Original Source Document: Victory Has Many Fathers, But Defeat is an Orphan. William C. Jandrew, American Military University, Feb 19, 2011, MILH 551 – World War II in Europe

(Final Check Doc Snafu September 16, 2022)

Late summer 1944, Rome had fallen, and the massive Allied invasion of Western Europe had bludgeoned Adolf Hitler’s Atlantic Wall, secured the beaches in Normandy, fought through the French hedgerows, and gained momentum in its drive toward Germany. Allied armies, fighting hard, swept northward from southern France, and the Wehrmacht, though offering stubborn resistance, was being driven back toward Germany. Confidence was high as German resistance often resembled headlong flight, and Allied leaders planned the invasion and eventual capitulation of the Third Reich; the question was no longer ‘if’, but ‘how’ and ‘when’ the war was going to end – buoyed by recent success in France and the apparent crumbling of the Wehrmacht, some planners, in their overconfidence, envisioned the occupation of Berlin by the beginning of 1945. Unfortunately, the realities of warfare intruded on the idyllic daydreams of Allied commanders, and in actuality, they were experiencing supply difficulties as their lines grew longer; the advance slowed as lead elements ran short of materiel, mostly fuel and ammunition.

Conversely, German resistance stiffened and supply lines shortened as the Wehrmacht withdrew toward the Rhine River; no longer fighting for foreign territory, they were now fighting for their survival and that of their homes and families. Adding to Allied difficulties, internal squabbles among coalition leaders stymied attempts to form effective invasion plans, and political considerations often overrode military sensibility; who did what was often more important than accomplishing the task at hand?

Ground Forces Commander, Gen Dwight D. Eisenhower, faced with several possibilities, opted for a wide frontal assault on the German Siegfried Line; without a great concentration of force in any one spot, the advance stalled in several areas. The German Army, greatly underestimated, was no longer fleeing, had regrouped, and turned to fight – and what began as reconnaissance in the forests south of Aachen became a lengthy battle of attrition often resembling WW-1 trench warfare; American commanders sacrificed advantages in manpower and armament by staging repeated frontal assaults in unfavorable terrain against determined and prepared defenders, often without a consistent strategic plan.

Ground Forces Commander, Gen Dwight D. Eisenhower, faced with several possibilities, opted for a wide frontal assault on the German Siegfried Line; without a great concentration of force in any one spot, the advance stalled in several areas. The German Army, greatly underestimated, was no longer fleeing, had regrouped, and turned to fight – and what began as reconnaissance in the forests south of Aachen became a lengthy battle of attrition often resembling WW-1 trench warfare; American commanders sacrificed advantages in manpower and armament by staging repeated frontal assaults in unfavorable terrain against determined and prepared defenders, often without a consistent strategic plan.

Only after weeks of heavy losses incurred while trying to dominate the forest did American commanders realize the importance of the Roer River dams beyond the forest and plan accordingly – without control of the dams, ownership of the forest was useless, as the Germans could flood the Roer valley and halt the American drive to the Rhine. By the time they came to realize the importance of the dams, American commanders had committed to a strategy that ignored doctrine and common sense, condemning thousands of men to die in the unnecessary meat grinder that was the Huertgen Forest.

As the Allies drove toward Germany, two major courses were being laid for the events which would occur in the next few months: The Allied High Command was evaluating several different strategies for the invasion of Germany, and the Germans were regrouping, preparing defenses, and doing their utmost to prevent such an invasion. These two issues forced the Allies to choose between keeping them on the run, preventing extensive German preparation while facing dwindling supplies due to ever-lengthening supply lines, or stopping to regroup, shortening supply lines, and facing a rested and fortified German army shortly, extending the war indefinitely. (Robin Neillands, The Battle for the Rhine, The Battle of the Bulge and the Ardennes Campaign, 1944 (New York: Overlook Press, 2005), 30-31)

