Two additional units were directed to operate in the zone of the interior with the mission of harassing the Japanese lines of communication, particularly in the zone of action of Stilwell’s Chinese forces. One of these units, consisting of several companies of Kachins organized by Col Ray Peers, Commanding Officer of OSS Detachment 101, was already on the ground with hide-outs throughout the Kumon Range all the way from Shingbwiang to Myltkyina. The other unit, a new Wingate LRPG, was scheduled to be glider-transported to three landing areas between Bhamo and Indaw (except for one column which was to proceed on foot from Ledo to Linkin).

Two additional units were directed to operate in the zone of the interior with the mission of harassing the Japanese lines of communication, particularly in the zone of action of Stilwell’s Chinese forces. One of these units, consisting of several companies of Kachins organized by Col Ray Peers, Commanding Officer of OSS Detachment 101, was already on the ground with hide-outs throughout the Kumon Range all the way from Shingbwiang to Myltkyina. The other unit, a new Wingate LRPG, was scheduled to be glider-transported to three landing areas between Bhamo and Indaw (except for one column which was to proceed on foot from Ledo to Linkin).

According to plan, Stilwell’s 38th Division pushed off towards Shingbwiang in late October, fought timidly at first but gradually developed confidence, and had actually won a few minor victories (at the expense of the Jap 13th Division outpost units) by the time the 22nd Division joined it in January 1944. The fall of Maingkwan and Walawbum on March 7 marked the debut of the Merrill’s Marauders who blocked the Japs in the rear while the 22nd and 38th steamrollered the enemy front and flanks. The same period, however, found the British in an extremely embarrassing position on both of its fronts. On the Arakan Front, the XV Corps’ 5th and 7th Indian Divisions had crossed the frontier in December 1942 in a repetition of the ill-fated January 1943 scheme of maneuver, that is, in two columns, one on each side of the Mayu Range. Buthidaung held out against the 7th Division, but Maungdaw fell to the 5th Division on January 1, 1944. The gain was short-lived.

According to plan, Stilwell’s 38th Division pushed off towards Shingbwiang in late October, fought timidly at first but gradually developed confidence, and had actually won a few minor victories (at the expense of the Jap 13th Division outpost units) by the time the 22nd Division joined it in January 1944. The fall of Maingkwan and Walawbum on March 7 marked the debut of the Merrill’s Marauders who blocked the Japs in the rear while the 22nd and 38th steamrollered the enemy front and flanks. The same period, however, found the British in an extremely embarrassing position on both of its fronts. On the Arakan Front, the XV Corps’ 5th and 7th Indian Divisions had crossed the frontier in December 1942 in a repetition of the ill-fated January 1943 scheme of maneuver, that is, in two columns, one on each side of the Mayu Range. Buthidaung held out against the 7th Division, but Maungdaw fell to the 5th Division on January 1, 1944. The gain was short-lived.

Elements of the Jap 55th Division, employing the same tactics which had so demoralized the original defenders of Burma in 1942, slipped several divisions between the 7th Division and its left flank guard, the 81st West African Division. Before the British were aware of the Jap strategy, the enemy forces had seized Taung Bazaar and, shortly thereafter, the Ngakyedauk Pass, thus encircling the 7th Division. Thanks to airdrop, the 7th managed to hold out while the XV Corps Commander, Gen Christison, sent additional troops to its rescue.

The 5th Division swung north to attack the Ngakyedauk Pass from the east; the 36th Division and the 26th Division marched south from the reserve area in Chittagong, the former joining forces with the 5th division effort, the latter pressing an attack on the eastern side of the pass. Contact with the 7th Division was finally gained by the capture of the pass on February 23. Thereafter the British forces shifted south again and captured Razabil and the tunnels between Razabil and Buthidaung when a serious penetration of the IV Corps area on the northwest Burma border called for the transfer of the 5th and 7th Divisions to the Imphal Front.

