After a day of heavy fighting that failed to take Inkangahtawng, the 2/5307 commander decided that he had no choice but to withdraw eastward toward Manpin. As this withdrawal was taking place on Mar 25, the danger presented by the reinforced Japanese battalion striking north from Kamaing became clear. If this force reached Auche before the 2/5307 and the 3/5307 did, this portion of the Marauders Group would be cut off from its route of withdrawal northward to Nhpum Ga.

After a day of heavy fighting that failed to take Inkangahtawng, the 2/5307 commander decided that he had no choice but to withdraw eastward toward Manpin. As this withdrawal was taking place on Mar 25, the danger presented by the reinforced Japanese battalion striking north from Kamaing became clear. If this force reached Auche before the 2/5307 and the 3/5307 did, this portion of the Marauders Group would be cut off from its route of withdrawal northward to Nhpum Ga.

To slow the Japanese advance, two platoons were sent to block the two trails running north from Kamaing. These units successfully fought a series of delaying actions on Mar 26, 27, and 28 that allowed the main body to pass through Auche on the 27 and the 28. With the 2/5307 and the 3/5307 retiring from the Kamaing Road, Stilwell decided that this was an opportune time to travel to Chungking to meet with Chiang Kai-Shek. As he flew off to China on Mar 27, however, events were taking another dramatic turn. A Japanese sketch showing their intention to continue moving north through Auche to threaten the left flank of the 22nd Division was brought into Stilwell’s HQs.

Since the Japanese could not be allowed to complete this maneuver, the two Marauders Battalions were ordered to stop them. In response to this order, Merrill placed the 2/5307 on the high ground at Nhpum Ga and deployed the 3/5307 to defend an airstrip at Hsamshingyang, some three miles to the north. The division of his force was required because Merrill had over 100 wounded who needed to be evacuated by air and the Nhpum Ga heights dominated the airstrip. The 3/5307 was also to provide a reserve force and be responsible for keeping the trail between Hsamshingyang and Nhpum Ga open. The stage was now set for one of the most difficult periods in the short history of the 5307 Composite Unit. The 2/5307 had hardly finished building its defensive perimeter when the Japanese began attacking on Mar 28. This same day, Merrill suffered a heart attack and Col Charles N. Hunter relieved him. Then, on Mar 31, the Japanese succeeded in cutting the trail between Hsamshingyang and Nhpum Ga. For more than a week, the Japanese repulsed all attempts to reopen the trail and kept the 2/5307 isolated except for airdrops. During this time, repeated Japanese artillery barrages and infantry assaults inflicted serious casualties on the 2/5307.

Since the Japanese could not be allowed to complete this maneuver, the two Marauders Battalions were ordered to stop them. In response to this order, Merrill placed the 2/5307 on the high ground at Nhpum Ga and deployed the 3/5307 to defend an airstrip at Hsamshingyang, some three miles to the north. The division of his force was required because Merrill had over 100 wounded who needed to be evacuated by air and the Nhpum Ga heights dominated the airstrip. The 3/5307 was also to provide a reserve force and be responsible for keeping the trail between Hsamshingyang and Nhpum Ga open. The stage was now set for one of the most difficult periods in the short history of the 5307 Composite Unit. The 2/5307 had hardly finished building its defensive perimeter when the Japanese began attacking on Mar 28. This same day, Merrill suffered a heart attack and Col Charles N. Hunter relieved him. Then, on Mar 31, the Japanese succeeded in cutting the trail between Hsamshingyang and Nhpum Ga. For more than a week, the Japanese repulsed all attempts to reopen the trail and kept the 2/5307 isolated except for airdrops. During this time, repeated Japanese artillery barrages and infantry assaults inflicted serious casualties on the 2/5307.

