Source Document: Armor in the Huertgen Forest. The Kall Trail and the Battle of Kommerscheidt by Captain Mike Sullivan. The mission of Armor is to close with and destroy the enemy by means of fire, maneuver, and shock effect. (FM-17-15, Tank Platoon, April 3, 1996)

Today’s armor force is based on a highly flexible, mobile, and lethal armor doctrine. Terms such as maneuver and shock effect are the keynote phrases of the modern US armor community. Steeped in tradition, the US armor forces have long sought to fight a war of maneuver where speed and cunning mimicked the cavalry battles of old. But in late 1944, when US mechanized forces entered the Huertgen Forest, they lost their ability to fight as a maneuver force. On terrain both unfamiliar and unsuitable for maneuver warfare, and denied the elements of speed and maneuver, US armor was no longer a highly flexible arm of the combined arms team. On the Kall Trail in November 1944, both the restrictive terrain of the Huertgen Forest and the stubborn resistance of the German defenders seriously challenged the US armor doctrine. The lessons learned from the Kall Trail battle are highly applicable to today’s armor force as we find our tanks in increasingly restrictive terrain, whether in the streets of Somalia or the rugged hills of the Kosovo.

Today’s armor force is based on a highly flexible, mobile, and lethal armor doctrine. Terms such as maneuver and shock effect are the keynote phrases of the modern US armor community. Steeped in tradition, the US armor forces have long sought to fight a war of maneuver where speed and cunning mimicked the cavalry battles of old. But in late 1944, when US mechanized forces entered the Huertgen Forest, they lost their ability to fight as a maneuver force. On terrain both unfamiliar and unsuitable for maneuver warfare, and denied the elements of speed and maneuver, US armor was no longer a highly flexible arm of the combined arms team. On the Kall Trail in November 1944, both the restrictive terrain of the Huertgen Forest and the stubborn resistance of the German defenders seriously challenged the US armor doctrine. The lessons learned from the Kall Trail battle are highly applicable to today’s armor force as we find our tanks in increasingly restrictive terrain, whether in the streets of Somalia or the rugged hills of the Kosovo.

APPROACH TO HUERTGEN

On July 21, 1944, the New York Herald-Tribune headlines had screamed, Allies in France Bogged Down on Entire Front, but by September, the tide had changed and the Allies were literally at Germany’s doorstep. After the successful breakout from Normandy in Operation Cobra and the defeat of the German counter-attack at Mortain, armor spearheads drove deep into the heart of the German army. Thousands of Allied tanks charged across the open fields of France and into the plains of Belgium. Limited by fuel shortages and Allied air superiority, German armored units were rapidly depleted.

As the Americans approached the city of Aachen, the birthplace of Charlemagne and now the first German city threatened with capture, it seemed clear nothing could stop the weight of the Allied armor onslaught. As the Allies neared Germany, Gen Courtney Hodges’ 1st Army approached Aachen. The 1st Army had moved north of the Ardennes to support Montgomery’s 21st Army Group, on his left.

As the Americans approached the city of Aachen, the birthplace of Charlemagne and now the first German city threatened with capture, it seemed clear nothing could stop the weight of the Allied armor onslaught. As the Allies neared Germany, Gen Courtney Hodges’ 1st Army approached Aachen. The 1st Army had moved north of the Ardennes to support Montgomery’s 21st Army Group, on his left.

Gen Hodges’ three corps reached the German border with enough combat power to attempt a breach into the enemy homeland, but as the battle for Aachen began, Hodges felt it was important to protect his right flank from a potential attack. As a veteran of World War One, Gen Hodges recalled the attack launched from the Argonne Forest against American forces in 1918. With the Huertgen Forest, another massive forest, on his flank, Hodges ordered the units to protect his right.

Gen Hodges’ three corps reached the German border with enough combat power to attempt a breach into the enemy homeland, but as the battle for Aachen began, Hodges felt it was important to protect his right flank from a potential attack. As a veteran of World War One, Gen Hodges recalled the attack launched from the Argonne Forest against American forces in 1918. With the Huertgen Forest, another massive forest, on his flank, Hodges ordered the units to protect his right.