As of the middle of April 1944, therefore, Gen Alexander Christison, with only one division, the 25th, to replace the two lost to him, and with the monsoon ready to break in a few weeks, decided to consolidate the ground gained. He ordered the 81st West Africans to close into the west and established them on a defense line from the Taung Bazaar to the 26th Division positions at Sinzweya. The 25th Division occupied the link from the western extent of the 26th at the tunnels on to the east through Razabil and Maungdaw to the sea. The second Arakan Campaign was over.

As of the middle of April 1944, therefore, Gen Alexander Christison, with only one division, the 25th, to replace the two lost to him, and with the monsoon ready to break in a few weeks, decided to consolidate the ground gained. He ordered the 81st West Africans to close into the west and established them on a defense line from the Taung Bazaar to the 26th Division positions at Sinzweya. The 25th Division occupied the link from the western extent of the 26th at the tunnels on to the east through Razabil and Maungdaw to the sea. The second Arakan Campaign was over.

Why had the 7th and 5th Divisions been so suddenly diverted from the Arakan to the 14th Army (specifically the IV Corps) front? The 14th Army had obviously gotten itself into trouble. In carrying out its phase of the Capital Plan, the 14th Army’s IV Corps, consisting of the 23rd, 17th, and 20th Divisions, had pushed forward in March 1944, advancing cautiously and with an old-school-tie strategy for a survey of the ground of future maneuver.

Why had the 7th and 5th Divisions been so suddenly diverted from the Arakan to the 14th Army (specifically the IV Corps) front? The 14th Army had obviously gotten itself into trouble. In carrying out its phase of the Capital Plan, the 14th Army’s IV Corps, consisting of the 23rd, 17th, and 20th Divisions, had pushed forward in March 1944, advancing cautiously and with an old-school-tie strategy for a survey of the ground of future maneuver.

