Lidice: In Memoriam, Lidice uchytilova pomnik detskych obeti Lidice.

Lidice: In Memoriam, Lidice uchytilova pomnik detskych obeti Lidice.

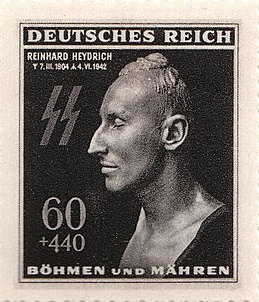

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich was norn in Halle and der Saale on Mar 7, 1904. He was SS-Obergruppenführer; General der Polizei; Chief of the Reich Security Office; Geheimstadtpolizei (Gestapo); Kriminalpolizei (Kripo); Sicherheitsdienst (SD); Stellvertretender Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia; President of the ICPC (Interpol); Main Architect of the Holocaust; Chairman in Jan 1942, of the Wannsee Conference and finally eliminated on Jun 4, 1942.

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich was norn in Halle and der Saale on Mar 7, 1904. He was SS-Obergruppenführer; General der Polizei; Chief of the Reich Security Office; Geheimstadtpolizei (Gestapo); Kriminalpolizei (Kripo); Sicherheitsdienst (SD); Stellvertretender Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia; President of the ICPC (Interpol); Main Architect of the Holocaust; Chairman in Jan 1942, of the Wannsee Conference and finally eliminated on Jun 4, 1942.

Many historians regard him as the darkest figure within the Nazi elite. Even Adolf Hitler himself, described him as the man with the iron heart. He was the founding head of the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the main German Intelligence Organization charged with seeking out and neutralizing resistance to the Nazi Party via arrests, deportations, and murders. He helped organize the 1938 Pogrom (Kristallnacht), a series of coordinated attacks against Jews throughout Nazi Germany and part of Austria on Nov 9/10 1938. This attacks, carried out by SA Stormtroopers and civilians, presaged the Holocaust.

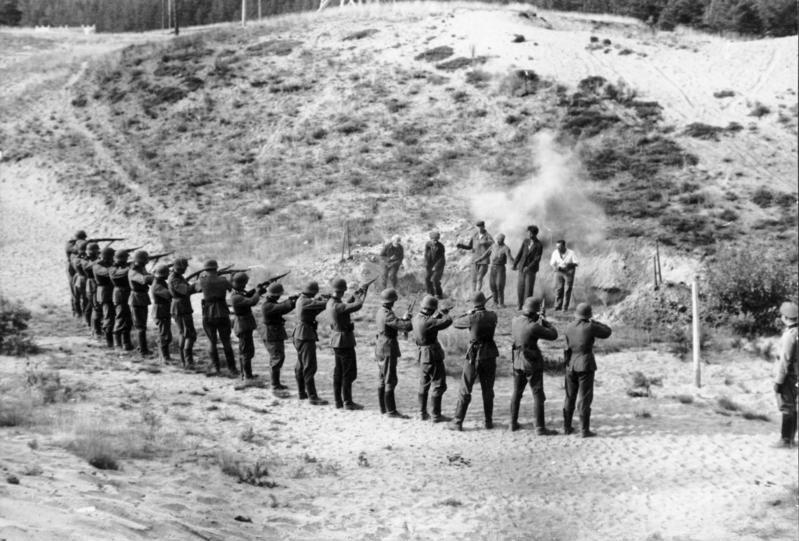

Upon his arrival in Prague, Heydrich sought to eliminate opposition to the Nazi occupation by suppressing Czech culture and deporting and executing members of the Czech resistance. He was directly responsible for the Einsatzgruppen, the special task forces which traveled in the wake of the German armies and murdered over one million people, including Jews, by mass shooting. Heydrich was eliminated in Prague on May 27, 1942, by a British-trained team of Czech and Slovak soldiers who had been sent by the Czechoslovak government in exile to kill him during Operation Anthropoid. He died from his injuries a week later. Intelligence falsely linked the assassins to the villages of Lidice and Ležáky. Lidice was erased from the map; all men and boys over the age of 16 were shot, and all but a handful of its women and children were deported and killed in Nazi concentration camps.

Upon his arrival in Prague, Heydrich sought to eliminate opposition to the Nazi occupation by suppressing Czech culture and deporting and executing members of the Czech resistance. He was directly responsible for the Einsatzgruppen, the special task forces which traveled in the wake of the German armies and murdered over one million people, including Jews, by mass shooting. Heydrich was eliminated in Prague on May 27, 1942, by a British-trained team of Czech and Slovak soldiers who had been sent by the Czechoslovak government in exile to kill him during Operation Anthropoid. He died from his injuries a week later. Intelligence falsely linked the assassins to the villages of Lidice and Ležáky. Lidice was erased from the map; all men and boys over the age of 16 were shot, and all but a handful of its women and children were deported and killed in Nazi concentration camps.

