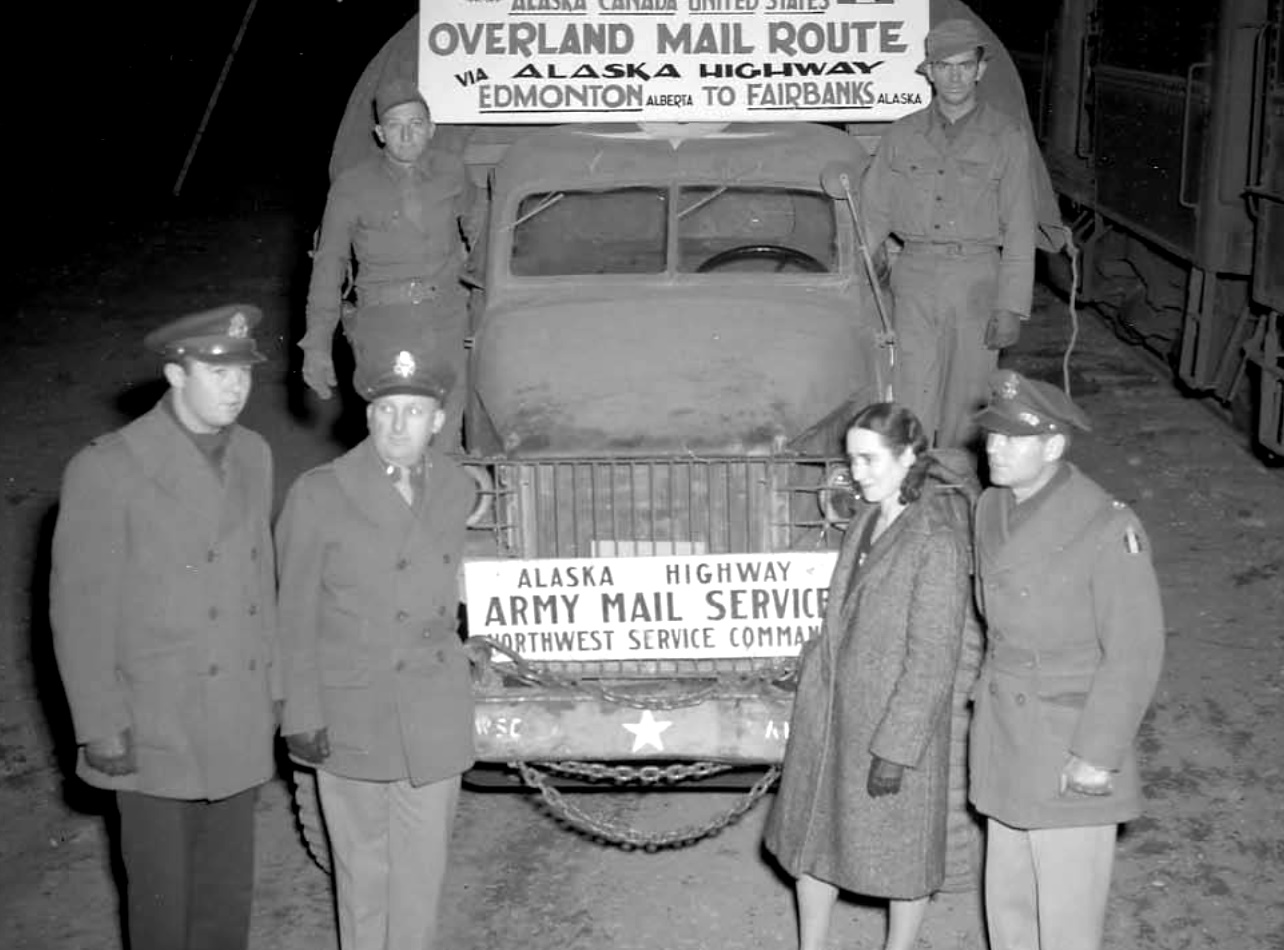

Supplies often could not be purchased locally at any price, and delays in shipments (and mismatches in items requisitioned, in sufficient quantities, reallocation, etc.) from the US often held up work. Communications and travel were also a problem. The Army Corps of Engineers had no assigned transportation and had to rely on available military transport, scheduled and/or chartered commercial transport, and the outright begging of rides from all and sundry.

