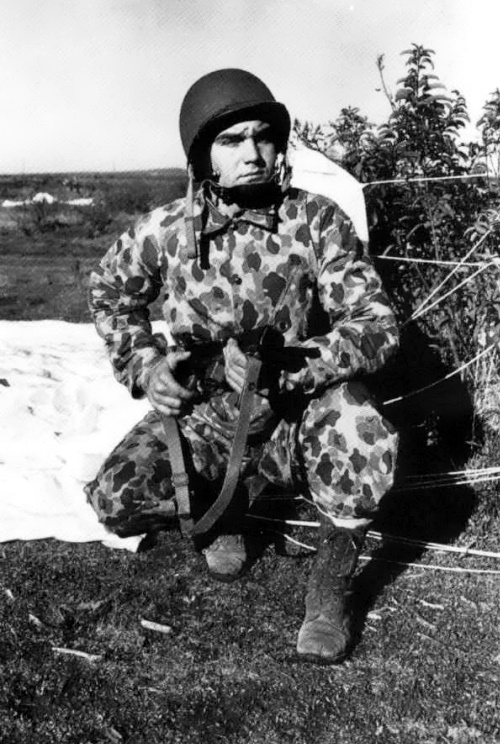

Once the jump master gave the signal, a man crouched in the doorway, made his exit dive, and then drew his knees toward his chest. The paratrooper, arms wrapped tightly about his chest chute, felt the opening shock of his main canopy almost immediately upon leaving the plane. If not, he had to pull the ripcord to deploy the reserve chute. (When jumping from blimps, the paratroopers had to use a ripcord for the main chute, too.)

Once the jump master gave the signal, a man crouched in the doorway, made his exit dive, and then drew his knees toward his chest. The paratrooper, arms wrapped tightly about his chest chute, felt the opening shock of his main canopy almost immediately upon leaving the plane. If not, he had to pull the ripcord to deploy the reserve chute. (When jumping from blimps, the paratroopers had to use a ripcord for the main chute, too.)

A parachutist’s speed of descent depended upon his weight, so Marines carried as little as possible to keep the rate down near 16 feet per second, the equivalent of jumping from a height of about 10 feet. At that speed, a jumper had to fall and roll when hitting the ground so as to spread the shock beyond his leg joints. Training jumps began at 1000 feet, while the standard height for tactical jumps in the Corps was 750. The Germans jumped from as low as 300 feet, but that made it impossible to open the emergency chute in time for it to be effective, which is probably the reason why they never used an emergency ‘reserve’ parachute.

A parachutist’s speed of descent depended upon his weight, so Marines carried as little as possible to keep the rate down near 16 feet per second, the equivalent of jumping from a height of about 10 feet. At that speed, a jumper had to fall and roll when hitting the ground so as to spread the shock beyond his leg joints. Training jumps began at 1000 feet, while the standard height for tactical jumps in the Corps was 750. The Germans jumped from as low as 300 feet, but that made it impossible to open the emergency chute in time for it to be effective, which is probably the reason why they never used an emergency ‘reserve’ parachute.

Throughout 1941, the Marine Corps produced just a trickle of jumpers and remained a long way from possessing a useful tactical entity. Most members of the first three training classes reported to the 2nd Marine Division in San Diego, to form the nucleus of the Corps’ first parachute unit. The 2nd Parachute Company (soon re-designated Able Co, 2nd Parachute Battalion) formally came into existence on March 22, 1941. The first commanding officer was Capt Robert H. Williams.

Throughout 1941, the Marine Corps produced just a trickle of jumpers and remained a long way from possessing a useful tactical entity. Most members of the first three training classes reported to the 2nd Marine Division in San Diego, to form the nucleus of the Corps’ first parachute unit. The 2nd Parachute Company (soon re-designated Able Co, 2nd Parachute Battalion) formally came into existence on March 22, 1941. The first commanding officer was Capt Robert H. Williams.

