Under the direction of Torgerson and unit leaders, the two parachute companies in reserve moved forward in a skirmish line and established contact on the flank of their fellows from Able Co. They met only ‘slight resistance’ in the process but soon came under heavy attack as the Japanese renewed their assault on the hill. Edson later thought that this action ‘succeeded in breaking up a threatening hostile envelopment of our position’ and ‘was a decisive factor in our ultimate victory’. The new line of raiders and paratroopers was not very strong, just a small horseshoe bent around the bare slopes of the knoll, with troops from the two battalions still intermingled in many spots. The artillery kept up a steady barrage the most intensive concentration of the campaign according to the division’s final report. And all along the line, Marines threw hand grenade after hand grenade to support the fire of their automatic weapons. Supplies of ammunition dwindled rapidly and moving cases of grenades and belted machine gun rounds to the front line became a key element of the fight.

Under the direction of Torgerson and unit leaders, the two parachute companies in reserve moved forward in a skirmish line and established contact on the flank of their fellows from Able Co. They met only ‘slight resistance’ in the process but soon came under heavy attack as the Japanese renewed their assault on the hill. Edson later thought that this action ‘succeeded in breaking up a threatening hostile envelopment of our position’ and ‘was a decisive factor in our ultimate victory’. The new line of raiders and paratroopers was not very strong, just a small horseshoe bent around the bare slopes of the knoll, with troops from the two battalions still intermingled in many spots. The artillery kept up a steady barrage the most intensive concentration of the campaign according to the division’s final report. And all along the line, Marines threw hand grenade after hand grenade to support the fire of their automatic weapons. Supplies of ammunition dwindled rapidly and moving cases of grenades and belted machine gun rounds to the front line became a key element of the fight.

At 0400, Edson asked the division to commit the reserve battalion to bolster his depleted forces. One company at a time, the men of the 2/5-USMC Regiment, moved along the spine of the ridge and into place beside those who had survived the long night. By dawn, the Japanese had exhausted their reservoir of fighting spirit and Kawaguchi admitted defeat in the face of a tenacious defense backed by superior firepower. The enemy began to break contact and retreat, although a number of small groups and individuals remained scattered through the jungle on the flanks and in the rear of the Marine position. The men of the 2/5-USMC Regiment began the long process of rooting out these snipers, while Edson ordered an air strike to hasten the departure of the main Japanese force. A flight of P-40s answered the call and strafed the enemy infantry still clinging to the exposed forward slopes of Hill 80.

The raiders and the paratroopers walked off the ridge that morning and returned to their previous bivouac in the coconut grove. Although an accurate count of Japanese bodies was impossible, the division estimated there were some 700 dead sprawled around the small battlefield. Of Kawaguchi’s 500 wounded, few would survive the difficult trek back to the coast. The two-day battle on the ridge had cost the 1st Raiders 135 men and the 1st Parachute Battalion 128. Of those totals, 59 were dead or missing, including 15 parachutists killed in action. Many of the wounded parachutists would eventually return to duty, but for the moment the battalion was down to about 100 effective, the equivalent of a severely understrength rifle company. It was no longer a useful tactical entity and had seen its last action on Guadalcanal. Three days later, a convoy brought the 7th Marines to the island and the remaining men of the 1st Parachute Battalion embarked in those ships for a voyage to a welcome period of rest and recuperation in a rear area. The parachute battalion had contributed a great deal to the successful prosecution of the campaign. They had made the first American amphibious assault of the war against a defended beach and fought through intense fire to secure the island. Despite their meager numbers, lack of senior leadership, and minimal firepower, they had stood with the raiders against difficult odds on the ridge. The 1st Marine Division’s final report on Guadalcanal lauded that performance: the actions and conduct of those who participated in the defense of the ridge are deserving of the warmest commendation. The troops engaged were tired, sleepless, and battle-weary at the outset. Throughout the night they held their positions in the face of powerful attacks by overwhelming numbers of the enemy. Driven from one position they reorganized and clung tenaciously to another until daylight found the enemy again in full flight.

Looking back on the campaign after the war, Gen Vandegrift would say: I think the most crucial moment was the Battle of the Ridge.