Recently established radiotelephone communications within Alaska and with headquarters in Seattle were primitive at best, and delays of several days duration before a usable connection could be established were common. Design and other questions had to be cleared through Seattle, and it was 1942 before any significant authority was granted to Alaska-based officers to make decisions regarding non-standard requirements. As an example of the difficulties engendered, the Fort Richardson Bachelor Officers’ Quarters (BOQ) could not be built within statutory cost limits using the standard design plans for such facilities. There was a delay while alterations in design were requested from Seattle, a further delay when the request was initially denied and had to be resubmitted and an additional delay when, upon approval of the change in standard design, the work on new plans was left to a firm of Seattle architects. Standard design and headquarters-approved plans also called for water towers in line with the runway approach at Elmendorf and aqua systems for fuel storage tanks at Elmendorf and Ladd which were unsuited to subarctic conditions.

The initial construction in Alaska at Ladd Field, Fort Richardson, Kodiak, Sitka, and Dutch Harbor involved permanent and semi-permanent structures such as standard-design Married Officers’ Quarters, BOQs, NCO apartments, hospitals, theaters, laundries, and warehouses. While the military had attempted to standardize structure types since the late nineteenth century, the modern history of such structures dates to World War I. The QM Corps Construction Division developed to Series 600 structure in response to the need to house recruits during training. The result was a wood frame building with board and batten siding resting on wooden piers. It was without plumbing and heated with wood-burning stoves. Between the wars, the plans were upgraded, but it was only when the Public Works Administration needed quick housing for relief project participants that the new Series 700 structure was developed. The new structures were built using new lumber sizes, 7 had larger rooms, improved sanitation (usually indoor) and heating, termite shields, and were built on concrete piers. The CCC building was a reusable off-shoot of the Series 700 type.

