Document Source: OSS FBI File about Operation Pastorius, a failed German intelligence plan for sabotage inside the United States during World War II. The operation was staged in June 1942 and was to be directed against strategic American economic targets. The operation was named by Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, chief of the German Abwehr, for the leader of the first organized settlement of Germans in America. Despite the Quaker sympathies of Francis Daniel Pastorius (1651–1720), his name was appropriated in 1942 by the German Abwehr as the codename of the Operation in the USA known as Operation Pastorius.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, followed by Nazi Germany’s declaration of war on the United States four days later (and the United States’ declaration of war on Germany in response), Hitler authorized a mission to sabotage the American war effort and to make terrorist attacks on civilian targets to demoralize the American civilian population inside the United States. The mission was headed by Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, chief of the German Abwehr. Canaris recalled that during World War I, he organized the sabotage of French installations in Morocco, and entered the United States with other German agents to plant bombs in New York arms factories, including the destruction of munitions supplies at Black Tom Island, in 1916. He hoped that Operation Pastorius would have the same kind of success they had in 1916.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, followed by Nazi Germany’s declaration of war on the United States four days later (and the United States’ declaration of war on Germany in response), Hitler authorized a mission to sabotage the American war effort and to make terrorist attacks on civilian targets to demoralize the American civilian population inside the United States. The mission was headed by Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, chief of the German Abwehr. Canaris recalled that during World War I, he organized the sabotage of French installations in Morocco, and entered the United States with other German agents to plant bombs in New York arms factories, including the destruction of munitions supplies at Black Tom Island, in 1916. He hoped that Operation Pastorius would have the same kind of success they had in 1916.

Recruited for Operation Pastorius were eight German residents who had lived in the United States. Two of them, Ernst Burger and Herbert Haupt, were American citizens. The others, George John Dasch, Edward John Kerling, Richard Quirin, Heinrich Harm Heinck, Hermann Otto Neubauer, and Werner Thiel, had worked at various jobs in the United States. All eight were recruited into the Abwehr military intelligence organization and were given three weeks of intensive sabotage training in the German High Command School on an estate at Quenz Lake, near Berlin, Germany.

Recruited for Operation Pastorius were eight German residents who had lived in the United States. Two of them, Ernst Burger and Herbert Haupt, were American citizens. The others, George John Dasch, Edward John Kerling, Richard Quirin, Heinrich Harm Heinck, Hermann Otto Neubauer, and Werner Thiel, had worked at various jobs in the United States. All eight were recruited into the Abwehr military intelligence organization and were given three weeks of intensive sabotage training in the German High Command School on an estate at Quenz Lake, near Berlin, Germany.

The agents were instructed in the manufacture and use of explosives, incendiaries, primers, and various forms of mechanical, chemical, and electrical delayed timing devices. Considerable time was spent developing complete background ‘histories’ they were to use in the United States. They were encouraged to converse in English and to read American newspapers and magazines so no suspicion would be aroused if they were interrogated while in the United States. Their mission was to stage sabotage attacks on American economic targets: hydroelectric plants at Niagara Falls; the Aluminum Company of America’s plants in Illinois, Tennessee, and New York; locks on the Ohio River near Louisville, Kentucky; the Horseshoe Curve, a crucial railroad pass near Altoona, Pennsylvania, as well as the Pennsylvania Railroad’s repair shops at Altoona; a cryolite plant in Philadelphia; the Hell Gate Bridge in New York; and Pennsylvania Station in Newark, New Jersey.

