The Jedburghs were three-man teams parachuted into occupied France after D-Day to develop liaison with the Resistance. They were truly inter-allied, French (103), Belgian (5), Dutch (5), British (90) and American (83). Each of the 93 teams included a Frenchman, with the remaining two members divided more or less equally between British and American officers.

Jedburg Missions, (Officially) The mission of the Jedburgh teams was to supplement existing OSS/SOE ‘circuits,’ to help organize and arm the resistance, arrange supply drops, procure intelligence, provide liaison between the Allies and the Resistance, and to take part in sabotage operations.

Project Jedburgh was a joint Allied program, with the OSS Special Operations (OSS) branch, the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), and the French Bureau Central de Renseignements et d’Action (BCRA) involved.

Eighty-three American, 90 British, 103 French, 5 Belgian, and 5 Dutch personnel were extensively trained in paramilitary techniques for Jedburgh missions. Ninety-three Jedburgh teams parachuted into France and eight went into The Netherlands.

A model team consisted of one French, one British, and one American serviceman. Every team had at least one officer and a radioman, but team sizes vary from two to four men.

The purpose of the Jedburgh and the Jedburgh Operations is to coordinate the French resistance actions with the allied strategic and tactical plans of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force in order to slow down German troops’ movement in France. These operations were done by airdropping equipment and personnel belonging to the Special Operations Executive (SOE), the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and the Free France Central Bureau of Intelligence and Action (BCRA) to local French resistance networks.

The British, experts in commando operations, initiated the project in the fall of 1943 and began the selection of hand-picked cadres from the Special Air Service (SAS). With an excellent physical condition, these volunteers must be determined and accept to endure multiple tests while perfecting their technical skills. Col Wilkinson of the SOE gave the code name Jedburgh to these small teams trained to work alone and deep into enemy territory. The term Jedburgh comes from the name of a town located on the Scottish border, near which many exercises were organized like Spartan, the first training setting the bases of the general concept of these operations.

In the summer of 1944, Allied special operations teams known as Jedburghs parachuted into occupied Europe to cooperate with resistance groups behind German lines and to aid in the advance of Allied ground forces. Each of the 19 Jedburgh teams consisted of three special trained volunteers. Clandestine operations of the kind that the Jeds conducted often have been recounted in memoirs and novels, but only a portion of the actual operational records have been declassified. The Jeds, as they called themselves, were but one group charged with clandestine work. Individual agents, inter-Allied missions, Special Air Service (SAS) troops and other such organization will only be included in this study when they specifically influenced Jeds operations.

This study examines the operations of the 11 Jeds teams dropped into northern France during the summer of 1944, with particular emphasis on the degree to which they assisted in the advance of Gen Omar N. Bradley’s 12th Army Group from Normandy to the German border. The treatment of these Jeds teams will be arranged chronologically, by date of insertion. The area of operations covered by these teams reached from the Belgian border in the north, south to Nancy. Jed operations south of Nancy lie beyond the scope of this study. The operational records of these 11 northern teams form the core of the documentation for this study, although a good deal of the story told here has been gleaned from other sources, memories, and interviews with Jeds veterans.

This study examines the operations of the 11 Jeds teams dropped into northern France during the summer of 1944, with particular emphasis on the degree to which they assisted in the advance of Gen Omar N. Bradley’s 12th Army Group from Normandy to the German border. The treatment of these Jeds teams will be arranged chronologically, by date of insertion. The area of operations covered by these teams reached from the Belgian border in the north, south to Nancy. Jed operations south of Nancy lie beyond the scope of this study. The operational records of these 11 northern teams form the core of the documentation for this study, although a good deal of the story told here has been gleaned from other sources, memories, and interviews with Jeds veterans.

Regrettably, the records of the Special Forces Headquarters, the organization with Gen Dwight D. Eisenhower’s SHAEF that provided operational command and control for Jed teams, remain classified and, therefore, were not available for use in this study. I have resolved to follow MRD Foot’s examples and capitalized the names of intelligence circuits to assist the reader amid the sea of names and code names used to protect these operations.

Regrettably, the records of the Special Forces Headquarters, the organization with Gen Dwight D. Eisenhower’s SHAEF that provided operational command and control for Jed teams, remain classified and, therefore, were not available for use in this study. I have resolved to follow MRD Foot’s examples and capitalized the names of intelligence circuits to assist the reader amid the sea of names and code names used to protect these operations.

