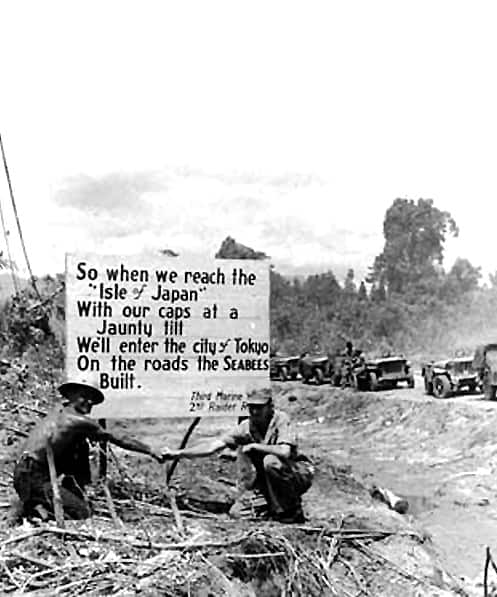

On November 1, 1943, the 3rd Marines and the 9th Marines, assisted by the 2nd Raider Battalion, seized a swath of Bougainville‘s coast from Cape Torokina to the northwest. At the same time, elements of the 3rd Raider Battalion assaulted Puruata Island just off the cape. The single Japanese company and one 75-MM gun defending the area gave a good account of themselves until overwhelmed by the invasion force. Over the next several days the Marines advanced inland to extend their perimeter.  There were occasional engagements with small enemy patrols, but the greatest resistance during this period came from the terrain, which consisted largely of swampland and dense jungle beginning just behind the beach. The thing most Marines remembered about Bougainville was the deep, sucking mud that seemed to cover everything not already underwater.

There were occasional engagements with small enemy patrols, but the greatest resistance during this period came from the terrain, which consisted largely of swampland and dense jungle beginning just behind the beach. The thing most Marines remembered about Bougainville was the deep, sucking mud that seemed to cover everything not already underwater.

Japanese resistance stiffened as they moved troops to the area on foot and by barge. The Marines fought several tough battles in mid-November and suffered significant casualties trying to move forward through the thick vegetation, which concealed Japanese defensive positions until the Marines were just a few feet away. Heavy rains and the ever-present mud made logistics a nightmare and quickly exhausted the troops. Nevertheless, the perimeter continued to expand as 1-MAC sought an area large enough to protect the future airfields from enemy interference.

Japanese resistance stiffened as they moved troops to the area on foot and by barge. The Marines fought several tough battles in mid-November and suffered significant casualties trying to move forward through the thick vegetation, which concealed Japanese defensive positions until the Marines were just a few feet away. Heavy rains and the ever-present mud made logistics a nightmare and quickly exhausted the troops. Nevertheless, the perimeter continued to expand as 1-MAC sought an area large enough to protect the future airfields from enemy interference.

By November 20, 1-MAC had all of the 3rd Marine Division and the 37th Infantry Division, plus the 2nd Raider Regiment, on the island. In accordance with the original plan, corps headquarters arranged for the parachute regiment to come forward in echelon from Vella Lavella and assume its role as the reserve force.

By November 20, 1-MAC had all of the 3rd Marine Division and the 37th Infantry Division, plus the 2nd Raider Regiment, on the island. In accordance with the original plan, corps headquarters arranged for the parachute regiment to come forward in echelon from Vella Lavella and assume its role as the reserve force.

The 1st Parachute Battalion embarked on board ships on November 22 and arrived at Bougainville the next day, where it joined the raider regiment in reserve. The corps planners wanted to make aggressive use of the reserve force. In addition to assigning it the normal roles of reinforcing or counterattacking, 1-MAC ordered its reserve to be prepared: ‘to engage in land or water-borne raider type operations’.

The 1st Parachute Battalion embarked on board ships on November 22 and arrived at Bougainville the next day, where it joined the raider regiment in reserve. The corps planners wanted to make aggressive use of the reserve force. In addition to assigning it the normal roles of reinforcing or counterattacking, 1-MAC ordered its reserve to be prepared: ‘to engage in land or water-borne raider type operations’.