Operation Anthropoid – Heydrich Assassination

On May 29 1942, Radio Prague announced that SS-Obergruppenführer Heydrich, the Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia, was dying; assassins had wounded him fatally. On Jun 6, he died. Though not yet forty at his death, the blond Heydrich had had a notable career. As a Free Corpsman in his teens he was schooled in street fighting and terrorism. Adulthood brought him a commission in the German navy, but he was cashiered for getting his fiancee pregnant and then refusing to marry her because a woman who gave herself lightly was beneath him. He then worked so devotedly for the Nazi Party that, when Hitler came to power, he put Heydrich in charge of the Dachau Concentration Camp.

In 1934, he headed the Berlin Gestapo. On Jun 30, at the execution of Gregor Strasser, the bullet missed the vital nerve and Strasser lay bleeding from the neck. Heydrich’s voice was heard from the corridor: Not dead yet? Let the swine bleed to death! In 1936, Heydrich became chief of the SIPO, which included the criminal police, the security service, and the Gestapo. In 1938, he concocted the idea of the Einsatzgruppen, whose business was to murder Jews.

The results were brilliant. In two years these 3000 men slaughtered at least a million persons. In Nov of that year, he was involved in an event that in some inverted fashion presaged his own death. The son of a Jew whom he had deported from Germany assassinated Ernst von Rath in Paris. In reprisal Heydrich ordered a pogrom, and on the night of Nov 9, 20.000 Jews were arrested in Germany. In 1939, the merger of the SIPO with the SS Main Security Office made Heydrich the leader of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt. In this capacity he ordered and supervised the Polish Attack on Gleiwitz, an important detail in the stage setting for the invasion of Poland on Sept 1. It was he who saw to it that twelve or thirteen criminals dressed in Polish uniforms would be given fatal injections and found dead on the battlefield. It was probably he who chose the code name for these men – Canned Goods.

The results were brilliant. In two years these 3000 men slaughtered at least a million persons. In Nov of that year, he was involved in an event that in some inverted fashion presaged his own death. The son of a Jew whom he had deported from Germany assassinated Ernst von Rath in Paris. In reprisal Heydrich ordered a pogrom, and on the night of Nov 9, 20.000 Jews were arrested in Germany. In 1939, the merger of the SIPO with the SS Main Security Office made Heydrich the leader of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt. In this capacity he ordered and supervised the Polish Attack on Gleiwitz, an important detail in the stage setting for the invasion of Poland on Sept 1. It was he who saw to it that twelve or thirteen criminals dressed in Polish uniforms would be given fatal injections and found dead on the battlefield. It was probably he who chose the code name for these men – Canned Goods.

At this time, Bohemia and Moravia had already been raised from independent status to that of Reichsprotektorat with Baron von Neurath, Germany’s now senile former foreign minister, designated the Protector – of the Czechs from themselves, presumably. But a greater honor was in store for them. On Sept 3, 1941, when von Neurath was replaced by SS-Obergruppenführer Heydrich. The hero moved into the Hradcany Palace in Prague and the executions started, 300 in the first five weeks. His lament for Gregor Strasser became his elegy for all patriotic Czechs: Aren’t they dead yet? Let them bleed to death! He had come a long way in thirty-eight years. The son of a music teacher whose wife was named Sarah, Reinhard had gone on trial three times because of Party doubts  about the purity of his Aryan origin. Now, as chief of the RSHA (Reichssicherheitshauptamt), which he continued to run from Czechoslovakia, he was Hangman to all occupied Europe. His power was such that he could force Admiral Canaris to come to Prague and at the end of May 1942, sign the independence of the Abwehr and accept subordination to the Sicherheitsdienst. It was his moment of sweetest triumph. A few weeks later he was dead and Himmler pronounced the funeral oration calling him that good and radiant man. So much for the story we all know, and on to questions left unanswered by it.

about the purity of his Aryan origin. Now, as chief of the RSHA (Reichssicherheitshauptamt), which he continued to run from Czechoslovakia, he was Hangman to all occupied Europe. His power was such that he could force Admiral Canaris to come to Prague and at the end of May 1942, sign the independence of the Abwehr and accept subordination to the Sicherheitsdienst. It was his moment of sweetest triumph. A few weeks later he was dead and Himmler pronounced the funeral oration calling him that good and radiant man. So much for the story we all know, and on to questions left unanswered by it.

Operation Anthropoid was the code name for the assassination of SS-Obergruppenführer u. Gen der Polizei Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (Reich Main Security Office, RSHA), the combined security services of Nazi Germany, and acting Reichsprotektor of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The operation had to be carried out in Prague on or around May 27, 1942, being prepared by the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) with the approval of the London exiled Czechoslovak government.

Who were Heydrich’s assassins? Who could successfully plan his death? Was the motive simply revenge for suffering? How was it accomplished? And the hardest question of all, was it a good thing?

Here, for the first time, are the answers to all these but the last, and on that question stuff for pondering.