The name of each individual in the text is the individual’s real name (as well as that can be determined), Nom de Guerre of each French Jeds will be mention in the appropriate footnote. I have adopted the word Axis as a generic term for the German-dominated security forces. In some instances, these rear-area defense forces were not German, but Vichy security forces, such as the Milice.

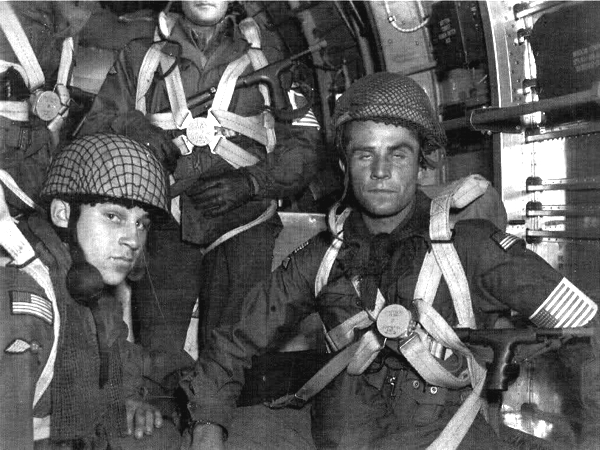

The sun was setting on July 7, 1944, at Harrington Air Base some fifty miles north of London. Capt Bill Dreux, a 31-year-old lawyer from New Orleans, like his two partners was weighed down by a Colt M-1911-A1 cal .45 pistol, a cal. 30 carbine, ammo, binoculars, money belt, escape kit, flashlight, tobacco, map case and could barely move.

Overall this equipment each man wore a camouflaged British paratrooper body-length smock (Denison). Dreux felt wrapped like a mummy and had trouble getting out of the station wagon. Finally, after the driver-assisted each out of the vehicle, the three tightly wrapped men waddled in short, jerky steps toward a black-painted B-24 Liberator.

The absurdity of the situation was not lost on the bomber’s US Army Corps crew, who succumbed to laughter. After a last cigarette, Bill Dreux, his partners, and the crew scaled the B-24 and took off for Brittany. Dreux and his two colleagues were Jeds. Jeds were volunteers specially trained to conduct guerrilla warfare in conjunction with the French Resistance in support of the Allied invasion of France.

Bill Dreux and his two partners survived their mission. Their story has already been told, however, and with some skill in one of the few Jed memoirs. This paper will examine the role of the 11 Jed teams parachuted into northern France in the summer of 1944 whose story has not been told. These 11 teams, like Dreux’s, has worked with mostly French teenagers and the few Frenchmen not drafted into Germany labor or prisoners of war in Germany.

Bill Dreux and his two partners survived their mission. Their story has already been told, however, and with some skill in one of the few Jed memoirs. This paper will examine the role of the 11 Jed teams parachuted into northern France in the summer of 1944 whose story has not been told. These 11 teams, like Dreux’s, has worked with mostly French teenagers and the few Frenchmen not drafted into Germany labor or prisoners of war in Germany.

Many Jed teams had difficulty radioing London, and some that did contact London doubted that their reports were acted upon. After the Jeds operations in France concluded, the teams’ after-action reports reflected a sense, not of failure, but rather of frustration. The teams felt they could have been used more effectively. The major reason for this frustration was a professional officer Corps, unfamiliar with the capabilities of unconventional warfare and the multiplicity of secret organizations (several of them new) competing for recognition, personal, funds and missions.

Following the fall of France, in July 1940, the Chamberlain cabinet, in one of its last acts, created the Special Operations Executive, (SOE). Independent of other British Intelligence Service, its charter was suitably unique, two foster sabotage activity in axis-occupied countries.

Two offices in the War Office and one in the Foreign Office had been studying the subject since 1938, and they combined to form SOE. Although SOE ran intelligence circuits, it was independent of the Secret or Special Intelligence Service, (SIS), which today is known as MI6.

In a similar fashion, the Special Air Service Regiment remained independent of the SOE and the SIS. David Stirling who created the SAS in 1941, summarized his organization’s purpose as follows: firstly, raids in-depth behind the enemy lines, attacking Headquarters nerve centers, landing grounds, supply lines and so on; and, secondly, the mounting of sustained strategic offensive activity from secret bases within hostile territory and, if the opportunity existed, recruiting, training, arming and coordinating local guerrilla elements.