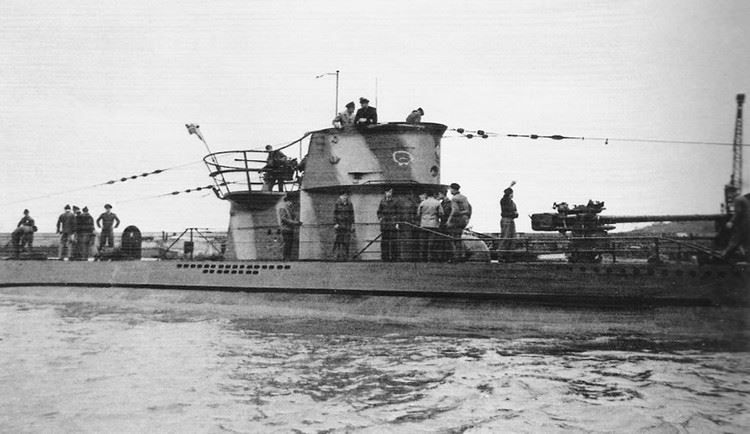

The agents were also instructed to spread a wave of terror by planting explosives on bridges, railroad stations, water facilities, and public places. They were given counterfeit birth certificates, Social Security Cards, draft deferment cards, nearly $175.000 in American money, and driver’s licenses, and put aboard two U-boats to land on the east coast of the US. Before the mission began, it was in danger of being compromised, as George Dasch, head of the team, left sensitive documents behind on a train, and one of the agents when drunk announced to patrons at a bar in Paris, France that he was a secret agent.

During the night of June 12, 1942, the first submarine to arrive in the US, the U-202, landed at Amagansett, New York, which is about 100 miles east of New York City, on Long Island, at what today is Atlantic Avenue beach. It was carrying Dasch and three other saboteurs (Burger, Quirin, and Henck). The team came ashore wearing German Navy uniforms so that if they were captured, they would be classified as prisoners of war rather than spies. They also brought their explosives, primers, and incendiaries, and buried them along with their uniforms. They, then put on civilian clothes to begin an expected two-year campaign the sabotage American defense-related production. After their landing, Dasch was discovered amidst the dunes by an unarmed Coast Guardsman, John C. Cullen.

During the night of June 12, 1942, the first submarine to arrive in the US, the U-202, landed at Amagansett, New York, which is about 100 miles east of New York City, on Long Island, at what today is Atlantic Avenue beach. It was carrying Dasch and three other saboteurs (Burger, Quirin, and Henck). The team came ashore wearing German Navy uniforms so that if they were captured, they would be classified as prisoners of war rather than spies. They also brought their explosives, primers, and incendiaries, and buried them along with their uniforms. They, then put on civilian clothes to begin an expected two-year campaign the sabotage American defense-related production. After their landing, Dasch was discovered amidst the dunes by an unarmed Coast Guardsman, John C. Cullen.

Dasch seized Cullen by the collar, threatened him, and stuffed $ 260 into Cullen’s hand. Cullen reported the encounter to his superiors after returning to his station. By the time an armed Coast Guard patrol returned to the site, the Germans, weary from their trans-Atlantic trip, were gone and had taken the Long Island Rail Road train from the Amagansett Station into Manhattan, New York City, where they checked in and stayed at a hotel. The Coast Guard then discovered German equipment buried in the beach and reported it to the office of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and to the FBI. A massive manhunt for the German agents was conducted; however, they did not know where exactly the Germans were going. The other four-member German team headed by Kerling landed without incident at Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida, south of Jacksonville on June 16, 1942. They came on U-584. This group came ashore wearing bathing suits but wore German Navy hats. After landing ashore, they threw away their hats, put on civilian clothes, and started their mission by boarding trains to Chicago, Illinois, and Cincinnati, Ohio. The two teams were to meet on July 4th in a hotel in Cincinnati to coordinate their sabotage operations.

Dasch seized Cullen by the collar, threatened him, and stuffed $ 260 into Cullen’s hand. Cullen reported the encounter to his superiors after returning to his station. By the time an armed Coast Guard patrol returned to the site, the Germans, weary from their trans-Atlantic trip, were gone and had taken the Long Island Rail Road train from the Amagansett Station into Manhattan, New York City, where they checked in and stayed at a hotel. The Coast Guard then discovered German equipment buried in the beach and reported it to the office of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and to the FBI. A massive manhunt for the German agents was conducted; however, they did not know where exactly the Germans were going. The other four-member German team headed by Kerling landed without incident at Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida, south of Jacksonville on June 16, 1942. They came on U-584. This group came ashore wearing bathing suits but wore German Navy hats. After landing ashore, they threw away their hats, put on civilian clothes, and started their mission by boarding trains to Chicago, Illinois, and Cincinnati, Ohio. The two teams were to meet on July 4th in a hotel in Cincinnati to coordinate their sabotage operations.

