To add to our misery, and probably one of the dumbest ideas to emerge on how to keep us busy, some bright officer bucking for a Bronze Star got the idea that we should build trench ditches around each tent to provide protection against air raids. Even when our boys hit the beach six months before, the Luftwaffe was barely seen, and wasting their dwindling resources on us would have been preposterous. That would have been bad enough but what happened next took the cake. There was an unseasonably early thaw. The company and battery streets at Lucky Strike became an unbelievable quagmire of mud reminiscent of scenes from World War I. We had earlier been issued ‘combat boots’, an example of how badly designed some of our equipment was. There were buckles above the ankle with a rubber sole and moisture-absorbing leather. In the snow, to which we were soon again to be immersed in Germany, they proved that they were almost useless and a leading cause of trench feet. GI goulashes were not much better. The streets were laborious to walk on and avoided when possible. An incident can clearly demonstrate the discomfort of mud, mud, and mud.

To add to our misery, and probably one of the dumbest ideas to emerge on how to keep us busy, some bright officer bucking for a Bronze Star got the idea that we should build trench ditches around each tent to provide protection against air raids. Even when our boys hit the beach six months before, the Luftwaffe was barely seen, and wasting their dwindling resources on us would have been preposterous. That would have been bad enough but what happened next took the cake. There was an unseasonably early thaw. The company and battery streets at Lucky Strike became an unbelievable quagmire of mud reminiscent of scenes from World War I. We had earlier been issued ‘combat boots’, an example of how badly designed some of our equipment was. There were buckles above the ankle with a rubber sole and moisture-absorbing leather. In the snow, to which we were soon again to be immersed in Germany, they proved that they were almost useless and a leading cause of trench feet. GI goulashes were not much better. The streets were laborious to walk on and avoided when possible. An incident can clearly demonstrate the discomfort of mud, mud, and mud.

The insides of our tents were relatively dry, i.e., very damp with the wetness penetrating our thin sleeping bags, another Quartermaster supply debacle, and the straw underneath. About 50 yards from our tent was the Battery latrine, just in front of a marked landmine area. Like many others of my comrades, I was suffering from diarrhea and one night it hit me with a vengeance. I unentangled myself from my bedroll as quickly as possible, jumped into my  boots, and, in my long johns, started rushing towards the latrine. Three or four steps out of the tent, my right boot got stuck firmly in the mud but I was forced to rush on without it, slowed only when the same thing happened to my left boot a few steps later. By the time I reached the latrine, irreparable damage had been done. An hour later, I struggled back to my tent, pulled my only other pair of LJs out of my duffel bag, and tried to get back to sleep.

boots, and, in my long johns, started rushing towards the latrine. Three or four steps out of the tent, my right boot got stuck firmly in the mud but I was forced to rush on without it, slowed only when the same thing happened to my left boot a few steps later. By the time I reached the latrine, irreparable damage had been done. An hour later, I struggled back to my tent, pulled my only other pair of LJs out of my duffel bag, and tried to get back to sleep.

To complete the agony of this story, it took me all the next day boiling the soiled LJs over and over again in a tin bucket over an open fire until I could manage to wear them again (they stood by themselves) but I got rid of them as soon as I could.