RECUPERATION AND REEVALUATION

The 1st Parachute Battalion arrived in New Caledonia and went into a ‘dreadful’ transient camp. For the next few weeks, the area headquarters assigned the tired, sick men of the orphaned unit to unload ships and work on construction projects. Luckily, Col Williams returned to duty after recovering from his wound and took immediate steps to rectify the situation. The battalion’s last labor project was building its own permanent quarters, named Camp Kiser after Lt Walter W. Kiser, killed at Gavutu. The site was picturesque; a grassy, undulating plain rising into low hills and overlooking the Tontouta River. Wooden structures housed the parachute loft and mess halls, but for the most part, the officers and men lived and worked in tents. The 24 transport planes of VMJ-152 and VMJ-253 occupied a nearby airfield. The parachutists made a few conditioning hikes while they built their camp and began serious training in November. The first order of business was reintroducing themselves to their primary specialty since none of them had touched a parachute in many months. They practiced packing and jumping and graduated to tactical training emphasizing patrolling and jungle warfare. The 1st Battalion received company on January 11, 1943, when the 2nd Battalion arrived at Tontouta and went into bivouac at Camp Kiser. The West Coast parachute outfit had continued to build itself up while his East Coast counterpart sailed with the 1st Marine Division and fought at Guadalcanal. During the summer of 1942, the 2nd Battalion had found enough aircraft in busy Southern California to make mass jumps with up to 14 planes. (Though ‘mass’ is a relative term here; an entire battalion required about 50 R3D-2s to jump at once).

The 1st Parachute Battalion arrived in New Caledonia and went into a ‘dreadful’ transient camp. For the next few weeks, the area headquarters assigned the tired, sick men of the orphaned unit to unload ships and work on construction projects. Luckily, Col Williams returned to duty after recovering from his wound and took immediate steps to rectify the situation. The battalion’s last labor project was building its own permanent quarters, named Camp Kiser after Lt Walter W. Kiser, killed at Gavutu. The site was picturesque; a grassy, undulating plain rising into low hills and overlooking the Tontouta River. Wooden structures housed the parachute loft and mess halls, but for the most part, the officers and men lived and worked in tents. The 24 transport planes of VMJ-152 and VMJ-253 occupied a nearby airfield. The parachutists made a few conditioning hikes while they built their camp and began serious training in November. The first order of business was reintroducing themselves to their primary specialty since none of them had touched a parachute in many months. They practiced packing and jumping and graduated to tactical training emphasizing patrolling and jungle warfare. The 1st Battalion received company on January 11, 1943, when the 2nd Battalion arrived at Tontouta and went into bivouac at Camp Kiser. The West Coast parachute outfit had continued to build itself up while his East Coast counterpart sailed with the 1st Marine Division and fought at Guadalcanal. During the summer of 1942, the 2nd Battalion had found enough aircraft in busy Southern California to make mass jumps with up to 14 planes. (Though ‘mass’ is a relative term here; an entire battalion required about 50 R3D-2s to jump at once).

The battalion also benefited from its additional time in the States, as it received Johnson rifles and light machine guns in place of the reviled Reisings. However, the manpower pipeline was still slow, as Charlie Co did not come into being until September 3, 1942 (18 months after the first paratroopers reported to San Diego for duty). The battalion sailed from San Diego in October 1942, arrived at Wellington (New Zealand) in November, and departed for New Caledonia on January 6, 1943. As the 2nd Battalion prepared to head overseas, it detached a cadre to form the 3rd Parachute Battalion, which officially came into existence on September 16, 1942. Compared to its older counterparts, the 3rd Battalion grew like a weed and reached full strength by the end of December. The battalion commander, Maj Robert T. Vance, emphasized infantry tactics, demolition work, guerrilla warfare, and physical conditioning in addition to parachuting. At the beginning of 1943, the battalion simulated a parachute assault behind enemy lines in support of a practice amphibious landing by the 21st Marines on San Clemente Island. The fully trained outfit sailed from San Diego in March and joined the 1st and 2nd Battalions at Camp Kiser before the end of the month.