By November 26, the corps had established a defensible beachhead, and enemy activity was at a low ebb. However, the Japanese 23rd Infantry Regiment occupied high ground to the northeast of the US perimeter and remained a threat. Enemy medium artillery also periodically shelled rear areas. To prevent the Japanese from gathering strength with impunity, 1-MAC decided to establish a force in the enemy rear from whence it could: ‘conduct raids along the coast and inland to the main east-west trail; destroy Japs installations, supplies, with particular attention to disrupting Jap communications and artillery’. The plan called for Maj Richard Fagan’s 1st Parachute Battalion, Mike Co of the raiders, and artillery forward observers to land 10 miles to the east, near Koiari prior to dark on November 28. The raiders would secure the patrol base while the parachutists conducted offensive operations. They would remain there until the corps ordered them to withdraw.

A Japanese air attack and problems with the boat pool delayed the operation for 24 hours. Just after midnight on November 28, the 739 men of the reinforced battalion embarked on landing crafts near Cape Torokina and headed down the coast.

A Japanese air attack and problems with the boat pool delayed the operation for 24 hours. Just after midnight on November 28, the 739 men of the reinforced battalion embarked on landing crafts near Cape Torokina and headed down the coast.

The main body of the parachute battalion went ashore at their assigned objective, but Mike Co and the parachute headquarters company landed nearly 1000 yards farther to the east. Much to the surprise of the first paratroopers coming off the boats, a Japanese officer walked onto the beach and attempted to engage them in conversation. That bizarre incident made some sense when the Marines discovered that they had landed in the midst of a large enemy supply dump.

The main body of the parachute battalion went ashore at their assigned objective, but Mike Co and the parachute headquarters company landed nearly 1000 yards farther to the east. Much to the surprise of the first paratroopers coming off the boats, a Japanese officer walked onto the beach and attempted to engage them in conversation. That bizarre incident made some sense when the Marines discovered that they had landed in the midst of a large enemy supply dump.

The Japanese leader must have thought that these were his own craft delivering or picking up supplies. In any case, the equally surprised enemy put up little opposition to the Marine incursion. Maj Fagan, located with the main body, was concerned about the separation of his unit and felt that the Japanese force in the vicinity of the dump was probably much bigger than his own. Given those factors, he quickly established a tight perimeter defense about 350 yards in width and just 180 yards inland. By daylight, the Japanese had recovered from their shock and begun to respond aggressively to the threat in their rear area. They brought to bear the continuous fire from 90-MM mortars, knee-mortars, machine guns, and rifles; the volume of fire increased as the day wore on.

The Japanese leader must have thought that these were his own craft delivering or picking up supplies. In any case, the equally surprised enemy put up little opposition to the Marine incursion. Maj Fagan, located with the main body, was concerned about the separation of his unit and felt that the Japanese force in the vicinity of the dump was probably much bigger than his own. Given those factors, he quickly established a tight perimeter defense about 350 yards in width and just 180 yards inland. By daylight, the Japanese had recovered from their shock and begun to respond aggressively to the threat in their rear area. They brought to bear the continuous fire from 90-MM mortars, knee-mortars, machine guns, and rifles; the volume of fire increased as the day wore on.

Periodically infantry rushed the Marine lines. The picture improved somewhat by 0930 when the body of raiders and headquarters personnel moved down the beach and fought their way into the battalion perimeter. Something to note also is that the battalion’s radio set malfunctioned about this time, and Fagan could not receive messages from 1-MAC. For the moment he could still send messages out but was unsure if the corps headquarters heard them. Fortunately, the artillery spotters could talk to the batteries, though, and they fed a steady diet of 155-MM shells to the Japanese. Unknown to Fagan, the raider company had its own radio and maintained independent contact with the corps. These communication snafus would lead to great confusion. By late morning, 1-MAC already was thinking in terms of pulling out the beleaguered force. At 1128, it arranged to boat of the 3rd Marine Division half-tracks (mounting 75-MM guns) to assist in covering a withdrawal. Staffers also called in planes to provide close air support. Around noon, Fagan sent a message requesting evacuation and the corps decided to abort the mission. It radioed the battalion at 1318 with information concerning the planned withdrawal, but the paratroopers did not get the word. As a consequence, Fagan sent more messages asking for boats and a resupply of ammunition, which was running low.

