Baker Co landed four minutes after H-Hour against stiff opposition, as did Charlie Co seven minutes later. The latter unit’s commander Capt Richard J. Huerth, took a bullet in the head just as he rose from his boat and he fell back into it dead. Capt Emerson E. Mason, the battalion intelligence officer, also received a fatal wound as he reached the beach. When Charlie Co’s two platoons came ashore, they took up positions facing Tanambogo to return enfilading fire from that direction, while Baker Co began a movement to the left around the hill. That masked them from Tanambogo and allowed them to make some progress. The nature of the enemy action defenders shooting from concealed underground positions surprised the parachutists. Several Marines became casualties when they investigated quiet cave openings, only to be met by bursts of fire. The battalion communications officer died in this manner. Many other parachutists withheld their fire because they saw no targets. Marines tossed grenades into caves and dugouts, but oftentimes soon found themselves being fired on from these ‘silenced’ positions. (Later investigation revealed that baffles built inside the entrances protected the occupants or that connecting trenches and tunnels allowed new defenders to occupy the defensive works). Twenty minutes into the battle, Maj Williams began leading men up Hill 148 and took a bullet in his side that put him out of action. The enemy fire drove off attempts to pull him to safety and his executive officer, Maj Charles A. Miller, took control of the operation. Miller established the command post and aid station in a partially demolished building near the dock area. Around 1400, Miller called for an airstrike against Tanambogo and about half an hour later he radioed for reinforcements.

Baker Co landed four minutes after H-Hour against stiff opposition, as did Charlie Co seven minutes later. The latter unit’s commander Capt Richard J. Huerth, took a bullet in the head just as he rose from his boat and he fell back into it dead. Capt Emerson E. Mason, the battalion intelligence officer, also received a fatal wound as he reached the beach. When Charlie Co’s two platoons came ashore, they took up positions facing Tanambogo to return enfilading fire from that direction, while Baker Co began a movement to the left around the hill. That masked them from Tanambogo and allowed them to make some progress. The nature of the enemy action defenders shooting from concealed underground positions surprised the parachutists. Several Marines became casualties when they investigated quiet cave openings, only to be met by bursts of fire. The battalion communications officer died in this manner. Many other parachutists withheld their fire because they saw no targets. Marines tossed grenades into caves and dugouts, but oftentimes soon found themselves being fired on from these ‘silenced’ positions. (Later investigation revealed that baffles built inside the entrances protected the occupants or that connecting trenches and tunnels allowed new defenders to occupy the defensive works). Twenty minutes into the battle, Maj Williams began leading men up Hill 148 and took a bullet in his side that put him out of action. The enemy fire drove off attempts to pull him to safety and his executive officer, Maj Charles A. Miller, took control of the operation. Miller established the command post and aid station in a partially demolished building near the dock area. Around 1400, Miller called for an airstrike against Tanambogo and about half an hour later he radioed for reinforcements.

While the paratroopers awaited this assistance, Baker Co and a few men from Able Co continued to attack Hill 148 from its eastern flank. Individuals and small groups worked from dugout to dugout under rifle and machine gun fire from the enemy. Learning from initial experience, Marines began to tie demolition charges of TNT to longboards and stuff them into the entrances. That prevented the enemy from throwing back the explosives and it permanently put the positions out of action. Capt Harry L. Torgerson and Cpl Johnnie Blackan distinguished themselves in this effort. Other men, such as Sgt Max Koplow and Cpl Ralph W. Fordyce, took a more direct approach and entered the bunkers with submachine guns blazing. Platoon Sgt Harry M. Tully used his marksmanship skill and Johnson rifle to pick off a number of Japanese snipers.

The paratroopers got their 60-MM mortars into action too and used them against Japanese positions on the upper slopes of Hill 148. By 1430, the eastern half of the island was secure, but enemy fire from Tanambogo kept the parachutists from overrunning the western side of the hill. In the course of the afternoon, the Navy responded to Miller’s call for support. Dive bombers worked over Tanambogo, then two destroyers closed on the island and thoroughly shelled it. In the midst of this action, one pilot mistakenly dropped his ordnance on b>Gavutu‘s hilltop and inflicted several casualties on Baker Co. By 1800, the battalion succeeded in raising the US flag at the summit of Hill 148 and physically occupying the remainder of Gavutu. With the suppression of fire from Tanambogo and the cover of night, the parachutists collected their casualties, including Maj Williams, and began evacuating the wounded to the transports. Ground reinforcements arrived more slowly than fire support. Baker 1/2-USMC Regiment reported to Miller on Gavutu at 1800. He ordered them to make an amphibious landing on Tanambogo and arranged for preparatory fire by a destroyer. The paratroopers also would support the move with their fire and Charlie Co would attack across the causeway after the landing. Miller, perhaps buoyed by the late afternoon decrease in enemy fire from Tanambogo, was certain that the fresh force would carry the day. For his part, Baker Co’s commander left the meeting under the impression that there were only a few snipers left on the island.

