In the thick of battle, the soldier is busy doing his job. He has the knowledge and confidence that his Job is part of a unified plan to defeat the enemy, but he does not have time to survey a campaign from a fox hole. If he should be wounded and removed behind the lines, he may have even less opportunity to learn what place he and his unit had in the larger fight.

In the thick of battle, the soldier is busy doing his job. He has the knowledge and confidence that his Job is part of a unified plan to defeat the enemy, but he does not have time to survey a campaign from a fox hole. If he should be wounded and removed behind the lines, he may have even less opportunity to learn what place he and his unit had in the larger fight.

American Forces in Action is a series of documents prepared by the War Department especially for the information of wounded men. It will show these soldiers, who have served their country so well, the part they and their comrades played in achievements which do honor to the record of the United States Army. Merrill’s Marauders is an account of the operations of the 5307 Composite Unit (Provisional) in north Burma from February to May 1944. The Marauders’ effort was part of a coordinated offensive the Allied reconquest of north Burma. Details of the offensive are summarized briefly to set the operations of the 5307 within the larger framework.

On Aug 10, 1944, the 5307th Composite Unit was reorganized as the 475th Infantry Regiment. The combat narrative is based mainly on interviews conducted by the historian of the 5307 after the operation and on information furnished the Historical Branch, G-2, War Department, by the Commanding General and several members of the unit. Few records were available because the Marauders restricted their files in order to maintain mobility while they were operating behind the Japanese lines. During the second mission, a Japanese artillery shell scored a direct hit on the mule carrying the limited quantity of records and maps kept by the unit headquarters. During the third mission, the heavy rains made the preservation of papers impossible for more than a day or two. The unit’s intelligence officer was killed at Myitkyina, and his records were washed away before they could be located. The manuscript was submitted by the Historical Section of the India-Burma Theater.

The 5307 Composite Unit (Provisional) (Code Name: Galahad) of the Army of the United States was organized and trained for (LRPG) Long Range Penetration Group behind enemy lines in Japanese-held Burma. Commanded by Gen Frank D. Merrill, its 2997 officers and men became popularly known as Merrill’s Marauders. From February to May 1944, the operations of the Marauders were closely coordinated with those of the 22nd Chinese Division and the 38th Chinese Division in a drive to recover northern Burma and clear the way for the construction of the Ledo Road, which was to link the Indian railhead at Ledo with the old Burma Road to China.

The Marauders were foot soldiers who marched and fought through jungles and over mountains from the Hukawng Valley in northwestern Burma to Myitkyina on the Irrawaddy River. In 5 major and 30 minor engagements they met and defeated the veteran soldiers of the 18th Japanese Division. Operating in the rear of the main forces of the Japanese, they prepared the way for the southward advance of the Chinese by disorganizing supply lines and communications. The climax of the Marauders’ operations was the capture of the Myitkyina airfield, the only all-weather strip in northern Burma. This was the final victory of the 5307 Composite Unit, which was disbanded in August 1944.

