In February 1941, the area would be designated the Alaska Defense Command (ADC), with headquarters at Fort Richardson. The ADC Air Force was established in October 1941. By 1941, there was an argument over whether to make Alaska a separate department.

Gen Carl Tooey Spaatz (USAAF) argued that Alaska was sufficiently geographically, strategically and tactically separate to warrant independent command, while DeWitt, argued that the need for coordination of effort meant that it should stay under his command.

DeWitt’s viewpoint ultimately prevailed.

In Alaska, Buckner and Parker became personal friends who worked well together, but the differences in official service policies regarding responsibilities and the lack of success in gaining priority access to scarce resources stymied the development of a lasting working relationship between the services. Most of the planning done in these early days was of an ad hoc nature, an attempt in the absence of concrete support from up the chain of command to accomplish a mission and establish workable understandings.

In August 1941, the USCG, the ADC, and ComAlSec formulated a joint plan calling for long-range air reconnaissance, local defense against small-scale raids, convoying for seaborne shipping, and cooperative organization of facilities for mutual use and benefit.

The Navy was unable to get necessary shipping for patrol work, the Army was unable to get aircraft necessary for patrolling and for protection of the new bases, and both were constantly turned down on recommendations for physical expansion in men and materiel and on all demands for a change from strict defense to a growing offense. Internally, there was a lack of agreement as to how best to defend Alaska aside from the strategic Army-Navy arguments about respective service roles. One position held that there should be a mobile striking force located at the time center of Alaska (i.e., at Fort Richardson) which could be rushed to the site of enemy action.

This would centralize and concentrate necessary construction and manning needs while limiting the number of far-flung, vulnerable posts to be maintained. The main argument against this plan was that transport and logistic capabilities were inadequate to effectively support it. The alternative was to establish strategic strong points to control the entire area, which its opponents argued was to invite destruction piecemeal. The latter format was never officially accepted but did form the accepted basis for Alaskan strategy throughout the war, as seen by the gradual expansion of bases and shift from east to west.

The first reinforcements to reach Alaska consisted of 780 soldiers who arrived at Fort Richardson in late June 1940. In August, Maj Everett S. Davis, senior representative and advisor from the Army Air Corps arrived in Anchorage in a B-10B Bomber, the first military combat aircraft to reach Alaska. This aircraft roster was augmented by the 18th Pursuit Squadron with 20 crated Curtiss P-36 Hawk in February 1941. In March, the 73rd Bomber Squadron and the 36th Bomber Squadron, with a complement of 14 Boeing B-18As in March. All the aircraft were obsolete types unsuited to combat, especially in Alaska. By November 1941, only six of the B-18s would be flying. The Navy air forces were even less of the present, with only two observation planes, a Vought OS2U Kingfisher at Kodiak and a Grumman J2F Duck at Sitka.

There were few military personnel, though their numbers were growing rapidly.

The low initial base meant that percentage increments were more impressive on paper than on the ground. The 1940 census listed a population for Alaska of 76.000 of whom about 1000 were military personnel. By the beginning of 1941, there were about 3000 troops in the Territory. Between June and October 1941, Alaska Defense Command forces grew from 7263 to 21.565, while the Navy had 180 at Sitka, 300 at Kodiak, and 67 at Dutch Harbor, for a total naval strength of only about 550 and a total military strength of about 22.000. The assignment of forces left Sitka with 2020, Kodiak with 5835, and Dutch Harbor with 5425. To augment these forces, the War Department set to work in mid-1940 to establish the Alaskan National Guard, consisting of non-draft age or deferred draft status men. The 297th Infantry Battalion (Alaska Scouts) was authorized. Activated in September 1941, it was sent to the US for training. Some units actually served in Alaska during the war. The formation of the National Guard was followed by the organization of the Alaska Territorial Guard (ATG) after Pearl Harbor in January, 1942. Buckner suggested the establishment of a body of 888 irregulars, and a home guard was authorized for nonstrategic defense, with regulars being left to protect strategic facilities and routes.