The attack ran into trouble from the beginning and the Marine force ended up withdrawing under heavy fire. During the night, the paratroopers dealt with Japanese emerging from dugouts or swimming ashore from Tanambogo or Florida. Heavy rain helped conceal these attempts at infiltration, but the enemy accomplished little. At 2200, Gen Rupertus requested additional forces to seize Tanambogo and the 3/2-USMC Regiment went ashore on Gavutu late in the morning on August 8. They took over many of the positions facing Tanambogo and in the afternoon launched an amphibious attack of one company supported by three tanks. Another platoon followed up the landing by attacking across the causeway. Bitter fighting ensued and the 3rd Battalion did not completely secure Tanambogo until August 9. This outfit suffered additional casualties on August 8 when yet another Navy dive bomber mistook Gavutu for Tanambogo and struck Hill 148.

In the first combat operation of an American parachute unit, the battalion had suffered severe losses: 28 killed and about 50 wounded, nearly all of the latter requiring evacuation. The dead included four officers and 11 NCOs. The casualty rate of just over 20 percent was by far the highest of any unit in the fighting to secure the initial lodgment in the Guadalcanal area. The Raiders were next in line with roughly 10 percent. The Japanese force defending Gavutu-Tanambog was nearly wiped out, with only a handful surrendering or escaping to Florida Island. Despite the heavy odds the paratroopers had faced, they had proved more than equal to the faith placed in their capabilities and had distinguished themselves in a very tough fight. In addition to raw courage, they had displayed the initiative and resourcefulness required to deal with a determined and cunning enemy.

On the night of August 8, a Japanese surface force arrived from Rabaul and surprised the Allied naval forces guarding the transports. In a brief engagement, the enemy sank four cruisers and a destroyer, damaged other ships, and killed 1200 sailors, all at minimal cost to themselves. The American naval commander had little choice the next morning but to order the early withdrawal of his force. Most of the transports would depart that afternoon with their cargo holds half full, leaving the Marines short of food, ammunition, and equipment. The paratroopers suffered an additional loss that would make life even more miserable for them. They had landed on August 7 with just their weapons, ammunition, and a two-day supply of C and D rations. They had placed their extra clothing, mess gear, and other essential field items into individual rolls and loaded them on a landing craft for movement to the beach after they secured the islands. As the paratroopers fought onshore, Navy personnel decided they needed to clear out the boat, so they uncomprehendingly tossed all the gear into the sea. The battalion ended its brief association with Gavutu on the afternoon of August 9 and shifted to a bivouac site on Tulagi.

