Between 1933 and 1935, the Navy conducted aerial reconnaissance of the Aleutians to survey potential base sites, Unalaska and Adak being considered the best locations. A weather station was also established at Kiska in 1934-1935. The 1935 Fleet Problem XVI was held in Aleutian waters. It was shadowed by a Japanese trawler escort, and residents of various islands reported the presence of an unusual number of Japanese fishing boats and scientific and cartographic expeditions. The State Department was informed, but it was decided that no protest should be filed to avoid creating an incident with Japan.

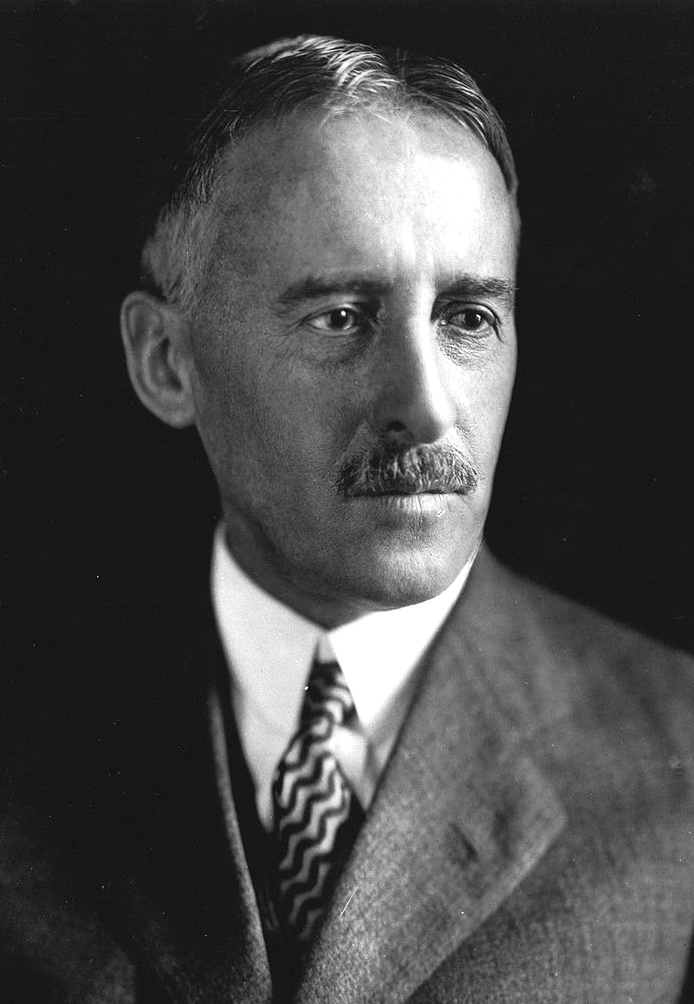

Increasing tensions with Japan during the 1930s and the development of new military technology, especially aircraft, brought Alaska to the attention of planners. There was concern that long-range bombers could reach Alaska and, from bases in Alaska, the West Coast. The consensus was that the key to Alaska’s defense lay in denying to the enemy actual or potential bases from which air or naval operations could be conducted. Still using War Plan Orange as the basis for decisions, the Navy convened the Hepburn Board (headed by Adm Arthur J. Hepburn) to study Naval aviation and readiness. In 1938, the Hepburn Report recommended that the Navy expand the seaplane base designated at Sitka in 1937, and build air facilities at Kodiak and Dutch Harbor as well. These recommendations made it through Congress, and appropriations were voted for FY 1940.

The Navy received priority since its mobility and ability to operate in Alaska was considered superior to that of the Army, though the fact that Franklin Roosevelt as a former Assistant Secretary of the Navy had a certain bias towards the Navy may have influenced the acceptance of the Navy’s viewpoint. The Hepburn Report’s conclusions were also supported by Gen Henry Arnold, Chief of the Army Air Corps and leader of the Alaska Flight of 1934, who insisted that Army bases were necessary to protect the naval facilities, though Arnold’s espousal may have represented a ploy to both assure a role for the Army and to gain recognition for his Air Corps.

Traditional military planning had been confined to calculations of how to meet an attack on American territory by individual nations, but by 1938 the need for a new hemisphere-wide defense was clear. The Joint Army/Navy Board undertook to reassess defense plans under the most unfavorable foreseeable developments in World Affairs. The result was a series of Rainbow Plans, of which the final iteration was R5. The 1939 plan mandated the development of Alaskan defenses. In any Pacific engagement, the Navy would be expected to play the primary role both offensively and defensively at least in the early stages, as the Army lacked troops on the ground and the means to project power in that theater.