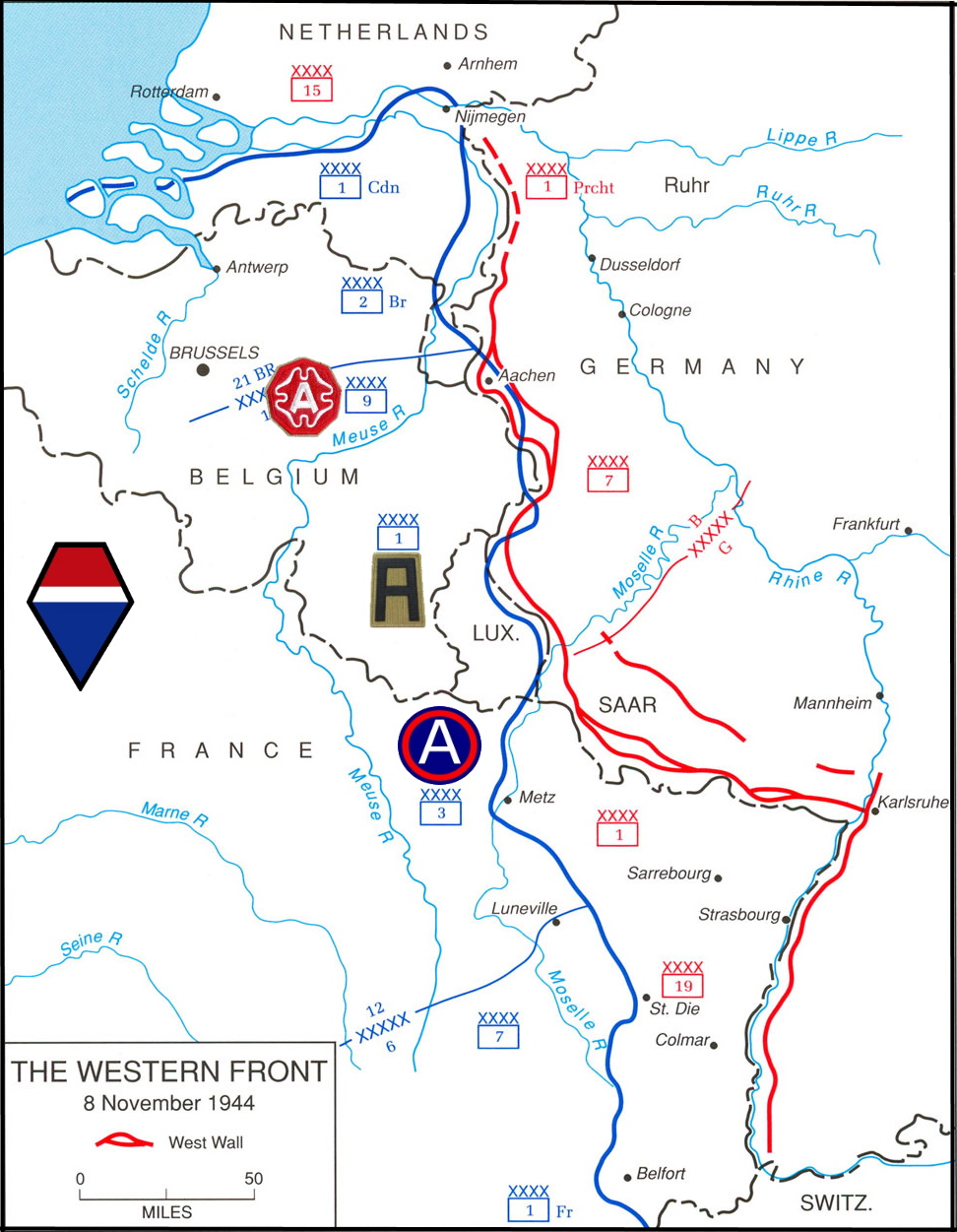

Within that particular issue lay another burning question, one that would have to be addressed no matter what time frame was chosen – how would they enter Germany? A drive to the north of the Siegfried Line through Holland was rejected for reasons of poor terrain (canals, rivers), as was retracing the route through the Ardennes the German blitzkrieg had used a few years earlier (forests, hills); two options remained, pushing through the Siegfried Line at the Aachen Gap or toward the Saar Valley, south of the Ardennes. ((2) Neillands, The Battle for the Rhine, The Battle of the Bulge and the Ardennes Campaign, 1944, 31)

On Sept 1, 1944, Gen Eisenhower also assumed command of all ground forces (SHAEF), replacing FM Bernard Montgomery ((Neillands, The Battle for the Rhine, The Battle of the Bulge and the Ardennes Campaign, 1944, 50),

