(Document source: this archive was found while searching for papers in the CDs. It was submitted to EUCMH by Elmer T Garvelson (USA) on June 13, 2005. No other information available) (Note I am not late with my publications but burning CDs en mass make things like that happen).

The most important source for the personal aspects of this historical perspective came from hours of oral interviews with my grandmother, Etta Louise Bietz. Her unrelenting attention to detail became this work’s greatest attribute. Michelle L. Ellison.

It was a beautiful afternoon in Lexington, especially in early December. Still, in her Sunday best, Etta Louise Bietz, not quite sixteen, sat in the living room of her family’s small house on Carlisle Avenue. Her uncle and his family were paying a visit, and Etta was enjoying a delightful conversation with her cousins.

It was a beautiful afternoon in Lexington, especially in early December. Still, in her Sunday best, Etta Louise Bietz, not quite sixteen, sat in the living room of her family’s small house on Carlisle Avenue. Her uncle and his family were paying a visit, and Etta was enjoying a delightful conversation with her cousins.

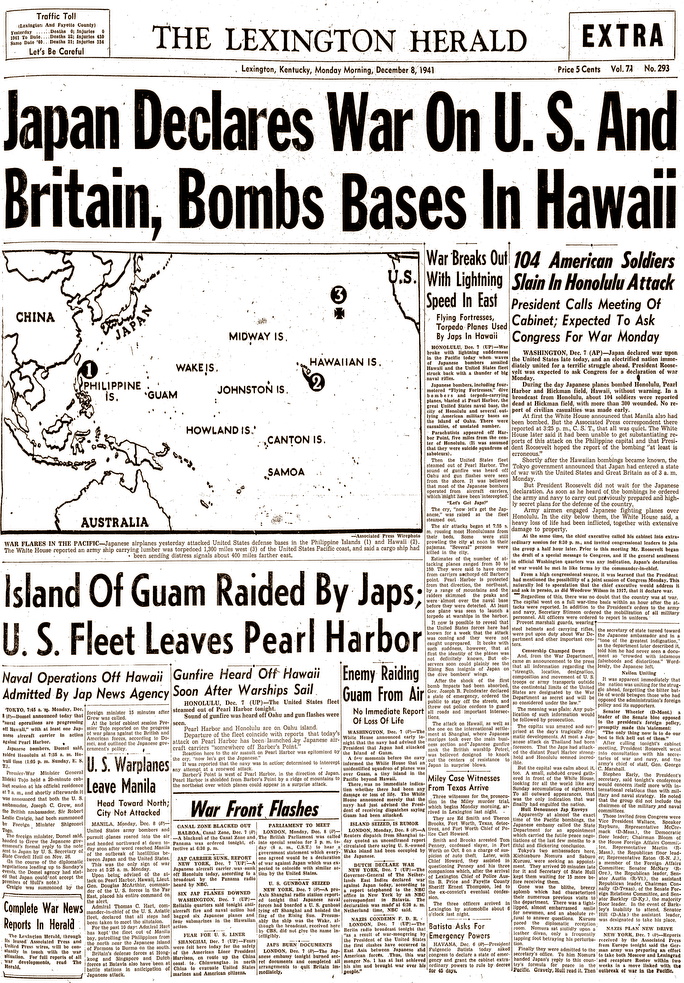

They were interrupted by the sound of a young boy running up the street yelling, Extra, Extra, read all about it! Etta’s mother, Sara Etta Brown Bietz, anxiously handed her a quarter and sent her to fetch the paper, expecting to read about the latest discoveries in the famous Miley murder case that the Herald had been following so closely. When Etta read the headlines, however, she found not the Miley murders, but ‘Japs Bomb Manila, Pearl Harbor; Naval Battle Raging Near Hawaii’.

They were interrupted by the sound of a young boy running up the street yelling, Extra, Extra, read all about it! Etta’s mother, Sara Etta Brown Bietz, anxiously handed her a quarter and sent her to fetch the paper, expecting to read about the latest discoveries in the famous Miley murder case that the Herald had been following so closely. When Etta read the headlines, however, she found not the Miley murders, but ‘Japs Bomb Manila, Pearl Harbor; Naval Battle Raging Near Hawaii’.

