. The original title of this archive is ‘From Forced Workers Camp to Yankee Division’, War Memories of Boleslaw Piatkowski. This archive, presented as a small booklet, was written down by Jacek Okon (Poland). The iconography is made of private photos from the author, Boleslaw Piatkowski, Internet images, photos archives from the European Center of Military History as well as photos from the James ‘Jim’ Haahr archives, a veteran of the Yankee Division (101st Infantry Regiment, 26th Infantry Division). It is with great pride that I bring attention to the Polish citizens who, liberated from the German Forced Labor Workers Camps, became part of the 26th Infantry Division and thus, helped the US Army to terminate the definitive liberation of Europa during the last months of the war in 1945.

(Doc Snafu: Final Check, September 12, 2022)

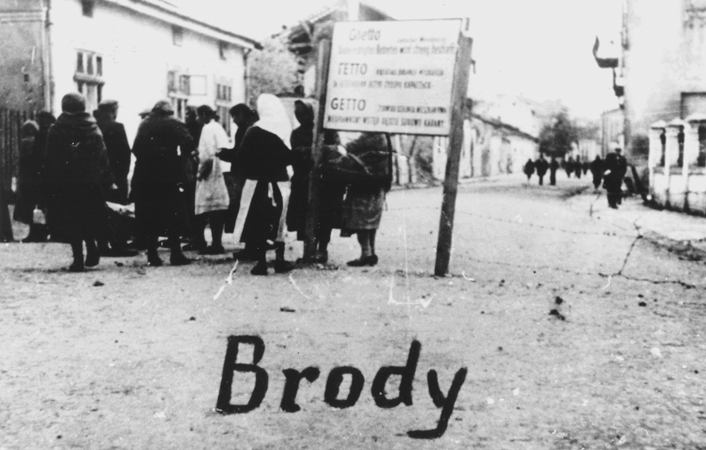

My name is Boleslaw Piatkowski. I am a Polish citizen and I was born on October 13, 1927, in the small district town of Brody in the Tarnopol Province which is located in the eastern part of Poland and belongs today to Ukraine. My Mother’s family name was Glogowska (i.e a daughter of Glogowski), and my Father Jan (John) Piatkowski was a Polish pre-war policeman. He died in 1985. I had two brothers, the older one was Kazimierz (Kazik), and the younger was Mieczyslaw (Mietek). I also had one sister, Maria. We all, including my parents, were of Polish origin. We lived in this small town in a four families house on Cicha Street 3, having the neighborhood consisting of two Polish families and one Jewish. The population in Brody, about 1100 people, was mainly composed of Jewish families, then Ukrainian families, and finally, Polish families (10%) totaling about 1096 inhabitants. The town was also garrisoned by the Nowogródzka Cavalry Brigade under the command of Gen Wladyslaw Anders who, in 1944, was in charge of the Polish Corps which raided the Abey in Monte Cassino in Italy. I knew his son who was my age and we were together in school.

My name is Boleslaw Piatkowski. I am a Polish citizen and I was born on October 13, 1927, in the small district town of Brody in the Tarnopol Province which is located in the eastern part of Poland and belongs today to Ukraine. My Mother’s family name was Glogowska (i.e a daughter of Glogowski), and my Father Jan (John) Piatkowski was a Polish pre-war policeman. He died in 1985. I had two brothers, the older one was Kazimierz (Kazik), and the younger was Mieczyslaw (Mietek). I also had one sister, Maria. We all, including my parents, were of Polish origin. We lived in this small town in a four families house on Cicha Street 3, having the neighborhood consisting of two Polish families and one Jewish. The population in Brody, about 1100 people, was mainly composed of Jewish families, then Ukrainian families, and finally, Polish families (10%) totaling about 1096 inhabitants. The town was also garrisoned by the Nowogródzka Cavalry Brigade under the command of Gen Wladyslaw Anders who, in 1944, was in charge of the Polish Corps which raided the Abey in Monte Cassino in Italy. I knew his son who was my age and we were together in school.