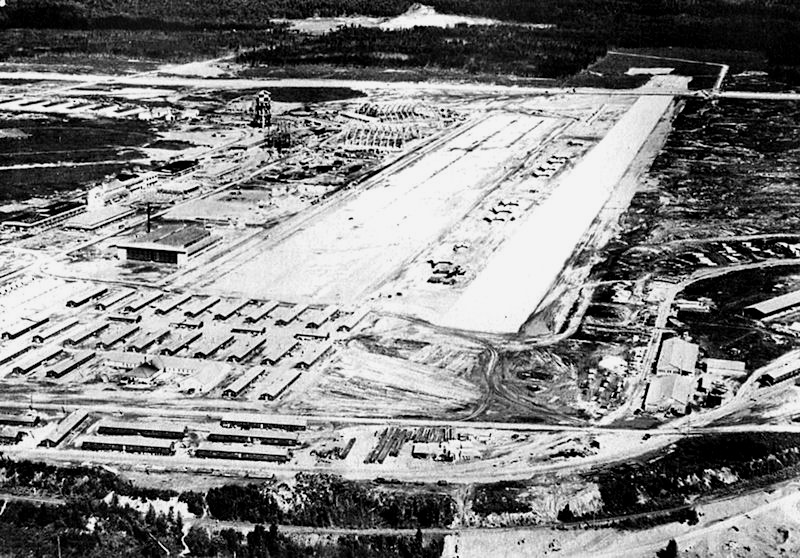

While Series 700 structures were being installed in 1940, an improved Series 800 version was being designed, although it would only be ready beginning in 1942, and would not be used in Alaska (Henry and Henry 1982). Construction was elaborate and expensive in terms of materials, skilled labor, and time to erect, and was suited to stateside, peacetime installations. Time, materials, and skilled labor were all at a premium, and after Pearl Harbor, such permanent construction was superceded by less costly types of facilities. In addition to the lack of suitability of structure types, base design with regular layout and high-density structures, as per the accepted stateside pattern, did not allow for dispersal or camouflage, making the facilities indefensible potential war zone targets (Bush 1944). The standardized base layouts, prescribed by the ACOE Engineering Manual, were designed to minimize infrastructure (roads and utilities) and land use as much as was consistent with fire safety and traffic patterns. Buildings were wedged into blocks with intervening firebreaks. A grid pattern was specified to minimize internal travel time and distance, resulting in closely packed arrangements of buildings. Between October 1940 and May 1942, planners worked to reduce the length of roads needed to serve standard layouts by 44 percent in the interests of the economy.

While Series 700 structures were being installed in 1940, an improved Series 800 version was being designed, although it would only be ready beginning in 1942, and would not be used in Alaska (Henry and Henry 1982). Construction was elaborate and expensive in terms of materials, skilled labor, and time to erect, and was suited to stateside, peacetime installations. Time, materials, and skilled labor were all at a premium, and after Pearl Harbor, such permanent construction was superceded by less costly types of facilities. In addition to the lack of suitability of structure types, base design with regular layout and high-density structures, as per the accepted stateside pattern, did not allow for dispersal or camouflage, making the facilities indefensible potential war zone targets (Bush 1944). The standardized base layouts, prescribed by the ACOE Engineering Manual, were designed to minimize infrastructure (roads and utilities) and land use as much as was consistent with fire safety and traffic patterns. Buildings were wedged into blocks with intervening firebreaks. A grid pattern was specified to minimize internal travel time and distance, resulting in closely packed arrangements of buildings. Between October 1940 and May 1942, planners worked to reduce the length of roads needed to serve standard layouts by 44 percent in the interests of the economy.

As Bush states, the primary reason for construction in Alaska was to establish an offensive or defensive system of airfields. In 1939, there were only four developed civil airfields in Alaska (Fairbanks, Anchorage, Juneau, and Nome) and these were usable only on a seasonal basis. They were supplemented by perhaps 100 makeshift bush landing strips which were privately constructed and maintained.

In July 1939, the Civil Aviation Administration (CAA) started an emergency program of airfield construction. This program began fields at Summit, Talkeetna, Moses Point, and Yakataga, with radio installations at Nome, Ruby, Fairbanks, Anchorage, Cordova, Yakutat, Juneau, and Ketchikan; weather stations were set up at Moses Point, Summit, Talkeetna and Petersburg. However, it was not until August 1940, that the CAA was directed to begin planning airfields with military usage in mind. Surveys were made and sites selected in late 1941, with construction beginning at eleven of the sites: Nome, West Ruby/Galena, McGrath, Bethel, Big Delta, Northway, Gulkana, Cordova, Juneau, Naknek and Cold Bay.

In July 1939, the Civil Aviation Administration (CAA) started an emergency program of airfield construction. This program began fields at Summit, Talkeetna, Moses Point, and Yakataga, with radio installations at Nome, Ruby, Fairbanks, Anchorage, Cordova, Yakutat, Juneau, and Ketchikan; weather stations were set up at Moses Point, Summit, Talkeetna and Petersburg. However, it was not until August 1940, that the CAA was directed to begin planning airfields with military usage in mind. Surveys were made and sites selected in late 1941, with construction beginning at eleven of the sites: Nome, West Ruby/Galena, McGrath, Bethel, Big Delta, Northway, Gulkana, Cordova, Juneau, Naknek and Cold Bay.

The CAA also worked on facilities at Anchorage’s Merrill Field, Aniak, Farewell, Homer, Iliamna, Kenai, Minchumina, Nenana, Seward, Tanacross and Tanana. Other sites selected for CAA fields were Annette Island (Metlakahtla), Port Heiden, and Sand Point. While such work was sorely needed in Alaska, the undertaking we probably too ambitious. Siting was often haphazard. With sites surveyed in winter and or by air, actual ground conditions with features such as swamps prevented the completion of runways and necessitated relocation after much-wasted work, as at West Ruby. Siting sometimes failed to take into account obstacles along approach routes, as at Nome. The construction was sometimes of questionable quality, and the design was not suited to military usage, since the added weight of a military payload required a better-prepared surface and longer runways than the civilian aircraft for which the fields were initially planned.

