Document Sources:

Internet, Wikipedia, German News Papers

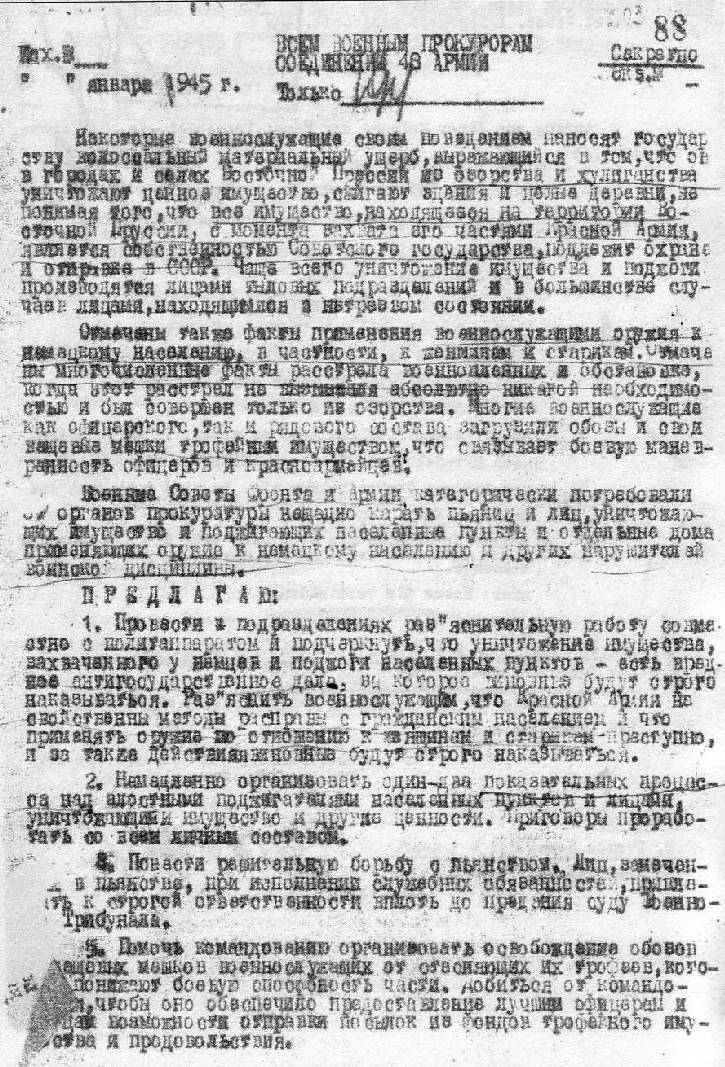

The Soviet executive order to military prosecutors of the 48th Army for taking legal measures against lootings, burning of houses and killing of civilians by the Red Army soldiers. The original text reads as follows:

The Soviet executive order to military prosecutors of the 48th Army for taking legal measures against lootings, burning of houses and killing of civilians by the Red Army soldiers. The original text reads as follows:

Полный текст: Некоторые военнослужащие своим поведением наносят государству колоссальным материальный ущерб, выражающийся в том, что в городах и сёлах Восточной Пруссии из озорства и хулиганства уничтожают ценное имущиство, сжигают здания и целые деревни, не понимая, что всё имущество, находящееся на территории Восточной Пруссии, с момента захвата его частями Красной Армии, является собственностью Советского государства, подлежит охране и отправке в СССР. Чаще всего уничтожение имущества и поджоги проводятся лицами тыловых подразделений и в большинстве случаев лицами, находящимися в нетрезвом состоянии. Отмечены также факты применения военнослужащими оружия к немецкому населению, в частности, к женщинам и старикам. Отмечены многочисленные факты расстрела в обстановке, когда этот расстрел не был вызван абсолютно никакой необходимостью и был совершён только из озорства. Многие военнослужащие как офицерского, так и рядового состава загрузили обозы и свои вещевые мешки трофейным имуществом, что связывает боевую маневренность офицеров и красноармейцев. Военные Советы Фронта и Армии категорически потребовали от органов прокуратуры нещадно карать пьяниц и лиц, уничтожающих имущество и поджигающих населённые пункты и отдельные дома, применяющих оружие к немецкому населению, и других нарушителей воинскох дисциплины. Предлагаю: Провести в подразделениях разъяснительную работу совместно с политаппаратом и подчеркнуть, что уничтожение имущества, захваченного у немцев, и поджёги населённых пунктов — есть вредное антигосударственное дело, за которое виновные будут строго наказываться. Разъяснить военнослужащим, что Красной Армии несвойственны методы расправы с гражданским населением и что применять оружие по отношению к женщинам и старикам преступно, и за такие действия виновные будут строго наказываться. Немедленно организовать один-два процесса над яростными поджигателями населённых пунктов и лицами, уничтожающими имущество и другие ценности. Приговоры проработать со всем личным составом. Провести решительную борьбу с пьянством. Лиц, замеченных в пьянстве при исполнении служебных обязанностей, привлекать к строгой ответственности вплоть до придания суду Военного Трибунала. Помочь командному составу организовать освобождение обозов и вещевых мешков военнослужащих от стесняющих их трофеев, которые понижают боевую способность части. Добиться от командования, чтобы оно обеспечило предоставление лучшим офицерам и бойцам возможности отправки посылок из фондов трофейного имущества и продовольствия.