At first, Etta did not understand the headline; she had never heard of Manila or Pearl Harbor. As she read further, she began to realize the gravity of this event. Japan had just attacked America. Her mind raced through different ways that war would change all the people she knew. It never occurred to her that she was about to play a huge role in events that would forever change her family, her community, and women everywhere.

On the eve of the Second World War, the country was only beginning to recover from the Depression and still trying to hold on to traditional values. The decade of the thirties tested the fortitude of American families’ fight for survival in the face of unemployment, poverty, and uncertainty about the future. Etta Bietz’s folks were among the many who struggled against the economic hardships that often tore families apart. Mrs. Bietz, along with her husband and five children, had moved to Lexington in 1930, to be closer to her parents. With the birth of their sixth child in 1932, Mr. Bietz’s job in the slaughterhouses barely provided enough income to support the family. Although funds were tight, Mrs. Bietz stretched the resources from a single income to provide the necessities for her four girls and two boys. The Bietz family during the Depression years was not indicative of American families in general; they were able to find the resolve to endure the old-fashioned way. Many families differed from this traditional model of the husband as the breadwinner while the wife takes care of domestic duties.

The emphasis on traditional roles in the home resurfaced when American jobs disappeared during the Depression. Just before the Depression, women had made great strides towards attaining more rights and equality with men. They had begun to strive for careers by entering universities and the workforce, breaking down the traditional roles of women as mainly domestic workers. However, with the onset of the Depression women were encouraged to resume their traditional roles since jobs were scarce, and by working, they might contribute to male unemployment rates.

The position assumed that men alone faced the problem of unemployment. Women allegedly had husbands, brothers, or fathers who were taking care of them. Although this was the case for Etta and her mother and sisters, for many other women nothing could be further from the truth. At the end of the era, more than 11.5 million women were employed. A large number of women were heads of household and had to balance the duties of motherhood and employment without the help of a second income. Jobs were difficult for women to attain and wages, working conditions, and hours were still unregulated. Regardless of how many hours they worked, women were expected to come home and spend another fifty hours or more tending to their families and household duties.

The position assumed that men alone faced the problem of unemployment. Women allegedly had husbands, brothers, or fathers who were taking care of them. Although this was the case for Etta and her mother and sisters, for many other women nothing could be further from the truth. At the end of the era, more than 11.5 million women were employed. A large number of women were heads of household and had to balance the duties of motherhood and employment without the help of a second income. Jobs were difficult for women to attain and wages, working conditions, and hours were still unregulated. Regardless of how many hours they worked, women were expected to come home and spend another fifty hours or more tending to their families and household duties.

Contrary to the perceptions held by many Americans about the Depression Era, some families were solely dependent on a woman’s salary for survival. Often mothers were forced to rely on government handouts because holding a job in a world before childcare was very difficult. Even those women who did have husbands during the thirties often had to work outside the home. By 1939, the median income for families was only $1100 annually. Many wives went to work because their husbands’ incomes barely reached half of the median. By 1940, economic necessity forced 15.5 percent of all married women to work. After laboring long hours, they still contributed less than two hundred dollars a year to their family income. But those two hundred dollars provided the basic necessities—food, clothing, and shelter.

Despite the obvious need for many families to have two sources of income, society responded to the Depression by urging women to resume domestic roles and stay out of the workforce. The growing unemployment rate gave rise to much fear and many people lashed out at working women for taking a job away from a man who needed it. In the public opinion polls of 1939, 78 percent of the population was opposed to married women working.

The government also attempted to pressure women out of the workforce. FDR’s New Deal programs, although intended to help everyone during the Depression, instead strongly discriminated against working women, specifically married women. In 1932, the government announced that only one family member could hold a government job. Naturally, Work Progress Administration (WPA) jobs were given to men first, and many states refused to hire married women altogether. Frances Perkins, Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Secretary of Labor, was a strong supporter of working women and recognized the unfairness of the government’s policies towards women. Mrs. Perkins, a pioneer herself as the first woman on a President’s cabinet, apologetically commented: We had no choice in the Federal Government but to limit one job per family. It was meant to discourage nepotism, but it discriminated against women. She also acknowledged: It is a well-known secret that married women just took off their wedding rings and pretended to be single. How else can you account for the actual increase in the number of married women working during the Depression? Examples to the contrary notwithstanding, American society feared women working, single or married.