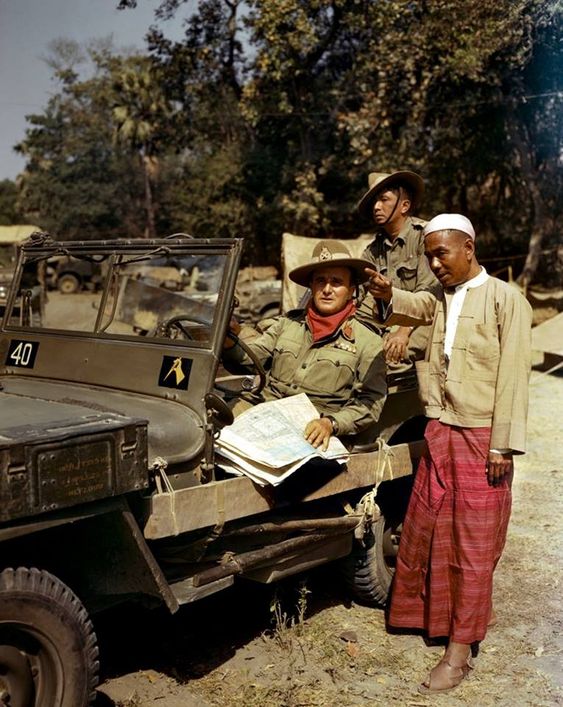

(Photo & Caption Source – marauder.org) Hsamshingyang, Burma, Apr or late Mar, 1944. The international character of the 5307 Composite Unit (Provisional) (Galahad) is shown by groups. Rear Row L to R; Sgt Harold Stevenson (Irish). Pfc Stephen Komar (Ukrainian). Pvt Geo D. Altman (German). Sgt Carl Hamelic (Dutch). Pvt Jose L. Montoya (Spanish). Capt A. E. Quinn (Anglo-Burmese). Capt D.G. Wilson (Anglo Burmese). Pfc Joc Yuele (Italian). Third Row L to R; Pvt Kai L. Wong (Chinese). S/Sgt C.N. Dulien (Polish). Cpl Perry E. Johnson (Swedish). Pfc Louis 0. Pederomo (Cuban). T/Sgt Jack Crowly (American). Second Row L to R; T/Sgt Russell Hill (English). Sgt Werner Katz (Jewish). Sgt Miles Elson (Swedish). S/Sgt F. Wonsowitz (Polish). Sgt Edw, Kucera (Bohemian). Cpl Bernard Martin (French). Sgt Wilbur Smalley (English Irish). Front Rows L to R; Father James Stewart (Irish). N’Ching Gam (Kachin). Li Yaw Tank (Maru). Purta Singly (Gurhka) and Hpakawn Zau Mun (Atzi).

(Photo & Caption Source – marauder.org) Hsamshingyang, Burma, Apr or late Mar, 1944. The international character of the 5307 Composite Unit (Provisional) (Galahad) is shown by groups. Rear Row L to R; Sgt Harold Stevenson (Irish). Pfc Stephen Komar (Ukrainian). Pvt Geo D. Altman (German). Sgt Carl Hamelic (Dutch). Pvt Jose L. Montoya (Spanish). Capt A. E. Quinn (Anglo-Burmese). Capt D.G. Wilson (Anglo Burmese). Pfc Joc Yuele (Italian). Third Row L to R; Pvt Kai L. Wong (Chinese). S/Sgt C.N. Dulien (Polish). Cpl Perry E. Johnson (Swedish). Pfc Louis 0. Pederomo (Cuban). T/Sgt Jack Crowly (American). Second Row L to R; T/Sgt Russell Hill (English). Sgt Werner Katz (Jewish). Sgt Miles Elson (Swedish). S/Sgt F. Wonsowitz (Polish). Sgt Edw, Kucera (Bohemian). Cpl Bernard Martin (French). Sgt Wilbur Smalley (English Irish). Front Rows L to R; Father James Stewart (Irish). N’Ching Gam (Kachin). Li Yaw Tank (Maru). Purta Singly (Gurhka) and Hpakawn Zau Mun (Atzi).

Disease, inadequate nourishment, fatigue, and stress also took their toll. On Apr 7, a tired and hungry 1/5307 arrived in Hsamshingyang after a grueling march from the Shaduzup area, and the next day they added their strength (only 250 men from the battalion were physically able to join in the effort to another attempt by the 3/5307 to break through to the 2/5307. Slight progress was made on Apr 8, and then, suddenly, during the afternoon of Apr 9, the Japanese withdrew.  The battle had been won, but the cost to the 5307 had been high. In fighting at the attempted roadblock at Inkanghtawng, seven men had been killed and twelve wounded. The Nhpum Ga battle, moreover, resulted in fifty-two men killed and 302 wounded. In addition, seventy-seven sick soldiers were evacuated after the fighting ended. After the battle at Nhpum Ga, the 5307 was given several days’ rest, and new outfits of clothing were issued. In addition, nutritious ten-in-one rations were delivered, and mail was received for the first time in two months. But baths and new clothes could not alter reality; the unit was worn out: terribly exhausted; suffering extensively and persistently from malaria, diarrhea, and both bacillary and amebic dysentery; beset by festering skin lesions, infected scratches, and bites; depleted by 500 miles of marching on packaged rations, the Marauders were sorely stricken. They had lost 700 men killed, wounded, disabled by non-battle injuries, and, most of all, sick. Over half of this number had been evacuated from 2/5307 alone. Many remaining in the regiment were more or less ill, and their physical condition was too poor to respond quickly to medication and rest.