Governor Gruening and his military attache, Capt Carl Scheibner, were officially responsible for the ATG. The actual organization was accomplished by Scheibner and Maj Marvin R. ‘Muktuk’ Marston, a Lawrence of Arabia type figure transplanted to the North. Marston traveled over northern and western Alaska recruiting the Eskimos as scouts and guerilla cadres. He passed out surplus 1917 Enfield rifles and ammunition, arranged for the construction of armories (kashims, which served as local community centers as well), and made some supplies available. Indirectly, he provided a basis for later political organization among the Eskimo, championing Native rights at a time when such was unfashionable. Although the ATG never served in combat, it did provide scouting and intelligence services, rescued downed fliers, and built trails. After WW II, the ATG formed the nucleus of the regular National Guard.

Governor Gruening and his military attache, Capt Carl Scheibner, were officially responsible for the ATG. The actual organization was accomplished by Scheibner and Maj Marvin R. ‘Muktuk’ Marston, a Lawrence of Arabia type figure transplanted to the North. Marston traveled over northern and western Alaska recruiting the Eskimos as scouts and guerilla cadres. He passed out surplus 1917 Enfield rifles and ammunition, arranged for the construction of armories (kashims, which served as local community centers as well), and made some supplies available. Indirectly, he provided a basis for later political organization among the Eskimo, championing Native rights at a time when such was unfashionable. Although the ATG never served in combat, it did provide scouting and intelligence services, rescued downed fliers, and built trails. After WW II, the ATG formed the nucleus of the regular National Guard.

Another unit which played a role in Alaska was the Alaska Combat Intelligence Platoon or Alaska Scouts. Also known as Castner’s Cutthroats after Col Lawrence V. Castner, the intelligence officer for the ADC who founded the unit in November 1941. These men gathered combat intelligence and operated as commandos in most operations in the Aleutians as well as elsewhere in Alaska. The unit consisted of locals – Eskimos, Aleuts, Indians, Trappers, Sourdoughs and Fishermen – with special knowledge of Alaska and survival skills. The unit operated independently, with the men being allowed to choose their own equipment and dress.

