While Galahad was forming in the US and moving across the Pacific, plans were being made by the newly created Southeast Asia Command (SEAC) to implement the decisions of the Trident-Quadrant Conferences. The British established the SEAC to provide stronger direction to the upcoming operations in Burma. Its geographical area of responsibility included Burma, Ceylon, Sumatra, Malaya, but not India or China. Reflecting the preponderance of British forces in the theater, a British officer, VAdm Louis Mountbatten, was named supreme Allied Commander.

While Galahad was forming in the US and moving across the Pacific, plans were being made by the newly created Southeast Asia Command (SEAC) to implement the decisions of the Trident-Quadrant Conferences. The British established the SEAC to provide stronger direction to the upcoming operations in Burma. Its geographical area of responsibility included Burma, Ceylon, Sumatra, Malaya, but not India or China. Reflecting the preponderance of British forces in the theater, a British officer, VAdm Louis Mountbatten, was named supreme Allied Commander.

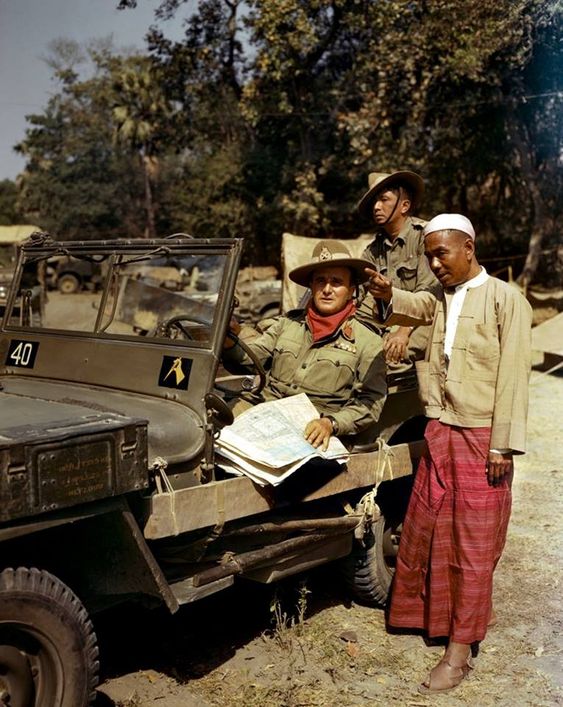

Stilwell was appointed Mountbatten’s acting deputy, but Stilwell’s American operational theater, CBI, was not made subordinate to the SEAC. Also, Stilwell, in his position as Allied CoS to Chiang Kai-Shek, was not subordinate to Mountbatten. Related to the establishment of the SEAC was a crisis in Stilwell’s command relationship to Chiang. When Mountbatten went to Chungking, China’s wartime capital, on Oct 16 to meet Chiang and establish a personal relationship, he was told that Chiang not only did not want Stilwell appointed as Mountbatten’s deputy but wished to have Stilwell recalled to Washington. Mountbatten objected strongly to such a change so close to the upcoming offensive into Burma and precipitated two days of negotiations that ended with Stilwell ostensibly returned to favor. But ritual smiles and professions of a new deeper level of mutual understanding could not reverse the damage already done. Stilwell became more distrustful of Chiang, and a cloud hung over their relationship.

Based on the Quadrant decisions, the Combined CoS gave the Southeast Asia Command two objectives. One was to carry out operations for the capture of upper Burma in order to improve the air route and establish overland communications with China. The other was to continue to build up and increase the air routes and air supplies of China, and the development of air facilities with a view to (a) keeping China in the war, (b) intensifying operations against the Japanese, (c) maintaining increased the US and Chinese air forces in China, and (d) equipping Chinese ground forces.

Based on the Quadrant decisions, the Combined CoS gave the Southeast Asia Command two objectives. One was to carry out operations for the capture of upper Burma in order to improve the air route and establish overland communications with China. The other was to continue to build up and increase the air routes and air supplies of China, and the development of air facilities with a view to (a) keeping China in the war, (b) intensifying operations against the Japanese, (c) maintaining increased the US and Chinese air forces in China, and (d) equipping Chinese ground forces.