The Germans were surprised. As they noted in an after-action report of the fighting in the Huertgen Forest: The German command could not understand the reason for the strong American attacks in the Huertgen Forest after the effectiveness of the German resistance had been ascertained. There was hardly a danger of a large-scale German operation pushing through the wooded area into the region south of Aachen, as there were no forces available for the purpose and because tanks could not be employed in the territory. In fact, such an operation was never planned by us.

The Germans were surprised. As they noted in an after-action report of the fighting in the Huertgen Forest: The German command could not understand the reason for the strong American attacks in the Huertgen Forest after the effectiveness of the German resistance had been ascertained. There was hardly a danger of a large-scale German operation pushing through the wooded area into the region south of Aachen, as there were no forces available for the purpose and because tanks could not be employed in the territory. In fact, such an operation was never planned by us.

AN UPHILL BATTLE AHEAD

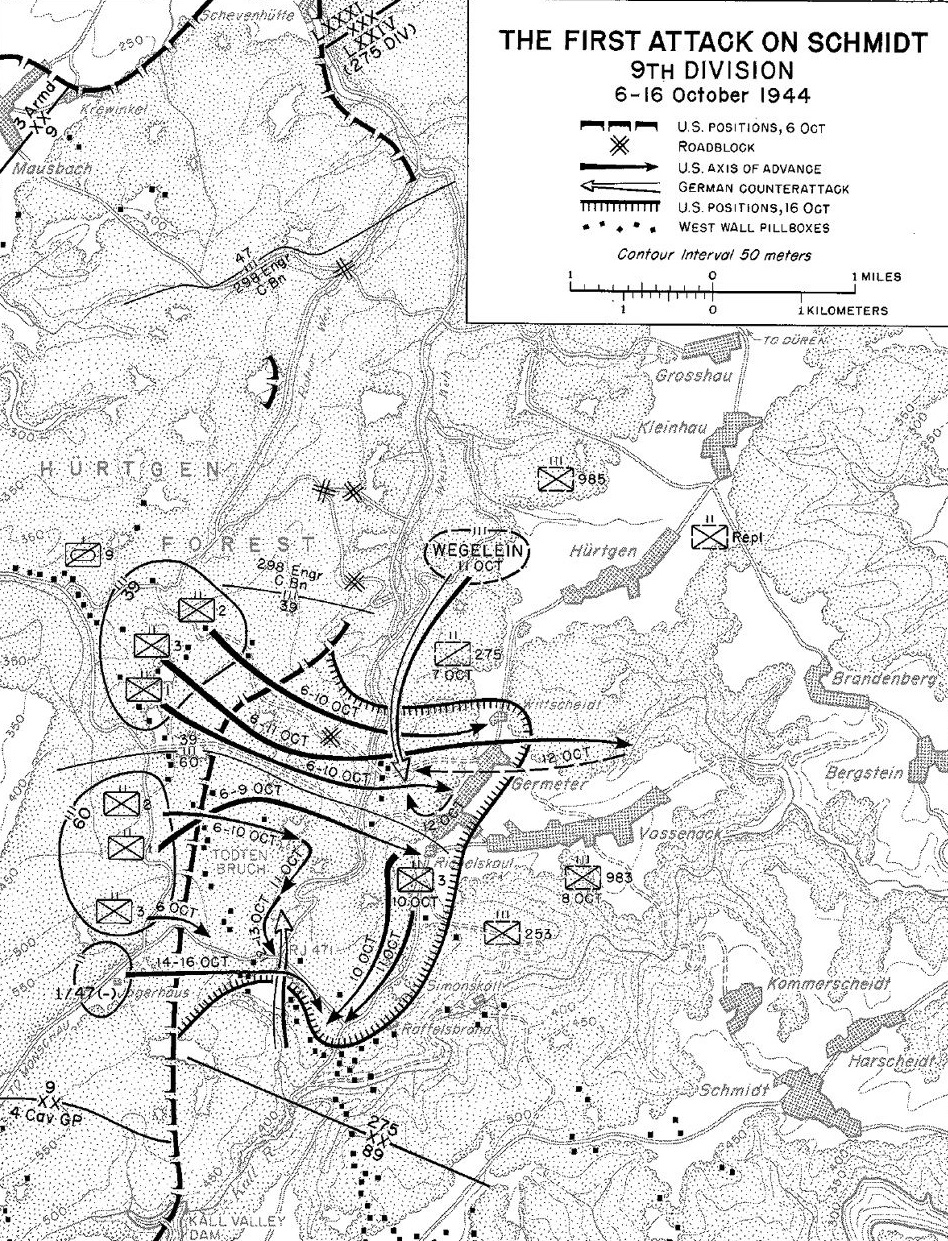

The 9-ID, supported by elements of the 3-AD, moved towards the Huertgen Forest. Unbeknownst to Allied intelligence, on the other side of the forest lay key strategic dams that controlled the level of the Roer River, a major obstacle on the drive to the Rhine River. Named for a nearby village, the Huertgen Forest was a 70-square-mile (181 KM²) region that actually encompassed three major state forests, the Roetgen Forest, the Wenau Forest, and the Huertgen Forest. The forest is an extension of a large wooded region stretching across the German border into Belgium. A ridge system runs through the area from southwest to northeast. The highest parts are over 2100 feet (700 M) in elevation west of Monschau and the lowest area (600 feet above sea level)(200 M) is near Düren. The ridge divides the areas into three separate compartments. Numerous cold, fast-moving streams cut through the area with steep banks. The Weisser Weh creek and the Kall River are two of the major water obstacles in the area. The east-west road networks were limited and the only major north-south routes ran along the edges of the forests. No roads in the Huertgen area could support heavy volumes of traffic. The forest provided almost perfect terrain for defense. Pine trees often grew over a hundred feet tall and blocked out the light.

