December 16, the Horror Begins

December 16, the Horror Begins

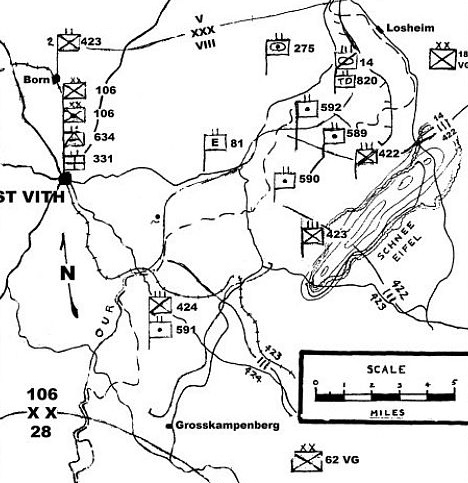

I couldn’t help being reminded of that famous poem by Rudyard Kipling ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’ on that fateful, foggy, grey, cold, drizzling morning Dec 16, 1944. The difference was that instead of ‘cannons’ noted in the poem, we had German tanks to the left of us, tanks to the right of us, tanks in front of us, and tanks behind us. To ‘charge’ ahead would have been to go down the steep slope of an evergreen-covered mountain. The landscape was so much like the mountain areas of Pennsylvania that it was hard to remember that we were in a foreign country fighting a very serious war. Even more seriously, we were surrounded and annihilated by German Panzer Divisions from the left and right of us. German artillery from the front was terrible enough but, to our dismay, the Germans had captured our artillery and were using our guns to fire upon us from the rear. When we called for supporting fire, they were aiming at us instead of their troops. Our Battalion Commander, Col Thomas Kent was killed by a shell coming in from the rear of our ‘Pillbox’ command post. At first, we thought our artillerymen were firing short of their target, but when we heard the German voice on our radio, we realized the awful truth – we were literally at their mercy. The divide-and-conquer strategy used in the German attack had been completely unexpected and effective. The Panzers seemed as numerous as infantrymen would be normally.

I was the Battalion Operations Officer for the 1/422. We were green troops, inexperienced. We had just been brought up to strength by new and very young troops from the United States, Green, and young troops refer to the fact that many of the replacements brought to us to replenish the 106-ID had come from colleges, Army Specialized Training Programs (ASTP), and other academic deferment situations. These men were about 18 years of age on average and very angry at being called to active duty. Worse than that, their indoctrination to duty took place on cold, mud-ridden roads walking across France; along with inadequate equipment, fast movement, and confusion, all of this before the Bulge attack. Despite this, however, they gave a very good account of themselves in a no-win situation – where the 422-IR was demolished.

I was the Battalion Operations Officer for the 1/422. We were green troops, inexperienced. We had just been brought up to strength by new and very young troops from the United States, Green, and young troops refer to the fact that many of the replacements brought to us to replenish the 106-ID had come from colleges, Army Specialized Training Programs (ASTP), and other academic deferment situations. These men were about 18 years of age on average and very angry at being called to active duty. Worse than that, their indoctrination to duty took place on cold, mud-ridden roads walking across France; along with inadequate equipment, fast movement, and confusion, all of this before the Bulge attack. Despite this, however, they gave a very good account of themselves in a no-win situation – where the 422-IR was demolished.

Army Headquarters had put us in this position, just east of St Vith, between Schoenberg in Belgium and Bliealf in Germany, along the Siegfried Line, because they felt that it was the least likely place on the north-south line of our front to be a point of attack – how wrong they were. CCB, 9-AD on our left was either inundated or had pulled out, and the 28-ID on our right flank was being dissected, just as we were. After 72 hours of constant bombarding, we were ordered to ‘attack to the rear’. We had been infiltrated by English-speaking Germans (Panzer-Brigade 150 – Skorzeny) and confusion was rampant. We were being systematically cut to ribbons. Elements of surviving units banded together, forming the most unlikely fighting units.