Periodically infantry rushed the Marine lines. The picture improved somewhat by 0930 when the body of raiders and headquarters personnel moved down the beach and fought their way into the battalion perimeter. Something to note also is that the battalion’s radio set malfunctioned about this time, and Fagan could not receive messages from 1-MAC. For the moment he could still send messages out but was unsure if the corps headquarters heard them. Fortunately, the artillery spotters could talk to the batteries, though, and they fed a steady diet of 155-MM shells to the Japanese. Unknown to Fagan, the raider company had its own radio and maintained independent contact with the corps. These communication snafus would lead to great confusion. By late morning, 1-MAC already was thinking in terms of pulling out the beleaguered force. At 1128, it arranged to boat of the 3rd Marine Division half-tracks (mounting 75-MM guns) to assist in covering a withdrawal. Staffers also called in planes to provide close air support. Around noon, Fagan sent a message requesting evacuation and the corps decided to abort the mission. It radioed the battalion at 1318 with information concerning the planned withdrawal, but the paratroopers did not get the word. As a consequence, Fagan sent more messages asking for boats and a resupply of ammunition, which was running low.

For some reason, neither Fagan nor the corps headquarters used the artillery net for messages other than calls for fire support. While sending other traffic would have been a violation of standard procedures, it certainly was justified under the circumstances. After the operation was over, Fagan would express dismay that Mike Co radio operators, without his knowledge or approval, had sent their own pleas for boats and ammunition throughout the afternoon. At 1600, the landing craft arrived off the beach and made a run in to pick up the raid force. The Japanese focused their mortar fire on the boats and the sailors backed off. They tried again almost immediately but again drew back due to the intense bombardment from the beach. Things looked bleak as the onset of night reduced visibility to zero in the dense jungle and increased the likelihood of a strong enemy counterattack. Ammunition stocks were dwindling rapidly and weapons failed due to heavy firing and the accumulation of gritty sand. Marines resorted to employing Japanese weapons, including a small field piece.

Three destroyers, the USS Fullam (DD-474), the USS Lansdowne (DD-486) and the USS Lardner (DD-487) accompanied by two LCI gunboats came on the scene after 1800 and turned the tide. The heavy fires at a short range of the Lansdowne and the LCIs soon silenced most of the Japanese mortars and boats were able to reach the shore unmolested about 1920. American artillery also continued to rain down around the perimeter. The parachutists and raiders exhibited a cool discipline, slowly collapsing their perimeter into the beach and conducting an orderly backload. After a thorough search to ensure that no one remained behind, the final few Marines stepped onto the last wave of landing craft and pulled out to sea at 2100. The raid might be counted as a failure since it did not go according to plan, but it did achieve some positive things. The day of fighting in the midst of the enemy supply dump destroyed considerable stocks of ammunition, food, and medical supplies. Rough estimates placed Japanese casualties at nearly 300 dead and wounded, though there was no way to confirm whether this figure was high or low. Undoubtedly the aggressive operation behind the lines caused the enemy to worry that the Americans might repeat the tactic elsewhere with better luck.

Three destroyers, the USS Fullam (DD-474), the USS Lansdowne (DD-486) and the USS Lardner (DD-487) accompanied by two LCI gunboats came on the scene after 1800 and turned the tide. The heavy fires at a short range of the Lansdowne and the LCIs soon silenced most of the Japanese mortars and boats were able to reach the shore unmolested about 1920. American artillery also continued to rain down around the perimeter. The parachutists and raiders exhibited a cool discipline, slowly collapsing their perimeter into the beach and conducting an orderly backload. After a thorough search to ensure that no one remained behind, the final few Marines stepped onto the last wave of landing craft and pulled out to sea at 2100. The raid might be counted as a failure since it did not go according to plan, but it did achieve some positive things. The day of fighting in the midst of the enemy supply dump destroyed considerable stocks of ammunition, food, and medical supplies. Rough estimates placed Japanese casualties at nearly 300 dead and wounded, though there was no way to confirm whether this figure was high or low. Undoubtedly the aggressive operation behind the lines caused the enemy to worry that the Americans might repeat the tactic elsewhere with better luck.