The 9-ID, supported by elements of the 3-AD, moved towards the Huertgen Forest. Unbeknownst to Allied intelligence, on the other side of the forest lay key strategic dams that controlled the level of the Roer River, a major obstacle on the drive to the Rhine River. Named for a nearby village, the Huertgen Forest was a 70-square-mile (181 KM²) region that actually encompassed three major state forests, the Roetgen Forest, the Wenau Forest, and the Huertgen Forest. The forest is an extension of a large wooded region stretching across the German border into Belgium. A ridge system runs through the area from southwest to northeast. The highest parts are over 2100 feet (700 M) in elevation west of Monschau and the lowest area (600 feet above sea level)(200 M) is near Düren. The ridge divides the areas into three separate compartments. Numerous cold, fast-moving streams cut through the area with steep banks. The Weisser Weh creek and the Kall River are two of the major water obstacles in the area. The east-west road networks were limited and the only major north-south routes ran along the edges of the forests. No roads in the Huertgen area could support heavy volumes of traffic. The forest provided almost perfect terrain for defense. Pine trees often grew over a hundred feet tall and blocked out the light.

The steep ridges and slopes coupled with the lack of sun penetrating through the trees, kept the ground constantly moist and cold. Fog permeated the area. The water table was within a few feet of the surface. An attacker fighting from west to east faced increasing higher ridgelines, thereby nearly always attacking uphill. The forest was originally cultivated as an obstacle to prevent an invasion of Germany from Belgium, and the West Wall tied perfectly into its confines. German engineers sited over three thousand pillboxes, dugouts, and observation posts to exploit the natural terrain features. The pillboxes, many of them circular, were made of steel eight to ten inches thick and covered by a layer of concrete a foot deep. Tank obstacles included ditches covered by pillboxes and hundreds of miles of dragon’s teeth. Passable roads were blocked with cratering charges. The Germans realized the defenses could only delay an attack on Germany, not prevent an invasion.