The battalion also benefited from its additional time in the States, as it received Johnson rifles and light machine guns in place of the reviled Reisings. However, the manpower pipeline was still slow, as Charlie Co did not come into being until September 3, 1942 (18 months after the first paratroopers reported to San Diego for duty). The battalion sailed from San Diego in October 1942, arrived at Wellington (New Zealand) in November, and departed for New Caledonia on January 6, 1943. As the 2nd Battalion prepared to head overseas, it detached a cadre to form the 3rd Parachute Battalion, which officially came into existence on September 16, 1942. Compared to its older counterparts, the 3rd Battalion grew like a weed and reached full strength by the end of December. The battalion commander, Maj Robert T. Vance, emphasized infantry tactics, demolition work, guerrilla warfare, and physical conditioning in addition to parachuting. At the beginning of 1943, the battalion simulated a parachute assault behind enemy lines in support of a practice amphibious landing by the 21st Marines on San Clemente Island. The fully trained outfit sailed from San Diego in March and joined the 1st and 2nd Battalions at Camp Kiser before the end of the month.

At the end of 1942, the Marine Corps had transferred the parachute battalions from their respective divisions and made them a Marine Amphibious Corps asset. This recognized their special training and unique mission and theoretically allowed them to withdraw from the battlefield and rebuild while the divisions remained engaged in extended land combat. After the 3rd Battalion arrived in New Caledonia in March 1943, the 1-MAC took the next logical step and created the 1st Parachute Regiment on April 1. This fulfilled Holland Smith’s original call for a regimental-size unit and provided for unified control of the battalions in combat and in training. Col Williams became the first commanding officer of the new organization.

At the end of 1942, the Marine Corps had transferred the parachute battalions from their respective divisions and made them a Marine Amphibious Corps asset. This recognized their special training and unique mission and theoretically allowed them to withdraw from the battlefield and rebuild while the divisions remained engaged in extended land combat. After the 3rd Battalion arrived in New Caledonia in March 1943, the 1-MAC took the next logical step and created the 1st Parachute Regiment on April 1. This fulfilled Holland Smith’s original call for a regimental-size unit and provided for unified control of the battalions in combat and in training. Col Williams became the first commanding officer of the new organization.

Just when things appeared most promising for Marine parachuting, the Corps shifted into reverse gear. Gen Holcomb and planners at Headquarters had not shown much enthusiasm for the program since mid-1940 and apparently began to have strong second thoughts in the fall of 1942. In October, Gen Keller E. Rockey, the director of Plans and Policies at HQMC, had queried the 1-MAC about the ‘use of parachutists’ in its geographic area. There is no record of a reply, but 1-MAC later sent Col Williams in a B-24 bomber to make an aerial reconnaissance of New Georgia in the Central Solomons for a potential airborne operation.

In early 1943, 1-MAC dragged its feet on planning for the Central Solomons mission and the Navy eventually turned to the Army’s XIV Corps headquarters to command the June invasion of New Georgia. In March, the Navy decided that Vandegrift would take over 1-MAC in July, with Thomas as his chief of staff. They had suffered the loss of some of their best men to the parachute and raider programs during the difficult buildup of the 1st Marine Division and both believed that ‘the Marine Corps wasn’t an outfit that needed these specialties’. They made their thoughts on the subject known to Headquarters. The chronic shortage of aircraft also continued to hobble the program. In the summer of 1943, the Corps had just seven transport squadrons, with only one more on the drawing boards. If the entire force had been concentrated in one place, it could only have carried about one and a half battalions. As it was, three squadrons were brand new and still in the States and another one operated out of Hawaii. There were only three in the South Pacific theater. These were fully engaged in logistics operations and were the sole asset available to make critical supply runs on short notice. As an example, the entire transport force in New Caledonia spent the middle of October 1942 ferrying aviation gas to Guadalcanal, 10 drums per plane, in the aftermath of the bombardment of Henderson Field by Japanese battleships. They also evacuated 2879 casualties during the course of that campaign. Senior commands would have been unwilling to divert the planes from such missions for the time required to train the crews and parachutists for a mass jump in an operation. The Army’s transport fleet was equally busy and MacArthur would not assemble enough assets to launch his first parachute assault of the Pacific War until September 1943 (a regimental drop in New Guinea supported by 96 C-47s). The regiment was unable to do any jumping after May 1943 due to the lack of aircraft. The 2nd Battalion’s last jump was a night drop from 15 Army Air Corps C-47s. The planes came over Tontouta off course. Unaware of the problem, the Marines jumped out onto a hilly, wooded area. One paratrooper died and 11 were injured. Thereafter, the paratroopers focused on amphibious operations and ground combat. Col Victor H. Krulak drew rubber boats for his 2nd Battalion and worked on raider tactics.