When Heydrich took charge of Bohemia and Moravia, the Czechs learned what it means to live under a master of suppression. The war fronts were far away, it was the period of smashing German successes in the Balkans, Scandinavia, France, and the USSR. The Czechs heard little that Heydrich did not want them to hear. Their underground movement was systematically penetrated and all but destroyed. On Oct 3, 1941, for example, the capture of a single Czech radio operator by Heydrich’s men led to the arrest of 73 agents working for Moscow. Underground radio contact with London was monitored. The Czechs were losing heart. In London the strength of the resistance in all occupied countries was periodically reviewed, and the countries were listed in the order of the assistance each gave the Allied cause. In 1941, Czechoslovakia was always ranked at the very end. Eduard Benes, its president-in-exile, was deeply embarrassed. He was also gravely concerned that the Allies, if his people failed to fight, might give short shrift to any Czech claims after the war.

He told his intelligence chief, Gen Frantisek Moravec, to order an intensification of resistance activity. But it was difficult enough to get even a parachuted courier or coded radio message past the wary  Heydrich. Nothing happened in response. Then President Benes hit upon the idea of contriving to assassinate a prominent Nazi or Quisling inside the tight dungeon of the Protectorate; such a bold stroke would refurbish the Czech people’s prestige and advance the status of their government in London.

Heydrich. Nothing happened in response. Then President Benes hit upon the idea of contriving to assassinate a prominent Nazi or Quisling inside the tight dungeon of the Protectorate; such a bold stroke would refurbish the Czech people’s prestige and advance the status of their government in London.

The German retaliation would be brutal, of course, but its brutality might serve to inflame Czech patriotism. Who should be the target? Gen Moravec first nominated the most prominent of the Czech collaborators, an ex-colonel whose fawning subservience to his Teutonic masters left the London Czechs nauseated and ashamed.

The general also had a personal reason for his choice, the name of the Czech Quisling was Emanuel Moravec, a coincidence that had plagued the general for years. But Emanuel, called the Greasy, was not the right man for the purpose. He was not well known abroad, and Czech prestige would not be raised significantly by crushing a worm.

The Germans, too, were likely to regard his death as no great loss; he was only a minister of education, easy to replace, and even the Nazis despised traitors. Heydrich was totally different. His unique combination of brilliance and brutality had no peer even in the Third Reich. He had been personally responsible for the execution of hundreds of Czechs and the imprisonment of thousands.

The shot that killed him would be heard in every capital of the world. There could be no other choice. Gen Moravec so recommended, President Benes agreed, and the planning of Operation Salmon began in tense secrecy.

The shot that killed him would be heard in every capital of the world. There could be no other choice. Gen Moravec so recommended, President Benes agreed, and the planning of Operation Salmon began in tense secrecy.

Wanted, Men for Martyrdom

The first problem was finding one or two men who could and would do the job. It must have seemed to Gen Moravec, at least at the outset, an almost impossible task. The many Czech politicians in London were preoccupied in the unending scramble for posts in the provisional government. There were quite a few Czech businessmen in England, but most of them were too busy making a fast fortune to be interested. There were brave and patriotic Czechs serving in fighter and bomber wings attached to the Royal Air Force, but the Air Ministry would never let them go. And so the choice narrowed to the single infantry brigade of about 2500 men encamped near Cholmondeley in England. This pool of prospects had its own disadvantages. An encampment of 2500 is like a town of that size. Everyone knows everyone else and is full of curiosity about everything that anyone does. Here this inquisitiveness was also undissipated by outside contacts, the Czech soldiers speaking little or no English and having few interests beyond the limits of the camp.

Each transfer, trip, or trifle thus became news, something to discuss and  analyze. For screening purposes the personnel files of the brigade contained only what each man had told about himself or, in rare instances, about others whom he had known earlier, at home. There was no way to check police files, run background or neighborhood checks, or otherwise obtain independent verification of loyalties. Under such circumstances it is a tribute to Gen Ingr, Minister of Defense in the exiled government, to Gen Moravec, and to their subordinates that of 153 parachutists flown from England and dropped into Czechoslovakia, only three proved turncoats. How many people would have to know? President Benes; Gen Ingr, Gen Moravec and his deputy, Lt Col Stragmueller and Maj Fryc, chief of operations!

analyze. For screening purposes the personnel files of the brigade contained only what each man had told about himself or, in rare instances, about others whom he had known earlier, at home. There was no way to check police files, run background or neighborhood checks, or otherwise obtain independent verification of loyalties. Under such circumstances it is a tribute to Gen Ingr, Minister of Defense in the exiled government, to Gen Moravec, and to their subordinates that of 153 parachutists flown from England and dropped into Czechoslovakia, only three proved turncoats. How many people would have to know? President Benes; Gen Ingr, Gen Moravec and his deputy, Lt Col Stragmueller and Maj Fryc, chief of operations!

Of these, President Benes and Gen Ingr needed to know only the purpose of the operation and the names of the men chosen to carry it out. Others, required for instruction, would necessarily know that certain men were entering Czechoslovakia to carry out a clandestine action, but not their precise intent. Four instructors would be needed, experts respectively in parachute work, in the terrain of the area, in cover, documentation, clothing, and equipment, and in commando techniques. Several British officers, representatives of MI-6, would participate in this training. The crew of the plane carrying the men into Czechoslovakia would know where and when they were going, though not their identities or mission. And finally, a large number of men in the brigade personally acquainted with the candidates could be expected to make guesses of varying degrees of accuracy as the preparations for assassination progressed.