Critical to the forest’s defenders was Hitler’s need for time to build up forces for his impending Ardennes counter-offensive. The Huertgen Forest was the perfect place to delay the Allies while preparing for his grand assault. T/Sgt George Morgan, 1/22-IR said of the Huertgen: the forest up there is a helluva eerie place to fight … Show me a man who went through the battle … and who says he never had a feeling of fear and I’ll show you a liar. You can’t get protection. You can’t see. You can’t get fields of fire. Artillery slashed the trees like a scythe. Everything is tangled. You can scarcely walk. Everybody is cold and wet, and the mixture of cold rain and sleet keeps falling. It was in this terrain that American armored forces would face their toughest fight.

ARMOR BALANCE

After battling their way from Normandy to the German Border, American tankers developed battle drills and standard operating procedures (SOPs) to defeat the superior German armor. Although outnumbered nearly 10 to 1 in tank production, the principal German tanks were as good as, if not better than, the Allied tanks. The most common tank in the German army was the Mark IV (Pzkpfw IV). Equipped with a high-velocity 75-MM Gun (7.5 CM KwK L/48), it had a top speed of 38 Kmh (21 Mph) and was used throughout the war. Easily produced and modernized, the Mark IV was the backbone of the German Panzer force. The Mark V, better known as the Panther, was one of the best tanks of the war. With sloped, thick armor, and a top speed of 46 Kmh (28.5 Mph), the Panther was highly survivable. It could destroy any enemy tank in existence during 1944 at a combat range of 2000 Meters (2188 Yards) with its high-velocity 75-MM Gun (7.5 CM Kwk L/70). The high muzzle velocity of the Panther’s Gun (1120 M/sec)(3674 Ft/sec) allowed it to penetrate 170-MM of vertical armor, equal to that of the Mark VI-1 Tiger tank’s larger 88-MM Gun.

After battling their way from Normandy to the German Border, American tankers developed battle drills and standard operating procedures (SOPs) to defeat the superior German armor. Although outnumbered nearly 10 to 1 in tank production, the principal German tanks were as good as, if not better than, the Allied tanks. The most common tank in the German army was the Mark IV (Pzkpfw IV). Equipped with a high-velocity 75-MM Gun (7.5 CM KwK L/48), it had a top speed of 38 Kmh (21 Mph) and was used throughout the war. Easily produced and modernized, the Mark IV was the backbone of the German Panzer force. The Mark V, better known as the Panther, was one of the best tanks of the war. With sloped, thick armor, and a top speed of 46 Kmh (28.5 Mph), the Panther was highly survivable. It could destroy any enemy tank in existence during 1944 at a combat range of 2000 Meters (2188 Yards) with its high-velocity 75-MM Gun (7.5 CM Kwk L/70). The high muzzle velocity of the Panther’s Gun (1120 M/sec)(3674 Ft/sec) allowed it to penetrate 170-MM of vertical armor, equal to that of the Mark VI-1 Tiger tank’s larger 88-MM Gun.

The other major tanks facing the Allied armor forces were the well-known Mark VI-1 Tiger with the L/56 88-MM Gun (8.8 CM KwK L/56) and the improved Mark VI-2 Koenigstiger with the L/71 88-MM Gun (8.8 CM KwK L/71). Not nearly as numerous as GIs reported, the Tiger was a squat, angular, yet highly armored tank with a very deadly 88-MM Gun. The heavy firepower and armor protection, however, sacrificed the mobility on which German armor relied for survivability. Well suited for the defense, Tigers would often delay entire companies of Allied armor. In the Huertgen Forest, Tigers were rarely seen but highly effective when used.

The other major tanks facing the Allied armor forces were the well-known Mark VI-1 Tiger with the L/56 88-MM Gun (8.8 CM KwK L/56) and the improved Mark VI-2 Koenigstiger with the L/71 88-MM Gun (8.8 CM KwK L/71). Not nearly as numerous as GIs reported, the Tiger was a squat, angular, yet highly armored tank with a very deadly 88-MM Gun. The heavy firepower and armor protection, however, sacrificed the mobility on which German armor relied for survivability. Well suited for the defense, Tigers would often delay entire companies of Allied armor. In the Huertgen Forest, Tigers were rarely seen but highly effective when used.