In early 1943, 1-MAC dragged its feet on planning for the Central Solomons mission and the Navy eventually turned to the Army’s XIV Corps headquarters to command the June invasion of New Georgia. In March, the Navy decided that Vandegrift would take over 1-MAC in July, with Thomas as his chief of staff. They had suffered the loss of some of their best men to the parachute and raider programs during the difficult buildup of the 1st Marine Division and both believed that ‘the Marine Corps wasn’t an outfit that needed these specialties’. They made their thoughts on the subject known to Headquarters. The chronic shortage of aircraft also continued to hobble the program. In the summer of 1943, the Corps had just seven transport squadrons, with only one more on the drawing boards. If the entire force had been concentrated in one place, it could only have carried about one and a half battalions. As it was, three squadrons were brand new and still in the States and another one operated out of Hawaii. There were only three in the South Pacific theater. These were fully engaged in logistics operations and were the sole asset available to make critical supply runs on short notice. As an example, the entire transport force in New Caledonia spent the middle of October 1942 ferrying aviation gas to Guadalcanal, 10 drums per plane, in the aftermath of the bombardment of Henderson Field by Japanese battleships. They also evacuated 2879 casualties during the course of that campaign. Senior commands would have been unwilling to divert the planes from such missions for the time required to train the crews and parachutists for a mass jump in an operation. The Army’s transport fleet was equally busy and MacArthur would not assemble enough assets to launch his first parachute assault of the Pacific War until September 1943 (a regimental drop in New Guinea supported by 96 C-47s). The regiment was unable to do any jumping after May 1943 due to the lack of aircraft. The 2nd Battalion’s last jump was a night drop from 15 Army Air Corps C-47s. The planes came over Tontouta off course. Unaware of the problem, the Marines jumped out onto a hilly, wooded area. One paratrooper died and 11 were injured. Thereafter, the paratroopers focused on amphibious operations and ground combat. Col Victor H. Krulak drew rubber boats for his 2nd Battalion and worked on raider tactics.

In late August, 1-MAC contemplated putting them to work seizing a Japanese seaplane base at Rekat Bay (Santa Isabel), but the enemy evacuated the installation before the intended D-Day. Near the end of April 1943, Rockey suggested to the Commandant that the Corps disband the parachute school at New River and use its personnel to form the fourth and final battalion. He estimated that the production of 30 new jumpers per week at San Diego would be sufficient to maintain field units at full strength. The reduction in school overhead and the training pipeline would relieve some of the pressure on Marine manpower, while the barracks and classroom space at New River would meet the needs of the burgeoning Women’s Reserve program. Gen Harry Schmidt, acting in place of Holcomb, signed off on the recommendations. Baker Co of the 4th Battalion had formed in Southern California on April 2, 1943. Nearly all of the 33 officers and 727 enlisted men of the New River school transferred to Camp Pendleton in early July to flesh out the remainder of the battalion. Transport planes were hard to come by in the States, too, and the outfit never conducted a tactical training jump during its brief existence.

The Allied campaign in the Central Solomons had as its ultimate objective the encirclement and neutralization of the major Japanese air and naval base of Rabaul. As the South Pacific Command contemplated its next step toward that goal, it initially focused on the Shortland Islands, but these were too heavily defended in comparison with the available Allied forces. Planners then turned their attention to Choiseul Island. Once seized, airbases there would allow US air power to neutralize enemy airfields on the northern and southern tips of Bougainville. Gen Douglas MacArthur, the Southwest Pacific commander, wanted to short-circuit the process and move directly to Bougainville, which would allow American fighter planes to effectively support bomber attacks on Rabaul.

