By September 6, Japanese naval activity and native scouting reports indicated that the enemy was concentrating fresh troops near the village of Tasimboko, located on the coast several miles east of the Marine lines. Edson and Col Gerald C. Thomas, the division operations officer, hatched a plan to raid this eastern terminus of the Tokyo Express on September 8. Intelligence initially placed two or three hundred Japanese at Tasimboko, with their defenses located west of the village and facing toward Henderson Field. Edson planned to land to the east of the village and attack them from the rear. The available shipping consisted of two transport destroyers (APDs) and two small, converted tuna boats, so the raider commander divided his force into two waves. The raider rifle companies would embark on the evening of September 7 and land just prior to dawn, then the tiny fleet would shuttle back to the perimeter to pick up the weapons company and the paratroopers. Since the APDs were needed for other missions, the Marine force would have to complete its work and reembark the same day, the Navy had already lost 3 of the original 6 APDs in Guadalcanal. On the evening of September 7, native scouts brought news that the enemy force at Tasimboko had swelled to several thousand. Division planners discounted these reports, believing that they were greatly exaggerated or referred to remnants of previously defeated formations. When the raiders landed at 0520 a day later, they immediately realized that the natives had provided accurate information. Not far from the beach, Marines discovered endless rows of neatly placed life preservers, a large number of foxholes, and several unattended 37-MM antitank guns. Luckily for Edson’s outfit, Gen Kiyotake Kawaguchi and his brigade of more than 3000 men already had departed into the interior. Only a rearguard of 300 soldiers remained behind to secure the Japanese base at Tasimboko, but even that small force was nearly as large as the first wave of raiders.

Dog Co of the raiders (little more than a platoon in strength) remained at the landing beach as rear security while the other companies moved west toward Tasimboko. The raiders soon ran into stubborn resistance, with the Japanese firing artillery over open sights directly at the advancing Marines. Edson sent one company-wide to the left to flank the defenders. As the action developed, the APDs Manley and McKean returned to Kukum Beach at 0755 and the Parachute Battalion (less Charlie Co) debarked within 25 minutes. The 208 paratroopers joined Dog Co ashore by 1130 and went into defensive positions adjacent to them. Edson, fearing that he might be moving into a Japanese trap, already had radioed division twice and asked for reinforcements, including another landing to the west of Tasimboko in what was now the enemy rear. In reply, the division ordered the raiders and the paratroopers to withdraw. Edson persisted, however, and Japanese resistance melted away about noon. The raider assault echelon entered the village and discovered a stockpile of food, ammunition, and weapons ranging up to 75-MM artillery pieces. The raider and parachute rear guard closed up on the main force and the Marines set about destroying the enemy supply base. Three hours later the combined unit began to reembark and all were back in the division perimeter by nightfall. The raid was a minor tactical victory with a major operational impact on the Guadalcanal Campaign. At a cost of two killed and six wounded, the Marines had killed 27 Japanese. The enemy suffered more grievously in terms of lost firepower, logistics, and communication. Intelligence gathered at the scene also revealed some details about the coming Japanese offensive. These latter facts would allow the 1st Marine Division to fight off one of the most serious challenges to its tenuous hold on Henderson Field.

THE BLOODY BATTLE OF AND AROUND EDSON’S RIDGE

On September 9, Edson met with division planners to discuss the results of the raid. Intelligence officers translating captured documents indicated that up to 3000 Japanese were cutting their way through the jungle southwest of Tasimboko. Edson was convinced that they planned to attack the unguarded southern portion of the perimeter. From an aerial photograph, he picked out a grass-covered ridge that pointed like a knife at the airfield. He based his hunch on his experience with the Japanese and in jungle operations in Nicaragua. Col Thomas agreed. Vandegrift, just in the process of moving his command post into that area, was reluctant to accept a conclusion that would force him to move yet again. After much discussion, he allowed Thomas to shift the bivouac of the raiders and parachutists to the ridge to get them out of the pattern of bombs falling around the airfield. The combined force moved to the new location on September 10 and quickly discovered that it was not the rest area they had hoped to enjoy. Orders came down from Edson to dig in and enemy aircraft bombed the ridge on September 11 and 12, inflicting several casualties. Native scouts reported the progress of the Japanese column and Marine patrols confirmed the presence of strong enemy forces to the southeast of the perimeter.