Most of the Civil Air Administration fields which were incorporated into the military system required additional work by Corps of Engineers construction detachments, beginning in 1942, to bring them up to these standards. Of the CAA fields, only Cold Bay ultimately approached anything like a combat role although many of the fields in the interior were heavily used in the Northwest Air Transport and the ALSIB ferrying routes; other fields, particularly those in the Southeast and at Nome were anticipated to be used for combat when begun. Runways at Juneau and Cordova were completed by the CAA, as were all fields in the interior except Ladd (Quartermaster Corps and Army Corps of Engineers).

Airfield construction also provided the introduction to a series of cold-weather engineering problems. Basic functional design and layout were essentially similar to that of forward bases in the Lower 48 as well as to the various areas of the Territory, with the standard runway being 5000 feet in length and 250 ft. wide, with taxiways, hardstands, and revetments for access and storage. Local conditions imposed-a wide variety of specific modifications, usually based on the availability of equipment and materials. Again, the cold, which could reach -60 degrees F, was not the primary difficulty, though it amplified the problems of working in a frontier zone in wartime.

The preferred method of construction involved the stripping of muskeg – an uneven, spongy ground cover of bunch grass, sphagnum moss, standing pools, and little if any woody vegetation – to a solid base of bedrock or stable substrate. This could only be done with power equipment, which was in short supply, mostly unsuited to the task, could only handle limited amounts between dumping loads, and constantly run the risk of bogging down in the muck. Runways at Annette Island, for instance, required stripping to a depth of up to 18 feet. In areas with permafrost, a perpetually frozen substrate, steam-thawing, and hydraulic excavation techniques, often adapted from mining, were used to enable the material to be worked. Where permafrost was not a problem, drainage often was, necessitating elaborate drainage system construction. Where tidal proximity affected the water table and the stability of the substrate, control dams were necessary to maintain the surface tension of the field. Such constructions were used at Adak and Amchitka but were considered for use at Yakutat as early as 1940.

At Kodiak, the runways had to be blasted out of bedrock, but in most cases, considerable fill was required to even out the surface and/or to replace the stripped organic layers. At Shemya, 50 ft. of sand fill would be required for some sections of the runway. This in turn required quarrying and crushing operations, since commercial quarry material was seldom if ever available, as well as road building to transport the materials. Quarry run rock, gravel, volcanic ash, pumice and sand were utilized as fill. The latter materials were also used as surfacing at numerous airfields, especially in the Aleutians. Reinforced concrete runways were rare, and the frost heaving associated the subarctic and arctic climates meant that constant, extensive maintenance was required in addition to the heavy initial use of expensive, strategic materials.

At Kodiak, the runways had to be blasted out of bedrock, but in most cases, considerable fill was required to even out the surface and/or to replace the stripped organic layers. At Shemya, 50 ft. of sand fill would be required for some sections of the runway. This in turn required quarrying and crushing operations, since commercial quarry material was seldom if ever available, as well as road building to transport the materials. Quarry run rock, gravel, volcanic ash, pumice and sand were utilized as fill. The latter materials were also used as surfacing at numerous airfields, especially in the Aleutians. Reinforced concrete runways were rare, and the frost heaving associated the subarctic and arctic climates meant that constant, extensive maintenance was required in addition to the heavy initial use of expensive, strategic materials.