In a similar fashion, the Special Air Service Regiment remained independent of the SOE and the SIS. David Stirling who created the SAS in 1941, summarized his organization’s purpose as follows: firstly, raids in-depth behind the enemy lines, attacking Headquarters nerve centers, landing grounds, supply lines and so on; and, secondly, the mounting of sustained strategic offensive activity from secret bases within hostile territory and, if the opportunity existed, recruiting, training, arming and coordinating local guerrilla elements.

The United States approached World War II without a strategic intelligence organization. It first created the Committee of Information, a conspicuous failure that soon became the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Its director, William ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan, allowed it to duplicate the functions and methods of the British Intelligence Organizations, to which it was closely tied. But whereas the British effort was marked by independent competing organs, Donovan attempted to unify the many facets of the secret world in his neophyte OSS.

The United States approached World War II without a strategic intelligence organization. It first created the Committee of Information, a conspicuous failure that soon became the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Its director, William ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan, allowed it to duplicate the functions and methods of the British Intelligence Organizations, to which it was closely tied. But whereas the British effort was marked by independent competing organs, Donovan attempted to unify the many facets of the secret world in his neophyte OSS.

Following September 1942, the OSS special operations branch joined the SOE London Group to create a combined office known as SOE/SO on Baker Street in London. S0E’s first director, Dr. Hugh Dalton, explained his organization’s purpose as follows: we have got to organize movements in enemy-occupied territory comparable to the Sinn Fein in Ireland, to the Chinese Guerillas now operating against Japan, to the Spanish Irregulars who played a notable part in Wellington’s campaign or – one might as well admit it – to the organizations which the nazis themselves have developed so remarkably in almost every country in the world. This ‘democratic international’ must use many different methods, including industrial and military sabotage, labor agitation and strikes, continuous propaganda, terrorist acts against traitors and German leaders, boycotts and riots.

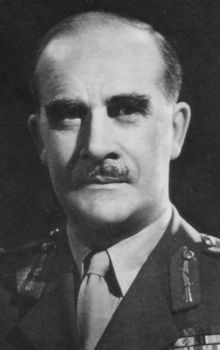

One of the most important personalities in the SOE was Sir Colin McVean Gubbins, who eventually became its executive director. Born in Japan in 1896, Gubbins was a slight Scot who had served in the artillery on the Western Front in World War One, in Ireland during the Troubles, and in northern Russia during the Russian Civil War. In 1939, in the War Office’s small unconventional war section, he wrote two short pamphlets: The Art of Guerilla Warfare and Partisan Leaders’ Handbook. He created the Independent Companies (later renamed commandos) and successfully led several of them in Norway in 1940.

One of the most important personalities in the SOE was Sir Colin McVean Gubbins, who eventually became its executive director. Born in Japan in 1896, Gubbins was a slight Scot who had served in the artillery on the Western Front in World War One, in Ireland during the Troubles, and in northern Russia during the Russian Civil War. In 1939, in the War Office’s small unconventional war section, he wrote two short pamphlets: The Art of Guerilla Warfare and Partisan Leaders’ Handbook. He created the Independent Companies (later renamed commandos) and successfully led several of them in Norway in 1940.

May 1942 found Sir Colin McVean Gubbins a brigadier general and, with the title of a military deputy, at the head of the SOE. In May 1942, the SOE entered into talks involving its support of a future Allied invasion of northwestern Europe.

The British Chief of Staff foresaw the SOE activity occurring in two phases. In the first phase (cooperation during the initial invasion) the SOE would organize and arm resistance forces and take action against the enemy’s rail and signal communications, air personnel, etc. During the second phase, after the landing, the SOE would provide guides for British conventional units, guards for important locations, labor parties, and organized raiding parties capable of penetrating behind German lines.

Brig Gubbins and the SOE developed the Jedburgh concept from these discussions with one paper, drafted by Peter Wilkinson, summarizing its activities as follows: as and when the invasion commences, the SOE will drop additional small teams of French-speaking personnel carrying arms for some forty men each. The role of these teams will be to make contact with local authorities or existing SOE organizations, to distribute the arms, to start off the action of the patriots, and, most particularly, to arrange by W/T (Wireless Telegraphy) communication the dropping points and reception committees for further arms and equipment on the normal SOE system. Each Team will consist of one British Officer, one W/T operator with a radio set and possibly one guide.