On December 5, the corps attached the parachute regiment (less the 1st and 2nd Battalions) to the 3rd Marines Division, which ordered this fresh force to occupy and defend Hill 1000, while other elements of the division out posted other high ground nearby. To accomplish the mission, Col Williams decided to turn his rump regiment into two battalions by creating a provisional force consisting of the weapons company, headquarters personnel, and the 3rd Battalion’s Item Co. The paratroopers moved out on foot from their bivouac at 1130 with three days of rations and a unit of fire in their packs. By 1800 they were in a perimeter defense around the peak of Hill 1000, 3rd Battalion (less Item Co) on the south and the provisional unit to the north. Supply proved to be the first difficulty, as ‘steep slopes, overgrown trails, and deep mud’ hampered the work of carrying parties. The Division eventually had to resort to airdrops to overcome the problem. While some paratroopers labored to bring up food and ammunition, others patrolled the vicinity. Beginning on December 6, the outpost line began to turn into a linear defense as the division fed more units forward. The small parachute regiment had a hard time trying to cover its 3000 yards of assigned frontage on top of the sprawling, ravine-pocked, jungle-covered hill mass. On December 7, a 3rd Battalion patrol discovered abandoned defensive positions on an eastern spur of Hill 1000. The unit brought back documents showing that a reinforced enemy company had set up a strong point on what would become known as Hellzapoppin Ridge. The battalion commander, Maj Vance, ordered two platoons of King Co to move forward to straighten the line. With no map and only vague directions as a guide, the unit could not find its objective in the dense jungle and remained out of touch until the next day.

On December 5, the corps attached the parachute regiment (less the 1st and 2nd Battalions) to the 3rd Marines Division, which ordered this fresh force to occupy and defend Hill 1000, while other elements of the division out posted other high ground nearby. To accomplish the mission, Col Williams decided to turn his rump regiment into two battalions by creating a provisional force consisting of the weapons company, headquarters personnel, and the 3rd Battalion’s Item Co. The paratroopers moved out on foot from their bivouac at 1130 with three days of rations and a unit of fire in their packs. By 1800 they were in a perimeter defense around the peak of Hill 1000, 3rd Battalion (less Item Co) on the south and the provisional unit to the north. Supply proved to be the first difficulty, as ‘steep slopes, overgrown trails, and deep mud’ hampered the work of carrying parties. The Division eventually had to resort to airdrops to overcome the problem. While some paratroopers labored to bring up food and ammunition, others patrolled the vicinity. Beginning on December 6, the outpost line began to turn into a linear defense as the division fed more units forward. The small parachute regiment had a hard time trying to cover its 3000 yards of assigned frontage on top of the sprawling, ravine-pocked, jungle-covered hill mass. On December 7, a 3rd Battalion patrol discovered abandoned defensive positions on an eastern spur of Hill 1000. The unit brought back documents showing that a reinforced enemy company had set up a strong point on what would become known as Hellzapoppin Ridge. The battalion commander, Maj Vance, ordered two platoons of King Co to move forward to straighten the line. With no map and only vague directions as a guide, the unit could not find its objective in the dense jungle and remained out of touch until the next day.

That night a small Japanese patrol probed the lines of the regiment and the enemy re-occupied the position on the east spur. On the morning of December 8, a patrol from the provisional battalion investigated the spur and a Japanese platoon ambushed it. The paratroopers returned to friendly lines with one man missing. They reorganized and departed an hour later to search for him and tangled with the enemy in the same spot. This time they suffered eight wounded in a 20-minute firefight and withdrew. Twice during the day, the regiment received artillery and mortar fire, which is believed to be friendly in origin. The rounds knocked out the regimental command post’s telephone communications and caused five serious casualties in King Co. In light of the increasing enemy activity, Col Williams decided to straighten out his lines and establish physical contact between the flanks of the battalions. This required the right flank of Item Co and the left flank of King Co to advance.