There were infantry, heavy weapons, artillery, Air Corps, tank, and anti-aircraft men, all pulling together. Then, the inevitable happened – we ran out of ammunition, and we were surrounded, getting point-blank fire from the German Mark V Panther tanks and their deadly heavy power 75-MM guns. We were using wet, freezing ditches for cover, breaking out of traps by running behind the tanks. Many men were cut down in their tracks during these attempts. I was lucky. With 107 bullets and fragment holes in my trench coat, all the buckles shot off my boots and even my belt buckle being

There were infantry, heavy weapons, artillery, Air Corps, tank, and anti-aircraft men, all pulling together. Then, the inevitable happened – we ran out of ammunition, and we were surrounded, getting point-blank fire from the German Mark V Panther tanks and their deadly heavy power 75-MM guns. We were using wet, freezing ditches for cover, breaking out of traps by running behind the tanks. Many men were cut down in their tracks during these attempts. I was lucky. With 107 bullets and fragment holes in my trench coat, all the buckles shot off my boots and even my belt buckle being  shot off; I was not touched by a single piece of metal. Divine Guidance or luck was to follow me through the next 5 months, through seemingly insurmountable odds. My radio operator, by my side, was not so lucky, and like so many others was killed instantly by a direct hit from a 75-MM tank gun.

shot off; I was not touched by a single piece of metal. Divine Guidance or luck was to follow me through the next 5 months, through seemingly insurmountable odds. My radio operator, by my side, was not so lucky, and like so many others was killed instantly by a direct hit from a 75-MM tank gun.

There was something bizarre and unreal about everything happening. As I glanced over my right shoulder, I saw a Major standing dumbfounded with a spent bullet sticking rakishly out of his neck and another officer reaching over and pulling it out in a nonchalant manner, then wrapping a handkerchief around the Major’s throat. My immediate and irrelevant thought was that you can’t put a tourniquet around somebody’s throat but I guess you can because the Major lived. We continued to try to break out and establish a position that we could defend. As we retreated in the most orderly fashion we could, we began to accumulate men from all different units. The retreat was confused but we kept fighting with what ammunition we could find. On the first night out in our retreat, we pulled into the woods for cover and to rest. Much to our amazement, a large unit of German Soldiers was on the other side of this same woods.

They were being as quiet as we were, not being sure, I feel, what they were facing. We could not estimate the size of this unit, and evidently, they were not sure either since they made no move to come to us. Since we were out of ammunition and could not risk a confrontation, we did not move toward them, nor in any way disclose our position. At dawn, we were moving out of the woods and noted that the Germans had already abandoned the woods during the night. We rapidly moved to the west, but we were finally surrounded by a solid wall of German tanks. For 2 days they circled our position, playing Benny Goodman records, shouting out over loudspeakers how stupid we were to die for a lost cause and propagandizing us with the disloyalty of our wives and sweethearts at home; none of which we believed for a minute. They would then announce a five-minute break ‘for an artillery barrage’. They continued this process until few trees were standing in what had been a heavily wooded, evergreen forest. There were few men alive and not wounded. It was under these conditions that the decision to surrender was made and I will never be able to forget the anguished cries of two young Polish soldiers who had escaped from their German captors in Poland the previous year and made their way to the United States just to join the United States Army, to return to the war to help liberate their own country. Now they faced the same fate of capture once again.

