THE SAD DAY

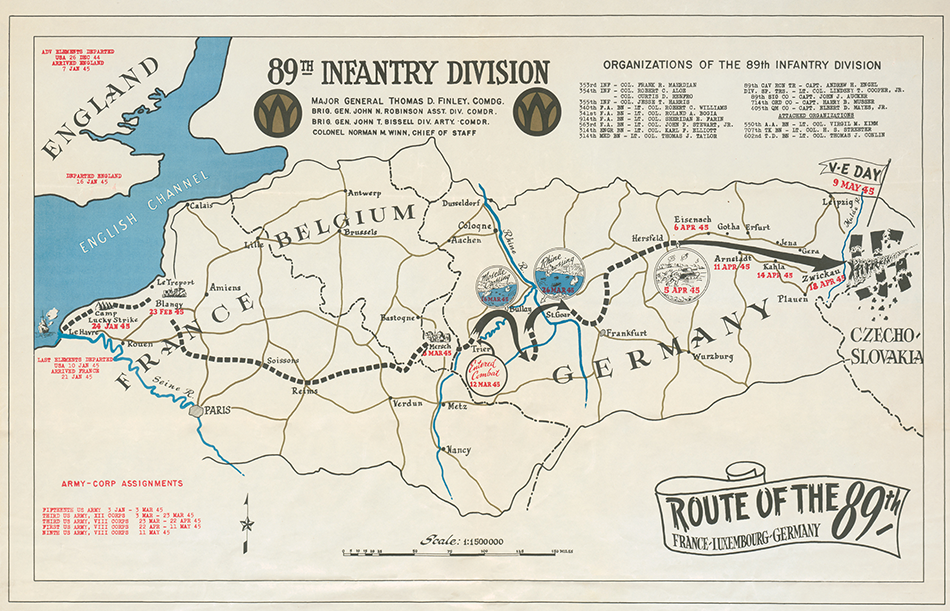

THE 89th LIGHT DIVISION

Again, a train ride through the lovely country but it was back to Camp Roberts for me. We detrained, had our short-arm inspection, and were placed in empty barracks until all those arriving for the 89th Division could be collected and trucked up to the Hunter-Liggett Military Reservation in the nearby rugged coastal mountains near Salinas which, among other things, was known as the location of Randolph Hearst’s fabulous mansion hideout. We grumbled when we saw army barracks again but we didn’t realize that in just a few days we would be wishing we had them.

Again, a train ride through the lovely country but it was back to Camp Roberts for me. We detrained, had our short-arm inspection, and were placed in empty barracks until all those arriving for the 89th Division could be collected and trucked up to the Hunter-Liggett Military Reservation in the nearby rugged coastal mountains near Salinas which, among other things, was known as the location of Randolph Hearst’s fabulous mansion hideout. We grumbled when we saw army barracks again but we didn’t realize that in just a few days we would be wishing we had them.

The 89th Division was still on maneuvers with another light division, the 71st Division, up in these rugged mountains. Let me explain what a light division was supposed to be. A regular, triangular, heavy infantry division is composed of approximately 15.000 men including three infantry regiments, an artillery brigade, and assorted combat and service units such as engineers, medics, etc. About a year before, the Army undertook an experiment with light divisions. Foremost, they would be reduced in size to 9000 men (that’s when a lot of 89ers had previously been transferred out to other divisions preparing for overseas movement) and would use much lighter weaponry and equipment, e.g., jeeps or mules as the prime movers for pack artillery and equipment. The 89th used jeeps and the 71st used mules as prime movers for weapons and supplies, augmented by human power in both cases, and the maneuver was to test the efficacy of one versus the other. In the end, it was concluded that light divisions, in general, were feasible only in very special and limited conditions. The10th Mountain Division was the only light division in the experiment to be retained and was soon sent to Italy. This meant that approximately 6000 soldiers would have to be transferred into each of the two reorganized heavy divisions to bring them up to strength. These transfers into the 89th, including we ASTPers from OCS, began at Camp Roberts and Hunter-Liggett and continued when we arrived at Camp Butner as described below.

We did not realize it at the time, but this new and sometime jolting new assignment for most of us former ASTPers and Air Cadets was really a break of immeasurable proportions because it delayed our departure for combat by six months while we were expanded, re-equipped and trained. Most other ASTPers and Air Cadets were sent as replacements directly to infantry divisions ready to be deployed. One of my brothers-in-law had this experience and was wounded twice in France and Germany.