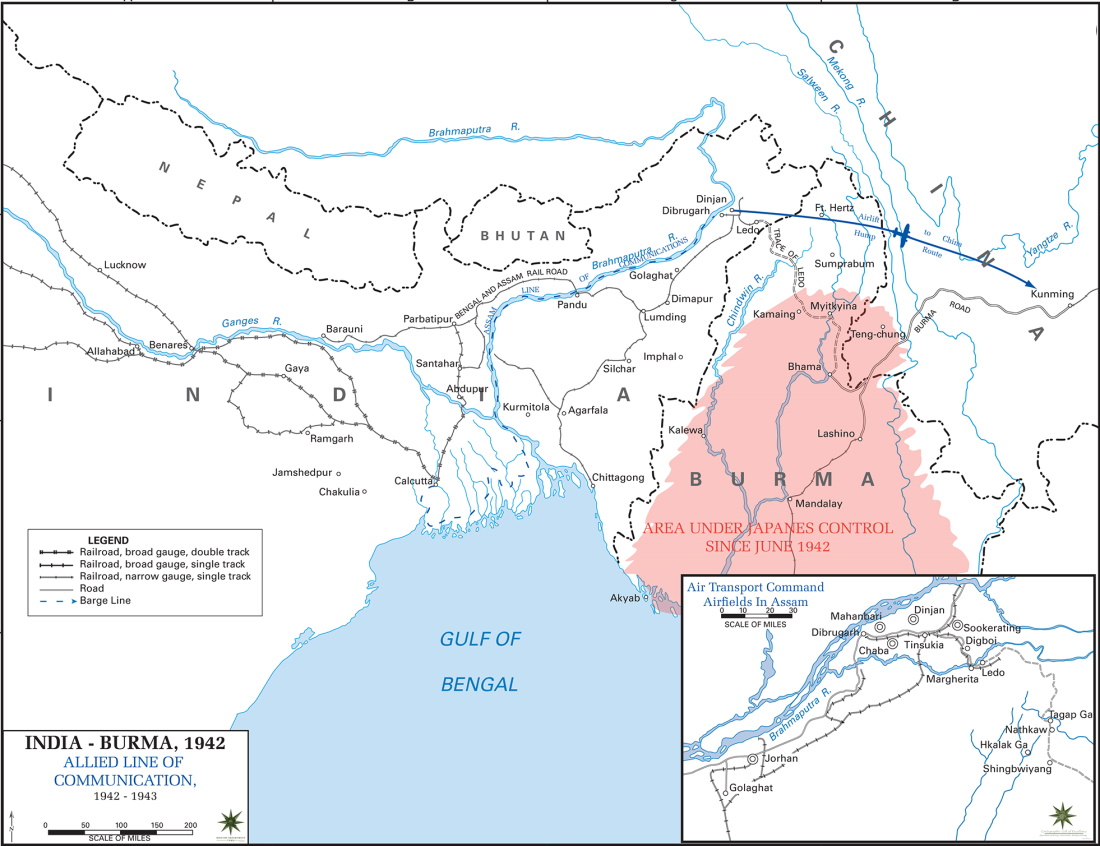

But the Japs struck first. Three Jap flying columns, totaling three divisions, but off the 17th Indian Division at Tiddtra; threatened the 20th Division rear at Tamu; and, by-passing the 23rd Indian Division at Ukhrul, appeared to be well on the way to Imphal and Kohima, the seizure of which would be tantamount to slamming the back doer on all the allied troops then operating in north Burma. In other words, the middle of March found the Burma Campaign hanging by the thinnest of threads. Stilwell was undoubtedly doing a great deal of worrying during this period of threatened Jap interdiction of the very important Bengal and Assam railroad, the supply lifeline of his Chinese and American troops in Burma; but he kept his fingers crossed and ordered his troops to continue their advance.

But the Japs struck first. Three Jap flying columns, totaling three divisions, but off the 17th Indian Division at Tiddtra; threatened the 20th Division rear at Tamu; and, by-passing the 23rd Indian Division at Ukhrul, appeared to be well on the way to Imphal and Kohima, the seizure of which would be tantamount to slamming the back doer on all the allied troops then operating in north Burma. In other words, the middle of March found the Burma Campaign hanging by the thinnest of threads. Stilwell was undoubtedly doing a great deal of worrying during this period of threatened Jap interdiction of the very important Bengal and Assam railroad, the supply lifeline of his Chinese and American troops in Burma; but he kept his fingers crossed and ordered his troops to continue their advance.

On one point all fronts were not in unanimous agreement for the first time during the campaign: the British had to act positively and aggressively, and they couldn’t afford to fumble this ball. Too much was at stake; half measures would not suffice.

On one point all fronts were not in unanimous agreement for the first time during the campaign: the British had to act positively and aggressively, and they couldn’t afford to fumble this ball. Too much was at stake; half measures would not suffice.

The first step was to save the committed divisions of the IV Corps from annihilation. With the aid of the 23rd Division, the 17th Division finally fought its way out of the encirclement at Tiddim. Both divisions withdrew to Imphal where they

The first step was to save the committed divisions of the IV Corps from annihilation. With the aid of the 23rd Division, the 17th Division finally fought its way out of the encirclement at Tiddim. Both divisions withdrew to Imphal where they

were joined by the 20th Division. In order to relieve the beleaguered battalions of mixed troops at Kohima, all other commitments in the CBI area were momentarily shelved.

were joined by the 20th Division. In order to relieve the beleaguered battalions of mixed troops at Kohima, all other commitments in the CBI area were momentarily shelved.

Sufficient planes from the American ATC in Assam were diverted

Sufficient planes from the American ATC in Assam were diverted  from the Hump supply service to transport the 5th Division, with all its impedimenta, from the Arakan to Kohima.

from the Hump supply service to transport the 5th Division, with all its impedimenta, from the Arakan to Kohima.