When my father retired in February 1939, the very day Pope Pius XI passed, our family moved westward to the small town of Ostrowek, along the Vistula River, in the vicinity of the town of Mielec. My father hoped to find a job at the National Aircraft Factory in Mielec, but he failed in it. First, the entire family lived in a single rented room. In 1941, we took possession by inheritance of a village house covered with a thatched roof and a pugging floor. This house was still in the family’s possession and used by my sister Maria, as long as 1997 when it collapsed. The town of Ostrowek had something like a natural fortress because it was located in the center of a triangle made of the Vistula River, the Wiskola River, and the Bern River. The west part of the town was protected by the large Vistula, the northern part of the town all along up to the east by the Wiskola, and the southern part of the village by the Bern. Considering often rivers overflow, there were ground dams heaped up from four sides between the village and the rivers. Visitors usually said that these dams were like ramparts, and I do even believe that the literal translation of Ostrawek gives out Little Island, which can say much more about the location of this human habitation.

When my father retired in February 1939, the very day Pope Pius XI passed, our family moved westward to the small town of Ostrowek, along the Vistula River, in the vicinity of the town of Mielec. My father hoped to find a job at the National Aircraft Factory in Mielec, but he failed in it. First, the entire family lived in a single rented room. In 1941, we took possession by inheritance of a village house covered with a thatched roof and a pugging floor. This house was still in the family’s possession and used by my sister Maria, as long as 1997 when it collapsed. The town of Ostrowek had something like a natural fortress because it was located in the center of a triangle made of the Vistula River, the Wiskola River, and the Bern River. The west part of the town was protected by the large Vistula, the northern part of the town all along up to the east by the Wiskola, and the southern part of the village by the Bern. Considering often rivers overflow, there were ground dams heaped up from four sides between the village and the rivers. Visitors usually said that these dams were like ramparts, and I do even believe that the literal translation of Ostrawek gives out Little Island, which can say much more about the location of this human habitation.

But war is war and even the best-hidden village cannot avoid being included in a battlefield. We lived in a constant threat, not knowing the day and the hour. Although in November 1942, when the war in the shape of the German Feldgendarme (Field Police) had violently knocked at our house’s doors, no one in our family was a ‘forest boy’, still the consciousness of the danger was with us long before. Under our thatched roof, on our pugging floor, in our great room, partisans were coming together, considering that it was the safest house of all the villager’s cottages. Father was bringing secret news sheets along and was considered by partisans as one of them. It didn’t take a long time for my father to become staunched, and our house became the main contact point in Ostrowski. This partisan unit was named Jedrusie and was united with the AK (Home Army) which was led by Polish Emigrated Government in London. Later, as well, my older brother Kazimierz left home and went into this unit as a soldier. But it was later when I was in a lager in Germany.

But war is war and even the best-hidden village cannot avoid being included in a battlefield. We lived in a constant threat, not knowing the day and the hour. Although in November 1942, when the war in the shape of the German Feldgendarme (Field Police) had violently knocked at our house’s doors, no one in our family was a ‘forest boy’, still the consciousness of the danger was with us long before. Under our thatched roof, on our pugging floor, in our great room, partisans were coming together, considering that it was the safest house of all the villager’s cottages. Father was bringing secret news sheets along and was considered by partisans as one of them. It didn’t take a long time for my father to become staunched, and our house became the main contact point in Ostrowski. This partisan unit was named Jedrusie and was united with the AK (Home Army) which was led by Polish Emigrated Government in London. Later, as well, my older brother Kazimierz left home and went into this unit as a soldier. But it was later when I was in a lager in Germany.

Taken away from the Family Home

This happened in November 1942. I cannot remember the exact date of the month, but it was November 1942 and I was a 15 years old boy. The German Feldgendarmes didn’t, of course, foretell their visit. Somebody had warned my father and, in no time, the whole family, (father, mother, brothers, sister, and two little cousins) had left the house to find shelter over the dams. In the hurry, they had simply forgotten about me and, unaware of the threat, I was lying in bed with a bad cold and didn’t want to get up and escape. A little while later, when the Feldgendarmes were in the area checking all the houses, it was too late for me to escape. It appeared that they were searching for my elder brother Kazik, who was 17, as he had been designated by the Germans to be a forced worker for the III Reich. So they found me and there was nothing I could do or say. I knew that Kazik was hiding with the family over the dams and I wasn’t ready to tell the Germans that my name was Boleslaw (Boles) and not Kazik. They were searching for a 17 years old young boy called Piatkowski, I was one a Piatkowski, I was 15 years old but looked like 17 and I didn’t sure want to disabuse them. A couple of minutes later I was dragged out, identified as Kazik Piatkowski, and loaded in a truck heading soon for the town of Mielec. There were several men inside the truck. Sitting silently on wooden crates because we weren’t allowed to talk to each other. Besides this, there wasn’t a lot to say in such a situation.