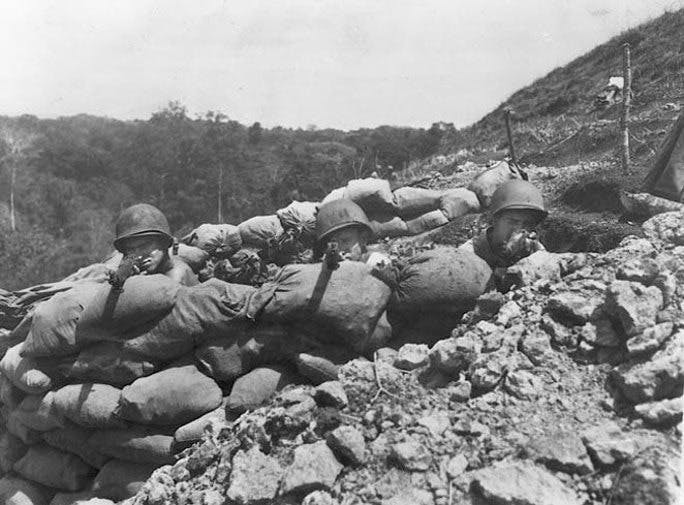

The raiders and the paratroopers found the process of constructing defensive positions toughgoing. There were very little barbed wire and no sandbags or heavy tools. Men digging in on the ridge itself found coral just below the shallow surface soil. The units disposed in the flanking jungle were hampered by the thick growth, which reduced fields of fire to nothing. Both units were smaller than ever, as tropical illnesses, poor diet, and lack of sleep combined to swell the number of men in the field hospital. Those still listed as effective often were just barely so. Edson faced a tough situation as he contemplated how to defend the ridge area. Several hundred yards to the right of his coral hogback was the Lunga River; beyond it, elements of the 1st Pioneer and 1st Amphibious Tractor Battalions had strong points. More than a mile to his left was the tail end of the 1st Marine Regiment’s positions along the Tenaru River. With the exception of the kunai grass-covered slopes of the ridge, everything else was a dense jungle. His small force, about the size of a single infantry battalion but lacking all the heavy weapons, could not possibly establish a classic linear defense. Edson placed the paratroopers on the east side of the ridge with Baker Co holding a line running from the slope of Hill 80 into the jungle. The other two companies echeloned to the rear to hold the left flank. Baker Co occupied the right slope of Hill 80 and anchored their right on a lagoon; Charlie Co placed platoon strong points between the lagoon and the river, and the remaining raiders were in reserve near Hill 120. Thomas moved the 2/5-USMC Regiment, into position between the ridge and the airfield and reoriented some of his artillery to fire to the south. Artillery forward observers joined Edson’s command post on the front slope of Hill 120 and registered the guns.

On the Jap’s side, Kawaguchi’s Brigade faced its own troubles as it fought through the jungle and over the numerous slimy ridges. The rough terrain forced the Japanese to leave behind their artillery and most of their supplies. Their commander also detailed one of his four battalions to make a diversionary attack along the Tenaru, which left him with just 2500 men for the main assault. To make matters worse, the Japanese had underestimated the jungle and fallen behind schedule. As the sunset on September 12, Kawaguchi realized that only one battalion was in its assembly area and none of his units had been able to reconnoiter their routes of attack. The Japanese general tried to delay the jump-off scheduled for 2200, but he could not contact his battalions. Without guides and running late, the attack blundered forward in the darkness and soon degenerated into confusion. At the appointed hour, a Japanese float plane dropped green flares over the Marine positions. A cruiser and three destroyers began shelling the ridge area and kept up the bombardment for 20 minutes, though few rounds landed on their intended target; many sailed over the ridge into the jungle beyond. Japanese infantry followed up with their own flares and began to launch their assault. The enemy’s confusion may have benefited the parachute battalion since all the action occurred on the raider side of the position. The enemy never struck the ridge proper but did dislodge Charlie Co’s raiders, who fell back and eventually regrouped near Hill 120. At daylight, the Japanese broke off the attack and tried to reorganize for another attempt the next night. In the morning, Edson ordered a counterattack by the raiders of Dog Co and the paratroopers of Able Co to recapture Charlie Co’s position.

The far more numerous Japanese stopped them cold with machine gunfire. Since he could not eject the Japanese from a portion of his old front, the raider commander decided to withdraw the entire line to the reserve position. In the late afternoon, Baker Cos of both, raiders and paratroopers, pulled back and anchored themselves on the ridge between Hills 80 and 120. The division provided an engineer company, which Edson inserted on the right of the ridge. Able Co of the raiders covered the remaining ground to the Lunga. Charlie Co paratroopers occupied a draw just to the left rear of their own Baker Co, while Able Co held another draw on the east side of Hill 120. The raiders of Charlie and Dog Cos assumed a new reserve position on the west slope of the ridge, just behind Hill 120. Edson’s forward command post was just in front of the top of Hill 120.

