Authorized in 1900, intra-state telegraphic communication was achieved by 1903, with undersea cable connections being completed to Seattle by 1904. The Signal Corps, which was to form the nucleus of the military presence in Alaska prior to World War II, operated the Washington-Alaska Military Cable and Telegraph System (WAMCATS) which handled military and civilian messages and would later evolve into the Alaska Communications System (ACS). The distances and the harsh weather involved made maintenance of landlines infeasible, and advances in radio technology, fortunately, provided an alternative. A military communications network was proposed in 1907, with the Army establishing stations at Forts Gibbon, Egbert, and Davis and at Fairbanks and Circle in 1908. The Navy had radio and weather stations at Sitka (1907) and Cordova (1908) and, by 1909, there were commercial stations at Katalla, Juneau and Ketchikan operated by United Wireless. The Army system was expanded with stations at Wrangell, Petersburg, Kotlik (1910), and Nulato (1912), with the Navy adding facilities at Kodiak (Woody Island), Dutch Harbor, St Paul (1911), Unalga (1912).

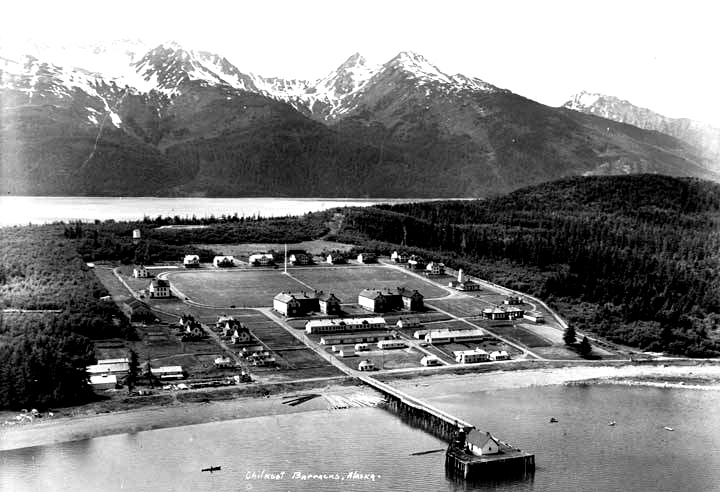

Alaska finally achieved territorial status with the second Organic Act of 1912, however, the restrictive terms of the act denied the legislature the power to regulate natural resource use, pass land laws, levy taxes and issue bonds, causing numerous headaches for civil authorities. The act did create the Alaska Railroad Commission to investigate the building of a railroad to the interior. The construction began in 1915, and although the 470-mile main line was not completed until 1923, the road represented the first federally-funded, owned and operated railroad in the US, showed a commitment to Alaska on the part of the federal government, and opened the interior via relatively efficient transportation. In 1912, exclusive of communications facilities, the Army maintained bases at Fort Davis, Nome area; at Fort St Michael, Norton Sound-Yukon Delta areas; at Fort Gibbon, Tanana area; at Fort Egbert, Eagle area; at Fort Liscum, Valdez area; and at Fort Seward (later Chilkoot Barracks, at Haines). In 1915, the Army had an authorized strength of a regiment (1900 men) in Alaska, although the actual strength was only 958, consisting mainly of Signal Corps technicians who operated 53 offices and 10 radio stations. In 1912, the Navy closed its only non-communications facility at Sitka. Previously, the Navy had surveyed the Aleutians for potential operating base sites and in 1902 had recommended Dutch Harbor as a coaling station. This recommendation was changed to favor a base at Kiska in 1903, with lands being withdrawn by Executive Order in 1904.