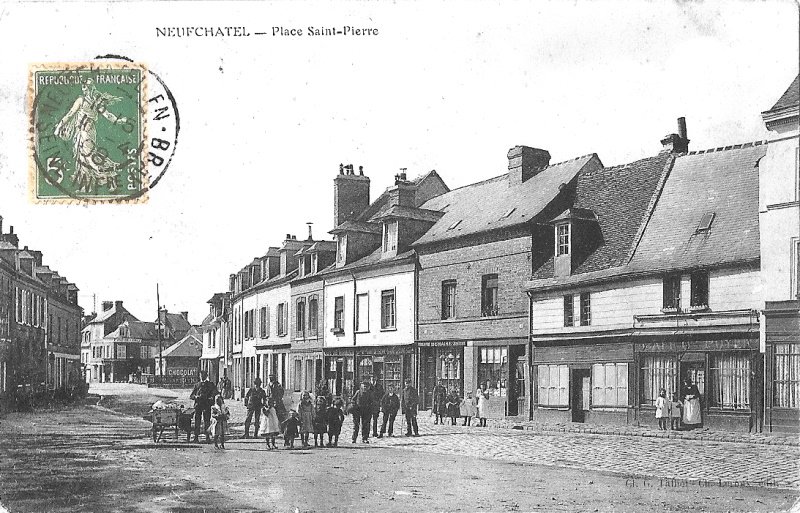

It seemed like ages but finally, we all left Lucky Strike and headed out to our individual unit locations, ours being on the outskirts of Neufchatel-en-Bray. My buddies and I ended up in a cow barn, not fancy but dry and comparatively comfortable. The biggest joy to us all was that we again had our own mess. Naturally, I was the first soldier ‘selected’ for KP (Kitchen Police) but this time it was welcomed. I remember that day clearly. We had pancakes and I gobbled them down so quickly, our mess sergeant told me to eat all I want. He was one of the five mess sergeants we distributed rations to daily, so they were usually pretty nice to my partner, Wilkie, and me. I believe I ate 20 flapjacks. Funny, when I got back to civilian life my passion for pancakes was considerably reduced but over the years it has returned.

Neufchatel-en-Bray was a small town in fairly good shape but there wasn’t much to buy or do but walk about a bit. One night, with some of my Service Battery buddies and a (very) few French occupation francs in my pocket, we took the stroll and ended up (surprise) in our first French bar, a very typical one I’m sure. We all ordered a ‘Calvados’; a very famous apple brandy produced in Normandy, which except for some weak beer was probably all they had.

Neufchatel-en-Bray was a small town in fairly good shape but there wasn’t much to buy or do but walk about a bit. One night, with some of my Service Battery buddies and a (very) few French occupation francs in my pocket, we took the stroll and ended up (surprise) in our first French bar, a very typical one I’m sure. We all ordered a ‘Calvados’; a very famous apple brandy produced in Normandy, which except for some weak beer was probably all they had.

Bear in mind that I was no drinker, I didn’t even like beer, and when I took my first taste at this bar it almost blew off my head. ‘Till this day, I always claim it gave me an ingrown toenail. The stuff must have been made within the past three to six months and it was raw!

In 1983, during the summer before we returned to the States from eight years in Vienna with the United Nations, my wife, son and I took a long-planned two-week gastronomic tour through France by car. I had spent a year planning it. We drove through Neufchatel-en-Bray but I couldn’t recognize it. It now is a small city.

In 1999, during the 89th ‘Tour of Remembrance’ through Europe, my son and I visited a very similar bar in a very similar small town nearby, and drank some Calvados together. We all had aged very well.

My Battalion, the 563rd Field Artillery (medium, 155-MM guns) was assembled with all its equipment and we were ready to roll. The ‘Front’ is a term more attached to World War I but that’s what we were soon off to, wherever it was. The ‘Battle of the Bulge’ was winding down and the Division received orders to move into the area around Mersch, Luxembourg, in preparation for going into the line, and assigned to the XII Corps of General Patton’s Third Army.

My Battalion, the 563rd Field Artillery (medium, 155-MM guns) was assembled with all its equipment and we were ready to roll. The ‘Front’ is a term more attached to World War I but that’s what we were soon off to, wherever it was. The ‘Battle of the Bulge’ was winding down and the Division received orders to move into the area around Mersch, Luxembourg, in preparation for going into the line, and assigned to the XII Corps of General Patton’s Third Army.

On March 3, infantry and artillery battalions loaded into ancient ’40-and-8′ freight cars for the long, tedious journey across France. Other units, like ours, moved out into convoy. The trip averaged over three hundred miles with blown bridges, ruined roads, and detours causing frequent delays. There was much to see if you were driving or sitting in the front seat of a truck, particularly when we went through Reims and similar places. Even if you were fortunate enough to be sifting on the bench at the very rear of the truck, your view was very limited. But being the assistant or backup driver, I did get to sit in the front seat. Of course, my turn was in the middle of the night in a complete blackout and all I got out of it was a neck ache and sore eyes. The head of our little supply group was a Warrant Officer not often seen back in the States – he was busy trying to make like an officer and was lazy to boot. It was cold out and the river’s cabin was buttoned up. The gastronomic turmoil my stomach had been through beginning with the seasickness and ending with the pancakes could no longer be contained. I let (I really had no control) some depth charges go and was at first horrified but then happy to see Epstein cringe with disgust.