I was feeling like Simon, the Cyrenian, when he was forced to bear the cross after Jesus couldn’t not more do it – but this was indeed the very best doing of his entire life. I am even certain about this. For us, in this truck, the only thing to do was to use the first opportunity to jump out and run away. When my parents returned home, they could not find me, and the neighbors explained to them what had happened to me. From our village, 5 persons were taken and loaded into the truck: Czeslawa (Czechia) Tworkowa, Myjak (I don’t remember his first name), brothers Ciejka (Edward – Edek) and Stanislaw (Staszek), and myself. My brother Kazik survived in such a happy way that before soon he joined the partisan unit Jedrusie and spent the left years of World War Two as a soldier, in the woods, and in battles. The truck we were in didn’t stop until being parked before the Low Court building in the center of Mielec. The Feldgendarmes screamed at us Raus, Schnell, and Schnell, and we were taken to an office upstairs. We didn’t know where we were conducted, but one of us, Edek Ciejka, wasn’t interested to know. With a fast movement, he passed me the grub (prog), which he has had from his mother for the way (I thought that I must have taken it only for a while, that perhaps he would lace up his shoes). But at this same moment, I heard his whisper: I run away boys! I had no time to ask him, how and when he would have to do it, and I became the witness of his escape. He switched around, in a few leaps jumped downstairs, and left the building by the main entrance. It was also the last time I saw him in my life.

I was feeling like Simon, the Cyrenian, when he was forced to bear the cross after Jesus couldn’t not more do it – but this was indeed the very best doing of his entire life. I am even certain about this. For us, in this truck, the only thing to do was to use the first opportunity to jump out and run away. When my parents returned home, they could not find me, and the neighbors explained to them what had happened to me. From our village, 5 persons were taken and loaded into the truck: Czeslawa (Czechia) Tworkowa, Myjak (I don’t remember his first name), brothers Ciejka (Edward – Edek) and Stanislaw (Staszek), and myself. My brother Kazik survived in such a happy way that before soon he joined the partisan unit Jedrusie and spent the left years of World War Two as a soldier, in the woods, and in battles. The truck we were in didn’t stop until being parked before the Low Court building in the center of Mielec. The Feldgendarmes screamed at us Raus, Schnell, and Schnell, and we were taken to an office upstairs. We didn’t know where we were conducted, but one of us, Edek Ciejka, wasn’t interested to know. With a fast movement, he passed me the grub (prog), which he has had from his mother for the way (I thought that I must have taken it only for a while, that perhaps he would lace up his shoes). But at this same moment, I heard his whisper: I run away boys! I had no time to ask him, how and when he would have to do it, and I became the witness of his escape. He switched around, in a few leaps jumped downstairs, and left the building by the main entrance. It was also the last time I saw him in my life.

Of course, the Feldgendarmes ran out on the double after him, but they didn’t catch him. He had executed a very brave and successful escape and was free again. I learned later, after the war, that Edek, unable to get back to the village, headed for the forest area and joined the Partisans with whom he was killed during a battle in 1944. Anyway, we were really happy because standing upstairs, the only thing important to us was the fact that Edek escaped from the Germans and ran away while we were still trying to find out a way to escape, more occupied analyzing our situation and drawing some plans in our minds.

Of course, the Feldgendarmes ran out on the double after him, but they didn’t catch him. He had executed a very brave and successful escape and was free again. I learned later, after the war, that Edek, unable to get back to the village, headed for the forest area and joined the Partisans with whom he was killed during a battle in 1944. Anyway, we were really happy because standing upstairs, the only thing important to us was the fact that Edek escaped from the Germans and ran away while we were still trying to find out a way to escape, more occupied analyzing our situation and drawing some plans in our minds.

Czechia Tworkorwa was led in a women’s cell, Myjak, Staszek Ciejka, and myself in a room upstairs. Doors were closed behind and we stayed there for three days. On the third day, we were loaded into one cattle truck at the railway station and taken to the prison in Debica where we stayed for a week. The next stage of this travel to the unknown (because we didn’t know where we would be sent) was the famous city of Krakow. From Debica to Krakow, we were poured inside a third-class railroad carriage. A short moment later, Czechia opened the window of the compartment, climbed on the seat, and leaned out of the small window holding on to the metallic frame. Then she jumped. She turned somersaults a little, stand up, and started running up to the woods. We all had seen it. The three of us didn’t have enough time to follow her as well as the German guard failed to hold her back. Anyway, Czechia was free and the train wasn’t stopped for this reason.

