During the Second World War, the United States fought as a member of the largest military coalition ever formed. Across the world, millions of American soldiers, sailors, and airmen joined with the fighting forces of other nations to defeat the Axis Powers. As they did so, they wrote many new chapters in the history of coalition warfare and combined operations. Of those chapters, none illustrates the benefits and the difficulties inherent in this type of warfare more vividly than does the story of what happened to the Merrill’s Marauders in the Northern part of Burma.

During the Second World War, the United States fought as a member of the largest military coalition ever formed. Across the world, millions of American soldiers, sailors, and airmen joined with the fighting forces of other nations to defeat the Axis Powers. As they did so, they wrote many new chapters in the history of coalition warfare and combined operations. Of those chapters, none illustrates the benefits and the difficulties inherent in this type of warfare more vividly than does the story of what happened to the Merrill’s Marauders in the Northern part of Burma.

Merrill’s Marauders is the popular name given to the US Army’s 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional). For radio communications, the 5307 was also known by its code name Galahad, a regiment-sized unit organized and trained for long-range penetration groups (LRPG) behind enemy lines in Japanese-held Burma during World War II. The 5307 had a short history. Recruitment for the unit began on Sep 1, 1943, and it was disbanded on Aug 10, 1944. The unit did not reach India until Oct 31, 1943, and was only in combat in Burma from the end of Feb 1944 to the first days of Aug. But during that period, the 5307 established an impressive record. In fighting against Japanese forces and in its constant struggle against disease, leeches, insects, harsh terrain, and the weather, the Marauders earned the following Distinguished Unit Citation:

The 5307 (C)(P) Galahad was the first United States ground combat force to meet the enemy in World War II on the continent of Asia. After a series of successful engagements in the Hukawng and Mogaung Valleys of North Burma, in March and April 1944, the unit was called on to lead a march over jungle trails through extremely mountainous terrain against stubborn resistance in an attack on Myitkyina. The unit proved equal its task, overcame all the obstacles put in its way by the enemy, and the weather and, after a brilliant operation May 17, 1944, seized the airfield at Myitkyina, an objective of great tactical importance in the campaign, and assisted in the capture of Myitkyina on August 3, 1944. The successful accomplishment of this mission marks the 5307th Composite Unit (Prov) as an outstanding combat force and reflects great credit on Allied Arms.

ground combat force to meet the enemy in World War II on the continent of Asia. After a series of successful engagements in the Hukawng and Mogaung Valleys of North Burma, in March and April 1944, the unit was called on to lead a march over jungle trails through extremely mountainous terrain against stubborn resistance in an attack on Myitkyina. The unit proved equal its task, overcame all the obstacles put in its way by the enemy, and the weather and, after a brilliant operation May 17, 1944, seized the airfield at Myitkyina, an objective of great tactical importance in the campaign, and assisted in the capture of Myitkyina on August 3, 1944. The successful accomplishment of this mission marks the 5307th Composite Unit (Prov) as an outstanding combat force and reflects great credit on Allied Arms.

The accomplishments of the 5307, however, were achieved at a tremendous human cost. The total strength of the unit at the beginning of its operations was 2997 officers and men. Because some of the men received rear-echelon assignments such as parachute riggers and kickers (i.e., men who kicked bundles of supplies out of transport aircraft during airdrops), the actual number of men who set out on the first mission on Feb 24, 1944, was 2750. After this operation ended with the capture of Walawbum on Mar 7, about 2500 remained to carry on. The unit’s second mission, from Mar 12 to April 9, resulted in 67 men killed and 379 evacuated because of wounds or illness.

The accomplishments of the 5307, however, were achieved at a tremendous human cost. The total strength of the unit at the beginning of its operations was 2997 officers and men. Because some of the men received rear-echelon assignments such as parachute riggers and kickers (i.e., men who kicked bundles of supplies out of transport aircraft during airdrops), the actual number of men who set out on the first mission on Feb 24, 1944, was 2750. After this operation ended with the capture of Walawbum on Mar 7, about 2500 remained to carry on. The unit’s second mission, from Mar 12 to April 9, resulted in 67 men killed and 379 evacuated because of wounds or illness.

Thereby reduced to about 2000 men, the 5307 was augmented by Chinese and native Kachin soldiers for its third mission, the operation to take the Myitkyina airfield, which began on Apr 28. Only 1310 Americans reached this objective, and between May 17, and Jun 1, the large majority of these men, most of whom were suffering from disease, were evacuated by air to rear area hospitals. By the time the town of Myitkyina was taken, only about 200 of the original Galahad force was present. A week after Myitkyina fell, on Aug 10, 1944, the 5307, utterly worn out and depleted, was disbanded.