The battle had been won, but the cost to the 5307 had been high. In fighting at the attempted roadblock at Inkanghtawng, seven men had been killed and twelve wounded. The Nhpum Ga battle, moreover, resulted in fifty-two men killed and 302 wounded. In addition, seventy-seven sick soldiers were evacuated after the fighting ended. After the battle at Nhpum Ga, the 5307 was given several days’ rest, and new outfits of clothing were issued. In addition, nutritious ten-in-one rations were delivered, and mail was received for the first time in two months. But baths and new clothes could not alter reality; the unit was worn out: terribly exhausted; suffering extensively and persistently from malaria, diarrhea, and both bacillary and amebic dysentery; beset by festering skin lesions, infected scratches, and bites; depleted by 500 miles of marching on packaged rations, the Marauders were sorely stricken. They had lost 700 men killed, wounded, disabled by non-battle injuries, and, most of all, sick. Over half of this number had been evacuated from 2/5307 alone. Many remaining in the regiment were more or less ill, and their physical condition was too poor to respond quickly to medication and rest.

Clearly, at this point, the Galahad force was facing a mounting health crisis that threw the unit’s ability to undertake another mission into question. Combat losses, even including the heavy losses suffered in the fighting at Nhpum Ga, were below projected levels. Non-battle casualties that required evacuation, however, were much higher than expected and were rising rapidly. In February and March, they totaled 200. In April, alone, they numbered 304, as the effects of the harsh battlefield conditions at Nhpum Ga began to be felt. At Nhpum Ga, the 5307 had suffered because it was ordered to fight in a static defensive role for which it was neither trained nor equipped. Then the heat and diseases of tropical Burma combined to add to the unit’s misery: the deserted villages of Hsamshingyang and Nphum Ga became saturated with insect pests and disease organisms produced in decaying animals and men, foul water, and fecal wastes. Mental health, too, was imperiled for the troops on the hill as their casualties accumulated on the spot, visible and pitiable testaments to the waste of battle and the fate that might befall the entire force. Scrub typhus appeared. Malaria recurrences flared up ominously. The diarrheas and dysentery became rampant. Chronic disabilities took acute forms. When the siege lifted, the men nearly collapsed with exhaustion and sickness.

Outwardly, the 5307 seemed to recover as it rested and received good food and good medical treatment at Hsamshingyang, but the exhaustion and illness of the soldiers could not be overcome with just a few days rest. Many, if not most, of the soldiers, were beginning to suffer from malnutrition due to extended use of the K-rations that, as Hunter notes, were a near-starvation diet, designed to be consumed only under emergency conditions when no other food could be made available. Also, numerous soldiers suffered from chronic diseases that were sure to flare up again as soon as they began to experience anxiety and exert themselves. The consensus among the men of the 5307 was that the unit needed to go into rainy-monsoon quarters somewhere to recuperate and reorganize for the next season. This was not to happen. Higher authorities wanted Myitkyina taken. Stilwell was motivated by his own deep desire to take the airfield and the town before the onset of the summer rainy season.