(Mission Betrayed) Dasch called Burger into their upper-story hotel room and opened a window, saying they would talk, and if they disagreed, only one of them will walk out that door while the other will fly out the window. Dasch told him he had no intention of going through with the mission, hated Nazism, and planned to report the plot to the FBI. Burger agreed to defect to the United States immediately. On June 15, Dasch phoned the New York Office of the FBI from a pay telephone on Manhattan’s Upper West Side explaining who he was and asked to convey the information to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. When the FBI agent was trying to figure out if he was talking to a crackpot, Dasch hung up. Four days later, he took a train to Washington DC, and checked in at the Mayflower Hotel. Dasch walked into FBI headquarters and asked to speak with Director Hoover. He eventually spoke to Assistant Director D. M. Ladd.

He finally convinced the FBI by dumping his mission’s entire budget of $ 84.000 on the desk of Assistant Director D. M. Ladd. At this point, he was taken seriously and interrogated for hours. Besides Burger, none of the other German agents knew they were betrayed. Over the next two weeks, Burger and the other six were arrested. FBI Chief J. Edgar Hoover made no mention that Dasch had turned himself in, and claimed credit for the FBI for cracking the spy ring.

He finally convinced the FBI by dumping his mission’s entire budget of $ 84.000 on the desk of Assistant Director D. M. Ladd. At this point, he was taken seriously and interrogated for hours. Besides Burger, none of the other German agents knew they were betrayed. Over the next two weeks, Burger and the other six were arrested. FBI Chief J. Edgar Hoover made no mention that Dasch had turned himself in, and claimed credit for the FBI for cracking the spy ring.

(Trial and Execution) Fearful that a civilian court would be too lenient, Roosevelt issued Executive Proclamation 2561 on July 2, 1942, creating a military tribunal to prosecute the Germans. Placed before a seven-member military commission, the Germans were charged with the following offenses: (1) Violating the law of war; (2) Violating Article 81 of the Articles of War, defining the offense of corresponding with or giving intelligence to the enemy; (3) Violating Article 82 of the Articles of War, defining the offense of spying; and (4) Conspiracy to commit the offenses alleged in the first three charges.

The trial was held in Assembly Hall #1 on the fifth floor of the Department of Justice building in Washington DC on July 8, 1942. Lawyers for the accused, who included Lauson Stone and Kenneth Royall, attempted to have the case tried in a civilian court but were rebuffed by the United States Supreme Court in Ex parte Quirin, 317 US 1 (1942), a case that was later cited as a precedent for the trial by military commission of any unlawful combatant against the United States. The trial for the eight defendants ended on August 1, 1942. Two days later, all were found guilty and sentenced to death. Roosevelt commuted Burger’s sentence to life in prison and Dasch’s to 30 years because they had turned themselves in and provided information about the others. The others were executed on August 8, 1942, on the electric chair on the third floor of the District of Columbia jail and buried in a potter’s field in the Blue Plains neighborhood in the Anacostia area of Washington.

The trial was held in Assembly Hall #1 on the fifth floor of the Department of Justice building in Washington DC on July 8, 1942. Lawyers for the accused, who included Lauson Stone and Kenneth Royall, attempted to have the case tried in a civilian court but were rebuffed by the United States Supreme Court in Ex parte Quirin, 317 US 1 (1942), a case that was later cited as a precedent for the trial by military commission of any unlawful combatant against the United States. The trial for the eight defendants ended on August 1, 1942. Two days later, all were found guilty and sentenced to death. Roosevelt commuted Burger’s sentence to life in prison and Dasch’s to 30 years because they had turned themselves in and provided information about the others. The others were executed on August 8, 1942, on the electric chair on the third floor of the District of Columbia jail and buried in a potter’s field in the Blue Plains neighborhood in the Anacostia area of Washington.

(Aftermath) The failure of Operation Pastorius led Hitler to rebuke Admiral Canaris and no sabotage attempt was ever made again in the United States. During the remaining years of the war, the Germans only once more dispatched agents to the United States by submarine. In November 1944, as part of Operation Elster, a German submarine, the U-1230, dropped two RSHA spies off the coast of Maine to gather intelligence on American manufacturing and technical progress. The FBI captured both men shortly after.