Kawaguchi renewed his attack right after darkness fell on September 13. His first blow struck the right flank of the raiders’ Baker Co and drove more than a platoon of those Marines out of their positions. Most linked up with Charlie Co in their rear, while the remainder of Baker Co clung to its position in the center of the ridge. The Japanese did not exploit the gap, except to send some infiltrators into the rear of the raider and parachute line. They apparently cut some of the phone lines running from Edson’s command post to his companies, though he was able to warn the parachutists of the threat in their rear.

Kawaguchi renewed his attack right after darkness fell on September 13. His first blow struck the right flank of the raiders’ Baker Co and drove more than a platoon of those Marines out of their positions. Most linked up with Charlie Co in their rear, while the remainder of Baker Co clung to its position in the center of the ridge. The Japanese did not exploit the gap, except to send some infiltrators into the rear of the raider and parachute line. They apparently cut some of the phone lines running from Edson’s command post to his companies, though he was able to warn the parachutists of the threat in their rear.

By 2100, the Japanese obviously were massing around the southern nose of the ridge, lapping around the flanks of the two Baker Cos, and making their presence known with firecrackers, flares, a hellish bedlam of howls, and rhythmic chanting designed to strike fear into the heart of their enemy and draw return fire for the purpose of pinpointing automatic weapons. Edson responded with a fierce artillery barrage and orders to Charlie Co raiders and Able Co paratroopers to form a reserve line around the front and sides of Hill 120. As Japanese mortar and machine gun fire swept the ridge, Capt William J. McKennan and 1/Sgt Marion LeNoir gathered their paratroopers and led them into position around the knoll.

The Japanese assault waves finally surged forward around 2200. The attack, focused on the open ground of the ridge, immediately unhinged the remainder of the Marine center. Capt Justin G. Duryea, commanding the Baker Co paratroopers, ordered his men to withdraw as Marine artillery shells fell ever closer to the front lines and Japanese infantry swarmed around his left flank. He also believed that the remainder of the Baker Co raiders already was falling back on his right. To add to the confusion, Marines thought they heard shouts of gas attack as smoke rose up from the lower reaches of the ridge. Duryea’s small force ended up next to Charlie Co in the draw on the east slope, where he reported to Torgerson, now the battalion executive officer. The units were clustered in low-lying ground and had no contact on their flanks. Torgerson ordered both companies to withdraw to the rear of Hill 120, where he hoped to reorganize them in the lee of the reserve line and the masking terrain. Given the collapse of the front line, it was a reasonable course of action. The withdrawal of the parachutists left the rump of the raiders, perhaps 60 men, alone in the center of the front line.

The Japanese assault waves finally surged forward around 2200. The attack, focused on the open ground of the ridge, immediately unhinged the remainder of the Marine center. Capt Justin G. Duryea, commanding the Baker Co paratroopers, ordered his men to withdraw as Marine artillery shells fell ever closer to the front lines and Japanese infantry swarmed around his left flank. He also believed that the remainder of the Baker Co raiders already was falling back on his right. To add to the confusion, Marines thought they heard shouts of gas attack as smoke rose up from the lower reaches of the ridge. Duryea’s small force ended up next to Charlie Co in the draw on the east slope, where he reported to Torgerson, now the battalion executive officer. The units were clustered in low-lying ground and had no contact on their flanks. Torgerson ordered both companies to withdraw to the rear of Hill 120, where he hoped to reorganize them in the lee of the reserve line and the masking terrain. Given the collapse of the front line, it was a reasonable course of action. The withdrawal of the parachutists left the rump of the raiders, perhaps 60 men, alone in the center of the front line.

Edson arranged for covering fire from the artillery and the troops around Hill 120, then ordered Baker Co back to the knoll. There they joined the reserve line, which was now the new front line. This series of rearward movements threatened to degenerate into a rout. Night movements under fire are always confusing and commanders no longer had positive control of coherent units. There was no neat line of fighting holes to occupy, no time to hold muster and sort out raiders from paratroopers and get squads, platoons, and companies back together again. A few men began to filter to the rear of the hill, while others lay prone waiting for direction. Edson, with his command post now in the middle of the front line, took immediate action. The raider commander ordered Torgerson to lead his Companies, Baker and Charlie, from the rear of the hill and lengthen the line running from the left of Able Co’s position. Edson then made it known that this would be the final stand, that no one was authorized to retreat another step. Maj Kenneth D. Bailey, commander of the raiders from Charlie Co, played a major role in revitalizing the defenders. He moved along the line of mingled raiders and paratroopers, encouraging everyone and breathing new life into those on the verge of giving up.