Outwardly, the 5307 seemed to recover as it rested and received good food and good medical treatment at Hsamshingyang, but the exhaustion and illness of the soldiers could not be overcome with just a few days rest. Many, if not most, of the soldiers, were beginning to suffer from malnutrition due to extended use of the K-rations that, as Hunter notes, were a near-starvation diet, designed to be consumed only under emergency conditions when no other food could be made available. Also, numerous soldiers suffered from chronic diseases that were sure to flare up again as soon as they began to experience anxiety and exert themselves. The consensus among the men of the 5307 was that the unit needed to go into rainy-monsoon quarters somewhere to recuperate and reorganize for the next season. This was not to happen. Higher authorities wanted Myitkyina taken. Stilwell was motivated by his own deep desire to take the airfield and the town before the onset of the summer rainy season.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff had also made their position clear, the minimum objective in north Burma was the seizing and holding of Myitkyina this dry season. Furthermore, developments within the coalition at the strategic-political and operational levels were putting pressure on Stilwell to act. Since the tactical situation and the nature of the forces under his command meant that Myitkyina could only be reached and attacked by a task force led by the 5307, the die was cast. The Merrill’s Marauders would be ordered to undertake the third mission. The pressure to take Myitkyina that Stilwell felt from the coalition partners was the result of new British and Chinese support for his north Burma campaign.

Because that support was in large measure a response to US pressure, he knew that he could not slacken his efforts. When Boatner had met with President Roosevelt on Feb 18, while on his mission to Washington for Stilwell, Roosevelt had expressed his frustration about the situation in Burma. He had told Boatner that he was more dissatisfied with the progress of the war there than in any other place. In response, Boatner had urged the president to ask the British and Chinese to be more aggressive in Burma. This the president did. He expressed his views to Churchill, and in a letter delivered to Chiang Kai-Shek on Mar 20, Roosevelt’s diplomatically praised the accomplishments of the Ledo Force while asking for action by the Y-Force to take advantage of the Japanese dispersal, your Chinese Corps on the Ledo Road has administered a serious setback to the Japanese with heavy losses to the enemy in men, ground, and prestige. It is a magnificent outfit. Gen Stilwell was able to employ the US 5307 Galahad to considerable advantage and altogether the heavy reverse administered to the crack 18th Japanese Division represents an important victory. I am communicating my views to you at length and in considerable detail in the hope that you will give orders to the commander of your Yunnan force to cooperate in developing what appears to be an opportunity. I send my very warm regards. Signed Roosevelt.

Because that support was in large measure a response to US pressure, he knew that he could not slacken his efforts. When Boatner had met with President Roosevelt on Feb 18, while on his mission to Washington for Stilwell, Roosevelt had expressed his frustration about the situation in Burma. He had told Boatner that he was more dissatisfied with the progress of the war there than in any other place. In response, Boatner had urged the president to ask the British and Chinese to be more aggressive in Burma. This the president did. He expressed his views to Churchill, and in a letter delivered to Chiang Kai-Shek on Mar 20, Roosevelt’s diplomatically praised the accomplishments of the Ledo Force while asking for action by the Y-Force to take advantage of the Japanese dispersal, your Chinese Corps on the Ledo Road has administered a serious setback to the Japanese with heavy losses to the enemy in men, ground, and prestige. It is a magnificent outfit. Gen Stilwell was able to employ the US 5307 Galahad to considerable advantage and altogether the heavy reverse administered to the crack 18th Japanese Division represents an important victory. I am communicating my views to you at length and in considerable detail in the hope that you will give orders to the commander of your Yunnan force to cooperate in developing what appears to be an opportunity. I send my very warm regards. Signed Roosevelt.

Chiang Kai-Shek responded to Roosevelt’s Letter on Mar 27, the day before he met with Stilwell in Chungking. In his reply, he again expressed his regrets about conditions in China that made it impossible to send the Y-Force into Burma, but he did make a major concession, saying, I have decided to dispatch to India by air as many troops in Yunnan as can be spared in order to reinforce the troops in Ledo, thus enabling the latter to carry on their task of defeating the enemy.

This letter did not satisfy Roosevelt. On Apr 3, he sent Chiang a more strongly worded message about the need to send the Y-Force into action immediately. Roosevelt stated plainly that the United States had been training and equipping the Yoke Force for just such an opportunity and that, if it did not move now, this effort could not be justified. On Apr 10, Marshall followed up this message with a message to Stilwell telling him to stop lend-lease shipments to the Y-Force. To forestall this move, on Apr 14, the Chinese agreed to order an offensive by the Y-Force into Burma. In mid-April, therefore, Stilwell knew that Roosevelt had personally intervened with Churchill and Chiang Kai-Shek to gain more support for his campaign. He also had received the benefits of that intervention.