These agents benefited from the calmer state of public nerves in the later years of the war and received prison sentences rather than execution. In 1948, President Harry S. Truman granted executive clemency to Dasch and Burger on the condition that they are deported to the American Zone of occupied Germany. They were not welcomed back in Germany, as they were regarded as traitors who had caused the death of their comrades. Although they had been promised pardons by Hoover in exchange for their cooperation, both men died without ever receiving them. Dasch died in 1992 at the age of 89 in Ludwigshafen, Germany. Burger died in 1975.

These agents benefited from the calmer state of public nerves in the later years of the war and received prison sentences rather than execution. In 1948, President Harry S. Truman granted executive clemency to Dasch and Burger on the condition that they are deported to the American Zone of occupied Germany. They were not welcomed back in Germany, as they were regarded as traitors who had caused the death of their comrades. Although they had been promised pardons by Hoover in exchange for their cooperation, both men died without ever receiving them. Dasch died in 1992 at the age of 89 in Ludwigshafen, Germany. Burger died in 1975.

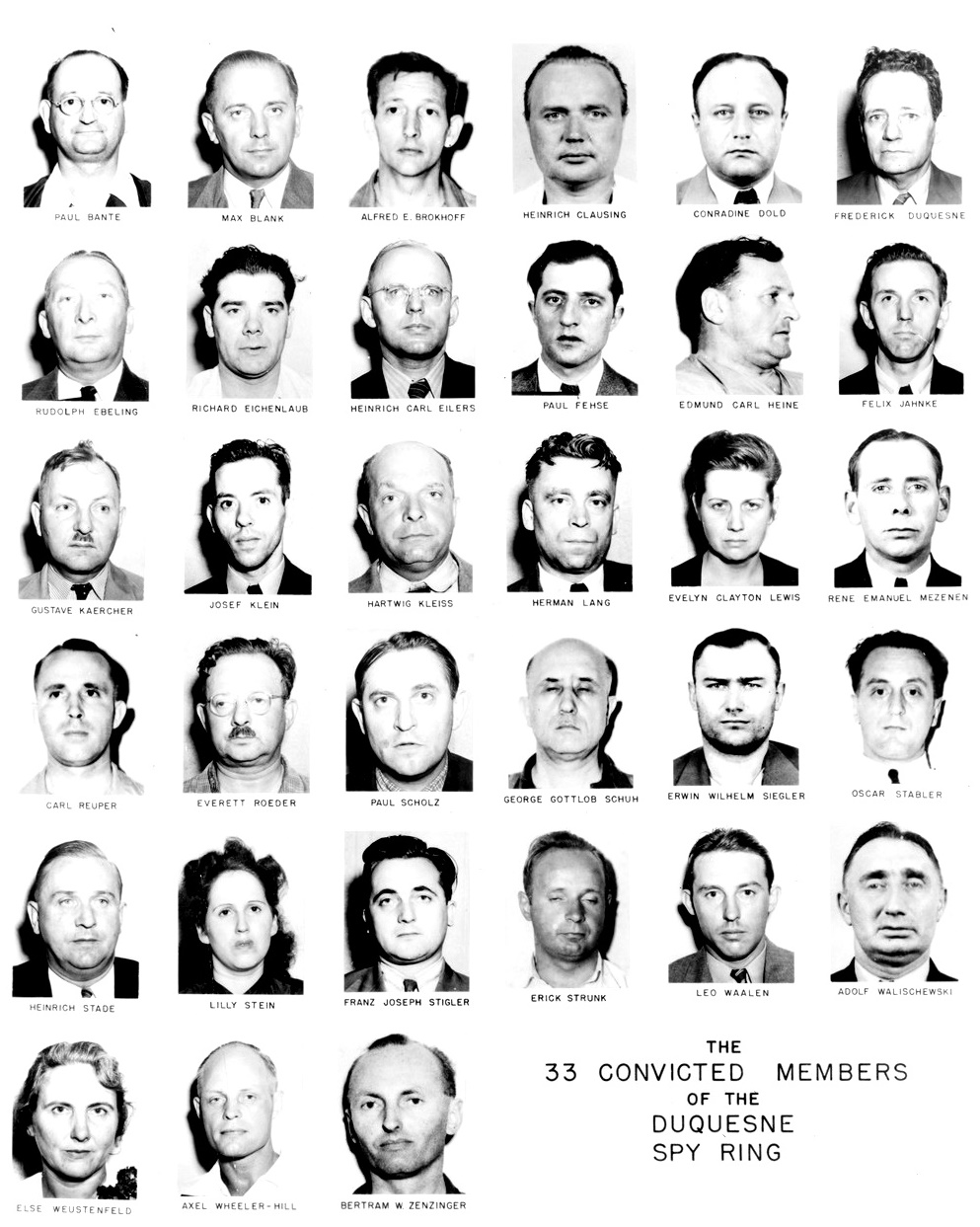

The Duquesne Spy Ring is the largest espionage case in United States history that ended in convictions. A total of 33 members of a German espionage network headed by Frederick ‘Fritz’ Joubert Duquesne were convicted after a lengthy investigation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Of those indicted, 19 pleaded guilty. The remaining 14 were brought to a jury trial in Federal District Court, Brooklyn, New York, on September 3, 1941, and all were found guilty on December 13, 1941. On January 2, 1942, the group was sentenced to serve a total of over 300 years in prison.

The agents who formed the Duquesne Ring were placed in key jobs in the United States to get information that could be used in the event of war and to carry out acts of sabotage. One opened a restaurant and used his position to get information from his customers; another worked on an airline so that he could report Allied ships that were crossing the Atlantic Ocean while others, worked as delivery people as a cover for carrying secret messages. William G. Sebold, who had been blackmailed into becoming a spy for Germany, became a double agent and helped the FBI gather evidence. For nearly two years, the FBI ran a shortwave radio station in New York for the ring. They learned what information Germany was sending its spies in the United States and controlled what was sent to Germany. Sebold’s success as a counterespionage agent was demonstrated by the successful prosecution of the German agents. One German spymaster later commented the ring’s roundup delivered the death blow to their espionage efforts in the United States. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover called his concerted FBI to swoop on Duquesne’s ring the greatest spy roundup in US history.