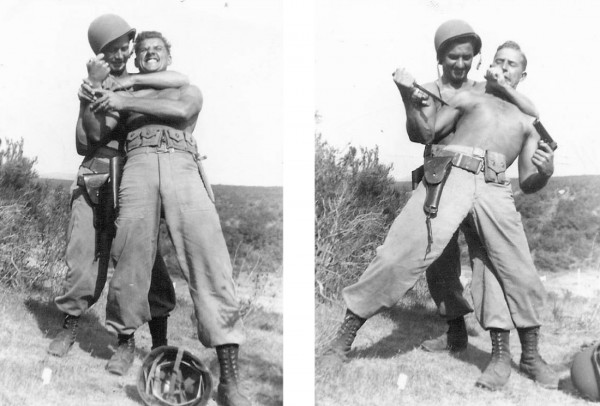

The majority of the fourth class went then to Quantico, and became the nucleus of Able Co, 1st Parachute Battalion, on May 28. Its first commanding officer was Capt Marcellus J. Howard. From that point forward, graduating classes were generally detailed on an alternating basis to each coast. In the summer of 1941, the West Coast company transferred to Quantico and merged into the 1st Battalion. Williams assumed command of the two-company organization. The concentration of the Corps’ small paratrooper contingents at Quantico at least allowed them to begin a semblance of tactical training. The battalion conducted a number of formation jumps during the last half of July, some from Marine planes and others from Navy patrol bombers. In no case could it muster enough planes to jump an entire company at once. Capt Williams used his battalion’s time on the ground to emphasize his belief that paratroopers are simply a new form of infantry. His men learned hand-to-hand fighting skills, went on conditioning hikes, and did a lot of calisthenic exercises. A Time magazine reporter noted that the paratroopers were a notably tough-looking outfit among Marines, who all look tough.

The majority of the fourth class went then to Quantico, and became the nucleus of Able Co, 1st Parachute Battalion, on May 28. Its first commanding officer was Capt Marcellus J. Howard. From that point forward, graduating classes were generally detailed on an alternating basis to each coast. In the summer of 1941, the West Coast company transferred to Quantico and merged into the 1st Battalion. Williams assumed command of the two-company organization. The concentration of the Corps’ small paratrooper contingents at Quantico at least allowed them to begin a semblance of tactical training. The battalion conducted a number of formation jumps during the last half of July, some from Marine planes and others from Navy patrol bombers. In no case could it muster enough planes to jump an entire company at once. Capt Williams used his battalion’s time on the ground to emphasize his belief that paratroopers are simply a new form of infantry. His men learned hand-to-hand fighting skills, went on conditioning hikes, and did a lot of calisthenic exercises. A Time magazine reporter noted that the paratroopers were a notably tough-looking outfit among Marines, who all look tough.

One of the battalion’s July jumps demonstrated the consternation that paratroopers could instill by their surprise appearance on a battlefield. A landing at an airfield near Fredericksburg (Virginia), unexpectedly disrupted maneuvers of the Army’s 44-ID, because its leaders thought the Marines were an aggressor force added to the problem without their knowledge. The same jump also indicated some of the limitations of airborne operations.

One of the battalion’s July jumps demonstrated the consternation that paratroopers could instill by their surprise appearance on a battlefield. A landing at an airfield near Fredericksburg (Virginia), unexpectedly disrupted maneuvers of the Army’s 44-ID, because its leaders thought the Marines were an aggressor force added to the problem without their knowledge. The same jump also indicated some of the limitations of airborne operations.

An approaching thunderstorm brought high winds that blew many of the jumpers away from their designated landing site and into a grove of trees. Luckily, none of the 40 men involved sustained any serious injuries.

OVERSEAS MODELS

Italy and the Soviet Union were among the first to demonstrate the military possibilities of airborne infantry in the 1930s with a series of maneuvers held in 1935 and 1936. Though somewhat crude, in fact, the Soviet paratroopers had to exit their slow-moving Tupolev TB-3 transporters through a hatch in the roof and then position themselves along with the wings to jump together. The exercise managed to land 1000 troops through air-drops followed by another 2500 soldiers with heavy equipment delivered via air landings. The gathered forces proceeded to carry out conventional infantry attacks with the support of heavy machine guns and light artillery. It is interesting to note that among the foreign observers present was Hermann Göring.

Beginning in the mid-1930s, several other European nations followed suit. Germany launched a particularly aggressive program, placing it in the air force under the command of a former World War One pilot, Kurt Student. The German paratroopers (Fallschirmjaeger) were complemented by glider units, an outgrowth of the sport gliding program that develops flying skills while Germany was under Versaille’s Treaty restrictions on rearmament.

Beginning in the mid-1930s, several other European nations followed suit. Germany launched a particularly aggressive program, placing it in the air force under the command of a former World War One pilot, Kurt Student. The German paratroopers (Fallschirmjaeger) were complemented by glider units, an outgrowth of the sport gliding program that develops flying skills while Germany was under Versaille’s Treaty restrictions on rearmament.

In 1940, Hitler had about 4500 Fallschirmjaeger at his disposal, organized into six battalions. Another 12.000 men formed an air infantry division designed as an air-landed follow-up to a parachute assault. The Luftwaffe (Air Force) had also a force of 700 Ju-52 transport planes available to carry these troops into combat. Each Junker-52 could hold up to 15 men with arms and ammunition.