The Allies relied on their mass-produced M-4 Sherman Medium Tank and its numerous variants. Over forty thousand Sherman tanks and associated variants were produced during the years 1942-1946, compared with less than fifteen hundred German Tigers produced. The later models of the M-4 were mechanically reliable and highly maneuverable, but the high maneuverability resulted from the tank’s lack of armor protection. Armor thickness varied from 25-MM (1″) to 50-MM (2″) at the frontal slope. The M-4 reached a maximum speed of 38 Kmh (24 Mph) and most models had a 75-MM main gun. Later models had an upgraded 76.2-MM (3″) gun with improved muzzle velocity. However, the majority of the Sherman were under-gunned and under-protected when confronting better German tanks. M-4s relied on their maneuverability and superior numbers to defeat enemy tanks. Mobility was the key to the survival of Allied tanks. The Normandy Hedgerow fighting demonstrated the severe weaknesses of Allied tanks when fighting against both German armor and antitank weapons one-on-one. In addition, tank destroyers based on the M-4 Sherman chassis were used extensively in an assault role. Many were equipped with a larger gun than the tanks, M-10 (3-inch Gun M-7 in Mount M-5), and M-36 (90-MM gun M-3) but the turrets of Allied tank destroyers were open and highly vulnerable to artillery fire and airburst ammunition. Tree bursts, so common in the Huertgen Forest, were extremely devastating to both the vehicles and crews of these combat vehicles.

American armor, so reliant on mobility to survive against superior German tanks, entered the forest initially with the 9-ID. Immediately, the difficult terrain and stubborn resistance of the German forces became obvious. The Normandy hedgerow and later bunker fighting had lent experience to US tankers, but nothing prepared them for the defensive terrain of the Huertgen Forest. The tankers, when teamed up with infantry, became highly skilled at taking out fixed positions. On the dawn of the third day, the enemy developed a counter-attack against Item Co 3/39-IR. The Americans drove off the Germans and fought forward along two trails while under fire from pillboxes. M-4s and tank destroyers forced the bunkers to button up until the infantry could envelop them. However, the obstacles, coupled with an incredible number of mines, often hindered any attempted armored advance. Soldiers from Love Co, hidden by a smokescreen, cleared a minefield through a gap in the dragon’s teeth. But when a tank unit started through the opening, a mine blew up the first one. During the night, German engineers had re-mined the passageway.

American armor, so reliant on mobility to survive against superior German tanks, entered the forest initially with the 9-ID. Immediately, the difficult terrain and stubborn resistance of the German forces became obvious. The Normandy hedgerow and later bunker fighting had lent experience to US tankers, but nothing prepared them for the defensive terrain of the Huertgen Forest. The tankers, when teamed up with infantry, became highly skilled at taking out fixed positions. On the dawn of the third day, the enemy developed a counter-attack against Item Co 3/39-IR. The Americans drove off the Germans and fought forward along two trails while under fire from pillboxes. M-4s and tank destroyers forced the bunkers to button up until the infantry could envelop them. However, the obstacles, coupled with an incredible number of mines, often hindered any attempted armored advance. Soldiers from Love Co, hidden by a smokescreen, cleared a minefield through a gap in the dragon’s teeth. But when a tank unit started through the opening, a mine blew up the first one. During the night, German engineers had re-mined the passageway.

