(v. 2023) Document Source: Headquarters Army Ground Force, Army War College, Washington D. C., Report Number 61. Col H. A. Miller; Col Shaffer F. Jarrel, September 22, 1944. Combat Observations. (Transcription & Illustrations Doc Snafu)

In the early years of World War Two, the German Army amply demonstrated its ability to exploit victory to the fullest. After the tide had turned against the Germans, it became apparent that they also possessed the more outstanding ability to quickly recover from a defeat before their opponents could thoroughly exploit their success. Less than a month after suffering an in-apparently decisive defeat in which it was crushed and battered beyond recognition, the German 7.Army (Branderberger) established a coherent front line from the Meuse River to the Schnee Eifel Range in September 1944. Committed in this wide arc and supported by a motley conglomeration of last-ditch reserves, the army’s remaining elements successfully defended the approaches to the Reich. During its withdrawal from the Falaise Gap to the West Wall, the 7.Army passed through three distinct phases.

The 7.Army, following narrowly averted annihilation in the Falaise Pocket, ceased to exist as an independent organization. The 7.Army shattered remnants were attached to Manteufell’s 5.Panzer-Army until September 4, 1944, then was apparently reconstituted under the command of Gen Erich Brandenberger. The 7.Army then passed through the phase of delaying action while it reorganized its forces and re-established the semblance of a front line. Despite persistent orders from above to defend every foot of ground, Brandenberger realized that a fairly rapid withdrawal was called for if his forces were to reach the West Wall ahead of American spearheads. So, delaying action ended officially on September 9, 1944, when the 7.Army was charged with the defense of the West Wall in the Maastricht – Aachen – Bitburg sectors. Along with the fortifications, the army took over all headquarters and troops stationed in this area. Of the 7.Army’s 3 Corps, the LXXXI Corps (Schack) was assigned to the northern sector of the West Wall from Herzogenrath to Düren with a position to Rollesbroich and the Huertgen Forest sector; the LXXIV Corps (Straube) was committed to the center from Roetgen to Ormont and the 1.SS-Panzer-Corps (Keppler) was to defend the West Wall in the Schnee Eifel sector from Ormont to the boundary with the 1.Army (von Knobelsdorff) at Diekirch, Luxembourg.

The 7.Army, following narrowly averted annihilation in the Falaise Pocket, ceased to exist as an independent organization. The 7.Army shattered remnants were attached to Manteufell’s 5.Panzer-Army until September 4, 1944, then was apparently reconstituted under the command of Gen Erich Brandenberger. The 7.Army then passed through the phase of delaying action while it reorganized its forces and re-established the semblance of a front line. Despite persistent orders from above to defend every foot of ground, Brandenberger realized that a fairly rapid withdrawal was called for if his forces were to reach the West Wall ahead of American spearheads. So, delaying action ended officially on September 9, 1944, when the 7.Army was charged with the defense of the West Wall in the Maastricht – Aachen – Bitburg sectors. Along with the fortifications, the army took over all headquarters and troops stationed in this area. Of the 7.Army’s 3 Corps, the LXXXI Corps (Schack) was assigned to the northern sector of the West Wall from Herzogenrath to Düren with a position to Rollesbroich and the Huertgen Forest sector; the LXXIV Corps (Straube) was committed to the center from Roetgen to Ormont and the 1.SS-Panzer-Corps (Keppler) was to defend the West Wall in the Schnee Eifel sector from Ormont to the boundary with the 1.Army (von Knobelsdorff) at Diekirch, Luxembourg.

When the US VII Corps (Collins) launched its reconnaissance in force on September 12, the 7.Army was in the midst of this process of transition. While some of its elements had already occupied their assigned West Wall sectors, others were still fighting a delaying action well forward of the bunker line.

German Defenses – Aachen & Stolberg Corridor

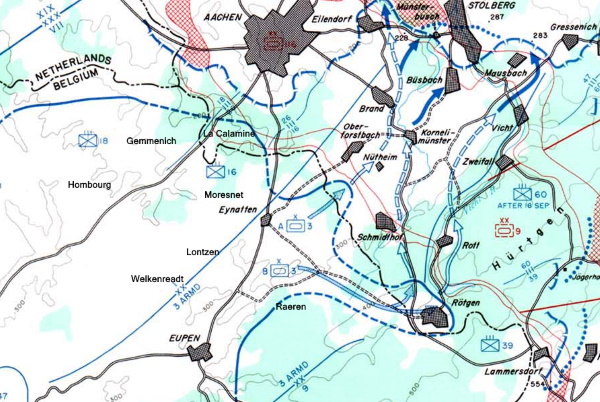

On September 12, the forces of the LXXXI Corps (Schack) were committed from Breust on the Meuse River eastward to Hombourg and Moresnet thence south along the West Wall to the boundary with the LXXIV Corps (Straube) in Eupen – Roetgen – Zülpich – Bonn. Four badly mauled understrength divisions were committed in the LXXXI Corps front line. In the northwestern sector, between the Meuse River and the Aachen area, the 275.Infantry-Division and the 49.Infantry-