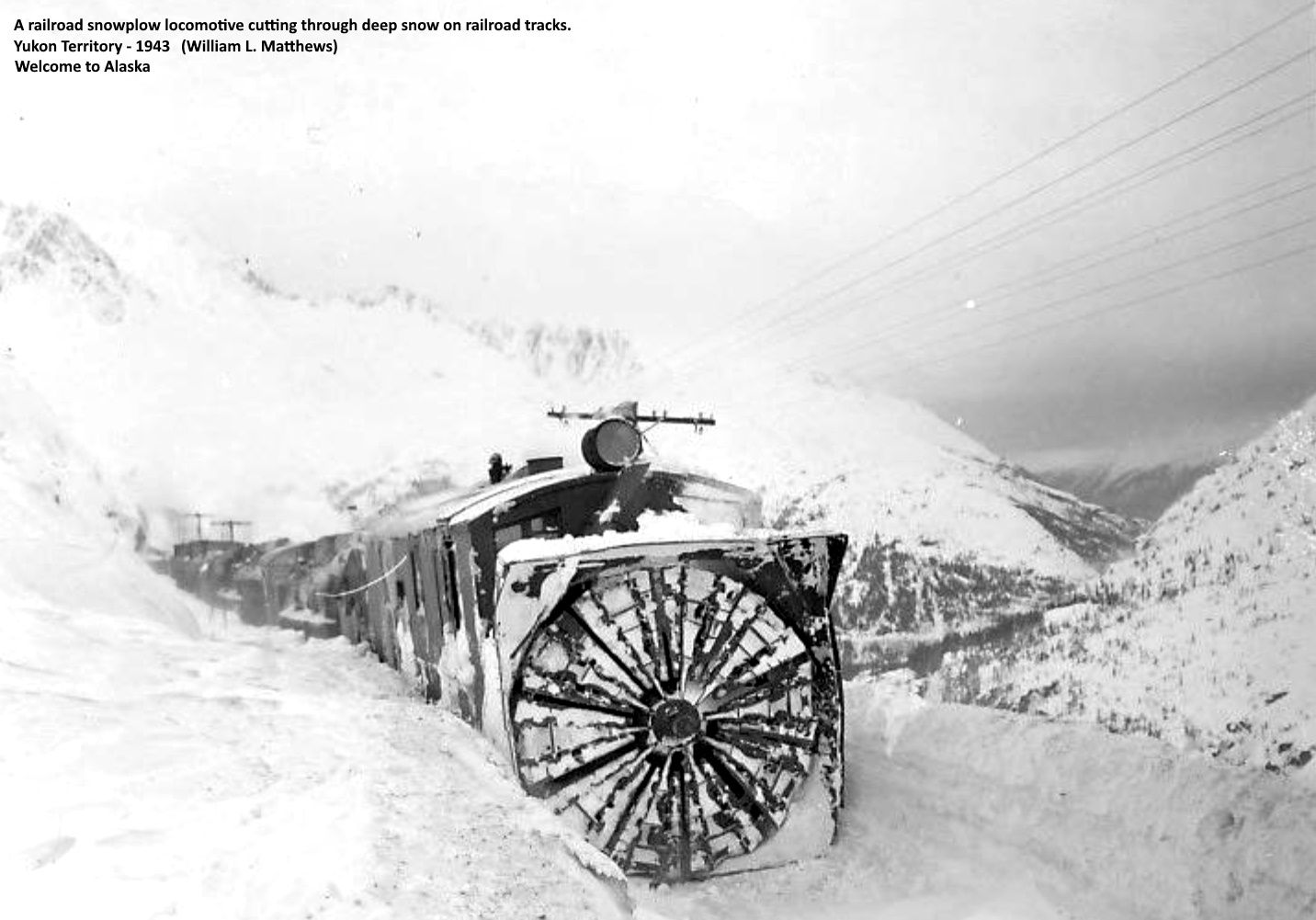

One of the most intractable problems with the development and defense of Alaska lay in its vast size and inaccessibility. In 1940, Alaska had a nominal 10.171 miles of roads and trails, only 2212 miles of which were suitable for vehicular use, and only 370 miles of which represented a major artery, the Richardson Highway. During the war, the Army would build 1129 miles of roads exclusive of the ALCAN Highway, most of them pioneer, or unimproved roads. The main internal road built by the military during the war besides the ALCAN was the Glenn Highway, which connected the Anchorage area with the main coastal-interior road, the Richardson Highway. This road was opened in October 1942. Roads were a relatively inefficient means of moving personnel and materials in Alaska. The primary land-based transport route was the Alaska Railroad. Early in 1941, it was recognized that this route was inadequate, especially the segment connecting the port of Seward, which was frozen in part of the year, with the proposed main base at Anchorage.

The route was tortuous and vulnerable to potential enemy interdiction by air attack or sabotage. Other potential routes were considered, with a route linking the year-round ice-free Passage Canal site of Whittier with the main line at Portage, near the head of Turnagain Arm. This route would require major tunneling under glaciated mountains. A contract was let with the West Construction Company of Seattle in June 1941, with construction beginning that summer. Two tunnels, one 5000 and the other 14.000 feet long were blasted, with the holing-through occurring in November 1942, six months ahead of schedule despite various contractor and supply problems. Port facilities were constructed at Whittier, and the line provided a critically important supply point from spring 1943, onward. The cost was some $11 million. Other railroad work involved reconstructing existing and/or abandoned lines for supply, as was the case with the White Pass-Yukon Railroad, linking Skagway and Whitehorse, Yukon Territories (October 1942), which was used to supply materials for the ALCAN Highway and CANOL projects in the interior of Canada. Similar work took place with the Copper River – Northwestern at Cordova, the Yakutat & Southern at Yakutat, and the Seward Peninsula Railroad at Nome for accessing and serving various bases. Internal spurs and switching were also built to service Ladd Field and Fort Richardson. With the exception of the main line of Alaska Railroad and the White Pass and Yukon, these other lines were minor in terms of trackage and importance.

One problem experienced in running the railroads in Alaska was that many experienced personnel left for other jobs or were drafted, leaving the operators with a dearth of qualified personnel. Army Railroad Operating Battalions (the 741st, 713th, and 770th) were brought in and provided the core of operating personnel for the duration of the war.