In Krakow, we spent the an entire week in prison’s cell, still unconscious of our future. Even today, I still did not find out in what street we were nor in what building we had been imprisoned. I had never been to this city before and I couldn’t find that location. Even after the war, I was several times in Krakow but the city is so large that I had to give out my research. Myjak was liberated in Krakow because he was the only one to work in his family and was, moreover, a shoemaker. He also had an illness (he had been referred to in vain in Mielec and Debica). In Krakow, somebody must have had some pity for him, and, thanks to the Lord, Myjak was sent back home. Now, there were only two left in our group, Staszek Ciejka and myself, both kids and both 15 years old. A couple of days later, another third-class railroad car in which we had been poured in with hundreds of other forced workers left Krakow. In this huge group, we were the youngest ones but our childhood was left behind us in Ostrowek.

In Krakow, we spent the an entire week in prison’s cell, still unconscious of our future. Even today, I still did not find out in what street we were nor in what building we had been imprisoned. I had never been to this city before and I couldn’t find that location. Even after the war, I was several times in Krakow but the city is so large that I had to give out my research. Myjak was liberated in Krakow because he was the only one to work in his family and was, moreover, a shoemaker. He also had an illness (he had been referred to in vain in Mielec and Debica). In Krakow, somebody must have had some pity for him, and, thanks to the Lord, Myjak was sent back home. Now, there were only two left in our group, Staszek Ciejka and myself, both kids and both 15 years old. A couple of days later, another third-class railroad car in which we had been poured in with hundreds of other forced workers left Krakow. In this huge group, we were the youngest ones but our childhood was left behind us in Ostrowek.

Forced Labor Camp Kahl am Main

After a long train ride, our next location was the Transition Camp in Chemnitz. The Camp staff was composed of Ukrainians. A young Ukrainian woman who during the basic medical check was writing down our data, raised her eyes, having heard the name ‘Piatkowski’. She was looking at me for a while in a strange way and asked using her Ukrainian language are you the brother of Maria Piatkowski from Brody?. I answered truthfully yes! She didn’t say anymore but I’ve noticed that from this moment to the end of our short stay in Chemnitz she’s avoided me as if she was afraid of something. I don’t know from where she knew my sister.