On September 12, the forces of the LXXXI Corps (Schack) were committed from Breust on the Meuse River eastward to Hombourg and Moresnet thence south along the West Wall to the boundary with the LXXIV Corps (Straube) in Eupen – Roetgen – Zülpich – Bonn. Four badly mauled understrength divisions were committed in the LXXXI Corps front line. In the northwestern sector, between the Meuse River and the Aachen area, the 275.Infantry-Division and the 49.Infantry-

Division held the line against the US XIX Corps. In the southeastern half of the LXXXI Corps zone opposite the US VII Corps, the 116.Panzer-Division (von Waldenburg) and the 9.Panzer-Division (Mueller) faced the US 1-ID (Huebner) and the 3-AD (Rose). The sector of the 116.Panzer-Division was defined in the northwest by the boundary with the 49.Infantry-Division, Hombourg – Schneeberg Hill – along the West Wall to Bardenberg. In the southeast the boundary with the 9.Panzer-Division, Welkenraedt via Hauset and Brand to Stolberg. The organic strength of the 116.Panzer-Division, was organized in two armored regiments, the 60.Panzer-Grenadier-Regiment and the 156.Panzer-Grenadier-Regiment with the 116.Panzer-Aufklarung-Abteilung and the 116.Panzer-Artillerie-Regiment.

Division held the line against the US XIX Corps. In the southeastern half of the LXXXI Corps zone opposite the US VII Corps, the 116.Panzer-Division (von Waldenburg) and the 9.Panzer-Division (Mueller) faced the US 1-ID (Huebner) and the 3-AD (Rose). The sector of the 116.Panzer-Division was defined in the northwest by the boundary with the 49.Infantry-Division, Hombourg – Schneeberg Hill – along the West Wall to Bardenberg. In the southeast the boundary with the 9.Panzer-Division, Welkenraedt via Hauset and Brand to Stolberg. The organic strength of the 116.Panzer-Division, was organized in two armored regiments, the 60.Panzer-Grenadier-Regiment and the 156.Panzer-Grenadier-Regiment with the 116.Panzer-Aufklarung-Abteilung and the 116.Panzer-Artillerie-Regiment.

The 9.Panzer-Division had only arrived in the LXXXI Corps zone on September 11. Its sector extended from the boundary with the 116.Panzer-Division to the boundary with the LXXIV Corps. According to Brandenberger, its first wave had consisted of but 3 companies of panzer grenadiers (advance detachment of either the 10.Panzer-Grenadier-Regiment or the 11.Panzer-Grenadier-Regiment), 1 engineer company, and 2 batteries of artillery. Gen Schack amalgamated these elements with the remaining forces of the 105.Panzer-Brigade (Volker). Since its attachment to the LXXXI Corps on September 3, this tank brigade had lost most of its armored infantry battalion and all but ten of its tanks. Instead of committing the weak elements of the 9.Panzer-Division in the West Wall, the LXXXI Corps had found it necessary to send these forces into the front line.

Badly mauled on their first day of action, as was to be expected, the remaining elements of the Kampfgruppe 9.Panzer had assembled in Eynatten during the night of September 11/12. They were to fight a delaying action back to their West Wall sector while all other elements of the division still en route from their assembly area at Kaiserslautern were to be committed immediately in the West Wall upon arrival. In addition to the units enumerated above, the LXXXI Corps also commanded the 353.Infantry-Division (Gen Paul Mahlmann). This division was exhausted and possessed very few organic contingents. Far too weak to be committed in a front-line sector, its headquarters and remaining elements were moved to the assigned West Wall sectors of the 116.Panzer-Division and the 9.Panzer-Division to establish liaison with the various headquarters and local defense units in the rear of the LXXXI Corps.