(Translation) Some servicemen have caused enormous material damage by their behavior, because they destroy valuable property in the cities and villages of East Prussia, burning down  buildings and whole villages which belong to the Soviet state now… Furthermore, cases were determined where army members used weapons against the German civilian population, particularly against women and the elderly. Numerous cases were determined where prisoners of war were shot under circumstances in which shooting was not necessary but came only from bad will.

buildings and whole villages which belong to the Soviet state now… Furthermore, cases were determined where army members used weapons against the German civilian population, particularly against women and the elderly. Numerous cases were determined where prisoners of war were shot under circumstances in which shooting was not necessary but came only from bad will.

The order goes on to specify measures against such occurrences, defining the occurrences as unjustified and inadmissible. Specifically, the order proposes to conduct one-two demonstrative punishments of Soviet soldiers accused of war crimes and to initiate a struggle against intemperance in the Red Army.

NEMMERSDORF 1944

According to Frau Gerda Meczulat who, on October 21, 1944, was heading in one bomb shelter with other civilians at that time, elements of the 2/25 Soviet Guards Tank Corps of the 11th Guards Army (Galitzki) moved near the village of Nemmersdorf on the frontier of East Prussia, Germany (today, Mayakovskoye, Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia), capturing the nearby Angerapp bridge to establish a bridgehead on the western bank of the Rominte River. Several attempts to counter-attack were launched by the Germans, some of them being supported by the Lufwaffe. During one of the Luftwaffe attacks, some Soviet troops were ousted and fled into a bomb shelter built and occupied by 14 civilians, men and women, all residents of Nemmersdorf. Frau Meczulat reported that some kind of Soviet officers came in and immediately started to gun down the civilians, seriously wounding, but not killing, Meczulat. These soldiers used the shelter for their own purpose while other troops set up defensive positions within the village itself. During the following night, the Soviet 25 Tank Brigade was ordered to retreat back across the river and take defensive positions along the Rominte.

German troops returned to Nemmersdorf on October 23, and found a large number of civilians killed. German soldier Günter Koschorrek’s diary revealed his finding of an old man whose throat had been drilled through with a pitchfork so that his entire body was hanging on a barn door. It is impossible for me to describe all the terrible sights we have witnessed in Nemmersdorf. Other witnesses spoke of refugees being trampled by Soviet tanks and civilians mowed down by machine gun fire at the bridge leading out of town. On July 5, 1946, the former chief of staff of the German 4.Army, Maj Gen Erich Dethleffsen testified before an American tribunal in Neu-Ulm, Germany, stating:

When in October 1944, Russian units temporarily entered the little village of Nemmersdorf, they tortured the civilians, specifically they nailed them to barn doors, and then shot them. A large number of women were raped and then shot. During this massacre, the Russian soldiers also shot some fifty French prisoners of war. Within forty-eight hours the Germans re-occupied the area.