On Sept 1, 1944, Gen Eisenhower also assumed command of all ground forces (SHAEF), replacing FM Bernard Montgomery ((Neillands, The Battle for the Rhine, The Battle of the Bulge and the Ardennes Campaign, 1944, 50),

and was able to push his so-called ‘broad front’ strategy for the advance on Germany, which would theoretically stretch the German resistance thinly enough to a point where a breakthrough could be exploited while simultaneously providing a safe rear area for supplying the advance (Ted Ballard, Rhineland: The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II (U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1995), 4-5, 13.4) this broad front consisted of Montgomery’s 21st Army Group on the northern flank, First Army and Ninth Army driving west toward Aachen, and Patton’s Third Army moving toward the Saar; one advance that could actually be considered three separate drives (Neillands, The Battle for the Rhine, The Battle of the Bulge and the Ardennes Campaign, 1944, 62

and was able to push his so-called ‘broad front’ strategy for the advance on Germany, which would theoretically stretch the German resistance thinly enough to a point where a breakthrough could be exploited while simultaneously providing a safe rear area for supplying the advance (Ted Ballard, Rhineland: The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II (U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1995), 4-5, 13.4) this broad front consisted of Montgomery’s 21st Army Group on the northern flank, First Army and Ninth Army driving west toward Aachen, and Patton’s Third Army moving toward the Saar; one advance that could actually be considered three separate drives (Neillands, The Battle for the Rhine, The Battle of the Bulge and the Ardennes Campaign, 1944, 62

While the Allies were organizing their advance and trying to solve logistical issues to keep it well-supplied, their supposedly ‘beaten’ German foe was far from defeated and organizing a massive defense at what they called the West wall or, as the Allies knew it, the Siegfried Line. First begun in 1936, it was the German counterpart to France’s Maginot Line, a line of defensive fortifications that initially ran from the area near Holland to just north of Switzerland (Edward G. Miller, A Dark and Bloody Ground: The Huertgen Forest and the Roer River Dams, 1944-1945 (College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 1995), 8 expanded later in the 1930s to stretch along the Belgian border, it had become less a line and more a deep belt of overlapping pillboxes, shelters, command posts, vehicle barriers, and bunkers (Charles B. MacDonald, The Battle of the Huertgen Forest (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1963), 15) that was designed to stop, or at least delay, an invading force. It also used natural terrain features (lakes, rivers, forests) in its defensive construction, and though fallen into disuse and disrepair after the fall of France in 1940, was still a formidable obstacle on its own, even without troops to occupy it (Bruce K. Ferrell, “The Battle of Aachen”, Armor, (November/December 2000): 31). The troops bound to both occupy the West wall and reform elsewhere in the defense of the Fatherland were far from the beaten and ‘bedraggled enemy troops’ (Miller, A Dark and Bloody Ground: The Huertgen Forest and the Roer River Dams, 1944-1945, 99) in headlong flight toward home; even though they were often young teens or old men, (Miller, A Dark and Bloody Ground: The Huertgen Forest and the Roer River Dams, 1944-1945, 24) they were fighting for their homes and families – and waiting for the Americans to come.

While the Allies were organizing their advance and trying to solve logistical issues to keep it well-supplied, their supposedly ‘beaten’ German foe was far from defeated and organizing a massive defense at what they called the West wall or, as the Allies knew it, the Siegfried Line. First begun in 1936, it was the German counterpart to France’s Maginot Line, a line of defensive fortifications that initially ran from the area near Holland to just north of Switzerland (Edward G. Miller, A Dark and Bloody Ground: The Huertgen Forest and the Roer River Dams, 1944-1945 (College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 1995), 8 expanded later in the 1930s to stretch along the Belgian border, it had become less a line and more a deep belt of overlapping pillboxes, shelters, command posts, vehicle barriers, and bunkers (Charles B. MacDonald, The Battle of the Huertgen Forest (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1963), 15) that was designed to stop, or at least delay, an invading force. It also used natural terrain features (lakes, rivers, forests) in its defensive construction, and though fallen into disuse and disrepair after the fall of France in 1940, was still a formidable obstacle on its own, even without troops to occupy it (Bruce K. Ferrell, “The Battle of Aachen”, Armor, (November/December 2000): 31). The troops bound to both occupy the West wall and reform elsewhere in the defense of the Fatherland were far from the beaten and ‘bedraggled enemy troops’ (Miller, A Dark and Bloody Ground: The Huertgen Forest and the Roer River Dams, 1944-1945, 99) in headlong flight toward home; even though they were often young teens or old men, (Miller, A Dark and Bloody Ground: The Huertgen Forest and the Roer River Dams, 1944-1945, 24) they were fighting for their homes and families – and waiting for the Americans to come.