Because the number of persons who would be partly or fully informed was so unavoidably much too large, it was essential that the men finally chosen should be as discreet as they were brave. Of the 2500 Czech soldiers in the brigade some 700, most of them volunteers, were already engaged in parachute training under British instruction. Two officers were assigned to the brigade, one to the parachutists and the other to the ground troops, ostensibly as aides but actually as spotters. These two officers knew only that they were to choose the best candidates for a dangerous assignment. Men recommended by the spotters were interviewed singly by Lt Col Stragmueller. Some were asked whether they would volunteer for special training. Almost all those asked agreed, and they were sent in groups of ten for vigorous physical conditioning and thorough schooling in commando tactics – the use of a wide assortment of small arms, the manufacture of home-made bombs, ju-jitsu, cover and concealment, and the rest. During this intensive drilling the ten-man teams were kept under close observation. It was essential to discover not only the bravest and most capable but also – it having been decided that the assassination was a two-man job – those who worked best in pairs. Other considerations also came into play; men from Prague, for example, were automatically eliminated because of the danger of recognition after arrival.

By now the choice had narrowed to eight men in half as many groups. Gen Moravec visited these four groups, along with all the others, on a regular schedule. On his orders the instructors drew the eight candidates aside one at a time and passed each a piece of juicy, concocted information with the warning not to mention it to anyone. Each tidbit was different. Soon two new rumors were circulating, and two men were eliminated. One of the remaining six was disqualified by marriage; another was suddenly incapacitated by illness. Gen Moravec interviewed the remaining four. Two of them, non-coms, met all tests and were also good friends. Their names were Jan Kubis and Josef Gabcik.

By now the choice had narrowed to eight men in half as many groups. Gen Moravec visited these four groups, along with all the others, on a regular schedule. On his orders the instructors drew the eight candidates aside one at a time and passed each a piece of juicy, concocted information with the warning not to mention it to anyone. Each tidbit was different. Soon two new rumors were circulating, and two men were eliminated. One of the remaining six was disqualified by marriage; another was suddenly incapacitated by illness. Gen Moravec interviewed the remaining four. Two of them, non-coms, met all tests and were also good friends. Their names were Jan Kubis and Josef Gabcik.

Kubis was born in Southern Moravia in 1916. After some ten years of schooling he had gone to work as an electrician. He had been in the Czech Army since 1936 and had fought in France in 1940. His excellent physical condition made his 160 pounds, at 5’9″, look lean. Slow of movement, taciturn, and persevering, he was also intelligent and inventive. Gabcik was a year younger than Kubis. An orphan from the age of ten, he too had left school at sixteen. After working as a mechanic for four years, he had entered the Czech Army in 1937. He had been given the Croix de Guerre in France in 1940. He was strong and stocky, an excellent soccer player, and like Kubis lean for all his 150 pounds on a 5’8″ frame. His blue eyes were expressive, and his whole face unusually mobile. Talented and clever, good natured, cheerful even under strenuous or exasperating circumstances, frank and cordial, he was an excellent counterpoise for the quieter, more introverted Kubis. Both men had gone through the arduous training without illness or complaint. Both spoke fluent German. Both were excellent shots. General Moravec spoke separately to each of them.

Kubis was born in Southern Moravia in 1916. After some ten years of schooling he had gone to work as an electrician. He had been in the Czech Army since 1936 and had fought in France in 1940. His excellent physical condition made his 160 pounds, at 5’9″, look lean. Slow of movement, taciturn, and persevering, he was also intelligent and inventive. Gabcik was a year younger than Kubis. An orphan from the age of ten, he too had left school at sixteen. After working as a mechanic for four years, he had entered the Czech Army in 1937. He had been given the Croix de Guerre in France in 1940. He was strong and stocky, an excellent soccer player, and like Kubis lean for all his 150 pounds on a 5’8″ frame. His blue eyes were expressive, and his whole face unusually mobile. Talented and clever, good natured, cheerful even under strenuous or exasperating circumstances, frank and cordial, he was an excellent counterpoise for the quieter, more introverted Kubis. Both men had gone through the arduous training without illness or complaint. Both spoke fluent German. Both were excellent shots. General Moravec spoke separately to each of them.

He explained that the mission had the one purpose of assassinating Heydrich. He stressed to each of the young men the great likelihood that he would be caught and executed. Escape from encircled Czechoslovakia after Heydrich had been killed would be practically impossible. And the survival of either, hiding inside the country until the war ended, was extremely unlikely. The probability was that both would be killed at the scene of action.

Although neither man had relatives or friends in Prague, both had relatives in the countryside; and the general reminded them of what had happened to the family of a Czech sent from London on a successful clandestine mission to Italy. Somehow the Gestapo had learned his identity and executed all of his relatives in Czechoslovakia, even first and second cousins. Please understand, General Moravec told each of them, that I am not testing you now. You have proved that you are brave and patriotic. I am telling you that acceptance of this mission is almost certainly acceptance of death – perhaps a very painful and degrading death – because I do not believe that the man who tries to kill Heydrich can succeed if the awful realization that he too will die comes too late, and unnerves him. I have another reason, too : if you make your choice with open eyes, I shall sleep a little better.