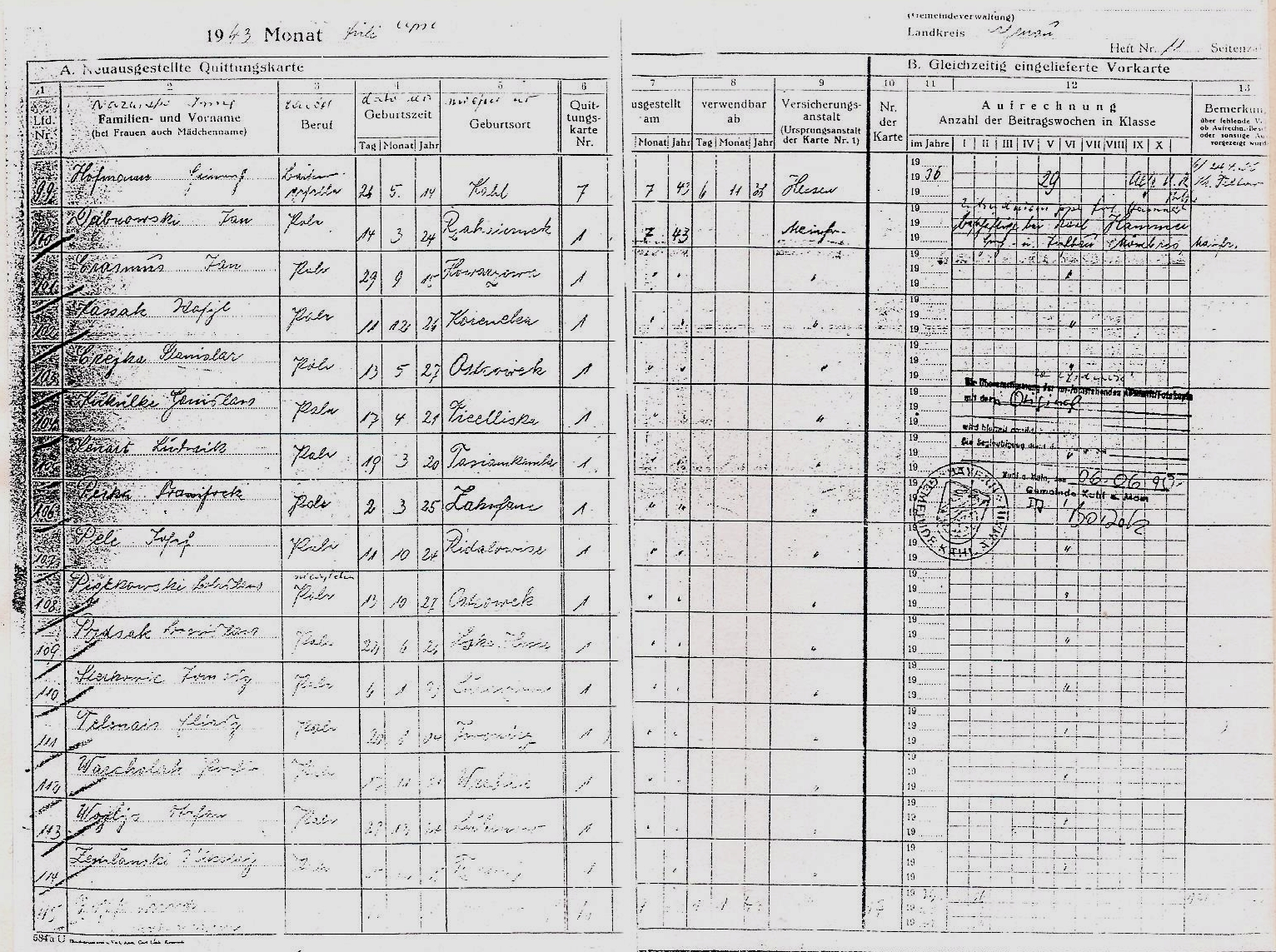

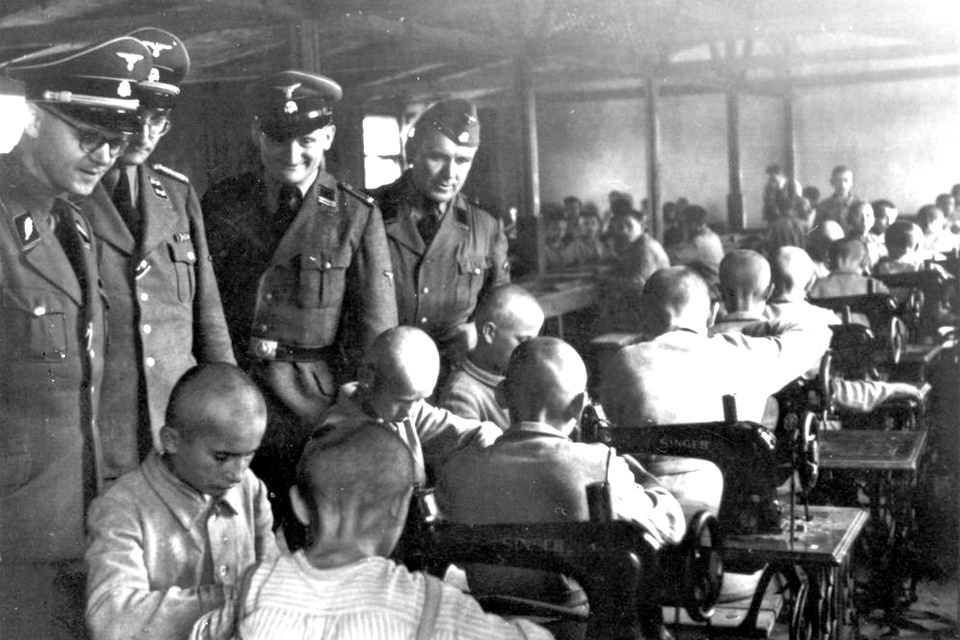

From the Camp in Chemnitz, we were taken to another Camp in Aschaffenburg where the selection was done and we were assigned a work camp or a workplace. Staszek Cejka was assigned with me to the Workers Camp in Kahl am Main. This was the first and only consolation for us, we would stay together. Kahl am Main proved to be a small town kept clean and tidy despite the war. But I didn’t have many occasions to have a look at the town as all my notices were limited to the ones I could see while working. All I saw and remember today are many gardens which were encircled by even large buildings. The camp I was sent to was the branch of the Schölkrippen-Lager (Schölkrippen was the abode of the concern of Hammer, for the benefit of which we formally worked). The camp was seated on the edges of the town nearby of a narrow-gauge railway station from where we went to work by train. The Main Railway Station, much bigger, was located downtown. The camp Kahl am Main contained hundreds of forced workers, Poles in the greater part, but there were also Ukrainians from the eastern part of pre-war Poland. We all but a few were young people and most of us weren’t yet more than twenty years old. Again, I was the youngest one.