During his meetings in Chungking on Mar 28 and Mar 29, the Chinese had agreed to send two divisions, the 14th, and the 50th Chinese Divisions, to north Burma. Then, roughly two weeks later, they agreed to send the Y-Force into Burma. If, after all of this had been accomplished, Stilwell did nothing, he would be wasting Roosevelt’s efforts and embarrassing the president in front of the Chinese. Stilwell also felt that he would be squandering the support he had been receiving from the British, especially Gen Slim. The British support was extremely important because of the major Japanese offensive into eastern India that had been launched on Mar 8, just two days after Stilwell and Mountbatten had met to settle their misunderstandings. The offensive had been anticipated, but its strength had not. Three Japanese divisions advanced to surround Imphal and Kohima, and by the beginning of April, it seemed possible that the Japanese might cut the lines of communication supporting both Stilwell’s forces and the airfields used to fly supplies into China. Stilwell had recognized the seriousness of the threat and, after returning from Chungking, had decided to offer Gen Slim the use of his 38th Division even though he knew that this would mean the end of his advance and all hope of reaching Myitkyina before the monsoon rains came.

The British support was extremely important because of the major Japanese offensive into eastern India that had been launched on Mar 8, just two days after Stilwell and Mountbatten had met to settle their misunderstandings. The offensive had been anticipated, but its strength had not. Three Japanese divisions advanced to surround Imphal and Kohima, and by the beginning of April, it seemed possible that the Japanese might cut the lines of communication supporting both Stilwell’s forces and the airfields used to fly supplies into China. Stilwell had recognized the seriousness of the threat and, after returning from Chungking, had decided to offer Gen Slim the use of his 38th Division even though he knew that this would mean the end of his advance and all hope of reaching Myitkyina before the monsoon rains came.

But to his great surprise and relief, when he had met with Slim, Mountbatten, and Gen W.D.A. Lentaigne, Brig Wingate’s successor, at Jorhat, India, on Apr 3, to discuss the situation, the British had stood firmly behind him. Slim had told him that he could keep the 38th Division and also the two new Chinese divisions that were arriving. Slim had also guaranteed that any possible interruption of the line of communication to Ledo would not exceed ten days and that the LRPGs (Chindits) flown into central Burma in early March would continue to support Stilwell’s campaign in the north instead of shifting their attention to the west. At the Jorhat meeting, Slim and Stilwell also discussed the possibility of reaching Myitkyina ahead of the rains. Since Slim was leaving him in control of the three Chinese Army divisions, the 22nd, 30th, and the 38th; plus the two new divisions, the 14th, and the 50th; and Galahad-Stilwell was optimistic that he still could do it.