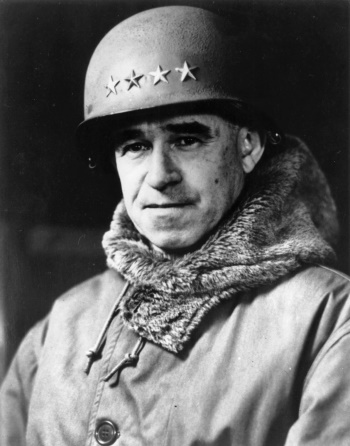

And come they did, with Gen Omar N. Bradley’s Twelfth Army Group (First, Third, and Ninth Armies) in the center; Gen Courtney Hodges’ First Army (V Corps, VII Corps, and XIX Corps) was tasked with punching through the Aachen Gap, south of Aachen and north of the Huertgen Forest; assuming that Aachen would be heavily defended, it would bypass the city and encircle it, taking the heart of the Holy Roman Empire, Charlemagne’s First Reich, and ancestral home to Adolf Hitler’s fading Third Reich (Stephen E. Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers: The US Army from the Normandy Beaches to the Bulge to the Surrender of Germany, June 7, 1944 – May 7, 1945 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1997), 146).

And come they did, with Gen Omar N. Bradley’s Twelfth Army Group (First, Third, and Ninth Armies) in the center; Gen Courtney Hodges’ First Army (V Corps, VII Corps, and XIX Corps) was tasked with punching through the Aachen Gap, south of Aachen and north of the Huertgen Forest; assuming that Aachen would be heavily defended, it would bypass the city and encircle it, taking the heart of the Holy Roman Empire, Charlemagne’s First Reich, and ancestral home to Adolf Hitler’s fading Third Reich (Stephen E. Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers: The US Army from the Normandy Beaches to the Bulge to the Surrender of Germany, June 7, 1944 – May 7, 1945 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1997), 146).

Major road nets radiated from the city’s location in one of the more heavily fortified sectors of the Siegfried Line, and its possession (or destruction) would be a psychological blow to German resistance as well as a boon to transportation and logistics for the future of the advance (Charles B. MacDonald, The Siegfried Line Campaign (Washington DC: US Army Center of Military History, 1963), 28) to the south of Aachen, straddling the German-Belgian border south lay several mountainous and heavily forested areas, (the Meyrode, Wenau, Huertgen, and Rötgen forests) that came to be known collectively as the Huertgen Forest (Robert Sterling Rush, Hell in Hurtgen Forest: The Ordeal and Triumph of an American Infantry Regiment (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1991, 2) a place that American soldiers would come to curse in the coming months.

Despite the capture of Antwerp and the (mostly theoretical, as German resistance continued in the area) use of its ports, logistical issues still haunted the advance and it slowed in early September; a majority of the supplies needed to storm into Germany were still in Normandy, or somewhere in France while en route – either way, they were not where they were needed most (Charles B. MacDonald, The Battle of the Huertgen Forest, 24)

Despite the capture of Antwerp and the (mostly theoretical, as German resistance continued in the area) use of its ports, logistical issues still haunted the advance and it slowed in early September; a majority of the supplies needed to storm into Germany were still in Normandy, or somewhere in France while en route – either way, they were not where they were needed most (Charles B. MacDonald, The Battle of the Huertgen Forest, 24)

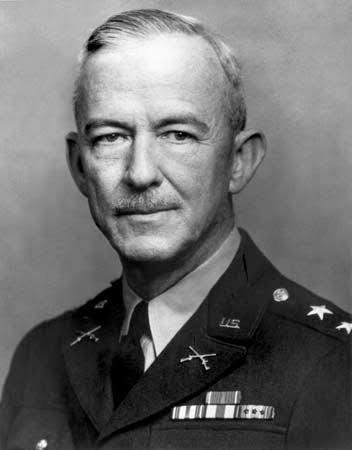

As a result, after successfully crossing the Meuse River and taking back several towns while protecting Montgomery’s flank, Gen Hodges ordered a halt to stockpile fuel and artillery ammunition, allowing only small eastward probes to test enemy strength. Infantry patrols breached the line near Luxemburg on Sept 11 and found empty pillboxes. Lacking much reliable intelligence on enemy activity around the Westwall, (Charles B. MacDonald, The Siegfried Line Campaign, 31 and impatient to breach the Siegfried Line, Gen Joseph ‘Lightning Joe’ Collins (US VII Corps) suggested a so-called ‘reconnaissance in force (per the army’s field manual) between Aachen and the Hürtgen to determine, if possible, enemy resistance; Hodges allowed it so long as resistance was light, and if not, Collins would return and await supplies. Gen Leonard T. Gerow’s V Corps was given a similar order, (Miller, A Dark and Bloody Ground: The Huertgen Forest and the Roer River Dams, 1944-1945, 12) as it was believed that the Germans were responding to the action up north in the Netherlands and down south in Lorraine, as no enemy units of any real significance had been seen in the area for over a week and resistance, if any, was expected to be light (Charles B. MacDonald, The Siegfried Line Campaign, 38). If it were stronger than expected, they could withdraw with some new intelligence, and rest, regroup and resupply as planned.