We lived in wooden barracks, twenty men in each of them. Beds of boards for sleeping weren’t like these of present days, they were knocked together out of severe planks – it was our bad after all-day work. With time, when we knew more about the camp, we brought along from the rubbish heap the shavings, which were evicted by workers of the neighboring factory so we could sleep on these shavings, and replace them, because of fleas, which infested such mattresses. There were also lice and bed bugs, and after time went forward, we all had the itch. As the food we had, turnip-rooted cabbages (rutabaga), sugar beets, carrots, bruised grains, and rotten frozen potatoes; on holiday, we had a horse’s head.

We lived in wooden barracks, twenty men in each of them. Beds of boards for sleeping weren’t like these of present days, they were knocked together out of severe planks – it was our bad after all-day work. With time, when we knew more about the camp, we brought along from the rubbish heap the shavings, which were evicted by workers of the neighboring factory so we could sleep on these shavings, and replace them, because of fleas, which infested such mattresses. There were also lice and bed bugs, and after time went forward, we all had the itch. As the food we had, turnip-rooted cabbages (rutabaga), sugar beets, carrots, bruised grains, and rotten frozen potatoes; on holiday, we had a horse’s head.

Such were the components, which the German-cook woman Helena Friedrich could get for us from the camp administration. She was a good kind-hearted woman. We didn’t complain about her because, thanks to her, we could eat sometimes sweet cookies, which she was cooking at her home and brought to the camp. Sometimes she gave us her ration cards. When we worked along the tracks, we often could find a piece of bread packed in paper. The unknown greathearted German threw it down by a lavatory pan, being afraid of doing it publicly. I remember rare events when we were beaten by jailers, but it wasn’t often. Those jailers were disabled soldiers from the Poland Campaign in 1939 and the Low Countries and France Campaign in 1940. They were lesser proficient than we were.

We came to the camp in Kahl am Main during the wintertime. They didn’t give us any winter clothes and all we had was the clothes we had on the day of our capture. Sometimes, a native German had put on clothes stealthily, but those impulses of good hearts could not protect all of us against this and the next winter. Usually, our work as slaves consisted in digging ditches and laying electric cables in them. At daybreak, we took the train and went near Aschaffenburg. The cables had to run underground, so we had first to remove the snow and dig never-ending ditches, while the frozen ground was hard like a stone. We then laid down a new cable in the ditch and covered it with rubles, mostly stones, and earth. We were neither political prisoners nor prisoners of war. We were just forced workers, and because of this, due to wages. Elders than myself were receiving theirs. I never received my wage because – as one told me in the administration – I was too young.

We came to the camp in Kahl am Main during the wintertime. They didn’t give us any winter clothes and all we had was the clothes we had on the day of our capture. Sometimes, a native German had put on clothes stealthily, but those impulses of good hearts could not protect all of us against this and the next winter. Usually, our work as slaves consisted in digging ditches and laying electric cables in them. At daybreak, we took the train and went near Aschaffenburg. The cables had to run underground, so we had first to remove the snow and dig never-ending ditches, while the frozen ground was hard like a stone. We then laid down a new cable in the ditch and covered it with rubles, mostly stones, and earth. We were neither political prisoners nor prisoners of war. We were just forced workers, and because of this, due to wages. Elders than myself were receiving theirs. I never received my wage because – as one told me in the administration – I was too young.

Staszek Cejka and I stayed together all the time we spent in the lager at Kahl am Main. A third man, Franek Peska, a mountaineer from Zakopane, became a close friend to us. When Franek was sent to our camp he was 22 years old. His mountaineer dialect made him liked, and he was a first-rate comrade for both of us. He knew German and during our lunches, he often entered into conversation with Helena Friedrich, the cook-woman. She must have liked him too, because, in the beginning, he was the only one of us who was getting cookies and ration cards. This woman knew how to improve my wrestling with adversity. Franek told to Helena that I was not only the youngest one in the camp but also the most hard-working. After this recommendation she went to the foreman and extorted him to allow me, during my free time, to go work in her garden. I was very grateful to Franek for this because this additional work, the work after hours, consisted of weeding, watering, lopping a hedge and other gardener acting.