The agents who formed the Duquesne Ring were placed in key jobs in the United States to get information that could be used in the event of war and to carry out acts of sabotage. One opened a restaurant and used his position to get information from his customers; another worked on an airline so that he could report Allied ships that were crossing the Atlantic Ocean while others, worked as delivery people as a cover for carrying secret messages. William G. Sebold, who had been blackmailed into becoming a spy for Germany, became a double agent and helped the FBI gather evidence. For nearly two years, the FBI ran a shortwave radio station in New York for the ring. They learned what information Germany was sending its spies in the United States and controlled what was sent to Germany. Sebold’s success as a counterespionage agent was demonstrated by the successful prosecution of the German agents. One German spymaster later commented the ring’s roundup delivered the death blow to their espionage efforts in the United States. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover called his concerted FBI to swoop on Duquesne’s ring the greatest spy roundup in US history.

On January 2, 1942, 33 members of a Nazi spy ring headed by Frederick Joubert Duquesne were sentenced to serve a total of over 300 years in prison. They were brought to justice after a lengthy espionage investigation by the FBI. William Sebold, who had been recruited as a spy for Germany, was a major factor in the FBI’s successful resolution of this case through his work as a double agent for the United States. A native of Germany, William Sebold served in the German army during World War I. After leaving Germany in 1921, he worked in industrial and aircraft plants throughout the United States and South America. On February 10, 1936, he became a naturalized citizen of the United States. Sebold returned to Germany in February 1939, to visit his mother in Mulheim. Upon his arrival in Hamburg, Germany, he was approached by a member of the Gestapo who said that Sebold would be contacted in the near future. Sebold proceeded to Mulheim where he obtained employment.

In September 1939, a man named Dr. Gassner visited Sebold in Mulheim and interrogated him regarding military planes and equipment in the United States. He also asked Sebold to return to the United States as an espionage agent for Germany. Subsequent visits by Dr. Gassner and another man named Dr. Renken, later identified as Maj Nickolaus Ritter of the German Secret Service, persuaded Sebold to cooperate with the Reich because he feared reprisals against family members still living in Germany. Since Sebold’s passport had been stolen shortly after his first visit from Dr. Gassner, Sebold went to the American Consulate, in Cologne, Germany, to obtain a new one.