Adm William F. Halsey’s South Pacific command had too few transports and Marines to make a direct assault on the strongly garrisoned airfields on the northern and southern tips of Bougainville, so he decided to seize the Empress Augusta Bay region midway up the western side of the island and build his own airbases. Defenses there were negligible and Bougainville‘s difficult terrain would prevent any rapid reaction from enemy ground forces located elsewhere on the island.

Adm William F. Halsey’s South Pacific command had too few transports and Marines to make a direct assault on the strongly garrisoned airfields on the northern and southern tips of Bougainville, so he decided to seize the Empress Augusta Bay region midway up the western side of the island and build his own airbases. Defenses there were negligible and Bougainville‘s difficult terrain would prevent any rapid reaction from enemy ground forces located elsewhere on the island.

D-Day for the Empress Augusta Bay operation was November 1, 1943. Two regiments of the 3rd Marine Division and two marine raider battalions (organized regiment as the 2nd Raider Regiment), and the 3rd Defense Battalion formed the assault echelon for the landing. The division’s third regiment, the Army’s 37th Infantry Division, and assorted other units would arrive later to reinforce the perimeter while construction troops built the new airfields. The 1-MAC staff slated the 1st Parachute Regiment as the reserve force. The 2nd Parachute Battalion sailed to Guadalcanal in early September and then moved forward to a staging area at Vella Lavella on October 1.

D-Day for the Empress Augusta Bay operation was November 1, 1943. Two regiments of the 3rd Marine Division and two marine raider battalions (organized regiment as the 2nd Raider Regiment), and the 3rd Defense Battalion formed the assault echelon for the landing. The division’s third regiment, the Army’s 37th Infantry Division, and assorted other units would arrive later to reinforce the perimeter while construction troops built the new airfields. The 1-MAC staff slated the 1st Parachute Regiment as the reserve force. The 2nd Parachute Battalion sailed to Guadalcanal in early September and then moved forward to a staging area at Vella Lavella on October 1.