Tactically, the plan declared that the Army would be given responsibility, along with the Marines (who were to play a minor role in Alaska), for the defense of Navy shore installations. The two services agreed that duplication of facilities should be avoided and that most could be shared. It was further agreed that Army facilities at such bases would be constructed through existing Navy contracts with civilian firms.

When war broke out in Europe in September 1939, there were about 200 Signal Corps personnel and an additional 300 Army troops at Chilkoot Barracks plus a handful of Navy personnel overseeing various construction projects at Dutch Harbor and other locations. The 286 enlisted men and 11 officers at Chilkoot were armed with 1903 Springfield rifles and used their Russian cannon, the only artillery piece in Alaska, as a flowerpot. There were no roads into the base and the only transportation link with the outside was a tugboat unable to make headway against a 15-knot wind. As Territorial Governor Ernest Gruening observed with considerable overstatement, a handful of enemy parachutists could capture Alaska overnight.

World War II in Alaska

World War II in Alaska

(1939-1946)

Buildup (1939-1942)

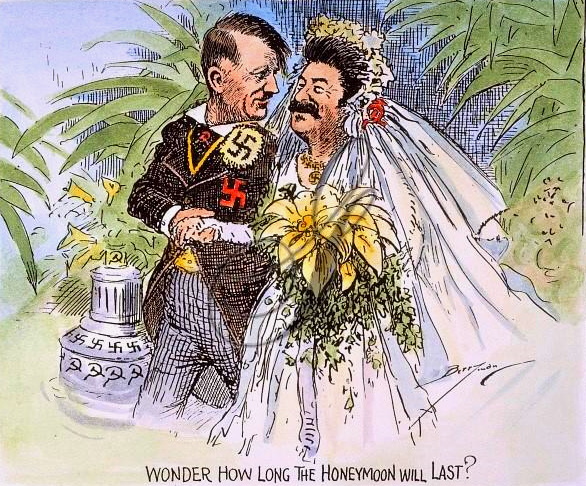

In Aug 1939, Germany and the USSR signed a nonaggression pact which led to the partition of Poland after the German attack in September. In Dec, there were reports of a Soviet military buildup in Siberia, leading to strident calls for the defense of Alaska. However, it was the end of the phony war in Europe and the fall of the Low Countries and France in the spring of 1940, which finally galvanized the country. In Jun 1940, Gen George V. Strong of the Army’s War Plans Division argued that the US should look to hemispheric defense and take an essentially defensive posture in the Pacific. This argument was reiterated in November by Adm Harold Stark, Chief of Naval Operations, in a document is known as Plan Dog, which was to set a broad Allied strategy for the war, an active offensive stance in the primary European sector and a reactive defensive stance in the Pacific. As regards Alaska by early 1940, the War Department had agreed on a long-range program having five major objectives, to augment the Alaska garrison; to establish a major base for Army operations near Anchorage; to develop a network of air bases and operating fields within Alaska; to garrison the airfields with combat forces; and to provide troops to protect the naval installations at Sitka, Kodiak, and Dutch Harbor.

The defense of the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the US and of the Western Hemisphere in general became a more pressing concern, as did the issue of Canada’s participation. Canada had declared war in support of Great Britain and had only limited military supplies available due to massive shipments of its reserves to Europe. Rainbow Plan 4 (R4) recognized Canada as an ally and recommended cooperation.

The defense of the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the US and of the Western Hemisphere in general became a more pressing concern, as did the issue of Canada’s participation. Canada had declared war in support of Great Britain and had only limited military supplies available due to massive shipments of its reserves to Europe. Rainbow Plan 4 (R4) recognized Canada as an ally and recommended cooperation.

The framework for this cooperation was found in the Joint Basic Defense Plan of 1940, and the more definitive Joint Canadian-United States Pacific Coastal Frontier Defense Plan N°2 (ABC-Pacific-22) of 1941. Joint Task Four, the defense of Alaska, gave the Canadian Army no specific responsibilities and assigned the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) a secondary, supporting role. The mainstay of cooperation was the exchange of information and intelligence, the integration of communications and air warning systems, and the coordination of harbor and coast defenses.

The most important collaboration lay in the development of the Northwest Staging Route, a string of airfields between Great Falls MT and Fairbanks AK, for the support of air traffic to and from Alaska. This interior route, which would later be augmented by the Alaska Highway (generally known as the ALCAN Highway) land route, was considered important as an alternative supply link should enemy surface and/or submarine activity interdict ship traffic along the coast, the Inside Passage, or in the Gulf of Alaska.