After hard manual labor, such relations with nature were like a true rest beside that each time, I was returning to the camp with a bag fulfilled with food and cigarettes (this was the beginning of my smoking for 25 years) and clothes. The fair division was taking place in our barracks. I owed such an abundance of goods to Helena’s daughter, Florentina. Florentina planned to become a hairdresser after the war and she exercised dressing on my hair. So by the occasion, my hair was done and I was scented with Eau de Cologne. (Since the end of the war I am exchanging letters with Florentina. She keeps inviting me to Kahl am Main but unfortunately, I wasn’t able to visit her. She came once to Poland to visit me and this was a very moving moment). Helena didn’t last long to advertise my abilities in garden works to Hilma, one of her relatives, and so I had work in two gardens followed soon by a third one owned by the widow of a Wehrmacht soldier who had been killed somewhere in the eastern front.

The wardrobes in her house were full of the clothes left by her husband. So, she ordered me to try on it, and if something suited me she gave it to me while saying let it stay not squandered. Wartime slave work consisted usually in digging ditches and putting down electric cables in Kahl am Main and in the immediate surroundings. In 1943, we became witnesses of the Allied bombardments. I think that they were quite new events for the inhabitants of the little town. Bombardments became more intense from month to month and it was the reason why our work changed from cable laying to rubbles clearing. We soon became intended for clearing the devastation, especially for returning snapped tracks to their place. We cut bent rails into pieces with blowpipes, without any gloves and goggles of course.

Usually, we were brought to work by train and we stayed there until the job has been finished even, when in sometime, it lasted a few days. When this happened we were told to sleep inside the railroad carriages. With the intensification of the bombardment, especially when bombings became a daily duty for the Allies, we were shifted from place to place. Accordingly, we were sent to Frankfurt, Hanau, Aschaffenburg, Offenbach, Fulda and Darmstadt. Bombs were causing tremendous damage. American bombers during the daytime and English during the night. Railroad tracks that were repaired after an American bombardment were often demolished by British bombers a few hours later. Usually, Bomber Groups consisted of 60 bombers who dropped their bombs at the same time on a target. We were impressed by phosphorus and incendiary bombs. Sometimes you could think that the sky and the ground were burning together. When an air raid caught us at work or asleep, we were hiding under the trains standing on the side tracks because the Germans did not allow us to use the air-raid shelters. Under the trains was the only way for us to find some protection. Sometimes, on their way back from a bombing mission, the British bombers were dropping false German rations-cards. Before the Germans could leave their air-raid shelters, we had sufficient time to pick up some of the paper bombs. Later, being in other towns, we went with these cards to the shop. I think that the work of these British falsifiers was excellent because no shopkeepers discovered the falsification. Air raids frightened us many times. But this fear was strictly connected with joy that the end of the war was at hand. And the sight, when the Germans were taking flight, engendered in us great satisfaction.

Usually, we were brought to work by train and we stayed there until the job has been finished even, when in sometime, it lasted a few days. When this happened we were told to sleep inside the railroad carriages. With the intensification of the bombardment, especially when bombings became a daily duty for the Allies, we were shifted from place to place. Accordingly, we were sent to Frankfurt, Hanau, Aschaffenburg, Offenbach, Fulda and Darmstadt. Bombs were causing tremendous damage. American bombers during the daytime and English during the night. Railroad tracks that were repaired after an American bombardment were often demolished by British bombers a few hours later. Usually, Bomber Groups consisted of 60 bombers who dropped their bombs at the same time on a target. We were impressed by phosphorus and incendiary bombs. Sometimes you could think that the sky and the ground were burning together. When an air raid caught us at work or asleep, we were hiding under the trains standing on the side tracks because the Germans did not allow us to use the air-raid shelters. Under the trains was the only way for us to find some protection. Sometimes, on their way back from a bombing mission, the British bombers were dropping false German rations-cards. Before the Germans could leave their air-raid shelters, we had sufficient time to pick up some of the paper bombs. Later, being in other towns, we went with these cards to the shop. I think that the work of these British falsifiers was excellent because no shopkeepers discovered the falsification. Air raids frightened us many times. But this fear was strictly connected with joy that the end of the war was at hand. And the sight, when the Germans were taking flight, engendered in us great satisfaction.