To achieve these two objectives, the capture of Myitkyina was deemed essential. Japanese fighter planes flying from their airbase at Myitkyina were able to harass the air route between northeast India (Assam) and China and keep the transports flying farther north over higher mountains in the Himalayas (The Hump). Taking Myitkyina would eliminate this fighter threat. It would also improve greatly the air transport link between India and China, making it possible for transport aircraft to fly a more direct route, at lower altitudes, thereby saving fuel and increasing payloads. Furthermore, Myitkyina was on the existing prewar road network in Burma, so once the Ledo Road was completed through Mogaung to Myitkyina, it would be relatively easy to extend it to the old Burma Road.

The Southeast Asia Command planners developed a multifaceted plan named Champion to retake northern Burma and presented it at the Sextant Conference held in Cairo, Egypt, in Nov 1943. The first phase of the plan called for the advance of the Chinese Army in India (CAI) into northwest Burma to provide a protective screen for the engineers constructing the Ledo Road. This phase was already underway by the time of Sextant. Road building had resumed in earnest in October following the end of the summer monsoon.

In the second phase, two British corps were to invade Burma from the west and southwest in mid-January. In February, three LRPGs were to be landed in central Burma. In addition, a major amphibious landing would be effected. Meanwhile, fifteen Chinese divisions (the Y-Force or Yoke Force that had been equipped and trained by the US) were expected to attack the Japanese westward from the Yunnan Province, in China, into eastern Burma. This Y-Force had also been scheduled to take part in an offensive into Burma in March 1943, but Chiang Kai-Shek had withdrawn his agreement to employ this force and thereby scuttled the offensive.

Now, at the year’s end in Cairo, Chiang was meeting with Roosevelt and Churchill for the first time, and it was assumed that his firm commitment to join in this new operation could be obtained.

Once again, however, the vagaries of coalition warfare intervened. The Sextant Conference ended without a clear commitment by Chiang Kai-Shek for the Chinese participation in the Operation Champion. Then, after Sextant, decisions reached by Churchill and Roosevelt with Stalin at Tehran ensured that Chiang would not become involved.

after Sextant, decisions reached by Churchill and Roosevelt with Stalin at Tehran ensured that Chiang would not become involved.

At Tehran, Roosevelt and Churchill committed themselves to a cross-Channel assault, (Operation Overlord) and a landing in southern France (Operation Anvil/Dragoon) as soon as possible, and Stalin promised to enter the war against Japan after Germany was defeated. This led Churchill to voice strong opposition to the amphibious landing that was part of the Operation Champion, even though Chiang had made it clear that such an operation was a prerequisite for his sending the Y-Force into Burma.

Churchill, at this point, felt that China mattered little in the war against Japan. He believed that Stalin’s promise to join the war against Japan after Germany’s defeat meant that Russian bases would soon be available, and in his opinion, such bases would be better than anything the Chinese could offer. Also, Churchill wanted the amphibious landing craft allocated to Champion shifted to the Mediterranean to be used in the landing in southern France.

On Dec 5, Roosevelt reluctantly agreed to Churchill’s request (overruling the Joint Chiefs of Staff for the only time during the war), and a message was sent to Chiang explaining their decision. Chiang replied that without an amphibious landing to divert Japanese forces, he could not risk sending the Y-Force into Burma.

On Dec 12, Stilwell returned to Chungking from Cairo and tried to change Chiang’s mind about employing the Y-Force. He was unsuccessful. On Dec 18, however, Chiang made a significant concession and gave Stilwell complete authority over the Chinese Army in India. The entry in Stilwell’s personal diary for Dec 19, reveals the excitement and the hope that this move engendered: December 19. First time in history. G-mo  Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek, gave me the full command of the Ledo (X force) troops. Without strings-said there would be no interference and that it was my army. Gave me full power to fire any and all officers. Cautioned me not to sacrifice it to British interests. Otherwise, use it as I saw fit. Madame Chiang, Chiang Kai-Shek’s wife, promised to get this in writing so I could show it to all concerned. It took a long time, but apparently confidence has been established. A month or so ago I was to be fired and now he gives me a blank check. If the bastards will only fight, we can make a dent in the Japs. There is a chance for us to work down to Myitkyina, block off below Mogaung and actually make the junction, even with Yoke-Force sitting on its tukas. This may be wishful thinking in a big way, but it could be.

Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek, gave me the full command of the Ledo (X force) troops. Without strings-said there would be no interference and that it was my army. Gave me full power to fire any and all officers. Cautioned me not to sacrifice it to British interests. Otherwise, use it as I saw fit. Madame Chiang, Chiang Kai-Shek’s wife, promised to get this in writing so I could show it to all concerned. It took a long time, but apparently confidence has been established. A month or so ago I was to be fired and now he gives me a blank check. If the bastards will only fight, we can make a dent in the Japs. There is a chance for us to work down to Myitkyina, block off below Mogaung and actually make the junction, even with Yoke-Force sitting on its tukas. This may be wishful thinking in a big way, but it could be.

In a nutshell, this diary entry captures the nature of Stilwell’s problems. In keeping with the Quadrant-Sextant goal of retaking northern Burma, he was focused on the objectives of capturing Myitkyina and linking up with the Y-Force attacking from the Yunnan Province. But if the Y-Force did not advance, he was not sure if the Ledo Force (the two divisions called the China Army in India, the 22 and 38 Chinese Divisions, or the X-Force) could reach Myitkyina and make the linkup alone. Stilwell acknowledged that all hope of success might be wishful thinking, but he was determined to give his enterprise a try.

A letter written to his wife on the same day further reveals his thoughts: Put down Dec 18, 1943, as the day, when for the first time in history, a foreigner was given command of Chinese troops with full control over all officers and no strings attached – this has been a long uphill fight and when I think of some of our commanders who are handed a ready-made, fully equipped, well-trained army of Americans to work with, it makes me wonder if I’m not working out some of my past sins.

They gave me a shoestring and now we’ve run it up to considerable proportions. The question is, will it snap when we put the weight on it? I’ve had word from Peanut, the Stilwell’s name for Chiang Kai-Shek, that I can get away from this dump tomorrow. That means I’ll spend Christmas with the Confucianists in the jungle – until this mess is cleaned up I wouldn’t want to be doing anything but working at it, and you wouldn’t want me to either, thank God.

Stilwell’s reference to the shoestring that has been run up to considerable proportions refers to the Chinese Army in India, a force that was his own creation. In May 1942, he had looked at the 9000 Chinese soldiers who had retreated from Burma into India and seen the nucleus of a force that could play an important role in a campaign to retake northern Burma.

Overcoming British doubts, resistance from the government of India, and Chiang Kai-Shek’s reluctance, he had obtained agreement to equip and train not only those 9000 troops but 23.000 more soldiers that were to be flown in from China. A former camp for Italian prisoners of war located northwest of Calcutta at Ramgarh was selected as the training site, and on Aug 26, 1942, the Ramgarh Training Center was activated.

Overcoming British doubts, resistance from the government of India, and Chiang Kai-Shek’s reluctance, he had obtained agreement to equip and train not only those 9000 troops but 23.000 more soldiers that were to be flown in from China. A former camp for Italian prisoners of war located northwest of Calcutta at Ramgarh was selected as the training site, and on Aug 26, 1942, the Ramgarh Training Center was activated.

On Oct 20, the first of the Chinese soldiers to be sent from China arrived in India. The first goal was to train two complete divisions, the 22nd Chinese Division and the 38th Chinese Division. Later, the training program was expanded to include another division, the 30th Chinese Division, and the Chinese 1st Provisional Tank Group, commanded by Col Rothwell H. Brown of the US Army.

For Stilwell, building the Chinese Army in India was a way to obtain the military force that he feared the United States would never be able to provide him. He also viewed it as an opportunity to test his deeply held belief that Chinese soldiers, if properly trained, equipped, fed, and led, would be the equal of soldiers anywhere. In an agreement reached on Jul 24, 1942, Chiang Kai-Shek had given Stilwell command of the CAI at Ramgarh and control of its training; the Chinese were to handle administration and discipline. With this much freedom of action, Stilwell initiated an American-style training program with American instructors.

They taught the use of rifles, light and heavy machine guns, 60-MM and 81-MM mortars, rocket launchers, hand grenades, 37-MM antitank guns, and the functional specialties required by modern warfare. Artillery units learned how to use 75-MM pack artillery, 105-MM and 155-MM howitzers, and assault guns. All units received training in jungle warfare. For medical service personnel, special emphasis was given to field sanitation so that the diseases that had taken a heavy toll in Burma in the spring of 1942 could at least be partially prevented.