The government also attempted to pressure women out of the workforce. FDR’s New Deal programs, although intended to help everyone during the Depression, instead strongly discriminated against working women, specifically married women. In 1932, the government announced that only one family member could hold a government job. Naturally, Work Progress Administration (WPA) jobs were given to men first, and many states refused to hire married women altogether. Frances Perkins, Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Secretary of Labor, was a strong supporter of working women and recognized the unfairness of the government’s policies towards women. Mrs. Perkins, a pioneer herself as the first woman on a President’s cabinet, apologetically commented: We had no choice in the Federal Government but to limit one job per family. It was meant to discourage nepotism, but it discriminated against women. She also acknowledged: It is a well-known secret that married women just took off their wedding rings and pretended to be single. How else can you account for the actual increase in the number of married women working during the Depression? Examples to the contrary notwithstanding, American society feared women working, single or married.

America’s fears were unwarranted. In actuality, working women had no effect on men’s employment opportunities because segregation had already been established in the workforce. Women had traditionally dominated the service industry while men had always been recruited for the manufacturing industry. A look at the classified section of Lexington’s Herald or Leader during the Depression years demonstrates that help-wanted ads had always been a matter of gender.

America’s fears were unwarranted. In actuality, working women had no effect on men’s employment opportunities because segregation had already been established in the workforce. Women had traditionally dominated the service industry while men had always been recruited for the manufacturing industry. A look at the classified section of Lexington’s Herald or Leader during the Depression years demonstrates that help-wanted ads had always been a matter of gender.

The want ads were clearly divided between male help and female help wanted, and even within the ads colored and white were specified. For example, under the heading of Male Help Wanted are ads such as: Wanted—Experienced mechanics; Delivery Boy—Colored, must have own bicycle; Experienced man to work in dairy near Paris, splendid new house for home. Women would have been laughed at had they tried to apply for any of these male-dominated positions. Similarly, men would never have tried to obtain any of the jobs listed under Female Help Wanted: Wanted—Saleslady for ready-to-wear chain store.  Experience necessary; Beauty Operator—Good salary and commission; Wanted—Girls to work in Laundry. Even WPA jobs spread segregation; women were typists, secretaries, clerks, and packers.

Experience necessary; Beauty Operator—Good salary and commission; Wanted—Girls to work in Laundry. Even WPA jobs spread segregation; women were typists, secretaries, clerks, and packers.

For women, the depression had the undesirable effect of crushing whatever strides they had made toward more independence in the twenties with the woman’s movement. Their efforts to establish careers and transgress the gender biases in employment came to an end. Once again, on the eve of war, women were expected to stay at home and care for their families, just as their mothers had done a generation before. Upon hearing the declaration of war on December 8, 1941, few Americans could foresee that in only four short years, America would be altered forever, and all attempts to return to the traditional values that emphasized domestic life would ultimately be in vain.

In the spring of 1941, Lexington remained grounded in its agricultural heritage. After the Depression, life became more centered in the rolling hills and wheat and tobacco fields of Central Kentucky. As summer continued, Lexingtonians knew of the growing hostility in Europe and around the globe only through intermittent headlines in newspapers. However, America was still concerned only about America. Public sentiment supported isolation from world affairs and a return to the prosperous days of the twenties. A peace treaty with Japan seemed possible, and the US involvement in another global theater of war seemed unlikely.

As autumn approached and diplomacy waned, the seeds were being planted that would soon thrust Central Kentucky to the forefront of wartime industry. Lexington architects were working with various War Department Offices in Washington. They were drawing up plans to transform 784 acres of farmland, equidistant from Paris, Lexington, and Winchester in eastern Fayette County, into a military supply depot. The area they had chosen was the small farming community of Avon.

By the spring of 1941, only a select few Kentuckians knew that the War Department, sensing growing tensions in US foreign policy, had already begun building this new Army Post. Lexingtonians were not aware that within a few months more than 1000 families would be connected directly with the small town to be known as the Lexington Signal Depot. The Lexington Signal Depot was created as a part of one of the seven technical branches of the Army, the Signal Corps. The Depot’s original construction included the building of eight 180’x 720’ brick warehouses, a power plant, an internal telephone a communications network, an internal railway system, a motor pool building, a fire department, forty wood-framed temporary buildings, an Administration building. The Signal Corps was the eyes and ears of the Army, and it was to be the mission of the Depot to receive, store, and ship supplies, parts, and equipment throughout the world. It was also responsible for the repair and upgrade of many crucial army radio systems. Jobs at the Depot ranged from Warehousing and Inspection to Plant Maintenance and Security. The Depot was a fully functional autonomous community, complete with police, grocery, recreation, and health care facilities. Construction of this key element of the Signal Corps began July 1, 1941, and was completed within eleven months.