Why did the 5307 ends up this way? Why was the first US combat unit to fight on the Asian continent driven until it suffered over 80 percent casualties and experienced what an inspector general’s report described as an almost complete breakdown of morale in the major portion of the unit? Col Charles N. Hunter, the second-ranking, and sometimes only ranking, officer of the unit during its existence, expected heavy casualties from the start. In briefings at the War Department in Sep 1943, he was told that casualties were projected to reach 85 percent. But at the end of the 5307’s campaign, he still felt that the unit had been badly misused and had suffered unnecessarily.

Why did the 5307 ends up this way? Why was the first US combat unit to fight on the Asian continent driven until it suffered over 80 percent casualties and experienced what an inspector general’s report described as an almost complete breakdown of morale in the major portion of the unit? Col Charles N. Hunter, the second-ranking, and sometimes only ranking, officer of the unit during its existence, expected heavy casualties from the start. In briefings at the War Department in Sep 1943, he was told that casualties were projected to reach 85 percent. But at the end of the 5307’s campaign, he still felt that the unit had been badly misused and had suffered unnecessarily.

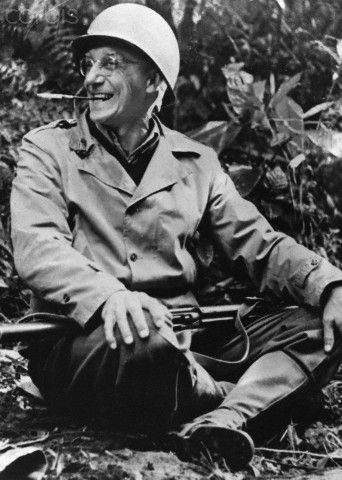

Years later, in a book about the 5307 titled Galahad, he placed the blame for what happened to the unit squarely on the personality and personal ambition of the campaign’s commander, Gen Joseph ‘Vinegar Joe’ Stilwell: Galahad Force was the most beat upon, most misunderstood, most mishandled, most written about, most heroic, and yet most unrewarded regimental sized unit that participated in World War II. That it was expendable was understood from its inception; what was not understood and has never been adequately explained, is why it was expended to bolster the ego of an erstwhile Theater Commander such as Vinegar Joe Stilwell.

Col Hunter’s account of events is compelling and moving. It is easy to understand why he felt that Stilwell had sacrificed the 5307 to bolster his ego. Yet in assessing the criticism of Stilwell, it must not be forgotten that, during this period, he was acting under orders from above and was under pressure to achieve specific military objectives set by the US Joint Chiefs of Staff (USJCoS). In addition, Stilwell had to cope with the problems created in the China-Burma-India Theater (CBI) by coalition warfare and the need to conduct combined operations.

Col Hunter’s account of events is compelling and moving. It is easy to understand why he felt that Stilwell had sacrificed the 5307 to bolster his ego. Yet in assessing the criticism of Stilwell, it must not be forgotten that, during this period, he was acting under orders from above and was under pressure to achieve specific military objectives set by the US Joint Chiefs of Staff (USJCoS). In addition, Stilwell had to cope with the problems created in the China-Burma-India Theater (CBI) by coalition warfare and the need to conduct combined operations.

In this theater, more than in any other theater in which the USA fought during World War II, the problems peculiar to coalition warfare were present. While the coalition partners of the USA in the CBI, China and Great Britain, helped augment US resources and contributed significantly to the war against Japan, they also created situations that forced Stilwell to lay heavy burdens on the 5307. Ultimately, it was not so much that the 5307 was a victim of Stilwell’s ego, but that both the 5307 and Stilwell were affected by the exigencies and requirements of coalition warfare and combined operations.

Coalitions, by nature, are somewhat delicate creations. They are formed by sovereign nations who join together to provide the strength of numbers for the pursuit of a common goal or goals. But national differences in strategic aims can diminish the force a coalition can bring to bear at a particular place and time. Also, differences in military capabilities, warfighting doctrine, cultural traditions, social values, and language can make it difficult for coalition forces to achieve unity of effort in combined operations. All of these debilitating conditions were present in the CBI as the three coalition partners sought to fight the war against Japan in ways consistent with their national objectives. Interestingly, because of these different objectives, neither Great Britain, the former colonial ruler of Burma, nor China, who would regain a land link to the outside world if northern Burma were retaken, were as committed to retaking northern Burma as was the USA. These different viewpoints had created tensions in the coalition since the start of the war. In 1944, lack of agreement about what to do in Burma contributed greatly to what happened to the 5307.