The XXXIII Corps was ordered to march from the center of India to Kohima without delay. Lastly, the 7th Indian Division was flown up from Arakan early in April. Thus the 14th Army’s two corps fell the responsibility of stopping the Japs, the IV Corp at Imphal and the XXXIII Corps, plus the 7th Division, at Kohima. Hit for the first time by a determined British effort, and with the monsoon arriving in May to unleash buckets of water from the skies, the Japs were in the end no match for troops that could be supplied by air when ground routes turned to quagmires; but it was a long, desperate uphill fight for the 14th Army. By mid-May, the sieges of Imphal and Kohima had been lifted and the Japs had passed to the defensive. By mid-July Ukhrul had been retaken by the British; by Aug 19, the last Jap resistance units had been ejected from India.

The XXXIII Corps was ordered to march from the center of India to Kohima without delay. Lastly, the 7th Indian Division was flown up from Arakan early in April. Thus the 14th Army’s two corps fell the responsibility of stopping the Japs, the IV Corp at Imphal and the XXXIII Corps, plus the 7th Division, at Kohima. Hit for the first time by a determined British effort, and with the monsoon arriving in May to unleash buckets of water from the skies, the Japs were in the end no match for troops that could be supplied by air when ground routes turned to quagmires; but it was a long, desperate uphill fight for the 14th Army. By mid-May, the sieges of Imphal and Kohima had been lifted and the Japs had passed to the defensive. By mid-July Ukhrul had been retaken by the British; by Aug 19, the last Jap resistance units had been ejected from India.

Pursuit, now became the 14th Army’s primary mission, and, for the first time, was undertaken despite the monsoon, though at the reduced rate dictated by muddy roads and trails and the exhausted condition of the battle-scarred troops. Stilwell meanwhile had forged steadily ahead, probably, however, with one eye fixed anxiously on the 14th Army front. After a grueling 70-mile march in rugged mountain rain forests, the Marauders descended upon Myitkyina and seized the airstrip before the surprised Japs could put up an effective defense.

However, the inability of the Marauders to follow up their initial success (due to exhaustion and sickness) resulted in the hurried commitment of green American and Chinese troops who fled in panic in their first encounter with the enemy garrison of Myitkyina town. The Japs, taking advantage of the temporary confusion, brought in reinforcements and dug themselves in sufficient strength to withstand the Chinese-American attacks until Aug 3. Thereafter, Stilwell, too, went over to the pursuit but also on a limited scale due to the necessity for regrouping and refitting his forces. The first seven months of 1944 were the decisive months in the campaign to retake Burma; and August, as the month in which the British, Chinese, and Americans stood victorious on the north-central, northwest, and southwest battlegrounds, was the turning point in the campaign.

However, the inability of the Marauders to follow up their initial success (due to exhaustion and sickness) resulted in the hurried commitment of green American and Chinese troops who fled in panic in their first encounter with the enemy garrison of Myitkyina town. The Japs, taking advantage of the temporary confusion, brought in reinforcements and dug themselves in sufficient strength to withstand the Chinese-American attacks until Aug 3. Thereafter, Stilwell, too, went over to the pursuit but also on a limited scale due to the necessity for regrouping and refitting his forces. The first seven months of 1944 were the decisive months in the campaign to retake Burma; and August, as the month in which the British, Chinese, and Americans stood victorious on the north-central, northwest, and southwest battlegrounds, was the turning point in the campaign.

The crucial battles, which by odd coincidence had taken place practically simultaneously on three fronts, swept away the misconceptions, prejudices, and archaic military doctrines which had stood in the way of a vigorous concerted attack on the enemy ever since the grim days of 1942. Now, for the first time, all military leaders in CBI were willing to accept a few fundamental truths, namely: that the Chinese and Indians, when properly led, could match the Japs man for man and gun for gun, and beat them; that hoary tradition to the contrary, troops could, and should, fight on through the monsoon rather than move back into the hills and face the prospect of fighting over the same ground again with the return of each dry season; that the logistical headache imposed by hyper-secret agencies was one known as the OG (Operational Group) Command. This command, with headquarters located in Washington, was charged with the responsibility for the recruiting and training of military personnel, both officer and enlisted, for assignment to small, well-integrated platoons whose mission would consist of long-range penetrations into enemy areas for purposes of destruction, straight reconnaissance, or a combination of both. Whatever the specific mission of a specific OG platoon, however, it was manifest that the platoon survival would depend exclusively on the intelligence, resourcefulness, and courage of the men comprising it; where it was to go, there would be no supporting arms, no friendly adjacent units, and no reserves to succor it when it got into trouble.