Sweet revenge but it ruined any future chances or promotion, which by now were almost non-existent anyway. In fact, it took an Act of Congress to get me promoted to Pfc. We assembled in a small village north of the Luxembourg Capital and near Echternach, ready for our first combat mission. It was here that I had my first chance to try out my high school German with the friendly Luxembourgers. In 1939, when in high school, I concluded we would soon be in a war with Germany and took German classes for two years. As it turned out, it didn’t help me with the war effort but after the war, with all those pretty and lonely Fräuleins, well that’s another story.

Sweet revenge but it ruined any future chances or promotion, which by now were almost non-existent anyway. In fact, it took an Act of Congress to get me promoted to Pfc. We assembled in a small village north of the Luxembourg Capital and near Echternach, ready for our first combat mission. It was here that I had my first chance to try out my high school German with the friendly Luxembourgers. In 1939, when in high school, I concluded we would soon be in a war with Germany and took German classes for two years. As it turned out, it didn’t help me with the war effort but after the war, with all those pretty and lonely Fräuleins, well that’s another story.

FIRST MISSION – MOSELLE CROSSING

Our first battleground was in the forested Eifel highland as the 89th was committed on March 12. As we were the Service Battery for an artillery battalion, we were not usually in the forefront of things. Normally, we brought up food and shells for our 563rd Batteries. When there was a major obstacle to overcome and massing of infantry was necessary, such as in major river crossings, our trucks would be pressed into service to move the troops and ammunition to the riverbanks.

Our first call soon came to provide transportation to the infantry for the assault I across the Moselle at three points. We approached the assigned sectors under heavy fog on the morning of March 15, watching our ‘passengers’ jump down off our truck, assemble, and take their positions before climbing into boats and silently paddling across the river. In my heart was admiration for their courage and probably some relief that I was not amongst them. By the 16th, the Engineers had completed the Moselle span between Alf and Bullay, and troops, armor, and artillery poured across. I vividly remember walking down the heavily shelled front street and looking into the ground floor of a battered storefront where a dead GI lay, his head laid wide opened by a bullet or shell. By this time, I had seen many dead Germans but this was the first American and it really shook me. That could be me. Instantly, the war changed from being something removed to something very real and close. It was the beginning of a rough but rapid maturity for this soldier.

I don’t remember much detail of what happened in these days as the Germans were scrambling to get back to the Rhine for the next, and last it turned out, an organized attempt at defense. On March 20 the 89th took its largest bag of prisoners to date, capturing 354, and entered Worms on the Rhine the following day.

I don’t remember much detail of what happened in these days as the Germans were scrambling to get back to the Rhine for the next, and last it turned out, an organized attempt at defense. On March 20 the 89th took its largest bag of prisoners to date, capturing 354, and entered Worms on the Rhine the following day.

March 1945 Supporting the Armor of the 89th Infantry Division. On the West Bank of the Rhine River outside the town of Kaub, Germany

The Rhine Crossing (Our Biggest Battle)

March 24 marked the beginning of the Division’s second and most impressive combat phase. The excitement, intensity, movement, and anxiety increased, at least for me. New units were attached to the Division for the crossing such as mobile anti-craft guns, heavy artillery, combat engineers, etc. Equipment was arriving, such as pontoons and treadways and even the US Navy showed up with assault boats. We were part of a major campaign involving the last major impediment to capturing the heartland of Germany. Service Battery of the 563rd Field Artillery Battalion was only a small unit in the impressive logistical support mounted for crossing the mighty Rhine but it gave us great satisfaction to be involved.

For me, as with previous river crossings, it began by transporting infantrymen and their equipment to their embarkation assembly points. In addition to our own four artillery battalions, 15 additional battalions from Corps were supplied, a formidable array of firepower.