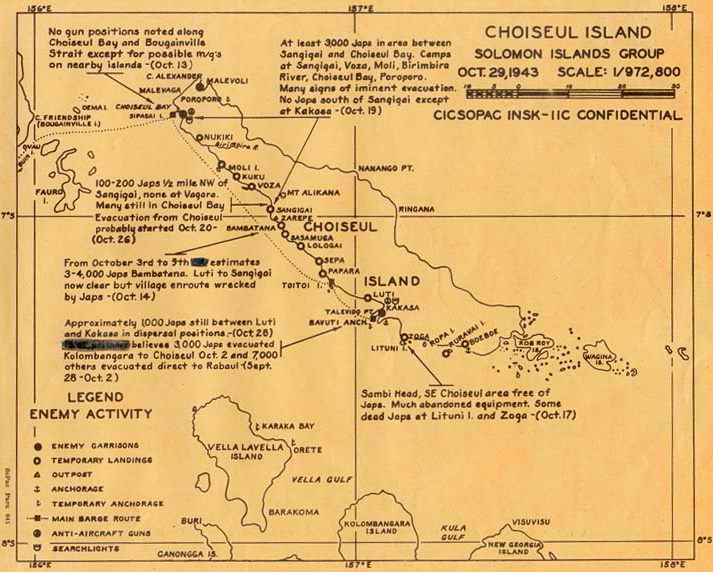

New Zealand and US forces already had secured part of that island, but the Japanese still were contesting control of the air overhead and small bands of soldiers were roaming the jungle. Enemy planes struck the parachute battalion’s small convoy of three APDs and an LST as it unloaded and put two bombs into the tank landing ship just as it was preparing to touch the beach. It sank in shallow water, which allowed most of the troops to make it ashore. But 14 paratroopers and the battalion lost most of its supplies and unit equipment. Once established in camp, the parachutists conducted patrols to search for Japanese stragglers on the island. The rest of the regiment arrived in Vella Lavella during the latter part of October. As the final planning for Bougainville progressed, the 1-MAC staff grew concerned that preliminary operations might make it obvious to the Japanese that an invasion was in the offing. To address that problem, in mid-October, Maj James C. Murray, staff secretary, advanced the idea that a raid on Choiseul, might make the enemy think that it was the next objective. Even if that did not dissuade them about Bougainville, it might cause them to suspect that a US landing on Bougainville would come on the east coast, since Choiseul would be a move in that direction. On October 20, Vandegrift brought Col Krulak, the 2nd Battalion commander, to Guadalcanal for a conference with the 1-MAC staffers, who outlined the scheme. The corps issued final orders on October 22, for the 2nd Parachute Battalion to begin the raid six days later. Intelligence indicated there were up to 4000 Japanese on the island, most of them dispersed in small camps along the coast awaiting transportation for a withdrawal to Bougainville. Their supply situation supposedly was poor, although planners believed they still had most of their weapons, including mortars and light artillery.

New Zealand and US forces already had secured part of that island, but the Japanese still were contesting control of the air overhead and small bands of soldiers were roaming the jungle. Enemy planes struck the parachute battalion’s small convoy of three APDs and an LST as it unloaded and put two bombs into the tank landing ship just as it was preparing to touch the beach. It sank in shallow water, which allowed most of the troops to make it ashore. But 14 paratroopers and the battalion lost most of its supplies and unit equipment. Once established in camp, the parachutists conducted patrols to search for Japanese stragglers on the island. The rest of the regiment arrived in Vella Lavella during the latter part of October. As the final planning for Bougainville progressed, the 1-MAC staff grew concerned that preliminary operations might make it obvious to the Japanese that an invasion was in the offing. To address that problem, in mid-October, Maj James C. Murray, staff secretary, advanced the idea that a raid on Choiseul, might make the enemy think that it was the next objective. Even if that did not dissuade them about Bougainville, it might cause them to suspect that a US landing on Bougainville would come on the east coast, since Choiseul would be a move in that direction. On October 20, Vandegrift brought Col Krulak, the 2nd Battalion commander, to Guadalcanal for a conference with the 1-MAC staffers, who outlined the scheme. The corps issued final orders on October 22, for the 2nd Parachute Battalion to begin the raid six days later. Intelligence indicated there were up to 4000 Japanese on the island, most of them dispersed in small camps along the coast awaiting transportation for a withdrawal to Bougainville. Their supply situation supposedly was poor, although planners believed they still had most of their weapons, including mortars and light artillery.

The 2nd Parachute Battalion’s mission was to land at an undefended area near Voza, conduct raids along the northwestern coast, select a site for a possible PT [patrol torpedo] boat base, and withdraw after 12 days if the Navy decided it did not want to establish a PT boat facility. The paratroopers were to give the enemy the impression that they were a large force trying to seize Choiseul. To beef up the battalion’s firepower, 1-MAC attached a platoon of machine guns from the regimental weapons company and an experimental rocket platoon. (The latter unit – a lieutenant and eight men – had 40 of these fin-stabilized, 65-pound weapons. They were not very accurate, but their 1000-meter range and large warhead gave the lightly armed battalion a hefty punch. A detachment of four landing craft would remain with the force and give it some mobility. A Navy PBY also landed at Choiseul and brought out an Australian detachment of coast watchers, Carden W. Seton, who would accompany the raid force and ensure it received the full support of local natives. Altogether the reinforced battalion numbered about 700 men. Krulak planned a night landing at 0100 on October 28. His order emphasized the nature of the operation: The ‘basic principle is a strike and move; avoid decisive engagement with superior forces’. Early in the evening of October 27, four APDs and the destroyer USS Conway (DD-507) hove to off Vella Lavella. The 2nd Battalion, which had half its supplies already preloaded in landing craft, completed debarkation in less than an hour. The small convoy had a short but eventful trip to Choiseul, as an unidentified aircraft dropped bombs close aboard one of the APDs. The ships arrived early off Voza and the small Marine force was completely ashore by 0100.