On September 9, the 7.Army had attached to the LXXXI Corps the Wehrmachtbefehlshaber (Military Governor) for Belgium and northern France with his staff and troops, the Kampfkommandant of Aachen (von Osterroth), the 253.Grenadier-Training-Regiment of the 526.Reserve-Division, (the other two regiments of the 526.Reserve-Division, the 416.Grenadier-Training-Regiment and the 536.Grenadier-Training-Regiment, were attached to the LXXIV Corps while the division headquarters, at Euskirchen, remained directly subordinated to the 7.Army) and a strange assortment of independent battalions representing the proverbial bottom of the barrel. Some of these were Luftwaffe Fortress Battalions, Luftwaffe troops organized into infantry battalions usually without sufficient training and poorly armed; others were called Landesschuetzen Battalions a term vaguely equivalent to home guard, and these Landesschuetzen Battalions were usually composed of men from fifty to sixty years old which were quite inadequately armed, without heavy weapons, and composed of men as old as the hills. The situation in the LXXXI Corps area was complicated further by the presence of the Nazi Police and Hitler Youth detachments who attempted to make themselves useful by doing such work on the West Wall as they saw fit but refused to cooperate with the military.

The various independent battalions described above were subordinated to the 353.Infantry-Division (Mahlmann) prior to their commitment to the front-line divisions. By order of the Commander in Chief of the Army Group B (GFM Walter Model) the newly arrived 8., 12. and 19.Luftwaffe-Fortress-Battalions were attached to 353.Infantry-Division on condition that they would be employed only in defense of the West Wall. The division reported that by 1800 on September 12. So, the Schill Line, the eastern and more strongly fortified bunker belt of the West Wall, would be occupied by the 19.Luftwaffe-Fortress-Battalion committed in the area northwest of Würselen northeast of Aachen, the 3.Landesschuetz-Battalion in the area northwest of Stolberg, the 12.Luftwaffe-Fortress-Battalion also in the vicinity of Stolberg, and the 2.Landesschuetz-Battalion south of Stolberg. The 8.Luftwaffe-Fortress-Battalion was designated 353.Infantry-Division-Reserve. Gen Schack learned on September 12 that the first of three full-strength divisions, the 12.Infantry-Division (Engel), the 183.Volksgrenadier-Division (Lange) and the 246.Volksgrenadier-Division (Wilck), destined to reinforce the Aachen area during September 1944 would arrive in the LXXXI Corps sector in a few days.

Hitler had ordered the 12.Infantry-Division, just rehabilitated in East Prussia after service on the Eastern Front, to begin training for the Aachen sector at 0001 on September 14. Southwest of Aachen the forces of the 116.Panzer-Division (von Waldenburg) enjoyed an uneventful night from September 11 to September 12. This enabled them at 0800 on September 12 to occupy positions in Belgium along the railroad from Hombourg to Moresnet and from Moresnet along the Gueule River Creek via Hergenrath to Hauset. The object was to establish a coherent defense line that, based on a railway tunnel and a creek, would facilitate AT defense. The division committed the 156.Panzergrenadier-Regiment on the right, between Hombourg and Moresnet, and the 60.Panzergrenadier-Regiment on the left along the Gueule River. The 116.Panzer-Recon-Battalion was disengaged and recommitted at daybreak north of the Gueule River with the mission to establish contact with the 9.Panzer-Division in Eynatten, Belgium.

The forces of the 116.Panzer-Division found their mobility greatly restricted by the work of overeager German demolition engineers who had destroyed all the Gueule Creek crossings from Moresnet to the north of Eynatten and had blocked all roads leading to the West Wall with the exception of the Moresnet – Gemmenich – Aachen road. These obstacles seriously interfered with Gen von Schwerin’s intention to withdraw to the West Wall on September 12. But during the morning, Gen Schack ordered von Schwerin not to occupy his West Wall sector before receiving special orders from the LXXXI Corps, and to hold out in front of the West Wall generally as long as possible. The lull enjoyed by the 116.Panzer-Division was shattered at noon on September 12 when American tanks probed German defenses north of Montzen and Hombourg.

Shortly thereafter, the storm broke over the heads of the Germans. The American recon was followed up by a tank attack toward Hombourg. At the same time, American armor crossed the railway between Hombourg and Moresnet. American infantry pushed up the road from Hombourg to Voelkerich and Bleyberg. While the 156.Panzergrenadier-Regiment fell back before these attacks, American troops crossed the Gueule River Creek between Moresnet and Hergenrath in the early afternoon and infiltrated the lines of the 60.Panzergrenadier-Regiment. Gen von Schwerin was forced to withdraw at about 1530 in a northwesterly direction from Moresnet along the Gueule River Creek. The peculiar direction of this withdrawal was probably necessitated by the fact that German engineers had blocked the roads leading northeast.