The crucial battles, which by odd coincidence had taken place practically simultaneously on three fronts, swept away the misconceptions, prejudices, and archaic military doctrines which had stood in the way of a vigorous concerted attack on the enemy ever since the grim days of 1942. Now, for the first time, all military leaders in CBI were willing to accept a few fundamental truths, namely: that the Chinese and Indians, when properly led, could match the Japs man for man and gun for gun, and beat them; that hoary tradition to the contrary, troops could, and should, fight on through the monsoon rather than move back into the hills and face the prospect of fighting over the same ground again with the return of each dry season; that the logistical headache imposed by hyper-secret agencies was one known as the OG (Operational Group) Command. This command, with headquarters located in Washington, was charged with the responsibility for the recruiting and training of military personnel, both officer and enlisted, for assignment to small, well-integrated platoons whose mission would consist of long-range penetrations into enemy areas for purposes of destruction, straight reconnaissance, or a combination of both. Whatever the specific mission of a specific OG platoon, however, it was manifest that the platoon survival would depend exclusively on the intelligence, resourcefulness, and courage of the men comprising it; where it was to go, there would be no supporting arms, no friendly adjacent units, and no reserves to succor it when it got into trouble.

For that reason, the recruiting board made every effort to appraise candidates accurately via personal interviews, mental and psychological tests, and physical fitness tests. Since long-range planning by the OG Operations Officer envisaged the use of such platoons in Yugoslavia, Greece, Italy, Holland, Belgium, France, China, Thailand, Malaya, Bunna, and the East Indies, the assignment of a recruit to a particular platoon was based mainly upon the foreign language requirement for that platoon, which, of course, in turn, was based upon the foreign country in which that platoon was expected to operate. The foreign country, in its turn, determined whether a platoon was to be trained for parachute invasion or amphibious invasion. Units scheduled for operations in Yugoslavia, for example, were given parachute training, whereas Greek OG’s were trained amphibiously.

For that reason, the recruiting board made every effort to appraise candidates accurately via personal interviews, mental and psychological tests, and physical fitness tests. Since long-range planning by the OG Operations Officer envisaged the use of such platoons in Yugoslavia, Greece, Italy, Holland, Belgium, France, China, Thailand, Malaya, Bunna, and the East Indies, the assignment of a recruit to a particular platoon was based mainly upon the foreign language requirement for that platoon, which, of course, in turn, was based upon the foreign country in which that platoon was expected to operate. The foreign country, in its turn, determined whether a platoon was to be trained for parachute invasion or amphibious invasion. Units scheduled for operations in Yugoslavia, for example, were given parachute training, whereas Greek OG’s were trained amphibiously.

The OG Platoon which eventually arrived in Burma was trained originally for employment in the East Indies. The color of the native population, lack of definite pro-American reception parties, the distance of the islands from friendly air bases, and the presence of strong Jap ack-ack batteries and interceptor squadrons in these islands dictated a submarine-LCR (Yugoslavia, Greece, Italy, Holland, Belgium, France, China, Thailand, Malaya, Bunna, and the East Indies) combination as the only sound means of penetration. Accordingly, the platoon was given amphibious training on Catalina Island before leaving the United States. In June of 1944, it arrived in Galle, Ceylon where the LCR landing and launching techniques were subjected to surf conditions generally heavier than any that might be encountered anywhere in the Indies. Towards the end of July two circumstances arose that completely changed the original objectives of the GO Platoon.