That night a small Japanese patrol probed the lines of the regiment and the enemy re-occupied the position on the east spur. On the morning of December 8, a patrol from the provisional battalion investigated the spur and a Japanese platoon ambushed it. The paratroopers returned to friendly lines with one man missing. They reorganized and departed an hour later to search for him and tangled with the enemy in the same spot. This time they suffered eight wounded in a 20-minute firefight and withdrew. Twice during the day, the regiment received artillery and mortar fire, which is believed to be friendly in origin. The rounds knocked out the regimental command post’s telephone communications and caused five serious casualties in King Co. In light of the increasing enemy activity, Col Williams decided to straighten out his lines and establish physical contact between the flanks of the battalions. This required the right flank of Item Co and the left flank of King Co to advance.

On the morning of December 9, Maj Vance personally led a patrol to reconnoiter the new position. Eight Japanese manning three machine guns ambushed that force and it withdrew, leaving behind one man. At 1415, the left half of King Co attacked. Within 20 minutes, a strong Japanese rifle and machine-gun fire brought it to a halt. Although after-action reports from higher echelons later indicated only that Item Co did not move forward, those Marines fought hard that day and suffered casualties attempting to advance. Among others, the executive officer, Lt Milt Cunha, was killed in action and Sgt I. J. Fansler Jr had his rifle shot out of his hands.

On the morning of December 9, Maj Vance personally led a patrol to reconnoiter the new position. Eight Japanese manning three machine guns ambushed that force and it withdrew, leaving behind one man. At 1415, the left half of King Co attacked. Within 20 minutes, a strong Japanese rifle and machine-gun fire brought it to a halt. Although after-action reports from higher echelons later indicated only that Item Co did not move forward, those Marines fought hard that day and suffered casualties attempting to advance. Among others, the executive officer, Lt Milt Cunha, was killed in action and Sgt I. J. Fansler Jr had his rifle shot out of his hands.

The inability of Item Co to make progress enlarged the dangerous gap in the center of the regiment’s line. Vance ordered two demolition squads to refuse King’s left flank and Williams sent a platoon of headquarters personnel from the provisional battalion to fill in the remainder of the hole. Snipers infiltrated the Marine line and the regimental commander turned most of his command post group into a reserve force to backstop the rifle companies. The paratroopers called in artillery to King Co’s front and the Japanese fire finally began to slacken after 1615. The fighting was intense and King Co initially reported casualties of 36 wounded and 12 killed. That figure later proved too high, though exact losses in the attack were hard to ascertain since the paratroopers had 18 men missing and took casualties in other actions that day.

The inability of Item Co to make progress enlarged the dangerous gap in the center of the regiment’s line. Vance ordered two demolition squads to refuse King’s left flank and Williams sent a platoon of headquarters personnel from the provisional battalion to fill in the remainder of the hole. Snipers infiltrated the Marine line and the regimental commander turned most of his command post group into a reserve force to backstop the rifle companies. The paratroopers called in artillery to King Co’s front and the Japanese fire finally began to slacken after 1615. The fighting was intense and King Co initially reported casualties of 36 wounded and 12 killed. That figure later proved too high, though exact losses in the attack were hard to ascertain since the paratroopers had 18 men missing and took casualties in other actions that day.

Maj Vance suffered a gunshot wound in the foot and turned over the battalion to Torgerson. The executive officer of the 21st Marines was in the area, apparently reconnoitering prior to his regiment taking over that portion of the front the next day. He responded to a request for assistance and had his Charlie Co haul ammunition up to the paratroopers. When those Marines completed that task, he offered to have them bolster the parachute line and Williams accepted. For the rest of the night, the parachute regiment fired artillery missions at 15-minute intervals against likely enemy positions. The Japs responded with small arms fire. Division shifted the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, to a reserve position behind Hill 1000 and placed the parachute regiment under the tactical control of the 9th Marines, scheduled to occupy the line on their left the next day.

Maj Vance suffered a gunshot wound in the foot and turned over the battalion to Torgerson. The executive officer of the 21st Marines was in the area, apparently reconnoitering prior to his regiment taking over that portion of the front the next day. He responded to a request for assistance and had his Charlie Co haul ammunition up to the paratroopers. When those Marines completed that task, he offered to have them bolster the parachute line and Williams accepted. For the rest of the night, the parachute regiment fired artillery missions at 15-minute intervals against likely enemy positions. The Japs responded with small arms fire. Division shifted the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, to a reserve position behind Hill 1000 and placed the parachute regiment under the tactical control of the 9th Marines, scheduled to occupy the line on their left the next day.