We did not realize it at the time, but this new and sometime jolting new assignment for most of us former ASTPers and Air Cadets was really a break of immeasurable proportions because it delayed our departure for combat by six months while we were expanded, re-equipped and trained. Most other ASTPers and Air Cadets were sent as replacements directly to infantry divisions ready to be deployed. One of my brothers-in-law had this experience and was wounded twice in France and Germany.

My best friend in college and long after was sent to the 106th Infantry Division and became a machine gunner. This was the green division spread thinly on the 100-mile front directly facing where the Germans broke through at the beginning of the Battle of the Bulge. He was wounded, captured, and remained in a prison camp until the end of the war and suffered from trench foot for the rest of his life. In retrospect, while we had our losses, it was a lucky break for most of us who survived the war.

Within a couple of days, we were assembled, loaded on 2X4 trucks, and began the trek up to the mountains. I can remember the scene vividly. In a large, reasonably flat field, 2×4 trucks were arranged in a large circle with their fronts facing outward. On the tailgate of each truck, arranged in a large circle, were one or more officers and non-coms representing each Infantry Regiment, Artillery Battalion, and other major units. We were all dumped in the middle of the field and then, in order, each officer read out the names and serial numbers of the soldiers assigned to his unit(s), and those selected were assembled and trucked to where the units were bivouacked.

Each time the ‘Ks’ was reached by an infantry officer, I would hold my breath in hopes that I didn’t hear my name. The opposite was true when artillery selections were made. Gradually, the number of us waiting for the call was diminished. Finally, they were done but there still were a fairly large number of us left. Somehow or other, I missed (or they missed) my name and on rechecking the list, it was ascertained that I had been assigned to the 340th Field Artillery Battalion. As a form tank destroyer gunner, this made sense, and I was much relieved.

Each time the ‘Ks’ was reached by an infantry officer, I would hold my breath in hopes that I didn’t hear my name. The opposite was true when artillery selections were made. Gradually, the number of us waiting for the call was diminished. Finally, they were done but there still were a fairly large number of us left. Somehow or other, I missed (or they missed) my name and on rechecking the list, it was ascertained that I had been assigned to the 340th Field Artillery Battalion. As a form tank destroyer gunner, this made sense, and I was much relieved.

Off we went to the 340th bivouac area further up the mountains where I was assigned to Battery B. Old-timers were housed in pyramidal tents, which held approximately 6 to 12 soldiers, but there were none left for the new arrivals. We were issued pup tents (two shelter halves are combined to make a low, two-man tent) with some straw for bedding. Army life was changing back to normal about as fast and as brutal as possible.

As the exercises with the 71st continued, probably just to keep us all busy before we could be shipped out, we got a little taste of what warfare in the mountains could be like, such as that experienced by our troops in Southern Italy. It was tough but as I recall there was no more than the usual bitching and, we took the fortunes of war in good stride and buckled down to prepare ourselves for what lay ahead. In an interview that the Battery CO, Capt Lightbaum had with each new arrival, I expressed my desire to be a gunner again which seemed to meet with his approval. Soon, I was backing up one of the gunners and was happy with the prospect of being assigned as a gunner when the battery was eventually expanded and equipped with 105-MM guns.

I had one amusing diversion. Some loony brass in the Battalion or Brigade thought it would be nice to have a ‘pass in review’ parade, maybe to see who would be the first to break a leg on the uneven and potholed field. My Battery Commander, Captain Lightbaum (a fearsome man), also wanted a bugler to play taps at night and I volunteered (it was easy duty) having messed around a bit with a bugle when I was in camp as a youngster. I was terrible and not improving. Whoever thought the parade was a great idea also thought they should have a band playing. Of course, there was no band so they assembled the available buglers. Because I was so bad, I was made the band marching leader and didn’t have to play. Ah, the triumphs of life.

CAMP BUTNER – NORTH CAROLINA – 89th Infantry Division

The day finally arrived when we packed up our tents, was trucked back down to Camp Roberts, and were soon loaded on troops trains (after a short arm check, of course) for the long trip to North Carolina. We went down the coastline and then across the Mohave desert, stopping at the familiar Needles for exercise outside the train cars, all the way to New Orleans, and then up the east coast right into Camp Butner located between Hendersonville and Raleigh North Carolina. Something happened of interest on that trip that later on had significant ramifications for me. When at B Btry in Hunter Liggett I became friends with an ex-ASTPer who we called ‘Red’ for obvious reasons but, unfortunately, I can’t remember his name at all.