The slowness of the buildup reflected the hesitancy with which the nation and its leadership moved from a position of neutral isolationism to one of belligerency from the mid-1930s to 1941. The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and the Sino-Japanese War from 1937 on, plus such events as the sinking of the US Gunboat Panay in 1937, the annexation of Austria, the Munich Conference, and the cession of the Sudetenland in 1938, not to mention the outbreak of hostilities in Europe in 1939, pointed to an impending conflict of supra-local scope and intensity, but the US remained immersed in domestic concerns.

Only gradually did public sentiment and Executive and Congressional interest shift towards the exercise of an international leadership role. Roosevelt’s reelection to an unprecedented third term by a wide margin gave him the leeway necessary to change course from recovery and restructuring at home to a foreign policy focus. The Strong Memo prior to the election had little effect, but the Stark Memo (Plan Dog) was readily embraced after it.

Roosevelt had already appointed two prominent Republicans and internationalists, Henry L. Stimson and Frank Knox, as Secretaries of War and the Navy to underscore national unity and a new outward-looking emphasis. Policy goals were to oppose aggression, defend the US and develop the capability to actively enter the fighting if necessary. The necessity appeared more likely as, following successes in Europe, Germany, Italy, and Japan signed a mutual-assistance pact in September 1940, forming the Axis Alliance. The US enacted the first draft law since World War I. Before the Alaska garrison could be augmented according to plan, facilities would have to be constructed, largely from scratch. Following the uphill battle waged by Alaskans and defense advocates, the first modern military construction in the Territory began in 1939. The FY 1940 budget contained $4 million for a military cold weather testing facility to be built at Fairbanks plus about $15 million for the recommended naval construction at Sitka, Kodiak, and Dutch Harbor. With the beginning of these projects, defense spending became the mainstay of Alaska’s economy, a situation that would continue for the next 20 years.

Roosevelt had already appointed two prominent Republicans and internationalists, Henry L. Stimson and Frank Knox, as Secretaries of War and the Navy to underscore national unity and a new outward-looking emphasis. Policy goals were to oppose aggression, defend the US and develop the capability to actively enter the fighting if necessary. The necessity appeared more likely as, following successes in Europe, Germany, Italy, and Japan signed a mutual-assistance pact in September 1940, forming the Axis Alliance. The US enacted the first draft law since World War I. Before the Alaska garrison could be augmented according to plan, facilities would have to be constructed, largely from scratch. Following the uphill battle waged by Alaskans and defense advocates, the first modern military construction in the Territory began in 1939. The FY 1940 budget contained $4 million for a military cold weather testing facility to be built at Fairbanks plus about $15 million for the recommended naval construction at Sitka, Kodiak, and Dutch Harbor. With the beginning of these projects, defense spending became the mainstay of Alaska’s economy, a situation that would continue for the next 20 years.

The facility at Fairbanks, to be known as Ladd Field after Army aviator Maj Arthur K. Ladd, had been in the works since 1936, when the site was selected; it was set aside by executive order in 1937. The official Draft History state that surveying and clearing began in 1938, which would make it the first actual buildup-related construction in Alaska, though serious construction is generally considered to have begun in 1939, after the appropriation of funds.

The facility at Fairbanks, to be known as Ladd Field after Army aviator Maj Arthur K. Ladd, had been in the works since 1936, when the site was selected; it was set aside by executive order in 1937. The official Draft History state that surveying and clearing began in 1938, which would make it the first actual buildup-related construction in Alaska, though serious construction is generally considered to have begun in 1939, after the appropriation of funds.

The facility was not finally authorized until February 1940. Ladd Field was dedicated in September 1940, after around-the-clock shift work over the winter using QM Corps personnel and some civilian contract labor (Cory & Joslyn Co of San Fransisco built the heating plant). The runway reportedly used more concrete than was present at the time on all of Alaska’s roads and sidewalks, and the facility possessed some of the few permanent structures (including some of the reinforced concrete) to be built in Alaska during the war. In addition to the construction involved with the actual field and support facilities, it was found that flood control was necessary to protect the site, and a 3-mile dike was constructed along Chena Slough in 1941.

The mission of Ladd Field was not combat-related. Its initial aircraft complement consisted of one 0-38F observation biplane, though this was increased by two B-17Bs and two YP-37s (one of each was to crash in tests). By the end of World War II, virtually every type of aircraft, including some of the foreign designs, had been tested. Additionally, many items of equipment, clothing, and other material used by the Army Air Forces had been scrutinized under the cold weather conditions of central Alaska. It was not until June 1940, that an Army Air Corps base with a combat role, Elmendorf Field at Fort Richardson, was begun, fulfilling the second point of the plan by establishing an operating base in the Anchorage area.