RAID IN TASIMBOKO

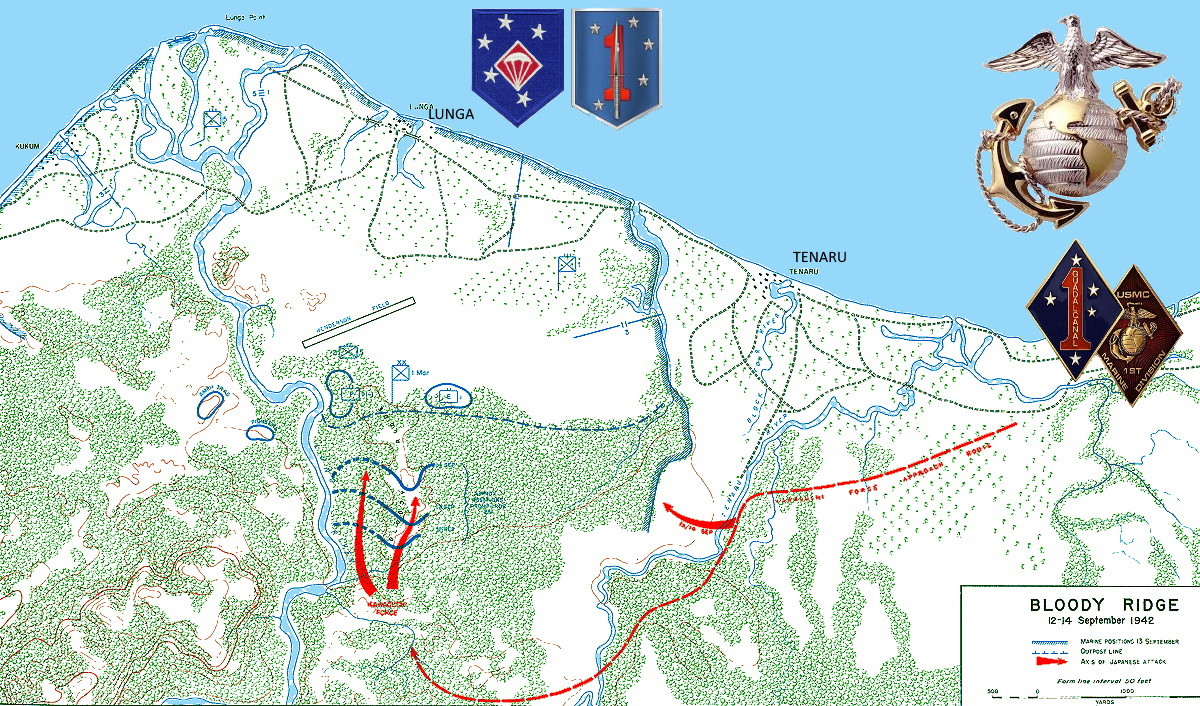

As August progressed it became clear that the Japanese were focusing their effort in the Solomons on regaining the vital airfield on Guadalcanal. The enemy poured fresh troops onto the island via the Tokyo Express a shuttle of ships and barges coming down the Slot each night. The 1st Marines destroyed the newly landed Ichiki Detachment along the Tenaru River on August 21, but the understrength Marine division had too few troops to secure the entire perimeter. To bolster his force, Gen Vandegrift brought the raiders over from Tulagi at the end of August and switched the paratroopers a few days later. The two battalions went into reserve in a coconut grove near Lunga Point.

As August progressed it became clear that the Japanese were focusing their effort in the Solomons on regaining the vital airfield on Guadalcanal. The enemy poured fresh troops onto the island via the Tokyo Express a shuttle of ships and barges coming down the Slot each night. The 1st Marines destroyed the newly landed Ichiki Detachment along the Tenaru River on August 21, but the understrength Marine division had too few troops to secure the entire perimeter. To bolster his force, Gen Vandegrift brought the raiders over from Tulagi at the end of August and switched the paratroopers a few days later. The two battalions went into reserve in a coconut grove near Lunga Point.

During this period Maj Miller took ill and went into the field hospital, as did other paratroopers. The shrinking battalion, temporarily commanded by a captain and down to less than 300 operational men, was so depleted in numbers and senior leadership that Vandegrift decided to attach them to Edson’s 1st Raider Battalion. The combined unit roughly equaled the size of a standard infantry battalion, though it still lacked the heavy firepower. Following the arrival of the first aviation reinforcements on August 20, the division made use of its daytime control of the skies to launch a number of seaborne operations. Near the end of the month, a battalion of the 5th Marines conducted an amphibious spoiling attack on Japanese forces to the west of the perimeter but inflicted little damage due to a lack of aggressive leadership. Two companies of raiders found no enemy after scouring Savo Island on September 4, while a mix-up in communications scrubbed a similar foray scheduled the next day for Cape Esperance.

During this period Maj Miller took ill and went into the field hospital, as did other paratroopers. The shrinking battalion, temporarily commanded by a captain and down to less than 300 operational men, was so depleted in numbers and senior leadership that Vandegrift decided to attach them to Edson’s 1st Raider Battalion. The combined unit roughly equaled the size of a standard infantry battalion, though it still lacked the heavy firepower. Following the arrival of the first aviation reinforcements on August 20, the division made use of its daytime control of the skies to launch a number of seaborne operations. Near the end of the month, a battalion of the 5th Marines conducted an amphibious spoiling attack on Japanese forces to the west of the perimeter but inflicted little damage due to a lack of aggressive leadership. Two companies of raiders found no enemy after scouring Savo Island on September 4, while a mix-up in communications scrubbed a similar foray scheduled the next day for Cape Esperance.