Although neither man had relatives or friends in Prague, both had relatives in the countryside; and the general reminded them of what had happened to the family of a Czech sent from London on a successful clandestine mission to Italy. Somehow the Gestapo had learned his identity and executed all of his relatives in Czechoslovakia, even first and second cousins. Please understand, General Moravec told each of them, that I am not testing you now. You have proved that you are brave and patriotic. I am telling you that acceptance of this mission is almost certainly acceptance of death – perhaps a very painful and degrading death – because I do not believe that the man who tries to kill Heydrich can succeed if the awful realization that he too will die comes too late, and unnerves him. I have another reason, too : if you make your choice with open eyes, I shall sleep a little better.

First Gabcik and then Kubis agreed, thoughtfully but without hesitation or bravado. Both were quietly proud to have been chosen. The general then brought them together and explained that from that moment on they would be separated from all the rest, the final preparations would be made in strictest seclusion. If at any moment either man felt that he could not go through with the assassination, he was bound in duty and honor to say so immediately, without false shame. They glanced at each other. No, said Gabcik. We want to do it. Kubis just nodded.

Some training was still needed. Kubis had to learn to ride a bicycle. Both had to know Prague as though they had spent years walking its streets and alleys. Both needed instruction in withstanding hostile interrogation. Both had to memorize all the details of separate cover stories which could be confessed, after initial resistance, to the Gestapo. On the last day of training they were each given a lethal dose of cyanide and told how to conceal it on their persons. It was the last defense against torture. One more point, Gen Moravec told them, under no circumstances – and I mean none at all – is either of you to get in touch with the underground, directly or indirectly. You are absolutely on your own. The underground is infested with informants; Heydrich has done his usual masterful job. For this reason we have not sent out one word about you, even to the most trusted leaders there. If anyone approaches you and says that he comes from the underground, he is a provocateur. Treat him as such. The men nodded. Don’t forget, the general insisted.

Some training was still needed. Kubis had to learn to ride a bicycle. Both had to know Prague as though they had spent years walking its streets and alleys. Both needed instruction in withstanding hostile interrogation. Both had to memorize all the details of separate cover stories which could be confessed, after initial resistance, to the Gestapo. On the last day of training they were each given a lethal dose of cyanide and told how to conceal it on their persons. It was the last defense against torture. One more point, Gen Moravec told them, under no circumstances – and I mean none at all – is either of you to get in touch with the underground, directly or indirectly. You are absolutely on your own. The underground is infested with informants; Heydrich has done his usual masterful job. For this reason we have not sent out one word about you, even to the most trusted leaders there. If anyone approaches you and says that he comes from the underground, he is a provocateur. Treat him as such. The men nodded. Don’t forget, the general insisted.

And now, a review! Kubis, where does Heydrich have his office? Prague Palace. Show me on the map. Kubis did so without hesitation. Gabcik, where do you land? Here sir, said Gabcik, pointing to another spot some 50 kilometers southeast of Prague, an area chosen because it was wooded, rolling, and offered good approaches to the city. Kubis, what do you do first, after touching ground and removing parachutes? We destroy all traces of the descent, sir. Do you proceed to the palace Gabcik? No. It is too heavily guarded.

All visitors are thoroughly checked. His private residence? The same, sir. Kubis, where do you go? Here sir. Kubis’ finger pointed to a spot half way between Prague and the village of Brezary. Gabcik, when does Heydrich pass this spot? Daily, sir, going into the city, and at night on his return. We shall observe the time. Why have we chosen this particular spot on the road? Sir, there is a sharp curve. His car and the motorcycles must slow down to twenty kilometers. How many motorcycles, Kubis? Probably two, sir. We’ll find out.

All visitors are thoroughly checked. His private residence? The same, sir. Kubis, where do you go? Here sir. Kubis’ finger pointed to a spot half way between Prague and the village of Brezary. Gabcik, when does Heydrich pass this spot? Daily, sir, going into the city, and at night on his return. We shall observe the time. Why have we chosen this particular spot on the road? Sir, there is a sharp curve. His car and the motorcycles must slow down to twenty kilometers. How many motorcycles, Kubis? Probably two, sir. We’ll find out.

Good. Now remember – don’t rush it. Don’t use pistols in any case. If there is any chance that you can’t bring it off with the bomb or the machine gun on the first try, wait and pick a better spot for the next day. But don’t delay too long. Now, a last dry run. The two men left. Gen Moravec waited for ten minutes, summoned his car, and asked to be driven down a certain country road at normal speed. He sat in the back, with binoculars, closely scanning all the foliage and other cover wherever the car slowed for a curve. Then he drove back and waited. Soon Gabcik and Kubis reappeared. Well? the general demanded. Did you kill me? Yes, sir. Are you sure? Yes, sir. Good.

The escape was planned with equal care. The men would make their way, mostly on foot, to Slovakia, where the German pressure was far less severe. Gabcik, who knew the mountains of Slovakia well, had chosen a safe area where none of his friends or relatives lived. For food they were on their own.