While the Allies regrouped and prepared to probe the force line, Hitler installed FM Gerd von Rundstedt and FM Walter Model to organize the Westwall defense; (Charles B. MacDonald, The Siegfried Line Campaign, 38) emptying hospitals and rear-echelon and non-combat units, he scraped up roughly 150.000 men to defend against the Allied attacks, from every branch and service – and was graciously and uncharacteristically assisted by Hermann Göring, who combed out Luftwaffe units to provide approximately 30.000 men – about 20.000 paratroopers and roughly 10.000 support crew no longer needed for the faltering Luftwaffe (James M. Gavin, “Bloody Huertgen: The Battle That Never Should Have Been Fought”, American Heritage, (December 1979): 36).

These men were added to severely under-strength units to create the fortress battalions that would defend the Westwall and were supplemented by Himmler’s Volksgrenadier divisions, often raised from teen ‘Hitler Youth’ groups and supposedly infused with Nazi fanaticism; to make up for the smaller division size (10.000 men versus the normal army division size of 12.500), most of these men were armed with submachine guns instead of rifles (Robert Sterling Rush, “A Different Perspective: Cohesion, Morale, and Operational Effectiveness in the German Army, Fall 1944”, Armed Forces and Society, (Spring 1999): 480-482) and possessed more antitank and artillery weapons (Charles B. MacDonald, The Battle of the Huertgen Forest, 14). The men that were regrouping to man the Westwall were not elite soldiers, many could not even be considered ‘whole’ or ‘young’, but they didn’t have to be, as they were moving into and occupying heavily fortified positions designed for just such the defense they were about to mount (Charles B. MacDonald, The Siegfried Line Campaign, 35-36). The tired men of the resurgent German army began to reoccupy the Westwall in force just as the Americans arrived.

September 13 marked General Collins’ and the VII Corps’ penetration of the Scharnhorst Line (the westernmost of the two divergent branches of the Siegfried Line (Westwall), which parted north of Aachen and rejoined it in the Eifel Forest) south of Aachen; he had hoped to break into the Stolberg Corridor, a gap south of Aachen but just north of the town of Hürtgen, and hit the Schill Line (eastern part of the line) in force.

September 13 marked General Collins’ and the VII Corps’ penetration of the Scharnhorst Line (the westernmost of the two divergent branches of the Siegfried Line (Westwall), which parted north of Aachen and rejoined it in the Eifel Forest) south of Aachen; he had hoped to break into the Stolberg Corridor, a gap south of Aachen but just north of the town of Hürtgen, and hit the Schill Line (eastern part of the line) in force.

. The advance consisted of the 1-ID in the north, the 3-AD in the center, and the 9-ID’s 47-IR protecting the southern flank by entering the Hürtgen Forest (Karel Margry, “The Battle of the Huertgen Forest”, After the Battle, (May 1991): 1-5); the German 353. Infantry-Division melted away and allowed elements of the US 3-AG to walk into an ambush by concealed AT guns – it lost six of its eight tanks, (Charles B. MacDonald, The Battle of the Huertgen Forest, 34-35) just a prelude of things to come in the Hürtgen Forest.

. The advance consisted of the 1-ID in the north, the 3-AD in the center, and the 9-ID’s 47-IR protecting the southern flank by entering the Hürtgen Forest (Karel Margry, “The Battle of the Huertgen Forest”, After the Battle, (May 1991): 1-5); the German 353. Infantry-Division melted away and allowed elements of the US 3-AG to walk into an ambush by concealed AT guns – it lost six of its eight tanks, (Charles B. MacDonald, The Battle of the Huertgen Forest, 34-35) just a prelude of things to come in the Hürtgen Forest.