Only four months after the construction of the Depot began, Senator Alben W. Barkley announced that the army would purchase more Kentucky land, this time in Madison County, to build a munitions storage base named the Blue Grass Ordnance (BGO). The Senator’s announcement brought harsh criticism, and apprehension spread through Lexington and the surrounding areas. Hardly anyone desired more Kentucky land to be taken for government use, and seized taxable land would no longer generate county tax revenue. Many folks feared that new families would flood the area, and distress over the possible influx of persons to an already uneasy labor market was apparent in the voices and faces of Central Kentuckians. Few could foresee the opportunities for generating new jobs and creating economic expansion from increased retail patronage. Only some saw the chance for mutual growth between the depots and the community.

Only four months after the construction of the Depot began, Senator Alben W. Barkley announced that the army would purchase more Kentucky land, this time in Madison County, to build a munitions storage base named the Blue Grass Ordnance (BGO). The Senator’s announcement brought harsh criticism, and apprehension spread through Lexington and the surrounding areas. Hardly anyone desired more Kentucky land to be taken for government use, and seized taxable land would no longer generate county tax revenue. Many folks feared that new families would flood the area, and distress over the possible influx of persons to an already uneasy labor market was apparent in the voices and faces of Central Kentuckians. Few could foresee the opportunities for generating new jobs and creating economic expansion from increased retail patronage. Only some saw the chance for mutual growth between the depots and the community.

Despite the negative reactions by Kentuckians, on November 5, 1941, one month before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Army purchased a 14.499-acre tract of land on which to build the second military installation. Construction plans for the BGO included over 900 igloos for ammunition storage, a general supply building, base utilities, and an administrative building. The original purpose of the BGO was to receive, refurbish, store, and ship ammunition and supplies all over the world. The BGO was also instrumental in developing new technologies for both the military and private sectors. The addition of the BGO in the area meant that Kentucky was not only pioneering the advancement of the Signal Corps but would soon be neck and neck with the war industry in the North and West.

When the United States entered the war, the War Department had to act fast. All over America, seemingly overnight, towns began transforming into defense and industrial centers. As a result, consumer production of automobiles came to a halt in early 1942. Auto factories were converted into aircraft plants, new factories were created, and shipbuilding industries expanded. The many new jobs in the defense and war industries ended high unemployment. Numerous jobs opened up for the urban unemployed, and the high pay and high demand also attracted people from rural areas and small towns to the cities. Nationally, migration flowed to the North and West, the traditional centers of industry. Although the nation was heading toward prosperity, the migration caused overcrowding in many cities and often rioting.

However, Kentucky’s groundbreaking strides toward the forefront of wartime industry avoided this problem. Industry drew people out of Lexington and the surrounding areas, into the sparsely populated and traditionally agricultural community of Avon. A great factor in the success of the Depot and productivity in the area as a whole was that people weren’t displaced or drawn into overcrowded cities. As opposed to most other wartime industrial centers, which suffered from overcrowding, Central Kentucky benefited from the Depot’s sustainable growth.

However, Kentucky’s groundbreaking strides toward the forefront of wartime industry avoided this problem. Industry drew people out of Lexington and the surrounding areas, into the sparsely populated and traditionally agricultural community of Avon. A great factor in the success of the Depot and productivity in the area as a whole was that people weren’t displaced or drawn into overcrowded cities. As opposed to most other wartime industrial centers, which suffered from overcrowding, Central Kentucky benefited from the Depot’s sustainable growth.