The Soviet Union made the first combat use of parachute forces during the Winter War in Finland. At the beginning of the month of December 1939, as part of its initial abortive invasion, the Red Army dropped several dozen paratroopers near Petsamo behind the opposing lines. Apparently, Soviet paratroopers landed also, with machine guns, on the Karelian Isthmus, in the vicinity of Vilmannstrand about 70 km north-west of Viborg. The Red Army group of about 100 paratroopers were either killed or captured. Another report mentions a group of 200 Red Army paratroopers landing along the Finish-Norwegian Border, at Salminarji in the nickel mountains of northern Finland. After a short skirmish, all the members of this group were also killed or captured. Every Red Army tentative to drop paratroopers in Finland met equally disastrous fates.

The Soviet Union made the first combat use of parachute forces during the Winter War in Finland. At the beginning of the month of December 1939, as part of its initial abortive invasion, the Red Army dropped several dozen paratroopers near Petsamo behind the opposing lines. Apparently, Soviet paratroopers landed also, with machine guns, on the Karelian Isthmus, in the vicinity of Vilmannstrand about 70 km north-west of Viborg. The Red Army group of about 100 paratroopers were either killed or captured. Another report mentions a group of 200 Red Army paratroopers landing along the Finish-Norwegian Border, at Salminarji in the nickel mountains of northern Finland. After a short skirmish, all the members of this group were also killed or captured. Every Red Army tentative to drop paratroopers in Finland met equally disastrous fates.

Germany’s first use of airborne forces did not really achieve favorable results. In April 1940, as part of the invasion of Norway and Denmark, the Luftwaffe assigned a battalion of paratroopers to seize several key installations. The first group of Fallschirmjaeger captured the defended airbase of Sola, near Stavanger. The second group, an entire company, encountered its first defeat during the Norwegian Campaign. The paratroopers were dropped around the village and the railroad junction of Dombås on April 14, 1940, and after a five-day battle, the force was destroyed. During the German invasion of Poland in 1939, German Fallschirmjaegers were sent to occupy several airfields between the Vistula River and the Bug River. Although these operations were critical to German success in the campaign, they received little attention at the time, perhaps due to the much larger and bloodier naval battles that occurred along the Norwegian Coast. German airborne forces achieved spectacular success just one month later. One battalion breached Belgium’s heavily fortified defensive line during the offensive of May 1940.

Germany’s first use of airborne forces did not really achieve favorable results. In April 1940, as part of the invasion of Norway and Denmark, the Luftwaffe assigned a battalion of paratroopers to seize several key installations. The first group of Fallschirmjaeger captured the defended airbase of Sola, near Stavanger. The second group, an entire company, encountered its first defeat during the Norwegian Campaign. The paratroopers were dropped around the village and the railroad junction of Dombås on April 14, 1940, and after a five-day battle, the force was destroyed. During the German invasion of Poland in 1939, German Fallschirmjaegers were sent to occupy several airfields between the Vistula River and the Bug River. Although these operations were critical to German success in the campaign, they received little attention at the time, perhaps due to the much larger and bloodier naval battles that occurred along the Norwegian Coast. German airborne forces achieved spectacular success just one month later. One battalion breached Belgium’s heavily fortified defensive line during the offensive of May 1940.

In Holland, four battalions reinforced by two air infantry regiments captured three Dutch airfields, plus several bridges over rivers that bisected the German route of approach to the Hague (Holland) capital, and Rotterdam (Holland), its principal port. The airborne units held their ground in each case until the main assault forces arrived overland. The final parachute battalion, supported by two regiments of air infantry, landed near the Hague with the mission of decapitating the Dutch government and military high command. This force failed to achieve its goals but did cause considerable disruption. The last major German use of parachute assault came in May 1941. In the face of Allied control of the sea, Hitler launched an airborne invasion of the Mediterranean island of Crete. The objective was to capture three airfields for the ensuing arrival of air-landed reinforcements. Casualties were heavy among the first waves of 3000 men landed by parachute and glider, but others continued to pour in. Despite an overwhelming superiority in numbers, the 42.000 Allied defenders did not press their initial advantage.

Late in the second day, the Germans began landing transports on the one airstrip they held, even though it was under Allied artillery fire. After a few more days of bitter fighting, the Allied commander concluded that he was defeated and began to withdraw by sea. In the course of the battle, the Germans suffered 6700 casualties, half of them dead, out of a total force of 25.000. Allied losses on the island were less than 3500, although an additional 11.800 troops surrendered and another 800 soldiers died or were wounded at sea during the withdrawal.

Late in the second day, the Germans began landing transports on the one airstrip they held, even though it was under Allied artillery fire. After a few more days of bitter fighting, the Allied commander concluded that he was defeated and began to withdraw by sea. In the course of the battle, the Germans suffered 6700 casualties, half of them dead, out of a total force of 25.000. Allied losses on the island were less than 3500, although an additional 11.800 troops surrendered and another 800 soldiers died or were wounded at sea during the withdrawal.