The escape was planned with equal care. The men would make their way, mostly on foot, to Slovakia, where the German pressure was far less severe. Gabcik, who knew the mountains of Slovakia well, had chosen a safe area where none of his friends or relatives lived. For food they were on their own.

Early April was all fog, wind, and rain. Normally Czech, Polish, and Canadian crews took turns flying paratroopers over Czechoslovakia, but Gen Ingr had made sure that a Czech team, Capt Anderle and his crew, would be rested and ready for a good day. The fifteenth, at last, dawned clear and still. Gen Moravec walked to the plane with his two chosen men. They stood at the bottom of the ramp. He looked at them, and they at him, in silence. No speeches, no cheek-kissing, no wet eyes. Gabcik and Kubis seemed as impassive as two farmers starting the day’s work. They shook hands briefly. The general went into the plane and briefed its captain and crew. When he came out, he found Gabcik suddenly flustered. Sir, may I speak to you for a moment in private? The general thought sadly. Well, better for it to happen now. We shall have to send him to the Isle of Man until the war ends. Of course, Gabcik, he said, and moved some yards away.

Gabcik followed, uncomfortable. He said, look, sir, I don’t know how to tell you this, I’m ashamed. But I have to tell you. I’ve run up a bill at a restaurant, the Black Boar. I’m afraid it’s ten pounds, sir. Could you have it taken care of? I hate to ask, but I haven’t got the money, and I don’t want to leave this way. All right, Moravec managed. Anything else? Gabcik was relieved. No, sir, he said, except don’t worry. We’ll pull it off, Kubis and I. They climbed in, then, and the plane started down the runway. The general thought of all the courageous men he’d known. No, he said out loud. None of them were braver. He felt full of pride and pain.

Gabcik followed, uncomfortable. He said, look, sir, I don’t know how to tell you this, I’m ashamed. But I have to tell you. I’ve run up a bill at a restaurant, the Black Boar. I’m afraid it’s ten pounds, sir. Could you have it taken care of? I hate to ask, but I haven’t got the money, and I don’t want to leave this way. All right, Moravec managed. Anything else? Gabcik was relieved. No, sir, he said, except don’t worry. We’ll pull it off, Kubis and I. They climbed in, then, and the plane started down the runway. The general thought of all the courageous men he’d known. No, he said out loud. None of them were braver. He felt full of pride and pain.

Death Rides in Spring

Capt Anderle came back on schedule. He reported that the two men had teased his crew about having to go back to the strangeness of England instead of coming home. At the command they had jumped unhesitatingly. So the waiting started. Gabcik and Kubis had not taken a transmitter or any means to report back but if they were successful everybody would know it. None of the anxious witting talked about the operation.

On the tenth day Capt Anderle was shot down and killed in an air battle at Malta. I am not a superstitious man, Gen Moravec told himself. Two weeks, three weeks, four. It must have gone wrong.

If they failed, said Gen Ingr, let us hope they failed completely, without getting anywhere near Heydrich. Six weeks, and May 29, Friday afternoon, Prague radio, indignant, reported that Reichsprotektor Reinhard Heydrich had been severely wounded by murderers in a criminal, bastardly attempt upon his life that very morning. They had thrown a bomb into the Protector’s car. Two men had been seen leaving the spot on bicycles. The search for them was under way. They would be found. The news exploded in the international press. At home and abroad, Czechs stood a little straighter. Several authentic inside stories were printed. The favorite was that the Czech underground had struck. Scarcely less popular was the tale that the Abwehr had killed Heydrich because of the humiliating agreement he had just forced Canaris to sign.

If they failed, said Gen Ingr, let us hope they failed completely, without getting anywhere near Heydrich. Six weeks, and May 29, Friday afternoon, Prague radio, indignant, reported that Reichsprotektor Reinhard Heydrich had been severely wounded by murderers in a criminal, bastardly attempt upon his life that very morning. They had thrown a bomb into the Protector’s car. Two men had been seen leaving the spot on bicycles. The search for them was under way. They would be found. The news exploded in the international press. At home and abroad, Czechs stood a little straighter. Several authentic inside stories were printed. The favorite was that the Czech underground had struck. Scarcely less popular was the tale that the Abwehr had killed Heydrich because of the humiliating agreement he had just forced Canaris to sign.

At Cholmondeley, the brigade buzzed. The absent Gabcik and Kubis were talked about, of course; but they had been gone for a long time. And so had many more paratroopers dispatched on one mission or another. There was no reason to pick out these two over others who had never returned. Lt Opalka, for example. He had been gone for five months now. And three men had left the camp just a week before Heydrich was killed. The battalion talked of little else. One sergeant, a little older than the others, was convinced that the man who took care of Heydrich was a non-com named Anton Kral. Kral? repeated one of the others. Why Kral? He’s been gone as long as Opalka. I don’t know, the sergeant answered. It’s just a feeling. Remember how tall and dark he was, and silent? And brave, said another. He fought well in France. Well, shrugged a third, it could be anybody. Perhaps the sergeant knew more than the others about Anton Kral. Kral had been picked by Gen Moravec to be parachuted with Lt Opalka into an area northeast of Prague. Their mission was to get in touch with the underground there to deliver instructions. Nothing had been heard from either of them since their departure, and they were presumed lost.