He was a very cultured gentleman whom I respected immensely. Again, we passed through the breathtaking and interesting country giving me an even larger perspective of the makeup of our large and beautiful nation. In a long and continuous letter to my mother, I was inspired to describe in great detail what I saw and how and why it impressed me. At one point Red asked what I was doing and I let him read it. He told me he was impressed with my writing capability and should think about becoming a writer, a journalist, or something of that nature. Because of my respect for his education and maturity, this impressed and stayed with me, as we shall see if you stay with my story.

He was a very cultured gentleman whom I respected immensely. Again, we passed through the breathtaking and interesting country giving me an even larger perspective of the makeup of our large and beautiful nation. In a long and continuous letter to my mother, I was inspired to describe in great detail what I saw and how and why it impressed me. At one point Red asked what I was doing and I let him read it. He told me he was impressed with my writing capability and should think about becoming a writer, a journalist, or something of that nature. Because of my respect for his education and maturity, this impressed and stayed with me, as we shall see if you stay with my story.

Butner was a huge, sprawling army base typical of the times with rows upon row of barracks, mess halls, and offices supplemented by a hospital, space for artillery and vehicles, movie houses, USO, recreation hall, chapels, and what have you. It was relatively flat with plenty of space for maneuvers and firing exercises. It was located fairly close to Raleigh and Durham, which proved to be good ‘liberty’ towns and we quickly learned to covet those lovely southern belles.

Shortly after we settled in I got my first jolt. While there were three artillery battalions in a light division, which would be converted and expanded to handle the new 105-MM guns being supplied, a brand new battalion needed to be created to handle the medium 155-MM artillery guns that were standard with a heavy infantry division.

Transfers from existing artillery battalions and new replacements arriving in Camp Butner formed this battalion, the 563rd Field Artillery Battalion. I was one of those ‘selected out’ of the 340th and assigned to the Service Battery of the 563rd. I was not happy. I didn’t want to leave my newfound buddies in Battery B and I certainly didn’t want to be in a service battery, which handles rations, ammunition, and supplies. But, as usual, no one asked me or gave a dam what I wanted. I haven’t got a clue as to why I was picked for the 563rd and assigned to its Service Battery and would rather not dwell on it.

Transfers from existing artillery battalions and new replacements arriving in Camp Butner formed this battalion, the 563rd Field Artillery Battalion. I was one of those ‘selected out’ of the 340th and assigned to the Service Battery of the 563rd. I was not happy. I didn’t want to leave my newfound buddies in Battery B and I certainly didn’t want to be in a service battery, which handles rations, ammunition, and supplies. But, as usual, no one asked me or gave a dam what I wanted. I haven’t got a clue as to why I was picked for the 563rd and assigned to its Service Battery and would rather not dwell on it.

Then we all settled down and began our training. I was assigned as a clerk (again my MOS seemed to haunt me) in the section responsible for food rations, gasoline, and miscellaneous supplies for the battalion. The section was assigned one 2×6 truck for the pickup and delivery of food and supplies throughout the battalion. A Warrant Officer assisted by a three-rocker sergeant commanded it, a total of six or seven men. Another guy (I can’t remember his name exactly but I  believe his last name was Wilkie) and I were assigned to pick up the daily food rations each day, divide them up for each battery according to their roster size for the day, and delivering them. The assigned truck driver with T/5 rank was a Pacific combat veteran and it was obvious his stay with us would be temporary.

believe his last name was Wilkie) and I were assigned to pick up the daily food rations each day, divide them up for each battery according to their roster size for the day, and delivering them. The assigned truck driver with T/5 rank was a Pacific combat veteran and it was obvious his stay with us would be temporary.

Loving to drive and looking for some rank, I became his understudy helping to maintain and clean the truck with occasional driving assignments, mostly to the depot. Dividing the rations was the biggest challenge. How do you divide one cow carcass into five Batteries, some larger than others? Even after working out the math, how did you carve it up into pieces a mess sergeant could use or would seem fair to him? The seriousness of this problem was compounded because neither of us know a damn thing about butchering. With the help of disgusted mess sergeants and cooks, and trial and error techniques, we finally worked it out somehow.