While doing so, Sebold secretly told the personnel of the American Consulate about his future role as a German agent and expressed his wish to cooperate with the FBI upon his return to America. Sebold reported to Hamburg, Germany, where he was instructed to prepare coded messages and micro-photographs. Upon completion of training, he was given five micro-photographs containing instructions for preparing a secret code and detailing the type of information he was to transmit to Germany from the United States. Sebold was told to retain two of the micro-photographs and to deliver the other three to German operatives in the United States.

While doing so, Sebold secretly told the personnel of the American Consulate about his future role as a German agent and expressed his wish to cooperate with the FBI upon his return to America. Sebold reported to Hamburg, Germany, where he was instructed to prepare coded messages and micro-photographs. Upon completion of training, he was given five micro-photographs containing instructions for preparing a secret code and detailing the type of information he was to transmit to Germany from the United States. Sebold was told to retain two of the micro-photographs and to deliver the other three to German operatives in the United States.

After receiving final instructions, including using the assumed name of Harry Sawyer, he sailed from Genoa, Italy, and arrived in New York City on February 8, 1940. The FBI previously had been advised of Sebold’s expected arrival, his mission, and his intentions to assist them in identifying German agents in the United States. Under the guidance of Special Agents, Sebold established residence in New York City as Harry Sawyer. Also, an office was established for him as a consultant diesel engineer, to be used as a cover in establishing contacts with members of the spy ring. In selecting this office for Sebold, the FBI Agents ensured that they could observe any meetings taking place there. In May 1940, a shortwave radio transmitting station operated by FBI Agents on Long Island established contact with the German shortwave station abroad. This radio station served as the main channel of communication between German spies in New York City and their superiors in Germany for 16 months. During this time, the FBI’s radio station transmitted over 300 messages to Germany and received 200 messages from Germany. Sebold’s success as a counterespionage agent against Nazi spies in the United States is demonstrated by the successful prosecution of the 33 German agents in New York. Of those arrested on charges of espionage, 19 pleaded guilty. The 14 men who entered pleas of riot guilty were brought to trial in Federal District Court, Brooklyn, in New York on September 3, 1941, and they were all found guilty by a jury on December 13, 1941. The activities of each of these convicted spies and Sebold’s role in uncovering their espionage activities for the Reich follow.

Frederick Fritz Joubert Duquesne

Frederick Fritz Joubert Duquesne

Born in Cape Colony, South Africa, on September 21, 1877, Duquesne emigrated from Hamilton, Bermuda, to the United States in 1902 and became a naturalized United States citizen on December 4, 1913. Duquesne was implicated in fraudulent insurance claims, including one that resulted from a fire aboard the British steamship Tennyson’ which caused the vessel to sink on February 18, 1916. When Duquesne was arrested on November 17, 1917, he had in his possession a large file of news clippings concerning bomb explosions on ships and a letter from the Assistant German Vice Consul at Managua, Nicaragua. The letter indicated that Capt Duquesne was one who has rendered considerable service to the German cause. When Sebold returned to the United States in January 1942, Duquesne was operating a business known as the Air Terminals Company in New York City. After establishing his first contact with Duquesne by letter, Sebold met with him in Duquesne’s office.

During their initial meeting, Duquesne, who was extremely concerned about the possibility of electronic surveillance devices being present in his office, gave Sebold a note stating that they should talk elsewhere. After relocating to an Automat, the two men exchanged information about members of the German espionage system with whom they had been in contact.

During their initial meeting, Duquesne, who was extremely concerned about the possibility of electronic surveillance devices being present in his office, gave Sebold a note stating that they should talk elsewhere. After relocating to an Automat, the two men exchanged information about members of the German espionage system with whom they had been in contact.