Alaska finally achieved territorial status with the second Organic Act of 1912, however, the restrictive terms of the act denied the legislature the power to regulate natural resource use, pass land laws, levy taxes and issue bonds, causing numerous headaches for civil authorities. The act did create the Alaska Railroad Commission to investigate the building of a railroad to the interior. The construction began in 1915, and although the 470-mile main line was not completed until 1923, the road represented the first federally-funded, owned and operated railroad in the US, showed a commitment to Alaska on the part of the federal government, and opened the interior via relatively efficient transportation. In 1912, exclusive of communications facilities, the Army maintained bases at Fort Davis, Nome area; at Fort St Michael, Norton Sound-Yukon Delta areas; at Fort Gibbon, Tanana area; at Fort Egbert, Eagle area; at Fort Liscum, Valdez area; and at Fort Seward (later Chilkoot Barracks, at Haines). In 1915, the Army had an authorized strength of a regiment (1900 men) in Alaska, although the actual strength was only 958, consisting mainly of Signal Corps technicians who operated 53 offices and 10 radio stations. In 1912, the Navy closed its only non-communications facility at Sitka. Previously, the Navy had surveyed the Aleutians for potential operating base sites and in 1902 had recommended Dutch Harbor as a coaling station. This recommendation was changed to favor a base at Kiska in 1903, with lands being withdrawn by Executive Order in 1904.

However, military thinking changed, and the Aleutian base was considered too limited to fit strategic needs. The plan for a facility at Kiska was withdrawn in 1915. Morgan reports that naval construction was actually begun at Kiska in 1916, but that it did not proceed beyond driving pilings for a dock.

For a number of reasons, World War I drained population and resources from Alaska. Prior to US entry into the war, numerous Alaskans enlisted in the Canadian armed forces, and after US involvement, others were drafted. While few made it overseas, many left the Territory and failed to return. There were few military projects in Alaska during the war, and most Army activity consisted of guarding the newly begun railroad and communications facilities, while the Navy’s role involved patrolling fishing grounds and suppressing labor unrest in the canneries. The Navy did initiate coal mining tests from 1918 through 1922 in the Chickaloon area to investigate the viability of producing a fuel reserve, but the deposits proved to be of insufficient quality and quantity to justify development. The shifts in technology from coal to oil for ships led to the designation by the Navy of the Petroleum Reserve N°4 in the Point Barrow area in 1923, but development did not begin until 1941. The Navy also maintained unused reserve lands at Biorka, Cold Bay, Cordova, Hawkins Island, Juneau, Kiska, Portage Bay, Port Graham, Wide Bay, and Yakutat.

The economic boom set off by wartime demand hurt Alaska as many people moved out of state seeking higher-paying employment. While war-related prosperity failed to reach Alaska, the Territory’s economy was hampered by increased costs and lowered availability of labor, supplies and equipment due to surging demand elsewhere. While certain large operations, notably copper and coal mining and fish canning, experienced major growth, the effect was highly localized and many small firms were forced out of business. Despite the economic benefits from gains in natural resource exploitation and the stimulation offered by the construction of the railroad and the development of some 535 miles of vehicular roads, world market price slumps in the years after the Great War led even more people to leave the Territory in search of jobs.

This exodus was reflected in the military presence as well. The Army closed Fort Davis in 1921 and abandoned Fort Egbert, Fort St Michael, Fort Gibbon, and Fort Liscum in 1925, leaving Fort Seward as the only active military facility in the Territory until 1940. In 1927, there were a total of only 255 Army personnel in Alaska. In 1929, Congress appropriated funds to remove military cemeteries from Alaska, indicating a lack of interest in any long-term presence there. The Navy began to retrench as well; it had expanded its communications presence during World War I by building the Cordova radio stations at Hanscom and Eyak and the one at Seward as well as confiscating the stations of the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America at Juneau and Ketchikan. The Juneau and Ketchikan stations were transferred to the Army in 1924, followed by the Seward station in 1927. The Cordova area stations were closed in 1930 and 1933, and the Kodiak and Sitka stations in 1931.

The Navy took possession of the Seward station again in 1932, but it burned in 1935 and was not reestablished until World War II. The St Paul station was turned over to the Bureau of Fisheries in 1937. The only new construction by the Navy consisted of the Cape Hinchinbrook and Soapstone Point direction finding/radio compass navigation stations in the Gulf of Alaska, operated from 1921 through 1937 and 1938, respectively.