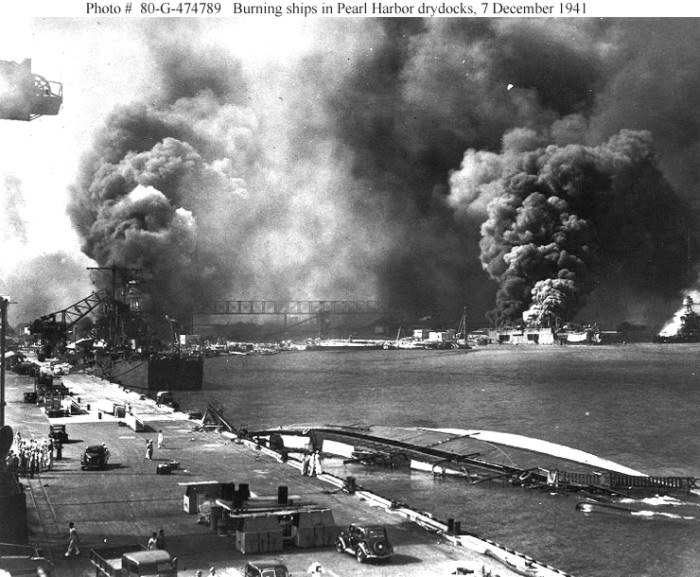

More workers were needed to speed up the construction of the Depot and the BGO following the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor. The War Department brought in workers from different states, and also went on a hiring spree locally. Military personnel and civilians alike were recruited to begin training for jobs at the Depot and the BGO. Training sessions, teaching the use and repair of radio equipment, were held all over Central Kentucky. Training sites in Lexington included Lafayette High School and the Old Johnson School Building, Mayo Vocational School, and the University of Kentucky; additional sites were also established in Paintsville and Paris. More training schools were opened later in Covington, Paducah, Ashland, Owensboro, and Harlan.

By May of 1942, the BGO alone employed over 6500 workers, drawing a combined salary of over $312.000 a week. The Depot employed as many as 3600 personnel at one time. In the nearby towns, retail revenues boomed. Local clubs, hotels, and restaurants saw many new faces coming in. With the increase of retail patronage and the beginning of rationing, shops were often sold out of favorite items. Folks had to stay in close contact with stores to be kept abreast of products arriving daily. Although the Depot was built in anticipation of hostilities abroad and plans for the BGO preceded the attack on Pearl Harbor, no one anticipated that change would come so hastily to Lexington.

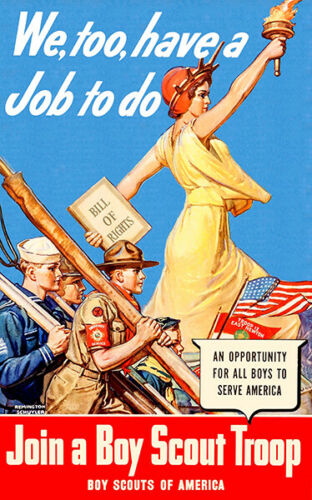

As Kentucky became the vanguard for wartime industry in the South, Lexington families remained unaware of the drastic transformations beginning to manifest throughout America. In the face of employment highs not seen in decades, men were soon called to fight and taken out of the labor pool. As a result, for the first time in years, jobs exceeded workers. The wartime industry had to replenish the workforce by responding quickly and without regard to race or gender. Employers seemed reluctant to hire from the pool of labor that remained—blacks and women. In President Roosevelt’s Columbus Day speech in 1942, he acknowledged this problem: In some communities, employers dislike hiring women. In others, they are reluctant to hire colored people. We can no longer afford to indulge in such prejudice. The War Department quickly realized that new workers must emerge and old prejudices must die, to meet the new demands of society. Potential women workers could no longer be ignored. The War Department recognized this and campaigned to appeal to women for the cause. The War Manpower Commission began sending out a new message to American Women: Get a Job!

A call has gone out for millions of women to exchange kitchen aprons for overalls; for women whose hands are skilled in sewing, cooking, to turn to handle latches, cutting dies, and running drills; for women whose eyes are used to fine sewing to learn to trace blueprints, test precision instruments, and inspect plane parts. All kinds of women are needed, young and old, women who once worked and can work again, and young women new to the factory or job. America experienced a revolution on the home front, as over three million women went to work in defense plants; another 350 thousand women joined the military. The first episode of Wonder Woman by Charles Moulton appeared around this time. At last, in a world torn by the hatred and wars of men, Moulton wrote, appears a woman to whom the problems and feats of men are mere child’s play. Once again, the same societal pressure that only a year ago influenced women to uphold traditional values in the domestic sphere was now urging them to fulfill their patriotic duties; to help their brothers and husbands. How quickly society’s urgings change!