The British did not give a high priority to retaking northern Burma because of doubts about Chinese military capabilities and the belief that reestablishing a land link to China would not make much difference in the war against Japan. Great Britain’s primary focus remained on Europe and the Mediterranean area. The British did not want to commit large forces in retaking Burma, and at the great war conferences of 1943 they consistently argued either for reducing the scale of operations to be undertaken in Burma or for bypassing Burma altogether and going to Sumatra.

The British did not give a high priority to retaking northern Burma because of doubts about Chinese military capabilities and the belief that reestablishing a land link to China would not make much difference in the war against Japan. Great Britain’s primary focus remained on Europe and the Mediterranean area. The British did not want to commit large forces in retaking Burma, and at the great war conferences of 1943 they consistently argued either for reducing the scale of operations to be undertaken in Burma or for bypassing Burma altogether and going to Sumatra.

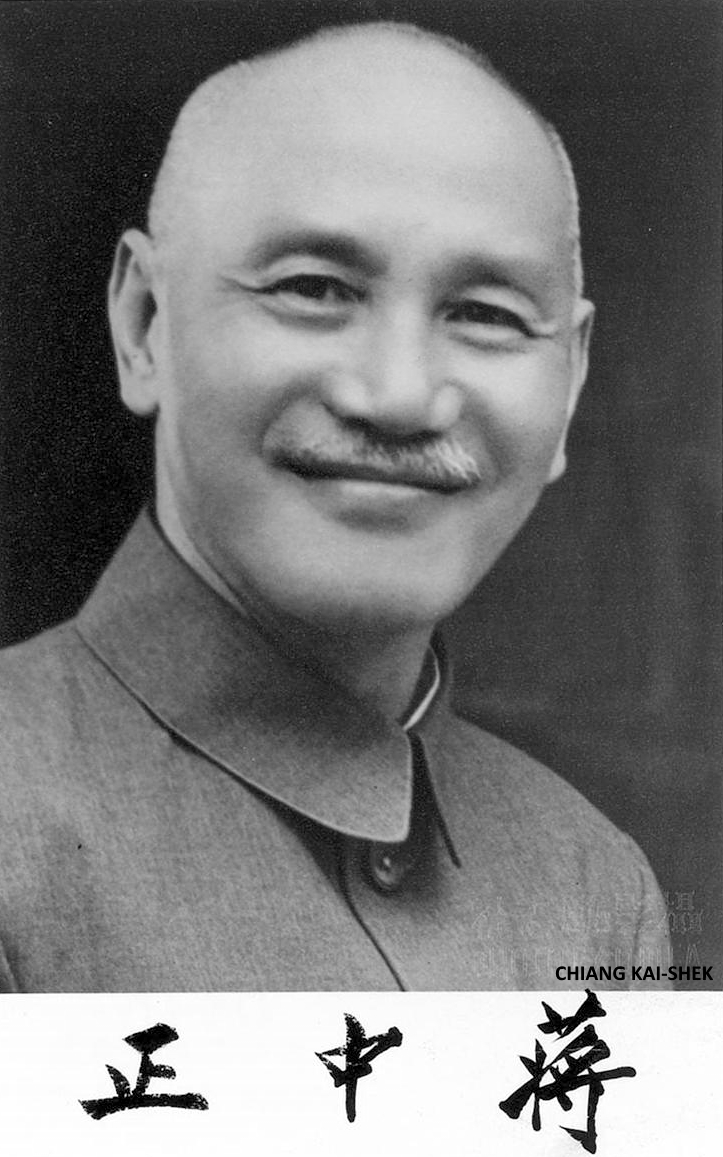

China’s position was that of Chiang Kai-Shek, president and commander of the Chinese Army. His government was weak and faced many internal challenges, especially from the Communists. He did not want to see his military forces consumed in battles with the Japanese because he would then have fewer troops to support him in internal disputes. He welcomed American aid and sought more. Yet he was also Leery of training and assistance programs because they might strengthen his domestic rivals. As Stilwell told Gen George C. Marshall in mid-1943, Chiang did not want the regime to have a large efficient ground force for fear that its commander would inevitably challenge his position as China’s leader. Chiang’s fundamental approach to the war with Japan was to adopt a defensive posture and let the United States win it for him, preferably with air power. He was more interested in expanding the airlift from India to China than in reestablishing a Land link.