They were being as quiet as we were, not being sure, I feel, what they were facing. We could not estimate the size of this unit, and evidently, they were not sure either since they made no move to come to us. Since we were out of ammunition and could not risk a confrontation, we did not move toward them, nor in any way disclose our position. At dawn, we were moving out of the woods and noted that the Germans had already abandoned the woods during the night. We rapidly moved to the west, but we were finally surrounded by a solid wall of German tanks. For 2 days they circled our position, playing Benny Goodman records, shouting out over loudspeakers how stupid we were to die for a lost cause and propagandizing us with the disloyalty of our wives and sweethearts at home; none of which we believed for a minute. They would then announce a five-minute break ‘for an artillery barrage’. They continued this process until few trees were standing in what had been a heavily wooded, evergreen forest. There were few men alive and not wounded. It was under these conditions that the decision to surrender was made and I will never be able to forget the anguished cries of two young Polish soldiers who had escaped from their German captors in Poland the previous year and made their way to the United States just to join the United States Army, to return to the war to help liberate their own country. Now they faced the same fate of capture once again.

They pleaded with us saying, ‘You don’t know what it is like. We have come so far and all for nothing. We will not go’. Saying this, they hid in foxholes without taking into account the SS method of finally clearing an area by dropping hand grenades into all possible hiding places. We were able to pull the screaming soldiers out before they were blown to bits by grenades. After rounding us up, the SS unit took us to a collecting point in a nearby woods and ordered immediate departure to the east. We erroneously assumed that we were to be evacuated but to our horror saw that the line was being marched past a machine gun emplacement, and men were systematically being shot down where they stood or when they passed. It was inhuman; we were outraged and scared beyond belief. No American could conceive of this kind of savagery. Some men tried to run but were shot as they left the column.

Death seemed inevitable, and then again Divine Intervention in the form of a young Wehrmacht Captain, showing as much anger and disbelief as we were showing, broke the line and shouted to us, ‘Don’t go there, follow me, run for your lives’. We needed no urging and immediately cut to our right, down a very steep mountain grade, stumbling, falling, and dodging the volley of bullets from the frustrated SS troops. It was a nightmare. We lost many men but most of us fell down the mountain and out of that danger. Little did we suspect that we had just begun 140 days of constant walking, freezing, starving, and living an existence that was always near death. We were headed for Koblenz and the crossing of the Rhine River into enemy territory and incarceration. In all of our training for battle, we were never mentally prepared for the contingency of capture. The anxiety, fear, doubt, and disbelief were overwhelming. The Germans had us. We were no longer free to do our own bidding.

Death seemed inevitable, and then again Divine Intervention in the form of a young Wehrmacht Captain, showing as much anger and disbelief as we were showing, broke the line and shouted to us, ‘Don’t go there, follow me, run for your lives’. We needed no urging and immediately cut to our right, down a very steep mountain grade, stumbling, falling, and dodging the volley of bullets from the frustrated SS troops. It was a nightmare. We lost many men but most of us fell down the mountain and out of that danger. Little did we suspect that we had just begun 140 days of constant walking, freezing, starving, and living an existence that was always near death. We were headed for Koblenz and the crossing of the Rhine River into enemy territory and incarceration. In all of our training for battle, we were never mentally prepared for the contingency of capture. The anxiety, fear, doubt, and disbelief were overwhelming. The Germans had us. We were no longer free to do our own bidding.

The German Captain could do with us what he chose. Stories of brutality, death, experimentation, the horrible treatment of the Jews, and hundreds of other thoughts raced through our minds and chilled our blood. ‘Go this way, Go that way’. ‘Take off your clothes’. ‘Put your equipment here’ and ‘Verboten, Rausch, Haltzen, Kommen sie herein’ all became familiar commands, always backed up with a sadistic gesture, a rifle, and a push. Even though the Wehrmacht Captain had saved our lives, there was no love lost between us and we were quickly indoctrinated with the futility of thoughts of escape or expecting any special treatment.

The German Captain could do with us what he chose. Stories of brutality, death, experimentation, the horrible treatment of the Jews, and hundreds of other thoughts raced through our minds and chilled our blood. ‘Go this way, Go that way’. ‘Take off your clothes’. ‘Put your equipment here’ and ‘Verboten, Rausch, Haltzen, Kommen sie herein’ all became familiar commands, always backed up with a sadistic gesture, a rifle, and a push. Even though the Wehrmacht Captain had saved our lives, there was no love lost between us and we were quickly indoctrinated with the futility of thoughts of escape or expecting any special treatment.