Meanwhile, the 47-IR, finding empty pillboxes and persistent rumors of German render up and down the line (Miller, A Dark and Bloody Ground: The Huertgen Forest and the Roer River Dams, 1944-1945, 21) had easily taken Zweifall on Sept 14 and captured the village of Schevenhutte on Sept 16, encountering up to this point very little resistance. What they didn’t know was that while they were moving west, the German 12.Infantry-Division, fresh and fully staffed and supplied, was brought in by rail to stop the American advance in the Stolberg Corridor and retake Schevenhutte; (Margry, “The Battle of the Huertgen Forest”, 6) for almost a week elements of the

Meanwhile, the 47-IR, finding empty pillboxes and persistent rumors of German render up and down the line (Miller, A Dark and Bloody Ground: The Huertgen Forest and the Roer River Dams, 1944-1945, 21) had easily taken Zweifall on Sept 14 and captured the village of Schevenhutte on Sept 16, encountering up to this point very little resistance. What they didn’t know was that while they were moving west, the German 12.Infantry-Division, fresh and fully staffed and supplied, was brought in by rail to stop the American advance in the Stolberg Corridor and retake Schevenhutte; (Margry, “The Battle of the Huertgen Forest”, 6) for almost a week elements of the  12-ID threw themselves at the Americans in Schevenhutte. Simultaneous action to the south by the American 39-IR (Lt Col Van H. Bond) attempting to push north near Monschau and meet with the 47-IR near Düren met stiff resistance from the German 89.Infantry-Division.

12-ID threw themselves at the Americans in Schevenhutte. Simultaneous action to the south by the American 39-IR (Lt Col Van H. Bond) attempting to push north near Monschau and meet with the 47-IR near Düren met stiff resistance from the German 89.Infantry-Division.

On September 18, General Courtney Hodges, seeing the forest as a place for Germans troops to hide and from which to counter-attack (The few roads that existed were narrow and muddy, barely traversable by tanks) ordered to 60-IR Infantry forward to close the gap between the 39-IR and the 47-IR, and consolidate the line; and so, the 60-IR (Col Van Houten) was the first American unit to fully submerge itself in the dark green gloom of the Hürtgen Forest. High ridges and deep valleys dominated the terrain and tall, ancient trees blocked out the sun, parted only by small trails and narrow firebreaks; there were no clearings worthy of note, except near the villages; but damp wet ground and mud that sucked at shoes and mired vehicles. Only small groups could move about together in the thick wooded darkness, and larger groups lost one another as they constantly crouched under the trees and tried to navigate using inaccurate maps and occasionally, German tourist guides to the forest.

On September 18, General Courtney Hodges, seeing the forest as a place for Germans troops to hide and from which to counter-attack (The few roads that existed were narrow and muddy, barely traversable by tanks) ordered to 60-IR Infantry forward to close the gap between the 39-IR and the 47-IR, and consolidate the line; and so, the 60-IR (Col Van Houten) was the first American unit to fully submerge itself in the dark green gloom of the Hürtgen Forest. High ridges and deep valleys dominated the terrain and tall, ancient trees blocked out the sun, parted only by small trails and narrow firebreaks; there were no clearings worthy of note, except near the villages; but damp wet ground and mud that sucked at shoes and mired vehicles. Only small groups could move about together in the thick wooded darkness, and larger groups lost one another as they constantly crouched under the trees and tried to navigate using inaccurate maps and occasionally, German tourist guides to the forest.

These were just the effects of nature on the men in the forest – the Germans had augmented its natural defenses with deep bunkers, thickly laid minefields, hidden and well camouflaged machine-gun nests with overlapping fields of fire, and pre-sighted artillery to make the most use out of tree-bursts (artillery shells were timed to explode at treetop level, showering the men below not only with shards of metal shrapnel but also with tremendous amounts of splinters of the exploding trees), deep belts of overlapping barbed and concertina wire, and roadblocks loaded with mined booby-traps (Steve Snow, et al. CSI Battle book II-A: Hürtgen Forest (Fort Leavenworth: Combat Studies Institute, 1984), III-3 – III-8).

In entering the forest, Hodges had committed his men to an infantry battle, surrendering their advantages in air power and artillery to the thick forest, and advantages in manpower to the prepared German defenders, whose man-to-man firepower advantage and fortified defenses acted as force multipliers against the besieging Americans. The objectives of the 9-ID on Sept 19, were the towns of Kleinhau and Hürtgen; the 60-IR would take the ominously named Dead Man’s Moor on its way to the town of Germeter, and the 39-IR would take some trails in the nearby Weisser Weh valley and move on to Kleinhau and Hürtgen.