In contrast to Great Britain and China, the United States took an activist position on Burma and on China itself. As opposed to Britain’s negative view of what China could offer, the US saw China’s geographic position and large manpower pool as great assets. America believed that it was possible to improve the Chinese Army so that it could make a positive contribution to the coming offensive against Japan. Even before becoming an active belligerent, the US, in May 1941, had begun sending Lend-lease material to China.

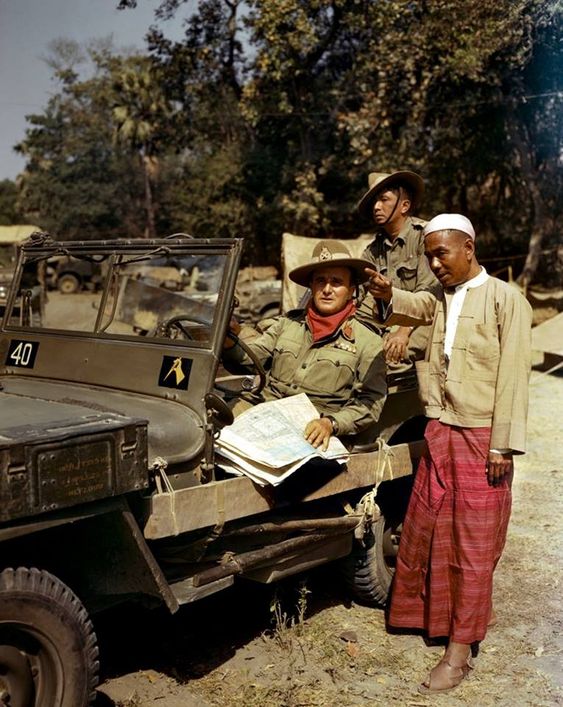

In Jul 1941, the American Military Mission to China had been established to help China procure weapons to fight its war against Japan and to train personnel to use them. Stilwell had been sent to China in Feb 1942 to expand this effort, with specific orders to increase the effectiveness of the US assistance to the Chinese government for the prosecution of the war and to assist in improving the combat efficiency of the Chinese Army. After the Japanese occupied Burma in the spring of 1942 and cut China’s last land line of communication to the outside world, the US made reestablishing that land link a high priority. Overland transportation was seen as essential to providing more aid to China.

At the coalition war conferences convened during 1943, the concept of Burma as the route to China led the US to stress continually the need to retake Burma. At the Casablanca Conference, held on Jan 14-23, the American Joint Chiefs of Staff put an offensive to retake Burma high on the conference agenda and obtained British agreement to conduct the operation in the winter of 1943-44. At the Trident Conference held in Washington in May 1943, the US agreed with the British that developments in the war in Europe made it advisable to scale back this offensive so that it would just cover northern Burma. At American insistence, however, it was also agreed that a land link to China through this area must be gained during the coming winter dry season.

Three months later, the Quadrant Conference, held in Quebec Canada on Aug 19-24, reaffirmed the need for restoring land communications with China. Looking into the future, US and UK planners envisioned Chinese forces and US forces in the Pacific converging on the Canton-Hong Kong area. Once emplaced there, these forces would drive north to liberate North China and establish staging areas for operations against Japan. The year 1947 was set for operations against Japan proper. Retaking northern Burma and constructing the Ledo Road south through Myitkyina to the old Burma Road was a fundamental part of this strategic plan, in  that the road would bring in supplies for the Chinese forces that would move toward Canton from the northwest.

that the road would bring in supplies for the Chinese forces that would move toward Canton from the northwest.

The Quadrant Conference also led to the US decision to send a combat unit, Galahad, to the China-Burma-India Theater to participate in the upcoming winter offensive. The US Army had long had a large number of support units in the theater. In late Dec 1942, the US 823-EAB (Aviation Engineer) had taken over construction from the British of the part of the Ledo Road that lay in India. US medical personnel, quartermaster units, and air corps units also had steadily increased in number during 1942 and 1943. But despite Stilwell’s requests (since Jul 1942) for a US combat corps or at least a division, no fighting units had been sent to the theater. Now, one was going, perhaps to demonstrate the seriousness of America’s interest in retaking northern Burma. Or, perhaps, it was being sent as a reward to Gen Orde C. Wingate for his aggressiveness, which the United States had found in short supply among the British generals in India.