The Navy also began development of air facilities at Sitka, Kodiak and Dutch Harbor in 1939. In August 1939, the Bureau of Yards and Docks signed contract NOy-3570 (cost-plus-fixed-fee) with Siems-Drake-Puget Sound, a coventure among Johnson Drake and Piper Company (Minneapolis, MN), Siems Spokane Company (Spokane, WA) and Puget Sound Bridge and Dredging Company (Seattle, WA). The contract was originally valued at $15 million and involved 40 projects at Kodiak, 30 at Sitka, and 20 at Dutch Harbor, which was designated somewhat later. The first naval facility to be built was the Sitka Naval Air Station, initially completed in October 1939. During planning and construction, the Sitka installation went from an Advanced Seaplane Base in 1937 to a Fleet Air Base in 1938, a Naval Air Station when commissioned in 1939; and finally, a Naval Operating Base status followed in 1942. The various designations represent the mission and range of facility designations. Some structures from the Navy coaling station, which closed in 1912, were reused, including a coal shed that was converted into quarters for construction crews.

The contractor reported that construction disturbed numerous archeological remains dating to the Russian occupation of Japonski Island, which served to complicate construction (Siems-Drake-Puget Sound). Construction began at Kodiak in September 1939, with the facility being commissioned as a Naval Air Station in February 1941; it subsequently became a Naval Operations Base and served as Navy Command Headquarters. Construction began at Dutch Harbor in September 1940, considerably later than at closer-in locations. The facility was commissioned as a Naval Section Base in 1941 and upgraded to a Naval Air Station a few months later.

The lands for Fort Richardson were set aside in April 1939, and construction began in June 1940. The funds’ authorization was initially cut from the budget, despite lobbying by Gen Marshall and Gen Arnold in spring 1940, leading Delegate Dimond to complain of economy by annihilation. The invasion of the Low Countries led to the rapid approval of a $1.2 billion military appropriation, including $12.8 million for the Fort Richardson project, in May. For the first time, the military budget exceeded $1 billion. The facility was built with contract labor furnished by Bechtel-McCone-Parsons and is illustrative of some of the difficulties encountered in Alaskan construction during the buildup. The weather, of course, made construction uniquely difficult, but other aspects of administration were exacerbated by the particular situation in Alaska.

By August 1941, there were a total of 3415 civilian workers on the job. The Army Corps of Engineers (ACOE) was not given direct responsibility for the work at Ladd and Elmendorf Fields until January 1941, when Capt Benjamin B. Talley was appointed Chief Engineer. He inherited a complex series of headaches. First, there was inadequate housing for personnel, and the contractor set up a facility, Anderson’s Camp, for contract workers primarily brought in from outside the state. There were problems of jurisdiction over the camp and complaints about law and order, theft of materials and gambling (perhaps sponsored by the camp management). Labor unrest and contractual agreements also posed problems, with the Army threatening to use (and ultimately using) troops for various tasks to deal with potential labor stoppages. The position of the unions was that premium hardship rates should be paid and that only union labor and work rules should be allowed, while the military took the position that a national emergency and patriotism should override rigid work rules and premium pay schedules. Inflation also played a significant role in all of this: in Anchorage, consumer prices rose between 25-30 percent in the first six months of 1941.

By August 1941, there were a total of 3415 civilian workers on the job. The Army Corps of Engineers (ACOE) was not given direct responsibility for the work at Ladd and Elmendorf Fields until January 1941, when Capt Benjamin B. Talley was appointed Chief Engineer. He inherited a complex series of headaches. First, there was inadequate housing for personnel, and the contractor set up a facility, Anderson’s Camp, for contract workers primarily brought in from outside the state. There were problems of jurisdiction over the camp and complaints about law and order, theft of materials and gambling (perhaps sponsored by the camp management). Labor unrest and contractual agreements also posed problems, with the Army threatening to use (and ultimately using) troops for various tasks to deal with potential labor stoppages. The position of the unions was that premium hardship rates should be paid and that only union labor and work rules should be allowed, while the military took the position that a national emergency and patriotism should override rigid work rules and premium pay schedules. Inflation also played a significant role in all of this: in Anchorage, consumer prices rose between 25-30 percent in the first six months of 1941.

(Above) Officers quarters receive some exterior work at Elmendorf Field Sept 8, 1941. Before the Alaska District formed in 1946, the Seattle District managed Army Corps of Engineers activities in Alaska. The War Department placed all Alaska military construction under the Corps starting in 1941. Construction on Elmendorf Field began June 8, 1940, as a major and permanent military air field near Anchorage. The first Air Corps personnel arrived Aug 12, 1940. The War Department formally designated Elmendorf Field as Fort Richardson Nov 12, 1940, but the air facilities on the post were named Elmendorf Field in honor of Capt Hugh M. Elmendorf, killed in 1933 while flight testing an experimental fighter near Wright Field, Ohio (Source US Army Corps of Engineers Alaska District)