Brig Gubbins and the SOE developed the Jedburgh concept from these discussions with one paper, drafted by Peter Wilkinson, summarizing its activities as follows: as and when the invasion commences, the SOE will drop additional small teams of French-speaking personnel carrying arms for some forty men each. The role of these teams will be to make contact with local authorities or existing SOE organizations, to distribute the arms, to start off the action of the patriots, and, most particularly, to arrange by W/T (Wireless Telegraphy) communication the dropping points and reception committees for further arms and equipment on the normal SOE system. Each Team will consist of one British Officer, one W/T operator with a radio set and possibly one guide.

On July 6, Gubbins (recently promoted to major general) briefly explained the project to the head of the SOE security section, requesting a code name for teams to raise and arm the civilian population to carry out guerrilla activities against the enemy’s lines of communication.

The following day, the security section issued the project the code name Jedburgh, after a small town on the Scots-English border. The Jedburgh project evolved along with the changing Allied invasion plans of the Continent.

The following day, the security section issued the project the code name Jedburgh, after a small town on the Scots-English border. The Jedburgh project evolved along with the changing Allied invasion plans of the Continent.

Later in the month, the SOE resolved that seventy Jedburgh teams would be required, with the British and Americans each providing thirty-five. In August 1942, the British Chiefs of Staff informed the SOE that there was no longer a requirement for Jedburgh teams to provide guides and labor or raiding parties, effectively eliminating phase two of the original proposal.

On December 24, 1942, a meeting at General Headquarters Home Forces, determined that the Jedburghs would all be uniformed soldiers and that one of the two officers in each team should be of the nationality of the country to which the team would deploy. This signified that the project would require Belgian, Dutch, and French soldiers.

Furthermore, Jedburgh teams would be dropped to secure areas, where SOE agents would receive them. Each team would be given one or more military tasks to perform in their area. In addition, since it would take at least seventy-two hours to deploy a team and have them operational, Jedburgh teams would not be used to assist the tactical plans of conventional ground forces. Finally, the SOE would provide twelve Jedburgh teams to further examine the concept’s possibilities and limitations during Exercise Spartan from March 3-11 1943.

Exercise Spartan simulated an Allied breakout from the initial invasion lodgment area. SOE’s Jedburgh teams attempted to assist the British Second Army advance, with the 8th Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers in the role of local resistance groups. The SOE also used this opportunity to test the insertion of individual agents behind enemy lines and the role of the SOE staff officers at the army and corps headquarters. Each of these parties communicated via an SOE radio base in Scotland.

Exercise Spartan simulated an Allied breakout from the initial invasion lodgment area. SOE’s Jedburgh teams attempted to assist the British Second Army advance, with the 8th Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers in the role of local resistance groups. The SOE also used this opportunity to test the insertion of individual agents behind enemy lines and the role of the SOE staff officers at the army and corps headquarters. Each of these parties communicated via an SOE radio base in Scotland.

Following the exercise, the SOE concluded that the Jedburgh teams should be inserted at least forty miles behind enemy lines to conduct small-scale guerrilla operations against enemy lines of communication. The exercise also demonstrated that each army and army group headquarters required an SOE liaison and signal detachment. The SOE also concluded that it should maintain a small detachment with the Supreme Headquarters.

SOE and OSS, after compiling the Spartan lessons learned, both began the process of moving similar position papers through the British and American hierarchies, seeking approval, support, and personnel. On July 19, 1943, Gen Frederick R. Morgan, Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander, recommended that the SOE proposals be approved. To his understanding, the SOE would provide small staffs and signal detachments to each army and army group headquarters (and the Supreme Allied Commander’s headquarters) for controlling resistance groups.

SOE and OSS, after compiling the Spartan lessons learned, both began the process of moving similar position papers through the British and American hierarchies, seeking approval, support, and personnel. On July 19, 1943, Gen Frederick R. Morgan, Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander, recommended that the SOE proposals be approved. To his understanding, the SOE would provide small staffs and signal detachments to each army and army group headquarters (and the Supreme Allied Commander’s headquarters) for controlling resistance groups.

Jedburgh teams would constitute a strategic reserve in England until D Day to provide, if necessary, suitable leadership and equipment for those resistance groups found to be in need of them.