The Quadrant Conference also led to the US decision to send a combat unit, Galahad, to the China-Burma-India Theater to participate in the upcoming winter offensive. The US Army had long had a large number of support units in the theater. In late Dec 1942, the US 823-EAB (Aviation Engineer) had taken over construction from the British of the part of the Ledo Road that lay in India. US medical personnel, quartermaster units, and air corps units also had steadily increased in number during 1942 and 1943. But despite Stilwell’s requests (since Jul 1942) for a US combat corps or at least a division, no fighting units had been sent to the theater. Now, one was going, perhaps to demonstrate the seriousness of America’s interest in retaking northern Burma. Or, perhaps, it was being sent as a reward to Gen Orde C. Wingate for his aggressiveness, which the United States had found in short supply among the British generals in India.

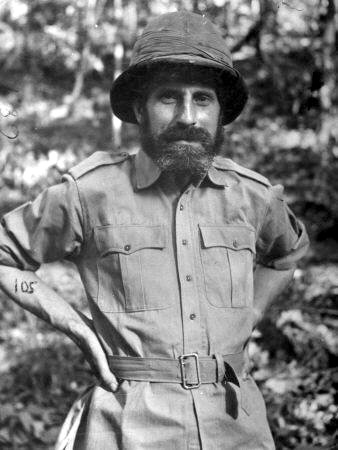

Wingate was an innovative thinker, who before being assigned to the British forces in Burma in early 1942 had gained experience in guerrilla warfare in Palestine and Ethiopia. Analyzing the tactics used by the Japanese in capturing Burma, he determined that the key to their success was superior mobility. Repeatedly, Japanese units had moved quickly along small trails in the jungle to outflank and envelop road-bound Allied units. Wingate’s answer to this tactical challenge was to free Allied units from reliance on roads.

in capturing Burma, he determined that the key to their success was superior mobility. Repeatedly, Japanese units had moved quickly along small trails in the jungle to outflank and envelop road-bound Allied units. Wingate’s answer to this tactical challenge was to free Allied units from reliance on roads.

He proposed forming highly mobile units, Long Range Penetration Groups (LRPGs), that would be inserted deep behind the Japanese lines by gliders and transport aircraft and supplied from the air. It was assumed that this method of supply would allow the LRPGs to outmaneuver the Japanese and attack their lines of communications at will.

Following the cancellation of an offensive into Burma scheduled for March 1943, Gen Archibald Wavell Supreme Commander, India, had authorized Wingate to carry out a raid into Burma to test the validity of Wingate’s theories. Despite incurring high losses and effecting little lasting damage, the raid captured the public imagination with its daring. Prime Minister Winston Churchill invited Wingate to London for a personal briefing and then took him to Quebec to attend the Quadrant Conference. There, Wingate won approval from the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCoS) for an expanded program of LRPG operations in Burma.

Following the cancellation of an offensive into Burma scheduled for March 1943, Gen Archibald Wavell Supreme Commander, India, had authorized Wingate to carry out a raid into Burma to test the validity of Wingate’s theories. Despite incurring high losses and effecting little lasting damage, the raid captured the public imagination with its daring. Prime Minister Winston Churchill invited Wingate to London for a personal briefing and then took him to Quebec to attend the Quadrant Conference. There, Wingate won approval from the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCoS) for an expanded program of LRPG operations in Burma.

Gen Georges C. Marshall (CoS) and Gen Henry H. Arnold, (CG USAAC), were so impressed by Wingate’s presentation that they agreed to send approximately 3000 American infantrymen to India to form an LRPG Group code-named Galahad. They also decided to send two of the Air Corps’ best airmen, Col Philip G. Cochran and Col J. R. Alison to India to activate and command 1st Air Commando, a custom-made aggregation of liaison aircraft, light bombers, fighters, gliders and transports that would support Wingate’s LRPG operations.

In May 1942, Col J.R. Alison and his close friend Col Philip G. Cochran were called into the office of USAAC, Gen Henry Hap Arnold, in the recently completed Pentagon to discuss who would command a new air group to be deployed to Burma called Project 9. Both officers recommended the other. Arnold, in an administrative move that was, if not unique, then certainly rare in the military, officially made them co-commanders of the unit, telling them: to hell with the paperwork; go out and fight.