Obviously, fighting in the Huertgen Forest promised to be difficult for infantry and armor alike. The 9-ID was stopped far short of its objective, the key crossroad town of Schmidt. Two regiments of the 9-ID gained about 3000 yards in the forest, but at the cost of forty-five hundred men. Gen Hodges set a target date of November 5 for the renewal of the 1-A’s big push to the Roer and the Rhine. However, before launching his main effort, Hodges knew he still had to secure his right flank. Schmidt was the key, and the V Corps would have to take the town while clearing the forest. The entire main effort fell to one division, the 28-ID. For the first two weeks of November, it would be the only division attacking across the entire 1-A front, affording the German defenders the opportunity to concentrate all their resources. The 28-ID would forever be known as the Bloody Bucket after emerging from the horrific fighting in the Huertgen Forest. Sadly, no key leader realized that the vitally important Roer River Dams lay just beyond the town of Schmidt. The only officer to note their importance was the 9-ID’s G-2, Maj Jack Houston. Houston knew the dams could control a downstream flood should the Allies cross the Roer: Bank overflow and destructive flood waves can be produced by regulating the discharge from the various dams.

Obviously, fighting in the Huertgen Forest promised to be difficult for infantry and armor alike. The 9-ID was stopped far short of its objective, the key crossroad town of Schmidt. Two regiments of the 9-ID gained about 3000 yards in the forest, but at the cost of forty-five hundred men. Gen Hodges set a target date of November 5 for the renewal of the 1-A’s big push to the Roer and the Rhine. However, before launching his main effort, Hodges knew he still had to secure his right flank. Schmidt was the key, and the V Corps would have to take the town while clearing the forest. The entire main effort fell to one division, the 28-ID. For the first two weeks of November, it would be the only division attacking across the entire 1-A front, affording the German defenders the opportunity to concentrate all their resources. The 28-ID would forever be known as the Bloody Bucket after emerging from the horrific fighting in the Huertgen Forest. Sadly, no key leader realized that the vitally important Roer River Dams lay just beyond the town of Schmidt. The only officer to note their importance was the 9-ID’s G-2, Maj Jack Houston. Houston knew the dams could control a downstream flood should the Allies cross the Roer: Bank overflow and destructive flood waves can be produced by regulating the discharge from the various dams.

The attack on Schmidt by the 28-ID initially seemed successful. After negotiating the harrowingly narrow Kall Trail, elements of the 112-IR (Col Carl L. Peterson) secured the towns of Kommerscheidt and Schmidt. The Kall Trail was merely a cart track that supposedly was to serve as the main supply route for the attacking division. Open and exposed at its entrance by the town of Vossenack, the Kall Trail snakes sharply downward, crosses the Kall River, then continues up some very steep ground into the town of Kommerscheidt.  On November 3, two officers from the 20-ECB reconnoitered the Kall Trail and reported it capable of supporting tanks. Col Richard W. Ripple’s 707-TB was attached to the 28-ID. Capt Bruce M. Hostrup (Able Co 707-TB) supported the 112-IR and attempted to move down the Kall Trail. Members of the 112-IR in Schmidt awaited both resupply and armor support when Capt Hostrup led his first platoon down the trail. As the trail descends towards the river, a large rock outcropping juts out in the path. Opposite the rocky outcropping is a sharp drop of approximately fifty feet. As Capt Hostrup’s tank moved down the narrow, muddy trail, it slipped off the edge while trying to maneuver around the rock. Hostrup’s driver managed to keep the tank from careening over the cliff and backed the tank up the trail. Hostrup reported the trail was not passable and no armor would reinforce the soldiers at Schmidt until the trail was improved.

On November 3, two officers from the 20-ECB reconnoitered the Kall Trail and reported it capable of supporting tanks. Col Richard W. Ripple’s 707-TB was attached to the 28-ID. Capt Bruce M. Hostrup (Able Co 707-TB) supported the 112-IR and attempted to move down the Kall Trail. Members of the 112-IR in Schmidt awaited both resupply and armor support when Capt Hostrup led his first platoon down the trail. As the trail descends towards the river, a large rock outcropping juts out in the path. Opposite the rocky outcropping is a sharp drop of approximately fifty feet. As Capt Hostrup’s tank moved down the narrow, muddy trail, it slipped off the edge while trying to maneuver around the rock. Hostrup’s driver managed to keep the tank from careening over the cliff and backed the tank up the trail. Hostrup reported the trail was not passable and no armor would reinforce the soldiers at Schmidt until the trail was improved.