Bitumen and asphalt were also used, albeit rarely and sparingly. Steel runway matting was used as a substitute for conventional surfaces. Pierced steel planking (Marsden mat) was the most common type, with bar-and-rod type being used for taxiways and hardstands. These surfaces, while making profligate use of strategic materials, were quick and easy to install and provided an acceptable surface when laid over a properly prepared footing. They did have a tendency to bounce the aircraft on landing, ripple under the weight of heavier planes, and roll up in high winds. Steel matting was not available until February 1942 and hence was used primarily at forward bases in the Aleutian chain. The fourth and fifth goals of the Alaska defense plan – garrisoning the Army airfields and Navy bases with combat troops for the protection of those sites also required facilities, and attempts to prepare them began with the recommendations of the treenslade Board in May 1941. The scopes of work presented by the Hepburn Board for Sitka, Kodiak and Dutch Harbor were expanded to include more naval facilities at these sites, and Army garrison facilities, to be constructed by the civilian Navy contractor, were added, as were subsidiary Naval Section Bases (NSB) at Sand Point, Port Althorp and Port Armstrong. The contemplated expenditure for all these projects rose from $15 million of the Hepburn Report to $165 million.

The Army, while agreeing to share bases and facilities with the Navy, gave their portion of each such tenancy facility its own designation when construction began early in 1941. Sitka, became Fort Ray (named for Gen Patrick H. Ray) for the period 1941-1944, a Coastal Fort first established in 1941 on Japonski Island, Sitka, Sitka Borough, Alaska. Fort Ray was abandoned in 1944. Kodiak, became Fort Greely (named for Gen Adolphus Greely), for the period 1941-1944, a Coastal Fort first established in 1941 on Kodiak Island, Kodiak Island Borough, Alaska. Fort Greely was abandoned in 1944. Dutch Harbor, which became Fort Mears (named for Col Frederick Mears) for the period 1941-1945, was a US Army Coastal Fort first established in 1941 in Dutch Harbor, Aleutians West Census Area, Alaska. Fort Mears was abandoned in 1945. In addition, the Army would ultimately grant a Fort designation to individual battery installations. Hence, Fort Richardson, with a single name, encompassed over 40.000 acres, while the Army facilities at Dutch Harbor included almost two dozen named outposts with several different forts, some consisting of little more than an isolated battery or observation outpost. The Navy had not set aside areas for the Army in the initial planning stage, so in most cases, there was little or no suitable land available for Army facilities. When Army facilities were shoehorned in, it served to complicate the problems of dispersal, camouflage, and defensibility, leaving crowded masses of barracks and other structures.

The Army, while agreeing to share bases and facilities with the Navy, gave their portion of each such tenancy facility its own designation when construction began early in 1941. Sitka, became Fort Ray (named for Gen Patrick H. Ray) for the period 1941-1944, a Coastal Fort first established in 1941 on Japonski Island, Sitka, Sitka Borough, Alaska. Fort Ray was abandoned in 1944. Kodiak, became Fort Greely (named for Gen Adolphus Greely), for the period 1941-1944, a Coastal Fort first established in 1941 on Kodiak Island, Kodiak Island Borough, Alaska. Fort Greely was abandoned in 1944. Dutch Harbor, which became Fort Mears (named for Col Frederick Mears) for the period 1941-1945, was a US Army Coastal Fort first established in 1941 in Dutch Harbor, Aleutians West Census Area, Alaska. Fort Mears was abandoned in 1945. In addition, the Army would ultimately grant a Fort designation to individual battery installations. Hence, Fort Richardson, with a single name, encompassed over 40.000 acres, while the Army facilities at Dutch Harbor included almost two dozen named outposts with several different forts, some consisting of little more than an isolated battery or observation outpost. The Navy had not set aside areas for the Army in the initial planning stage, so in most cases, there was little or no suitable land available for Army facilities. When Army facilities were shoehorned in, it served to complicate the problems of dispersal, camouflage, and defensibility, leaving crowded masses of barracks and other structures.