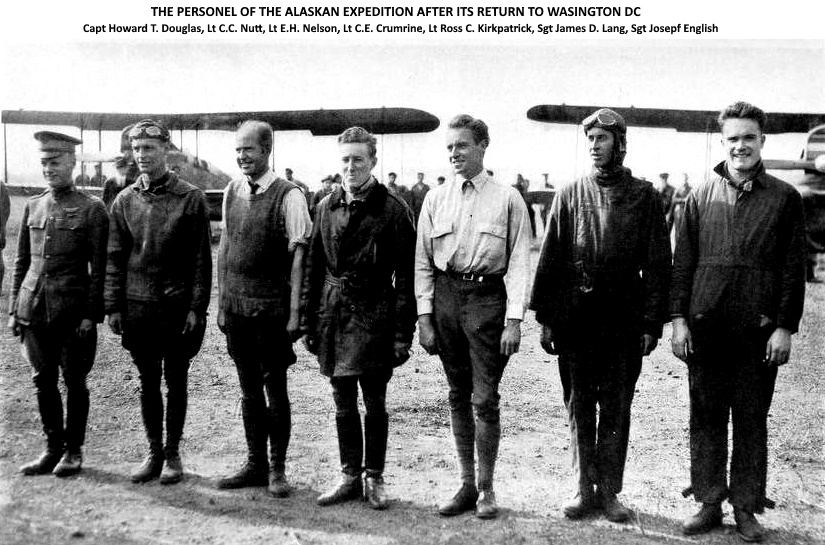

In 1940, the Navy radio station at Dutch Harbor was the only active Navy presence in Alaska. One area which was to have a major impact in Alaska was the development of air travel. The first flight in the Territory was in 1913, and the Signal Corps had an air wing authorized beginning in 1914, but development was slow. To promote military aviation after World War I, the Army sponsored a number of flights to Alaska. In 1920, the Black Wolf Squadron of four DeHavilard DH-4 biplanes flew from New York to Nome and back. In 1924, four two-winged Douglas World Cruisers flew from Seattle along the Alaskan coast and across the Aleutians to the Kuriles then across southern Asia in an around-the-world flight; one ran into a mountainside at Port Moller, becoming the first military aircraft to crash in Alaska. In 1929, Capt Ross G. Hoyt flew a solo mission in a modified Curtiss P-1C Hawk biplane fighter, duplicating the round trip route of the Black Wolf Squadron. The flight ended with a non-fatal crash in Canada on the return leg. Another demonstration of note was the 1934 flight of a squadron of ten Martin B-10 bombers led by Lt Col Henry “Hap” Arnold, who would lead the Army Air Corps in World War II, from Washington DC to Fairbanks and back. All of these flights were staged using civilian and/or ad hoc facilities, as there were no military airfields in the Territory. Civilian aviation caught on more rapidly, with the first commercial aviation venture dating to 1922. Airmail contract runs were being flown by 1924, but civil aviation was also hampered by the lack of facilities. Despite these problems, Alaskans took to aviation to such an extent that by 1938, Alaskan planes carried more cargo than all planes in the rest of the USA.

While Alaska struggled along during the 1920s, the 1930s and the Depression paradoxically led to a minor boom in the North. Alaska benefitted from immigration as unemployment rose in the US, and the increase in the price of gold and the impetus this gave to mining generally provided jobs as did federal relief projects. The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) sponsored the Matanuska Colonization Project, which for the first time established a permanent, stable agricultural community in Alaska. The Public Works Administration (PWA) constructed harbor facilities, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) improved infrastructure in national forests, the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) built other structures and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) ran various cultural projects. The negative aspects of the New Deal in Alaska involved an actual cutting back of road building and maintenance programs, while aviation-related projects never got off the ground even though authorized by the Air Commerce Act of 1926.