The increased demands on the often poorly constructed rail lines, with their antiquated equipment (the initial authorization for the Alaska Railroad stipulated that it would use rolling stock from the Panama Canal Railway), also caused operating problems, which required constant repair and improvisation throughout the war.

Ocean shipping was the primary means of access and supply to Alaska at the beginning of World War II. Ninety percent of all goods, including subsistence, were imported from the outside during the prewar period, with virtually all coming in by ship. At the beginning of the war, there were eight commercial shipping lines serving Alaska, using Seattle as a Port of Entry (POE). The military took over the operation of most of these firms, either through lease or direct regulation. The Army leased from private and corporate owners 53 seagoing tugs, two shallow-draft tugs, 18 power barges, two schooners and 101 scows for use in Alaska during the war, and in early 1943, operated a total of 190 watercraft of various types. The Army also operated three sternwheelers as river transport on the Yukon and Kuskokwim Rivers for internal supply.

Shipping was as difficult as anything else in Alaska. The route ran up the west coast of the US and Canada, which was open to potential enemy action by submarine and/or surface craft so that what few naval vessels were available were often tied up in convoy duty. The Inside Passage formed a partially sheltered route along the Panhandle but was difficult to navigate and only extended part of the way.

The Gulf of Alaska was considered particularly vulnerable. Potential ports had numerous drawbacks as well. Seward was iced in several months each year and relied on the problematical link with the interior via the Alaska Railroad.

Anchorage was also iced in and had to contend with the 30-foot tides of Cook Inlet. Cordova and Valdez were away from the main buildup areas and lacked the means for transshipping goods brought into their ports to the areas of need. With these difficulties, the need for the Whittier cutoff with its ice-free port becomes more understandable. The Bering Sea locations were even more of a problem, since they were usually closed eight months out of the year and even when open required lightering of goods since there were few sites (none developed) with natural harbors. The shallow continental shelf extended several miles into the Bering Sea at Nome and several other sites. River transport was even less effective since the major river systems of the interior were often frozen nine months of the year. The lack of facilities was also a hardship, reducing the military to using out-of-repair and inadequate cannery docks. At the beginning of the war, there were docks at Anchorage, Bethel, Cordova, Juneau, Ketchikan, Kodiak, Nome, Petersburg, Seward, Sitka, Skagway, Valdez, Wrangell and Yakutat; the major installation at Cold Bay could only be served by a fishery dock at King Cove, and the only port facilities in the Aleutians were docks at Dutch Harbor, Akutan, and Kanaga. Still, even after the construction of the ALCAN Highway and the opening of the Northwest staging route, sea transport was far and away the most significant means of supply, both military and civilian, for Alaska.

Given the isolation of the Territory and its lack of development at the beginning of the war, the military found that it had to build many facilities from scratch which in the normal course of events would have been provided by some surrounding civilian entities or purchased on the market. Initially, utilities like power, light, heat, water, and sewage, were often required where civil provision was inadequate or entirely lacking. In the early days of the buildup, steam-generating power plants were constructed at Ladd Field and at Fort Richardson, although later facilities relied on 25 to 1000KW diesel generators. Low voltage was to be a constant problem with brownouts and power failures occurring frequently. Electric power was to be used primarily for operating equipment and secondarily for light. The heat was a separate problem. Again, only Ladd and Richardson had general steam heat plants, though central oil-fired steam heat plants were installed for some facilities in individual buildings, such as hospitals and laundries. Most personnel had to make do with a variety of coal, wood, and oil space heaters which generally worked poorly in terms of heat radiation, making the immediate vicinity unbearable while leaving areas away from the device essentially unheated. Atomizing oil burners were used for heating large barracks and for cookstoves (other cook stoves were electrically powered). Individual small structures were heated with coal-fired Sibley stoves (a relic of the nineteenth century cavalry frontier) and pot-type oil burners. The latter used a special blend of oil concocted for use in frigid environments. This fuel had a pour point to -40 degrees and a cloud point of -30 degrees. The use of any other grade of oil resulted in a 30% reduction in efficiency and a high incidence of flue fires and flare-ups. The low roofline and chimney profile on many structures coupled with the high winds led to blowback fires. Firefighting services were also virtually nonexistent, and most military firefighting was geared toward aircraft crash damage control rather than facilities protection.