While the 1-ID launched its drive on Aachen and broke through the lines of 116.Panzer-Division, the 3-AD jumped off from Eupen toward Eynatten and crossed the German border at Roetgen in the sector of 9.Panzer-Division. West of the Eupen – Aachen road the Americans took Lontzen and Walhorn; east of the road they pushed into Raeren. From Walhorn they launched a tank attack toward Eynatten, which fell into American hands at 1345. Elements of the 9.Panzer-Division there withdrew northeastward. These elements and the local defense units were under the command of 353.Infantry-Division and were unable to interfere seriously with American operations.

While the 1-ID launched its drive on Aachen and broke through the lines of 116.Panzer-Division, the 3-AD jumped off from Eupen toward Eynatten and crossed the German border at Roetgen in the sector of 9.Panzer-Division. West of the Eupen – Aachen road the Americans took Lontzen and Walhorn; east of the road they pushed into Raeren. From Walhorn they launched a tank attack toward Eynatten, which fell into American hands at 1345. Elements of the 9.Panzer-Division there withdrew northeastward. These elements and the local defense units were under the command of 353.Infantry-Division and were unable to interfere seriously with American operations.

Later in the afternoon, Gen Schack was disturbed by a civilian report that American forces had occupied Rott at 1800, conveying the impression that they had broken through the West Wall south of Rott. The rumor that the Americans were just south of Rott caused panic among the men of a Luftwaffe AAA unit committed at Rott. The 3.Battery, 889.Light-Flak-Battalion of the 7.Flak-Division smashed the optical equipment of their three 20-MM AAA guns, abandoned their positions, guns, equipment, and belongings, and fled. The cause of the false alarm seems to have been an American armored recon patrol on the Aachen – Monschau road. On the evening of September 12, the 353.Infantry-Division reported American armor converging on Roetgen from the west. Elements of the 253.Grenadier-Traning-Regiment observed American tanks and jeeps followed by strong infantry detachments on personnel carriers moving along the Raeren – Roetgen road. Two American tanks and four armored cars accompanied by infantry pushed into Roetgen. One platoon of the security company in Roetgen (the 328.Reserve-Training-Battalion of the 253.Grenadier-Training-Battalion) was pushed into the southern part of the town.

Later in the afternoon, Gen Schack was disturbed by a civilian report that American forces had occupied Rott at 1800, conveying the impression that they had broken through the West Wall south of Rott. The rumor that the Americans were just south of Rott caused panic among the men of a Luftwaffe AAA unit committed at Rott. The 3.Battery, 889.Light-Flak-Battalion of the 7.Flak-Division smashed the optical equipment of their three 20-MM AAA guns, abandoned their positions, guns, equipment, and belongings, and fled. The cause of the false alarm seems to have been an American armored recon patrol on the Aachen – Monschau road. On the evening of September 12, the 353.Infantry-Division reported American armor converging on Roetgen from the west. Elements of the 253.Grenadier-Traning-Regiment observed American tanks and jeeps followed by strong infantry detachments on personnel carriers moving along the Raeren – Roetgen road. Two American tanks and four armored cars accompanied by infantry pushed into Roetgen. One platoon of the security company in Roetgen (the 328.Reserve-Training-Battalion of the 253.Grenadier-Training-Battalion) was pushed into the southern part of the town.

Intensive infantry fighting developed as American armor advanced to the northern periphery of Roetgen. Keeping out of the range of German AT weapons, the tanks fired into the West Wall bunker embrasures, while American infantry guns laid down a heavy barrage in front of the obstacle wall. Low-flying aircraft attacked the obstacles and defense positions. By 1900, the volume of American artillery and tank fire began to dwindle. The Germans remained in possession of all the West Wall fortifications. An hour later German recon found that the Americans had left Roetgen. Around 2000, September 12, American tanks and infantry advanced between the Hergenrath – Aachen road and the Eupen – Aachen road toward the Scharnhorst Line (the first western band of West Wall fortifications) captured Bunker #161 on the Brandenberg Hill, two miles north of Hauset. Forces under the Kampfkommandant of Aachen were immediately committed to a counter-attack to wipe out this American penetration of the West Wall. They failed in this endeavor but were able to stop the American attack temporarily. At the same time, American armored cars and a few tanks also reached the West Wall about half a mile southeast of Schmidthof and apparently decided to lager in this place for the night.