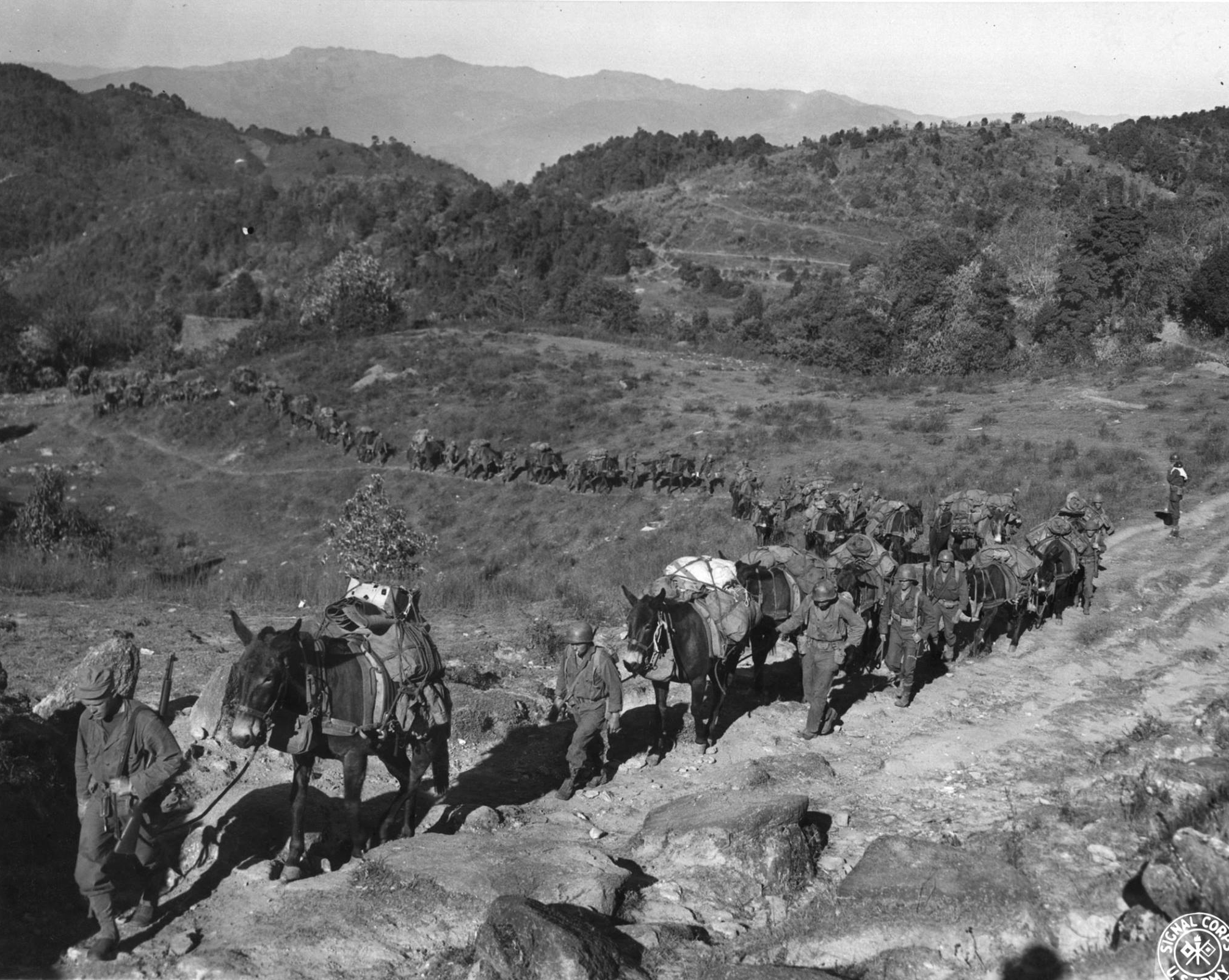

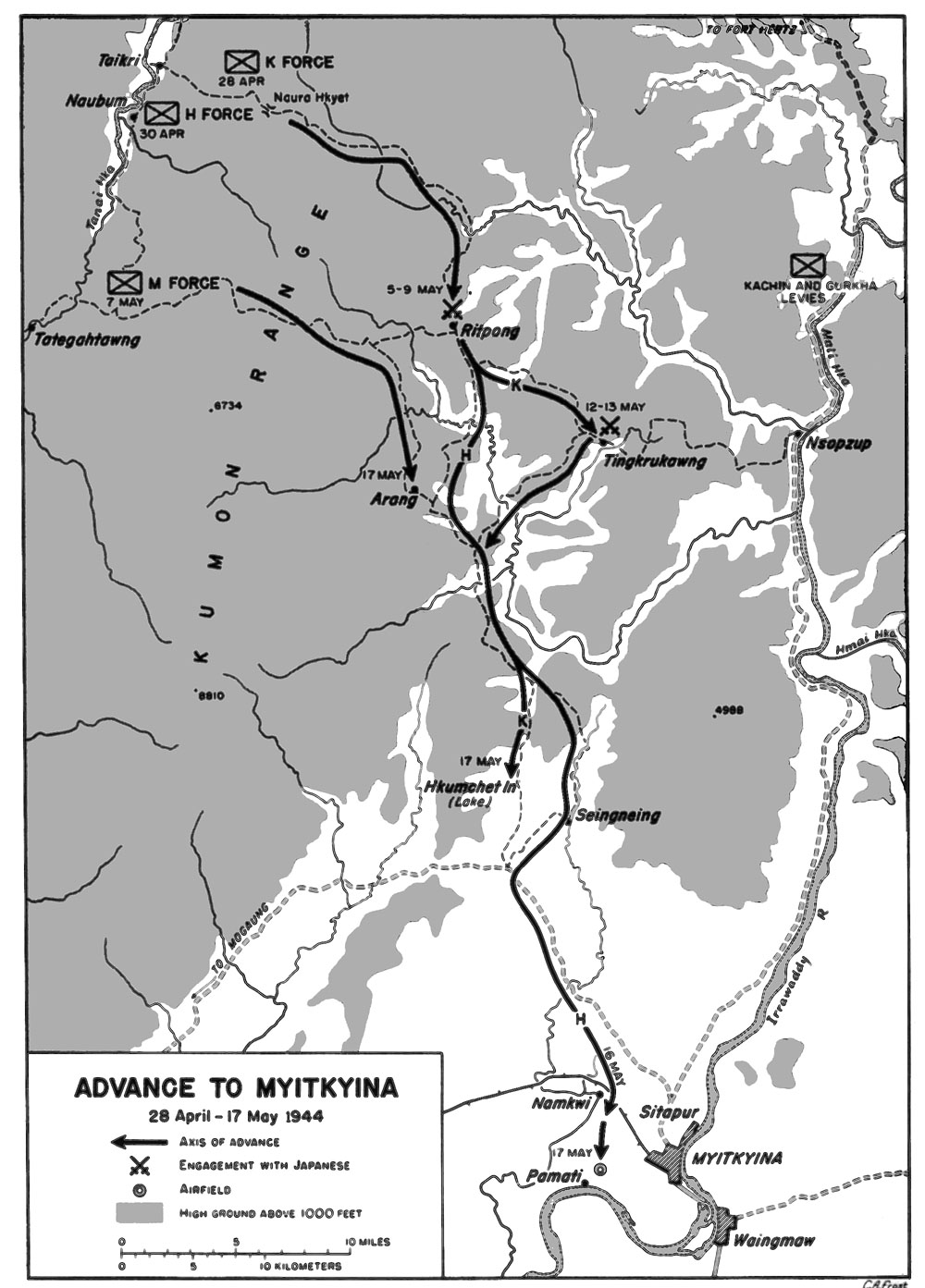

On Mar 3, when Slim had visited Stilwell’s headquarters at the start of the operation to take Maingkwan and Walawbum, Stilwell had told him about his idea for a rapid thrust across the Kumon Range to approach Myitkyina from the north. Whether or not he could actually do it, Stilwell said, depended on how things went and when he captured Shaduzup. Shaduzup was taken on Mar 29. On Apr 3, with his force of more than five divisions left intact, Stilwell told Slim that he expected to be in Myitkyina about May 20. Originally, when Stilwell had taken field command of the Chinese Army in India in December, his vision of how to take Myitkyina had been for the 22nd Division and the 38th Division simply to advance across the Hukawng Valley, push over the Jambu Bum ridge, move down the Mogaung Valley to Mogaung, and then attack northeastward to Myitkyina. The 5307 was to aid this advance by making deep flanking movements that cut Japanese lines of communication and disrupted Japanese defenses. Stilwell also had hopes that, at some point, a Y-Force offensive would facilitate his advance by drawing Japanese forces away from north Burma, However, the slow progress of the Chinese in Dec, Jan, and Feb coupled with the failure of the Y-Force to move-had made it less and less likely that this plan would bring his force to Myitkyina before the rains.

Then, in Feb, Brig J.F. Bowerman, commander of the British Fort Hertz area in northern Burma, had suggested to Stilwell that a little-known pass through the Kumon Range east of Shaduzup could be used for a mobile force like Galahad to attack Myitkyina from the north.

This idea had appealed to Stilwell because it offered the chance to make up for lost time. Not only could he break free from the slow pace of the Chinese movement, but his force could also outflank the Japanese forces defending the Mogaung Valley and achieve surprise at Myitkyina. This was the plan that Stilwell discussed with Slim on Mar 3 and again on Apr 3. This is what Slim knew Stilwell intended to do when Slim told him on Apr 3 to push on for Myitkyina as hard as he could go. By mid-April, Stilwell was confident that a deep strike by a Galahad-led force could reach Myitkyina. Studies of the terrain and trail network indicated that a task force could cross the Kumon Range. The new Chinese divisions, moreover, would soon be available. The airlift of the 50th Division into Maingkwan was almost completed, and the 14th Division was assembling at airfields in Yunnan.

The only major question remaining before initiating the operation, already code-named End Run, was the condition of the 5307 after the battle at Nhpum Ga. To determine the status of the 5307, Stilwell sent his G-3, Col Henry L. Kinnison, to Hsamshingyang shortly after the fighting ended to see firsthand how the men looked. Kinnison told Hunter about Stilwell’s intention to organize a task force to go over the Kumon Range and approach Myitkyina from the north, and the two of them, as Hunter recalls, discussed the condition of the men and animals in detail.