The First 100 Miles we Learn Self-Defense

We felt lucky to be alive but we were still full of terror, dismay, and confusion resulting from our recent experience. At the time we had no real idea of a destination, just relief that it wasn’t a machine gun slaughter. The Captain and the Guard were moving us along quickly and soon the sound of the intense battle began to recede.

Koblenz, with its many bridges crossing the Rhine, soon appeared downstream. We were privileged to walk along the beautiful shores of the River and see in the distance the famous ‘Rhine Castles’. They soon faded from sight and memory as we encountered the confusion at the  bridges which were available to cross over to Koblenz. We were all fearful and at the same time ever hopeful that our planes would bomb the bridges before we could be taken across. This seemed a very logical plan because it would stem the German reinforcements and shorten their advance to the west. To our dismay, there were no planes. The heavy fog and clouds had grounded all of our planes. This was one of the factors which had permitted the German Army to make the successful attack which had resulted in our being captured at this point and at this time. The darkness and overcast sky matched our spirits, and we wondered how long it would be before our planes could get into the air again and possibly save us from any further incarceration. We started our crossing of the river; crowding, pushing, and struggling against the tide of the German soldiers being rushed to the west to reinforce their troops and their supply lines. Every type of vehicle was being employed: tanks, motorized half-tracks, horse-drawn carts, and even bicycles. Soldiers were walking ahead of, behind, and alongside the vehicles, catching a ride when they could but always surging forward in a huge mass. It was a nightmare for everybody, soldiers, civilians, and prisoners of war all seemed to be confused.

bridges which were available to cross over to Koblenz. We were all fearful and at the same time ever hopeful that our planes would bomb the bridges before we could be taken across. This seemed a very logical plan because it would stem the German reinforcements and shorten their advance to the west. To our dismay, there were no planes. The heavy fog and clouds had grounded all of our planes. This was one of the factors which had permitted the German Army to make the successful attack which had resulted in our being captured at this point and at this time. The darkness and overcast sky matched our spirits, and we wondered how long it would be before our planes could get into the air again and possibly save us from any further incarceration. We started our crossing of the river; crowding, pushing, and struggling against the tide of the German soldiers being rushed to the west to reinforce their troops and their supply lines. Every type of vehicle was being employed: tanks, motorized half-tracks, horse-drawn carts, and even bicycles. Soldiers were walking ahead of, behind, and alongside the vehicles, catching a ride when they could but always surging forward in a huge mass. It was a nightmare for everybody, soldiers, civilians, and prisoners of war all seemed to be confused.

After getting across the river, it seemed that a direction had finally been determined and I first heard of a town called Falkenberg, the only significance of this being that at that point we were supposed to be transported by train to another destination but tragically this plan was doomed to failure. Getting out of Koblenz was no easy task. The streets we were traveling were extremely narrow, the houses being built close together and to the curbs. Koblenz was not a modern city by our standards. Masses of humanity were on the move and the German trucks and tanks were moving in the opposite direction from our column.

Often it was nearly impossible to get around a tank making a turn around the corner without being crushed by it. There were angry shouts of orders from the German Guards and we did not always know what was being said but the sign language is very effective in getting a point across, especially when accompanied by a push, a shove, or a rifle butt across your head. We had never really comprehended what the language barrier meant until this time. German guttural sounds were no longer humorous but deadly serious and certainly malicious. There was a tendency on our part to silently make fun of the guttural sounds we heard. There were a few men who knew a limited number of German words that they had learned in high school or college but under these circumstances, a few words didn’t help much.

(Hasenven, between Lanzereath and Manderfeld, Belgium) Google Map Exact Location – 50°20’45.6″N 6°20’36.5″E