German authorities organized an international commission to investigate this massacre, headed by Estonian Hjalmar Mäe and other representatives of neutral countries, such as Francoist Spain, Sweden and Switzerland. The commission heard the report from a medical commission. It reported that all the dead females had been raped (they ranged in age from 8 to 84). The Nazi Propaganda Ministry (separately) used the Völkischer Beobachter and the cinema news series Wochenschau to accuse the Soviet Army of having killed dozens of civilians at Nemmersdorf and having summarily executed about 50 French and Belgian noncombatant POWs, who had been ordered to take care of thoroughbred horses but had been blocked by the bridge. The civilians were allegedly killed by blows with shovels or gun butts.

German authorities organized an international commission to investigate this massacre, headed by Estonian Hjalmar Mäe and other representatives of neutral countries, such as Francoist Spain, Sweden and Switzerland. The commission heard the report from a medical commission. It reported that all the dead females had been raped (they ranged in age from 8 to 84). The Nazi Propaganda Ministry (separately) used the Völkischer Beobachter and the cinema news series Wochenschau to accuse the Soviet Army of having killed dozens of civilians at Nemmersdorf and having summarily executed about 50 French and Belgian noncombatant POWs, who had been ordered to take care of thoroughbred horses but had been blocked by the bridge. The civilians were allegedly killed by blows with shovels or gun butts.

In 1953, Karl Potrek of Königsberg, CO of one Volkssturm Company p^resent when the German Army tokk back the village testified:

In one farmyard stood a cart, to which more naked women were nailed through their hands in a cruciform position. Near a large inn, the ‘Roter Krug’, stood a barn and to each of its two doors a naked woman was nailed through the hands, in a crucified posture. In the dwellings we found a total of 72 women, including children, and one old man, 74, all dead. Some babies had their heads bashed in.

Of course, at the time, the Nazi Propaganda Ministry disseminated a graphic description of the events in order to fanaticise German soldiers.

On the home front, civilians reacted immediately with an increase in the number of volunteers joining the Volkssturm while a large number of civilians responded with panic, and started to leave the area en masse. To many Germans, Nemmersdorf became a symbol of war crimes committed by the Red Army, and an example of the worst behavior in Eastern Germany. Marion Gräfin Dönhoff, the post-war co-publisher of the weekly news paper Die Zeit, at the time of the reports lived in the village of Quittainen (Kwitany) in western East Prussia, near Preussisch Holland (Pasłęk). She wrote in 1962 that:

On the home front, civilians reacted immediately with an increase in the number of volunteers joining the Volkssturm while a large number of civilians responded with panic, and started to leave the area en masse. To many Germans, Nemmersdorf became a symbol of war crimes committed by the Red Army, and an example of the worst behavior in Eastern Germany. Marion Gräfin Dönhoff, the post-war co-publisher of the weekly news paper Die Zeit, at the time of the reports lived in the village of Quittainen (Kwitany) in western East Prussia, near Preussisch Holland (Pasłęk). She wrote in 1962 that:

In those years one was so accustomed to everything that was officially published or reported being lies that at first I took the pictures from Nemmersdorf to be falsified. Later, however, it turned out that that was not the case.

According to Wikipedia, in 1991, and the fall of the Soviet Union, new sources became available and the dominant view among scholars became that the massacre was embellished, and actually exploited, by Goebbels in an attempt to stir up civilian resistance to the advancing Soviet Army. Bernhard Fisch, in his book, Nemmersdorf, October 1944. What actually happened in East Prussia concluded that liberties were taken with at least some of the photographs; that some victims on the photographs were from other East Prussian villages, and that the notorious crucifixion barn doors were not even in Nemmersdorf.

Another writer, Joachim Reisch, claimed to have personally been at the scene of the bridge when the event was supposed to have occurred. He has said that the Soviet Brigade was on the bridge for less than four hours.

Sir Ian Kershaw is among those historians who believe that the Soviet forces committed a massacre at Nemmersdorf, although details and numbers are disputed. The German Federal Archives (Bundesarchiv) contain many contemporary reports and photographs by officials of Nazi Germany of the victims of the Nemmersdorf massacre. It holds evidence of other Soviet massacres in East Prussia, notably Metgethen. In the late 20th century, Alfred de Zayas interviewed numerous German soldiers and officers who had been in the Nemmersdorf area in October 1944, to learn what they saw. He also interviewed Belgian and French POWs who had been in the area and fled with German civilians before the Russian advance. De Zayas incorporated these sources into two of his own books, Nemesis at Potsdam and A Terrible Revenge.