In Prague, Heydrich was dying. The three physicians summoned from Berlin – Gebhardt, Morell, and Brandt – tried hard, but could not save him. Himmler was there too, full of public sorrow, privately perhaps rejoicing. He had his funeral oration down pat before the sixth of June, when Heydrich died. And he seized the chance to direct personally the search for the assassins and the massive reprisals. First, martial law was proclaimed over all Bohemia and Moravia. A rigid daily curfew at sundown was imposed. Throughout the land public announcements proclaimed that anyone who harbored the assassins or otherwise aided them in any way would be executed summarily and without trial. The illegal possession of arms and even approval of assassination in principle were declared capital crimes. Himmler’s chief executive in the subsequent action was the notorious Sudeten German, Deputy Reichsprotektor Karl Hermann Frank. The mass arrests and mass executions began.

In Prague, Heydrich was dying. The three physicians summoned from Berlin – Gebhardt, Morell, and Brandt – tried hard, but could not save him. Himmler was there too, full of public sorrow, privately perhaps rejoicing. He had his funeral oration down pat before the sixth of June, when Heydrich died. And he seized the chance to direct personally the search for the assassins and the massive reprisals. First, martial law was proclaimed over all Bohemia and Moravia. A rigid daily curfew at sundown was imposed. Throughout the land public announcements proclaimed that anyone who harbored the assassins or otherwise aided them in any way would be executed summarily and without trial. The illegal possession of arms and even approval of assassination in principle were declared capital crimes. Himmler’s chief executive in the subsequent action was the notorious Sudeten German, Deputy Reichsprotektor Karl Hermann Frank. The mass arrests and mass executions began.