Duquesne provided Sebold with information for transmittal to Germany during subsequent meetings, and the meetings which occurred in Sebold’s office were filmed by FBI Agents. Duquesne, vehemently anti-British, submitted information dealing with national defense in America, the sailing of ships to British Ports and technology. He also regularly received money from Germany in payment for his services. On one occasion, Duquesne provided Sebold with photographs and specifications of a new type of bomb being produced in the United States. He claimed that he secured that material by secretly entering tire DuPont plant in Wilmington, Delaware.  Duquesne also explained how fires could be started in industrial plants. Much of the information Duquesne obtained was the result of his correspondence with industrial concerns. Representing himself as a student, he requested data concerning their products and manufacturing conditions. Duquesne was brought to trial and was convicted. He was sentenced to serve 18 years in prison on espionage charges, as well as a 2-year concurrent sentence and payment of a $2000 fine for violation of the Registration Act.

Duquesne also explained how fires could be started in industrial plants. Much of the information Duquesne obtained was the result of his correspondence with industrial concerns. Representing himself as a student, he requested data concerning their products and manufacturing conditions. Duquesne was brought to trial and was convicted. He was sentenced to serve 18 years in prison on espionage charges, as well as a 2-year concurrent sentence and payment of a $2000 fine for violation of the Registration Act.

A native of Germany, Paul Bante served in the German army during WW-1. He came to the United States in 1930 and became a naturalized United States citizen in 1938. Bante, formerly a member of the German-American Bund, claimed that Germany put him in contact with one of their operatives, Paul Fehse, because of Bante’s previous, association with someone named Dr. Ignatz T. Griebl. Before fleeing to Germany to escape prosecution, Dr. Griebl had been implicated in a Nazi spy ring with Guenther Gustave Rumrich, who was tried on espionage charges in 1938. Bante assisted Paul Fehse in obtaining information about ships bound for Britain with war materials and supplies. Bante claimed that as a member of the Gestapo, his function was to create discontent among union workers, stating that every strike would assist Germany. Sebold met Bante at the Little Casino Restaurant, which was frequented by several members of this spy ring. During one such meeting, Bante advised that he was preparing a fuse bomb, and he subsequently delivered dynamite and detonation caps to Sebold. Entering a guilty plea to a violation of the Registration Act, Bante was sentenced to 18 months imprisonment and was fined $1000.

Max Blank came to the United States from Germany in 1928. Although he never became a United States citizen, Blank had been employed in New York City at a German library and at a bookstore that catered to German trade. Paul Fehse, a major figure, in this case, informed Germany that Blank, who was acquainted with several members of the spy ring, could secure some valuable information but lacked the funds to do so. Later Fehse and Blank met with Sebold in his office. They told Sebold that Blank could obtain details about rubberized self-sealing airplane gasoline tanks, as well as a sew braking device for airplanes, from a friend who worked in a shipyard. However, he needed money to get the information. Blank pleaded guilty to violation of the Registration Act. He received a sentence of 18 months imprisonment and a $1000 fine.

Native of Germany, Alfred E. Brokhoff came to the United States in 1923 and became a naturalized citizen in 1929. He was a mechanic for the United States Lines in New York City for 17 years prior to his arrest. Because of his employment on the docks, he knew almost all of the other agents in this group who were working as seamen on various ships. Brokhoff helped Fehse secure information about the sailing dates and cargoes of vessels destined for England. He also assisted Fehse in transmitting this information to Germany. Also, another German agent, George V. Leo Waalen, reported that he had received information from Brokhoff for transmittal to Germany. Upon conviction, Brokhoff was sentenced to serve a five-year prison term for violation of the espionage statutes and to serve a two-year concurrent sentence for violation of the Registration Act.

In September 1934, German-born Heinrich Clausing came to the United States, where he became a naturalized citizen in 1938. Having served on various ships sailing from New York Harbor since his arrival in the country, he was employed as a cook on the USS Argentine at the time of his arrest. Closely associated with Franz Stigler, one of the principal contact men for this spy ring. Clausing operated as a courier. He transported microphotographs and other material from the United States to South American ports, from which the information was sent to Germany via Italian airlines. He also established a mail drop in South America for the expeditious transmittal of information to Germany by mail. Claising was convicted and was sentenced to serve eight years for violation of the espionage statutes. He also received a two years concurrent sentence for violation of the Registration Act.