First, OSS Headquarters in Kandy, Ceylon, received orders from Washington to rescind all plans for operations in the East Indies and to concentrate instead on Burma, Malaya, and Thailand. Second, the XV Corps’ plans for renewed and greatly intensified attacks on the Arakan Front created a definite need for a number of small, specially trained, highly skilled amphibious units.

First, OSS Headquarters in Kandy, Ceylon, received orders from Washington to rescind all plans for operations in the East Indies and to concentrate instead on Burma, Malaya, and Thailand. Second, the XV Corps’ plans for renewed and greatly intensified attacks on the Arakan Front created a definite need for a number of small, specially trained, highly skilled amphibious units.

Reasons for the reconnaissance on the Arakan Front have already been stated in previous paragraphs. But why the need for amphibious units? The answer to this question lay, of course, in the missions assigned to the XV Corps. These were briefly as follows: (1) The seizure of forwarding airstrips to support the British 14th Army troops who would be out of the economical air-support radius of North Burma airbases by the time they reached Mandalay; (2) The seizure of an advanced naval base suitable as a staging area for an amphibious assault on Rangoon; (3) The isolation and destruction of the Japanese forces defending the Arakan in order to prevent their diversion to the 14th Army front. (Jap Arakan coastal forces consisted of the 55th Division plus Coast Artillery Units).

Mission (1) implied the seizure of Akyab whose all-weather airfield could be repaired and put into operation in a short time despite the heavy bombings it had received from American and British planes. Since Akyab was an island whose best beachhead lay in its northwest corner 8 water miles from Foul Point (the tip of the Mayu Peninsula), an amphibious operation was indicated. Ramree Island, 60 miles farther to the south offered ground for several fighter strips, but it was more important as the objective for the Mission 2.

Mission (2) Its harbor, and the channel between it and the mainland, offered protected anchorages for all types of craft and ships, from LCT to light cruisers and 3000-ton freighters. Finally, due to the nature of the terrain and the tactics to be employed, the accomplishment of Mission 3.

Mission (3) necessitated amphibious landings on the Arakan Coast. Gen Christison, XV Corps’ Commanding Officer, taking a leaf from Stilwell’s book of strategy, decided to use the 81st and 82nd West African Divisions and the 25th Indian Division as a frontal attacking force and to give the 26th Indian Division the role of the maneuvering element, committed to wide flanking movements which would place it in the Jap rear. Wide flanking movements in the Arakan area southeast of Akyab could be made in only one direction, however, and that was to the west and, hence, by way of the sea.

Analysis of the missions assigned to him had therefore prompted Gen Christison to accumulate a variety of amphibious units under his command. One of his organic divisions, the 26th Indian, was, at this very time (Sept.), undergoing amphibious training on the coast of India.

The 3rd SS (Special Service Commando) Brigade, already well-versed in amphibious assaults, was placed under XV Corps command early in September after a period of jungle training in Ceylon. Three motor launch flotillas, each composed of six 110-foot Families, had been placed in direct corps support. In addition to the conventional army units, there were a number of small, highly specialized teams that were scheduled to play an important part in the forthcoming operations.

Among these were the following: two Special Boat Sections, each consisting of two officers and ten enlisted men, and six Mark 1A-1 Kayaks (a collapsible, two-man, canvas canoe, propelled by means of double-bladed paddles) for employment on pre-invasion reconnaissance missions; the ‘COPPS’, combined army and navy personnel organized into balanced technical teams capable of making pre-invasion hydrographic studies of tentative beachheads, and limited terrain studies of the areas immediately behind the beaches; D-Force, a unit with lithe equipment (recordings of battle noises, amplifiers, firecrackers, which simulate machine gun bursts, shell whistles, etc) and personnel (a regular T/O Battalion of Indian Infantry) necessary to deceive the enemy as to the location of the main landing effort; E-Force, an air-sea rescue unit which operated a flotilla of small, fast P-boats.