Unfortunately, it seems some bright staff or higher command officer decided our attack would be a surprise one, taken at night and without forewarning, meaning no artillery support. It was another case of digging trench ditches at Lucky Strike after the fly was out of the coup. Many 89ers that were wounded or lost buddies crossing the Rhine and climbing the hills on the other side remain bitter to this day over what seemed to them to be a tactical blunder.

Unfortunately, it seems some bright staff or higher command officer decided our attack would be a surprise one, taken at night and without forewarning, meaning no artillery support. It was another case of digging trench ditches at Lucky Strike after the fly was out of the coup. Many 89ers that were wounded or lost buddies crossing the Rhine and climbing the hills on the other side remain bitter to this day over what seemed to them to be a tactical blunder.

We crossed from Oberwesel, just below St. Goar where the main crossing took place. St. Goarshausen was the main objective. It is a muddle of confusion in my memory. Of course, with our artillery and trucks, we had to wait until the Engineers built a pontoon bridge across the Rhine, which wasn’t long coming. As we crossed, I remember how much the houses in the small villages on the Rhine reminded me of scenes from Walt Disney cartoons. By the end of the month, we had cleared the whole area. Our battalion then traveled downriver going through Wiesbaden, which, unlike other cities we had seen, was still largely intact because of its status as a hospital center. We came to a halt in the country outside the city about April 1 and spent the night in a field mostly surrounded by thick woods. Since we were halted for the night, some more enterprising truck drivers removed the thick tarpaulin from their trucks to make a tent-like structure that was lightproof, permitting one to read and write letters.

When going on guard that night, we had been warned to watch out for armed German stragglers seeking to return to their units under cover of the woods and darkness. In the late afternoon, a supply truck stopped at our encampment with an unexpected and pleasant surprise. It seems our Division had liberated a supply of French champagne, which the Germans had previously looted from France, and every man was “issued” a bottle.

Wilkie and I were scheduled to go on guard duty at about 10:00 p.m. After supper, we retired to our truck and each proceeded to drink his bottle in its entirety. Neither of us was seasoned drinkers or use to the strange feelings the ‘bubbly’ liquid could cause. It is no surprise then that when we jumped off our truck’s tailgate to go on guard, we were feeling no pain. With what happened next, I was probably as close or closer to death than any time in combat. There was a first-generation Italian boy from New York in our Battery, a real nice guy, but who fit the stereotype of a Brooklynite, accent, looks and all, to a ‘T’. As such, even I, a Brooklynite myself, often teased him.

Wilkie and I were scheduled to go on guard duty at about 10:00 p.m. After supper, we retired to our truck and each proceeded to drink his bottle in its entirety. Neither of us was seasoned drinkers or use to the strange feelings the ‘bubbly’ liquid could cause. It is no surprise then that when we jumped off our truck’s tailgate to go on guard, we were feeling no pain. With what happened next, I was probably as close or closer to death than any time in combat. There was a first-generation Italian boy from New York in our Battery, a real nice guy, but who fit the stereotype of a Brooklynite, accent, looks and all, to a ‘T’. As such, even I, a Brooklynite myself, often teased him.

Unfortunately, I forget his name. In 1939, when in high school, it seemed very clear to me that the United States would eventually go to war with Nazi Germany so I elected to study German for two years on the sound, it turned out, the theory that I would be there too. My German-speaking capabilities were obviously not great, and it never made any contribution to the war effort, but when your buddies speak none, it gave you significant advantages with certain parties, which I will elucidate a bit later. Anyway, as we patrolled the perimeter I could see candlelight coming from a fold in his tarp. I said to Wilkie ‘Watch me scare the pants off him’ and shouted out in German for him to come out with his hands up. Well, this ‘buddy’ didn’t speak any German but recognized when it was being spoken and his reaction was immediate and completely unexpected, to say the least. Without a moment’s hesitation, he picked up his carbine and fired blindly in the direction of my voice. While I don’t recommend it, it is the fastest sobering-up technique imaginable. He was not a happy man. The next worry was that having certainly awakened the First Sergeant and Corporal of the Guard, we would shortly get chewed out or worse. Strangely, not a single person moved to investigate. After all, those bad Germans were out in them there woods minding their own business. Whatever, I learned a good lesson there.