There was no humility in the Germans. It even seemed to me that their hatred of Allies even increased. Once upon a time, the German Flak shot down an already wounded British bomber that was flying too low. The plane crashed a few meters away from us and we saw that the body of the dead pilot had been thrown out of the wreck. German civilians came to see what happened and started immediately bullying the dead body with horrific obstinacy. They were spitting at him, throwing stones at him, Kicking, striking him with sticks, abusing him. As if they still believed that after that the victory could be with them. With the end of the winter, in 1945, we heard rifles shooting nearby, ticking with every hour. This time, it was not a thud of artillery from the distant front line, but quite close noise of combat. We were in our barracks at Kahl am Main. For a few days, we were not anymore taken to our daily work, and no one of us knew that the Camp was about to be evacuated. After a short skirmish in our near area, American units of the Third Army entered the town. When the jeep of the outpost had stopped in front of the Camp’s gates, our guard cripples came out to them with a white flag, holding hands up. Seeing the Germans guards with a white flag in their hand and walking to the gates of the Camp was an annoying sight. So, Staszek Ciejka, me, and Franek Peksa came out of our block and walked to the entrance of the Camp. There, we were looking at the first American soldiers with great admiration. For me, at this moment, they were so much magnificent as were our Polish Uhlans (Cavalrymen) I saw in the barrack in my native town of Brody. Of course, during my entire childhood, I was dreaming to become an Uhlan. The American soldiers gave us cans full of meat, cigarettes with filters, and chewing gums which for us was quite exotic.

There was no humility in the Germans. It even seemed to me that their hatred of Allies even increased. Once upon a time, the German Flak shot down an already wounded British bomber that was flying too low. The plane crashed a few meters away from us and we saw that the body of the dead pilot had been thrown out of the wreck. German civilians came to see what happened and started immediately bullying the dead body with horrific obstinacy. They were spitting at him, throwing stones at him, Kicking, striking him with sticks, abusing him. As if they still believed that after that the victory could be with them. With the end of the winter, in 1945, we heard rifles shooting nearby, ticking with every hour. This time, it was not a thud of artillery from the distant front line, but quite close noise of combat. We were in our barracks at Kahl am Main. For a few days, we were not anymore taken to our daily work, and no one of us knew that the Camp was about to be evacuated. After a short skirmish in our near area, American units of the Third Army entered the town. When the jeep of the outpost had stopped in front of the Camp’s gates, our guard cripples came out to them with a white flag, holding hands up. Seeing the Germans guards with a white flag in their hand and walking to the gates of the Camp was an annoying sight. So, Staszek Ciejka, me, and Franek Peksa came out of our block and walked to the entrance of the Camp. There, we were looking at the first American soldiers with great admiration. For me, at this moment, they were so much magnificent as were our Polish Uhlans (Cavalrymen) I saw in the barrack in my native town of Brody. Of course, during my entire childhood, I was dreaming to become an Uhlan. The American soldiers gave us cans full of meat, cigarettes with filters, and chewing gums which for us was quite exotic.

They told us that we were now liberated and that we were free. The gates were now wide open.

They told us that we were now liberated and that we were free. The gates were now wide open.

In the Yankee Division

Because there were no German guards anymore we could leave the Camp without any obstacles. So, after having had a meal from the American cans, we bade our comrade’s prisoners farewell and we went out into the town. There were still three of us, but our trio had varied: Staszek Ciejka having disappeared somewhere was substituted by Bronislaw (Bronek) Pedrak, Franek Peska, and myself. In Kahl is Main, there was a crowd of people like in a fair. German Peoples were hidden behind closed shutters, after hoisting white flags from the windows, but streets were full of Americans in green uniforms, and jeeps were riding to and from, tooting. We looked after any Polish-speaking soldier. We believed that Americans of Polish origin registered in the Army of their own free will because we were always the valiant nation and always remembered it, so there should be a lot of ours in the green crowd. Our deal was now to find one of them. Americans spoke obstinately in English. But it didn’t last long before we were found. Perhaps our Polish conversations attracted some attention, or perhaps the large white ‘P’ with which we were as Poles labeled by the Germans (in their estimation this was like a bad brand, in our estimation, it was like a distinction). Anyway, the captain who came near us asked in the Polish language.