The Allies decided that airborne operations were a powerful tactic, inasmuch as the Germans had leapfrogged 100 miles of British-controlled waters to seize Crete from a numerically superior ground force. As a consequence, the US and British armies would invest heavily in creating parachute and glider units. Hitler reached the opposite conclusion. Having lost 350 aircraft and nearly half of the 13.000 paratroopers engaged, he determined that airborne assaults were a costly tactic whose time had passed. The Germans never again launched a large operation from the air.

The first tactical employment of Marine parachutists came with the large-scale landing exercise of the Amphibious Force, Atlantic Fleet, in August 1941. This corps, under the command of Gen Holland M. Smith, consisted of the 1st Marine Division and the Army’s 1st Infantry Division. The final plan for the exercise at New River (North Carolina), called for Capt Williams’ company to parachute at H+1 onto a vital crossroads behind enemy lines, secure it, and then attack the rear of enemy forces opposing the landing of the 1st Infantry Division.

The first tactical employment of Marine parachutists came with the large-scale landing exercise of the Amphibious Force, Atlantic Fleet, in August 1941. This corps, under the command of Gen Holland M. Smith, consisted of the 1st Marine Division and the Army’s 1st Infantry Division. The final plan for the exercise at New River (North Carolina), called for Capt Williams’ company to parachute at H+1 onto a vital crossroads behind enemy lines, secure it, and then attack the rear of enemy forces opposing the landing of the 1st Infantry Division.

Capt Howard’s company would jump on the morning of D+2 in support of an amphibious landing by Col Merritt A. Edson’s Mobile Landing Group and a Marine tank company. Edson’s force (the genesis of the 1st Raider Battalion) would go ashore behind enemy lines, advance inland, destroy the opposing reserve force, and seize control of important lines of communication. Howard’s men would land near Edson’s objective and secure the road net and bridges in that vicinity. For the exercise, the parachutists were attached to the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, which operated from a small airfield at New Bern (North Carolina), just north of the Marine base. The landing force executed the operation as planned, but Holland Smith was not pleased with the results because there were far too many artificialities, including the lack of an aggressor force. A shortage of transport planes (only two on hand) handicapped the paratroopers; it took several flights, with long delays between, to get just one of the under-strength companies on the ground.

Once the exercise was underway, Smith made one attempt to simulate an enemy force. He arranged for Capt Williams to re-embark one squad and jump behind the lines of the two divisions, with orders to create as much havoc as possible. Williams’ tiny force cut tactical telephone lines, hijacked trucks, blocked a road, and successfully evaded capture for several hours. One after-action report noted that the introduction of paratroops lent realism to the necessity for command post security. Smith put great faith in the potential value of airborne operations. In his preliminary report on the exercise, he referred to Edson’s infantry-tank-parachute assault on D+2 as a spearhead thrust around the hostile flank and emphasized the need in modern warfare for the speed and shock effect of airborne and armor units.

With that in mind, he recommended that his two-division force include at least one air attack brigade of at least one parachute regiment and one air infantry regiment. (The term ‘air infantry’ referred to ground troops landed by transport aircraft – Glider). He also urged the Marine Corps to acquire the necessary transport planes. Despite this high-level plea, the Marine Corps continued to go slowly with the parachute program. At the end of March 1942, the 1st Battalion finally stood up its third line company, but the entire organization only had a total of 332 officers and men, less than 60 percent of its table of organization strength (one of the lowest figures in the division). The 2nd Battalion, still recovering from the loss of its first Able Co, had barely 200 men.

With that in mind, he recommended that his two-division force include at least one air attack brigade of at least one parachute regiment and one air infantry regiment. (The term ‘air infantry’ referred to ground troops landed by transport aircraft – Glider). He also urged the Marine Corps to acquire the necessary transport planes. Despite this high-level plea, the Marine Corps continued to go slowly with the parachute program. At the end of March 1942, the 1st Battalion finally stood up its third line company, but the entire organization only had a total of 332 officers and men, less than 60 percent of its table of organization strength (one of the lowest figures in the division). The 2nd Battalion, still recovering from the loss of its first Able Co, had barely 200 men.

Manpower and aircraft shortages and the straight jacket of the parachute training pipeline accounted for some of the bottlenecks, but a lack of enthusiasm for the idea at Headquarters also appears to have taken hold. By contrast, the Corps had not conceived the original idea for the raiders until mid-1941, but it had two full 800-man battalions in existence by March 1942. The Marine Corps was not enthusiastic about the latter force, either, but it expanded rapidly in large measure due to pressure from President Roosevelt and senior Navy leaders. Without similar heat from above, Headquarters was not about to commit its precious resources to a crash program to expand the paratroopers and provide them with air transports. Marine planners probably made a real choice in the matter, given the competing requirements to fill up divisions and air wings and make them ready for amphibious warfare, another infant art suffering through even greater growing pains.