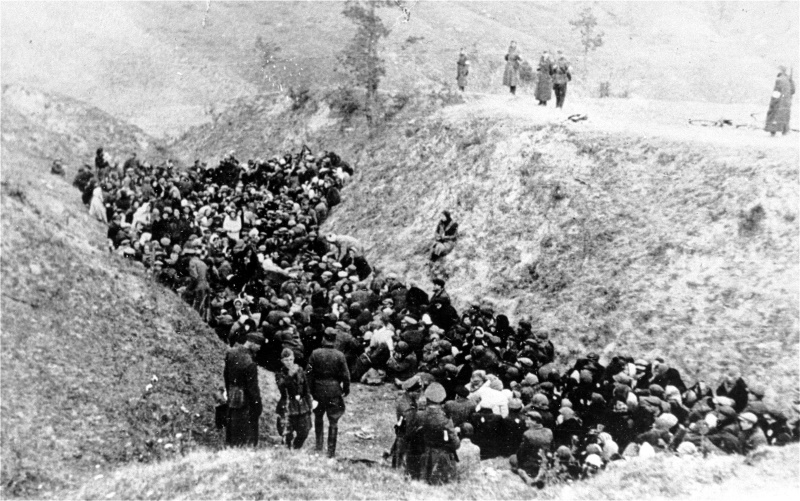

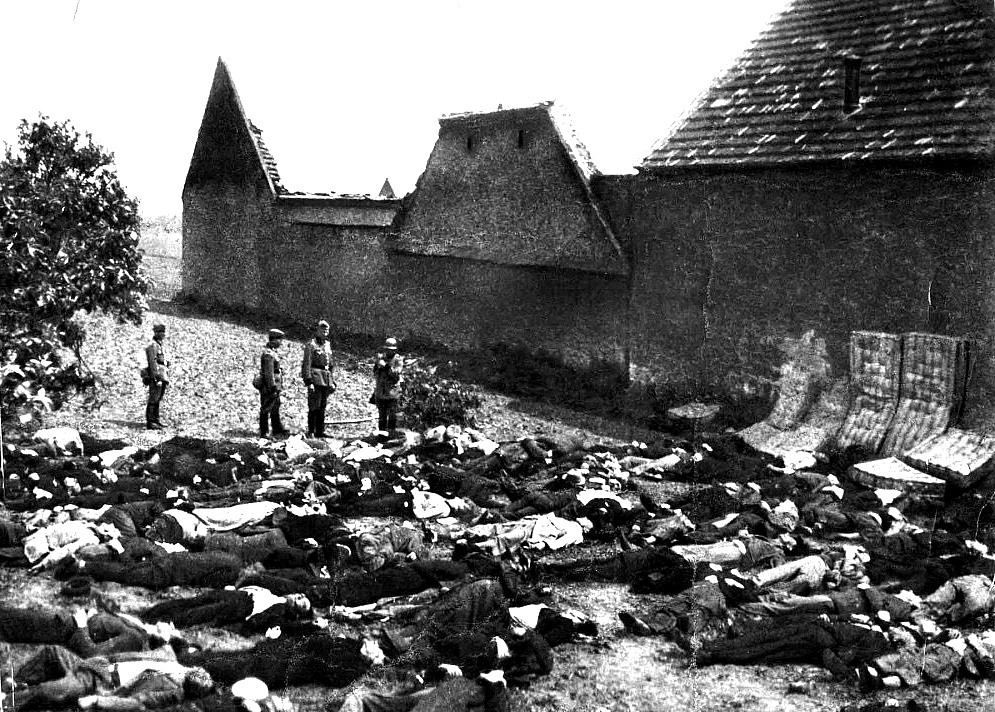

Czechs were killed without investigation, without trial, even without interrogation, usually on the basis of some vague or distorted denunciation. For twenty days the slaughter continued. But neither terror nor the special Gestapo details dispatched to Prague could bring the assassins to light. Then Himmler and Frank had a new idea. Quite arbitrarily, they chose a small settlement near Kladno, fifteen miles from Prague. On Jun 9, Col Rostock marched a military detail into this village of the now memorable name, Lidice. Every male not unquestionably a child was slaughtered. Even the few who chanced to be absent were run down and killed – two hundred men and boys in all. The women were driven into concentration camps.

Czechs were killed without investigation, without trial, even without interrogation, usually on the basis of some vague or distorted denunciation. For twenty days the slaughter continued. But neither terror nor the special Gestapo details dispatched to Prague could bring the assassins to light. Then Himmler and Frank had a new idea. Quite arbitrarily, they chose a small settlement near Kladno, fifteen miles from Prague. On Jun 9, Col Rostock marched a military detail into this village of the now memorable name, Lidice. Every male not unquestionably a child was slaughtered. Even the few who chanced to be absent were run down and killed – two hundred men and boys in all. The women were driven into concentration camps.

The children were shipped off to Germany. Everything above ground, all structures, were razed, and the ground was ploughed. Lidice became a blank, a field of regular brown furrows. And still there was no trace of the killers of Heydrich. So they did the same thing to another hamlet, Lezaky, in southwestern Bohemia.

The children were shipped off to Germany. Everything above ground, all structures, were razed, and the ground was ploughed. Lidice became a blank, a field of regular brown furrows. And still there was no trace of the killers of Heydrich. So they did the same thing to another hamlet, Lezaky, in southwestern Bohemia.

The killers were not found

On Jun 24, Frank officially announced that if the assassins were not turned over in 48 hours, the population of Prague would be decimated. He also used a carrot – 1 million Reich Marks for anyone giving information leading to the death or capture of the wanted men. This worked, apparently. On Jun 25, Radio Prague reported that the culprits had been discovered in the basement of the St Bartholomeus Orthodox Church on Reslova Street. Encirclement was under way and capture only a matter of hours. In London the listeners knew that Gabcik and Kubis were fighting back. The following day the radio said the fight was over; the assassins were dead. There were four of them, the announcer said flatly, one Gabcik, one Kubis, a certain Opalka, and a man known as Josef Valcik. (1) There are conflicting records of this name; the New York Times gives Walicikoff. In England Opalka was known, of course. So was Valcik, a reliable member of the Prague underground. But what were they doing in the same cellar with Gabcik and Kubis, sharing their hopeless last stand?

Gen Moravec, at least, felt certain that his men would not have violated his orders and made contact with the underground. And no word had gone to the underground about Gabcik and Kubis. (2) In an unpublished manuscript, War Secrets in the Ether, Wilhelm F. Flicke asserts, the attempt upon the life of Heydrich had been planned and directed over the Czech underground to London network. That was a big mistake on the part of the English and Czechs because it afforded the German radio defense a complete disclosure not only of the plot itself and those directly participating but also of all the connections within the Czech resistance movement.

Gen Moravec, at least, felt certain that his men would not have violated his orders and made contact with the underground. And no word had gone to the underground about Gabcik and Kubis. (2) In an unpublished manuscript, War Secrets in the Ether, Wilhelm F. Flicke asserts, the attempt upon the life of Heydrich had been planned and directed over the Czech underground to London network. That was a big mistake on the part of the English and Czechs because it afforded the German radio defense a complete disclosure not only of the plot itself and those directly participating but also of all the connections within the Czech resistance movement.

This statement is almost wholly wrong. It is true that Heydrich and his spies had penetrated the Czech underground thoroughly. But radio was not used for Operation Salmon, and the network inside Czechoslovakia had no hand in planning or directing Heydrich’s assassination. The Germans had no advance warning. And it was not merely an attempt; Gabcik and Kubis did kill Heydrich. Perhaps the two teams had met by chance at the church, driven to the same sanctuary because the priests were known to be patriotic and because all four were desperate. Even now the Nazis went on murdering. The paralytic SS Gen Kurt Daluege succeeded Heydrich. During the trial that preceded his execution in Prague in 1946, he admitted that 1331 Czechs were executed, 201 of them women, in reprisal. From another source it has been established that during this period 3000 Jews were taken from the Terezin ghetto and exterminated. No one knows how many died in concentration camps. A sober estimate is that at least 5000 Czechs were killed to avenge the death of one murderous Nazi. Among them were all the priests of St Bartholomeus, not one of whom would say a word about their guests.