THE CREW

One day, while I was unloading some 105-MM shells from our truck, the tailgate chain gave way, and down I fell with several shells right behind me, both hitting the ground at the same time. First I was taken to the Battalion aid station and then to the base hospital where I remained for several days for observation. I had nothing more than a bruised back, or so it seemed at the time, but shortly after I was discharged in 1946 and before heading off for college, I was digging up the weeds in a neighbor’s yard when my back suddenly gave away and I fell to the ground in severe pain due to a degenerated disc. This was to be my wartime disability, for sure, and it’s only gotten worse as time goes by. I never bothered to submit a claim and wouldn’t let a VA hospital near my back.

Sometime shortly after we arrived in Butner, I was given my first and only furlough and had a week at home. I can’t remember many particulars but have some pictures of myself with all the family. Of course, none of my buddies were at home and I had no girlfriend so it was pretty routine, especially since I had seen so much of Mom in Oregon. Nevertheless, It was sure nice to be home again and the center of attention. Went to NYC and saw the musical ‘Oklahoma’ on a free ticket and also blew my wad on taking an old family friend, Maurine, out to a swanky Park Ave café. I was the only non-officer in the place. Then, back to reality.

Old booming Capt Lightbaum was also transferred to the 563rd, with a promotion to major, and our paths crossed once again. We were on a field firing exercise simulating an action problem and I was driving our truck full of shells and rations to an appointed spot. It was hilly and the truck was heavily loaded so I shifted into four-wheel drive, which is quite noisy. Unbeknownst to me, Lightbaum was in the middle of communicating firing instructions to the various Batterys, or vice versa,  and the noise of my truck was making it difficult for him to hear or be heard. At any rate, after much flagging down and shouting, his booming voice came finally through… ‘Shut down that goddamn truck’. I have a feeling that that incident was a contributing factor to my remaining a Private until, and only by an Act of Congress; I was promoted to Private First Class while in combat. I also can’t help but wonder how, during actual combat firing, Major Lightbaum was able to maintain command if the comparatively slight noise I had been causing so throw him out of control. I’ll never know and he’s not around to tell me.

and the noise of my truck was making it difficult for him to hear or be heard. At any rate, after much flagging down and shouting, his booming voice came finally through… ‘Shut down that goddamn truck’. I have a feeling that that incident was a contributing factor to my remaining a Private until, and only by an Act of Congress; I was promoted to Private First Class while in combat. I also can’t help but wonder how, during actual combat firing, Major Lightbaum was able to maintain command if the comparatively slight noise I had been causing so throw him out of control. I’ll never know and he’s not around to tell me.

Otherwise, life at Butner wasn’t too bad. North Carolina has many virtues and amongst its highest are the beautiful women with lovely accents who live there. Many who worked in Raleigh, Durham, and Henderson, came to dances on base or at USOs in town. Also met lovely girls at Duke and Randolph Macon; what a change from what an enlisted man usually runs into.

DUKE UNIVERSITY

Also dated several others but the last was the best or worst, depending on how you look at it. Edna and I fell in love or thought we did, but she did have a boyfriend from high school who was still in the picture. I would come in whenever I could get a pass and had the bus fare. She was undemanding and sweet and loved to neck. In fact, one night as our  departure approached, we decided to get the bus to South Carolina and get married immediately. There was a long line at the bus station, a common event in those days, and after about three hours of waiting, we called it quits. Later events proved how lucky I was.

departure approached, we decided to get the bus to South Carolina and get married immediately. There was a long line at the bus station, a common event in those days, and after about three hours of waiting, we called it quits. Later events proved how lucky I was.

CHRISTMAS AT HOME

The day of departure grew closer and closer and preparations were being made for packing and shipping all our guns (except personal arms), vehicles, equipment; everything conceivable. It was also the time for the last weekend passes and I wanted desperately to get home for Christmas. The hitch was that the passes were limited to two days and within a radius of 250 miles, as we had been officially alerted for overseas movement. The second hitch was transportation. When I arrived at the Henderson RR station, there were hundreds of us waiting to get on the next train which, when it finally arrived late from the south, was already teeming with GIs and it was impossible to get on. Next, we hit the highway to hitchhike but every car that passed was already filled to the brim. Somehow, we got a lift to St Petersburg and then took a bus to Richmond and I was feeling a little better but that didn’t last long. Someone gave us a lift from the bus station to just north of town where Route One continued to DC. There were hundreds, maybe thousands (or at least it seemed so) of GIs, Sailors, and Marines trying to get a lift. To add to our anxiety, it began to snow. Finally, a big, open trailer truck stopped. It barely had a floor and only ropes for guide rails. The driver said it would be rough but he would take all who wished to pile on and a bunch of us were on our way. Others, I think, thought we were committing suicide.