Against the backdrop of the Depression, non-voting Territorial Delegate, Anthony J. Dimond, supported legislation in 1934 to construct airfields in Alaska. This attempt coincided with the report of the Drum Board (under Deputy Chief of Staff Maj Gen Hugh A. Drum), which recommended air bases for Alaska and the report of the Baker Board (headed by former Secretary of War Newton D. Baker) which specifically called for cold weather testing, both in 1934. In 1935, the Wilcox National Air Defense Act was passed; it called for the construction of air bases but lacked a provision for funding. Given scarce resources, the Depression, competing for military needs, and the fact that Alaska could muster very little political clout, no funding was found for Alaskan projects. It was not until 1937 that a site for a facility was selected at Fairbanks and funding and construction was delayed even longer.

Renewed isolationism following World War I led to a slashing of military budgets and a decline in facilities, equipment, and manpower. The closings of bases in Alaska were symptomatic of the deeper problems nationwide in a military establishment where promotion was slow and the atmosphere clubby and stagnant. In 1941, the four top field commanders of the Army, including Gen John L. DeWitt who was responsible for Alaska, were veterans of the Spanish-American War. Prerogatives were jealously guarded, and intra-service and inter-service rivalries were often the most serious concerns of the leadership.

The Navy, under the influence of nineteenth century theoretician Adm Alfred Thayer Mahan, was dedicated to large battleships, to the exclusion of other weapons. Neither service took air power seriously from the 1910s into the 1930s, although proselytizing by Billy Mitchell of the Army and RAdm William A. Moffett of the Navy finally resulted in reluctant support of military aviation. Traditional military thinking within the Army stated that the Navy existed to protect the Army while en route to engage the enemy in continental land wars, while that within the Navy held that the Army existed to defend Navy shore installations with capital ships providing the first line of defense and the real projection of power.

The Navy, under the influence of nineteenth century theoretician Adm Alfred Thayer Mahan, was dedicated to large battleships, to the exclusion of other weapons. Neither service took air power seriously from the 1910s into the 1930s, although proselytizing by Billy Mitchell of the Army and RAdm William A. Moffett of the Navy finally resulted in reluctant support of military aviation. Traditional military thinking within the Army stated that the Navy existed to protect the Army while en route to engage the enemy in continental land wars, while that within the Navy held that the Army existed to defend Navy shore installations with capital ships providing the first line of defense and the real projection of power.

The Joint Army/Navy Planning Board, charged with developing a plan for a possible war in the Pacific, was established in 1903. The Joint Board’s first rudimentary plan was completed in 1907. Further planning led to the first War Plan Orange (plans were devised for a single nation-state enemy and color-coded) in 1924. This plan for war with Japan called for the Army to hold the Philippines while the Navy steamed from the West Coast of the US to engage the Japanese fleet in a decisive battle. Numerous revisions of War Plan Orange followed with the concept of a defensive triangle with Hawaii at the center and Alaska and Panama at the extremes forming a defensive perimeter being introduced in 1935.

Alaska’s strategic flank position developed during the period leading up to World War II. However, the Washington Naval Armaments Limitation Treaty (or Five-Power Treaty) of 1922, in addition to limiting the naval tonnage of the US, Britain, and Japan, prohibited the US from fortifying bases in the Aleutians. Between the provisions of the treaty and budgetary constraints, Alaska was not fortified. By 1938, the military had invested around $225 million in facilities in Hawaii but only $1.5 million for work in Alaska, most of that for civilian relief projects. As Conn drily put it, Army planners found it hard to shake their long-held conviction that Alaska was not a critical area.