Few today understand the immensity of the task of taming a country like Alaska. Towards the end of the 30s, there was not yet a road network worthy of the name nor yet since the wild nature in the extreme and untouched of this part of the world was doing everything possible to combat the human presence. Only the natives were able to live there. This said in order to underline the incredible task that the men of the Corps of Engineers faced in successfully building bases for the Army, Army Air Force and Navy

At Sitka, the Navy facilities covered the prime site at Japonski Island, and Army facilities had to be built on adjacent small islands. To connect the various parts of the base and allow access, causeways were built between nine separate islands. Problems with a lack of materials for the mandated standard Quartermaster plan Theater of Operations (T/0) structures caused extensive delays. At Kodiak, there was a similar lack of room at the main naval area in Womens Bay, leaving the Army facilities to be built, under protest of the Army, north of the Buskin River on the swampy ground at some remove from the base they were designed to protect. The sharing of facilities also proved easier to plan than to execute: the Army Air Corps facilities were at the Navy field, but were strictly separate, leading to exactly the duplication that sharing was supposed to eliminate.

At Dutch Harbor, the ranks of Series 700 structures crammed into surplus land in the Margaret Bay area not only became targets for the Japanese but also failed to provide adequate housing for Army operations, leading the Army to expand up the Unalaska Valley behind the town of Unalaska, across an unbridged channel from the main naval base.

At Dutch Harbor, the ranks of Series 700 structures crammed into surplus land in the Margaret Bay area not only became targets for the Japanese but also failed to provide adequate housing for Army operations, leading the Army to expand up the Unalaska Valley behind the town of Unalaska, across an unbridged channel from the main naval base.

The difficulties of coordination between the services on the ground were symptomatic of the attitudes which kept the Army and Navy at odds during much of the war. Prior to the war, Alaska was under the jurisdiction of the Thirteenth Naval District, headquartered in Seattle, which in turn was under the command of the Twelfth Naval District (San Fransisco), with responsibility for what was called the Pacific Naval Coastal Frontier.

The difficulties of coordination between the services on the ground were symptomatic of the attitudes which kept the Army and Navy at odds during much of the war. Prior to the war, Alaska was under the jurisdiction of the Thirteenth Naval District, headquartered in Seattle, which in turn was under the command of the Twelfth Naval District (San Fransisco), with responsibility for what was called the Pacific Naval Coastal Frontier.

In 1940, a separate Alaska Sector (ComAlSec) was established, under the command of Capt Ralph C. Parker, with headquarters at Kodiak and the gunboat Charleston as his flagship. The District Coast Guard, headquartered at Ketchikan, was ordered to operate under ComAlSec. One of Parker’s duties was to recommend sites for the establishment of additional naval facilities, but with the exception of the Greenslade additions, Parker’s recommendations were ignored. Until July 1940, Alaska was within the Ninth Corps Area, which was commanded by Gen John L. DeWitt of the Fourth Army. Given the projected rapid and extensive military development in Alaska, it was decided that an on-site special commander was needed, and DeWitt proposed his chief of staff, Col Simon Bolivar Buckner. Buckner was appointed July 9, 1940, arriving in the Territory July 22, 1940. The garrison was redesignated the Alaska Defense Force, and Buckner was promoted to brigadier general in September.

In 1940, a separate Alaska Sector (ComAlSec) was established, under the command of Capt Ralph C. Parker, with headquarters at Kodiak and the gunboat Charleston as his flagship. The District Coast Guard, headquartered at Ketchikan, was ordered to operate under ComAlSec. One of Parker’s duties was to recommend sites for the establishment of additional naval facilities, but with the exception of the Greenslade additions, Parker’s recommendations were ignored. Until July 1940, Alaska was within the Ninth Corps Area, which was commanded by Gen John L. DeWitt of the Fourth Army. Given the projected rapid and extensive military development in Alaska, it was decided that an on-site special commander was needed, and DeWitt proposed his chief of staff, Col Simon Bolivar Buckner. Buckner was appointed July 9, 1940, arriving in the Territory July 22, 1940. The garrison was redesignated the Alaska Defense Force, and Buckner was promoted to brigadier general in September.