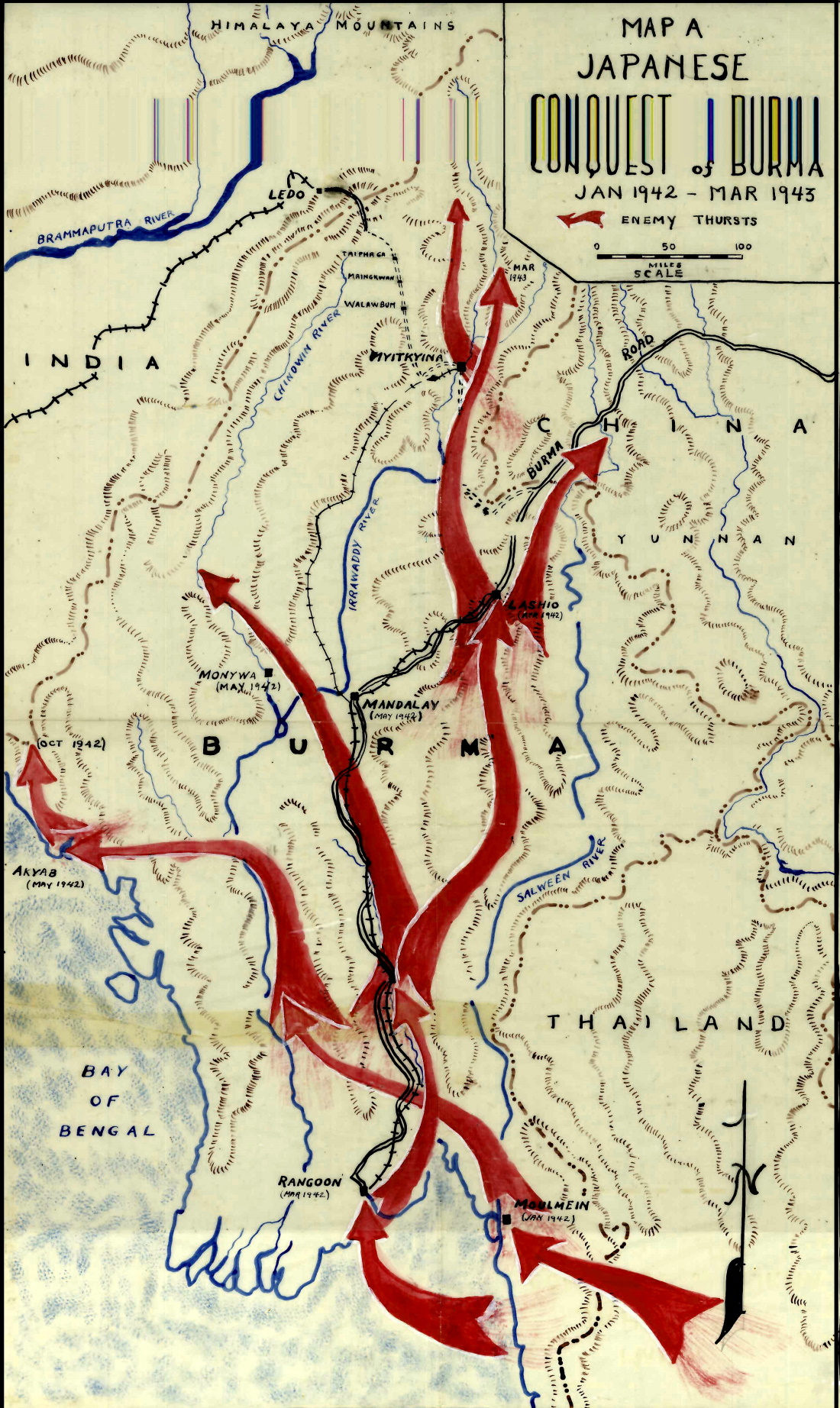

The War in Burma, Jan 1942 – Mar 1943

Burma had been conquered by the Japanese 2 years before the Marauders’ operations. During the 6 months between Dec 1941 and May 1942, the enemy had overrun the Philippines, much of Oceania, all of the Netherlands East Indies, all of the Malay Peninsula, and almost all of Burma. In the Pacific Ocean, his advance threatened communications between the United States and Australasia. On the Asiatic mainland, his occupation of Burma menaced India, provided a bulwark against counterattack from the west, cut the last land route for supply of China, and added Burma’s raw materials to the resources of an empire already rich.

For the conquest of Burma, the Japanese had concentrated two divisions in southern Thailand. In mid-January 1942, they struck Moulmein, which fell on the 30th. British, Indian, and Burmese forces, aided by the Royal Air Force and the American Volunteer Group, resisted the Salween and Sittang river crossings but were overwhelmed by enemy superiority in numbers, equipment, and planes. Rangoon, the capital and principal port, was taken on Mar 8. The Japanese then turned north into two columns. One division pushed up the Sittang where Chinese forces under Gen Joseph W. Stilwell were coming in to defend the Burma Road. The other Japanese division pursued the Indian and Burmese forces up the Irrawaddy Valley.

On Apr 1-2, the enemy took Toungoo on the Sittang and Prome on the Irrawaddy. From Yenangyaung, north of Prome, a column pushed westward and on May 4, took the port of Akyab on the Bay of Bengal. The conquest of southern Burma was complete. A third enemy column of two divisions, which had landed at Rangoon on Apr 12, was now attacking on the east from the Shan States into the upper Salween Valley and driving rapidly northward to take Lashio, the junction of the rail and highway sections of the Burma Road. Mandalay, completely outflanked, was evacuated by its Chinese defenders and occupied by the Japanese on May 1.

From Lashio, the Japanese pushed up the Salween Valley well into the Chinese province of Yunnan. In north-central Burma they sent a small patrol northward along the Irrawaddy almost to Fort Hertz, and to the west they took Kalewa on the Chindwin. The main remnants of Gen Stilwell’s forces retired from north Burma to India by way of Shingbwiyang, while British, Burmese, and Indian survivors withdrew up the valley of the Chindwin and across the Chin Hills. The Allied withdrawal was made on foot, for no motor road or railway connected India with Burma. When the monsoon rains came in June the Japanese held all of Burma except for fringes of mountain, jungle, and swamp on the north and west. Gen Stilwell grimly summarized the campaign: I claim we got a hell-of-a-beating. We got run out of Burma, and it is as humiliating as hell. I think we ought to find out what caused it, go back, and retake it. But this counter-offensive could not start at once, and the Japanese were able to make further advances in the next fighting season.

From Lashio, the Japanese pushed up the Salween Valley well into the Chinese province of Yunnan. In north-central Burma they sent a small patrol northward along the Irrawaddy almost to Fort Hertz, and to the west they took Kalewa on the Chindwin. The main remnants of Gen Stilwell’s forces retired from north Burma to India by way of Shingbwiyang, while British, Burmese, and Indian survivors withdrew up the valley of the Chindwin and across the Chin Hills. The Allied withdrawal was made on foot, for no motor road or railway connected India with Burma. When the monsoon rains came in June the Japanese held all of Burma except for fringes of mountain, jungle, and swamp on the north and west. Gen Stilwell grimly summarized the campaign: I claim we got a hell-of-a-beating. We got run out of Burma, and it is as humiliating as hell. I think we ought to find out what caused it, go back, and retake it. But this counter-offensive could not start at once, and the Japanese were able to make further advances in the next fighting season.

At the end of October, they pushed northwestward along the coast from Akyab toward Bengal. Approximately a month later British forces counter-attacked strongly along this same coast, but their gains could not be held, and the Japanese force reached the frontier of Bengal. In February of the next year, the enemy began to drive northward from Myitkyina. He had covered some 75 air miles by early March and was closing in on Sumprabum, threatening to occupy the whole of northern Burma and to destroy the British-led Kachin and Gurkha levies which had hitherto dominated the area. The Allies were in no position to stop this advance. Their regular forces had retired from the area to India in May and were separated from the Japanese by densely forested mountain ranges and malarial valleys. The enemy was apparently secure in Southeast Asia. The question of the moment was whether his advance would halt along the Burma border or would continue into India.