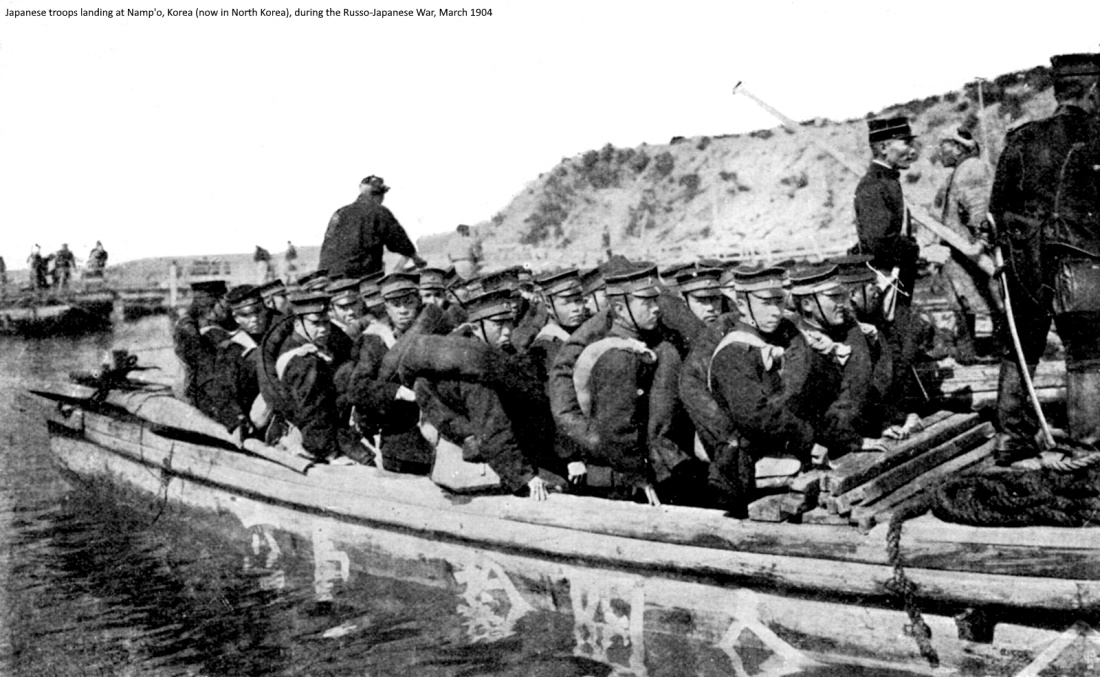

Japan had developed a war plan for a conflict with the US as early as 1907 when tensions over US treatment of Japanese immigrants and the feeling that US mediation had deprived Japan of victories won on the battlefield in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) led to consideration of the US as a potential enemy. The Japanese plan was remarkably like that of the 1907 War Plan Orange. It involved luring the US fleet out to do battle in the area of the Philippines, relying on superior Japanese maneuver, ability, strategy, and psychological toughness to carry the day. However, the US was a minor consideration of the Japanese, who saw China and Russia as the main threats. In fact, the Japanese military establishment was primarily focused on cold weather warfare, ill-prepared for a tropical war and woefully ignorant of the potential US enemy, though Japanese forces rapidly developed expertise in tropical warfare.

Suffering the dislocations of rapid modernization and population growth, Japan was hard hit by the worldwide economic collapse in the early 1930s. Following what was seen as a surrender of national sovereignty at the London Naval Conference in 1930, which led to more limitations on naval construction, hardliners gained greater ascendency in the factionalized government and maneuvered Japan into an invasion of Manchuria as a means of expanding out of the Depression. In 1934, Japan unilaterally withdrew from the 1922 Five-Power Treaty two years before it was scheduled to expire. By 1936, the military had acquired veto power over civilian ministry-level policy decisions and issued a paper entitled Fundamental Principles of National Policy, calling for expansion into Asia and the Pacific, which would bring Japan into conflict with the USSR, China, Britain and ultimately the US.

In 1937, Japan invaded China. Britain’s Far Eastern colonial interests led her to protest, and the US supported the British position. The feeling is often expressed that the US in general, and the Navy in particular, ignored the Japanese threat even after the abrogation of the Five-Power Treaty. This is mainly due to the fact that the once-proposed base at Kiska was not revived. Given the political situation and budgetary realities, it is difficult to see how it could have been at the time. Actually, the Navy had an awareness of the potential problem posed by the need to defend the Northern Pacific.

Beginning in 1922, it had begun studies on basing, with recon in the Gulf of Alaska area being undertaken from 1933 to 1937 and Kodiak established as the site for a base in 1938.