Document Source: Operation of the 37th Infantry Division in the crossing of the Pasig River and the closing to the Walls of Intramuros, Manila, February 7-9, 1945 during the Luzon Campaign. Maj Giles H. Kidd, Infantry.

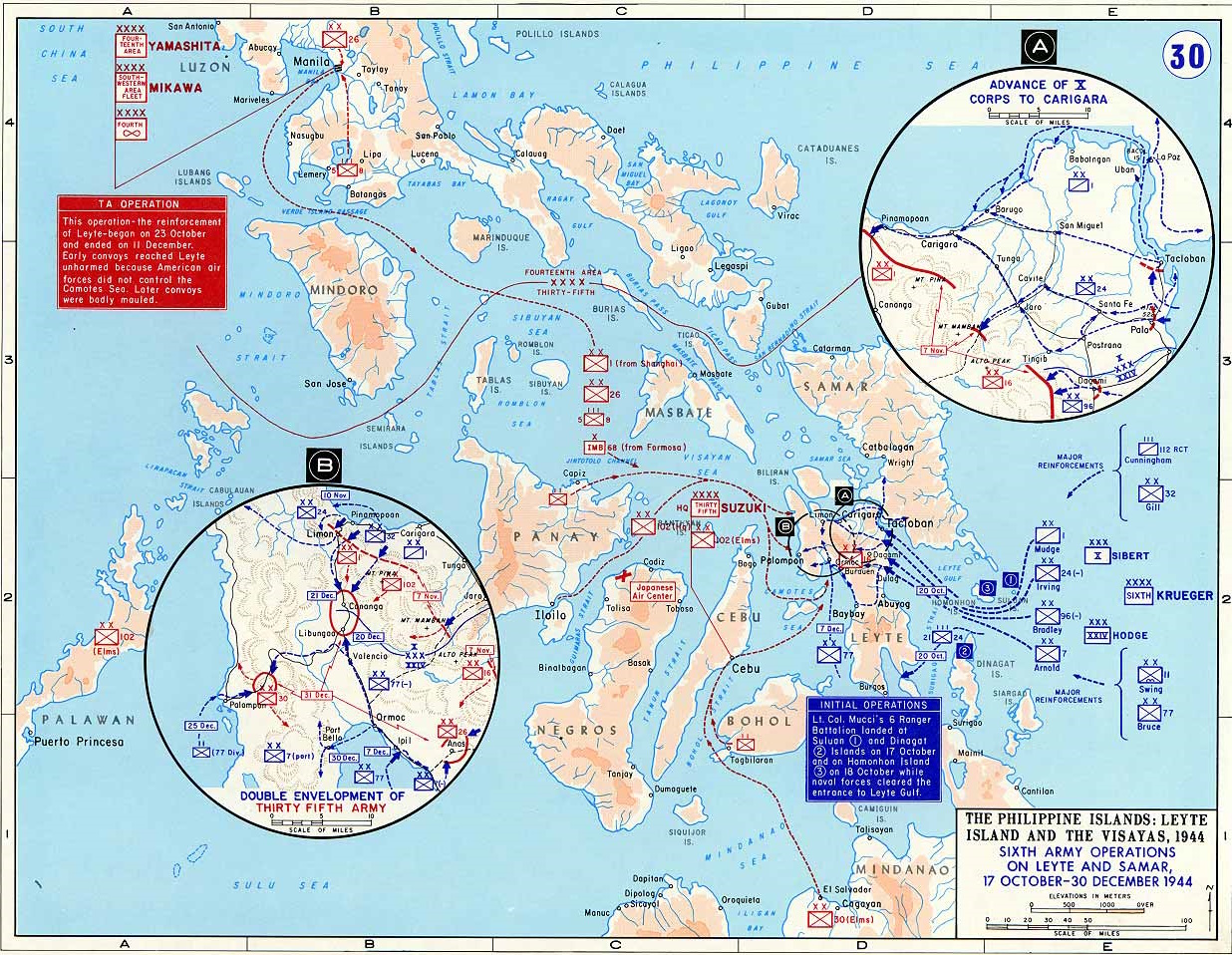

This archive covers the operations of the 37th Infantry Division in the crossing of the Pasig River and the closing to the Walls of Intramuros, Manila during the period February 7, 1945 – February 9, 1945. In order to orient the reader, it will be necessary to discuss briefly the major planning phases of various levels of command leading to the actual execution of the operation. Most of us recall the fall of the Philippines which started with an intense air bombardment by the Japanese on December 8, 1941. This and subsequent enemy gains in the Philippines resulted in Gen Douglas MacArthur receiving an order from the President of the United States to leave Corregidor in order to establish and assume command of the General Headquarters in Australia. This outstanding leader departing with his small group via Patrol Torpedo (PT) boat made the now famous statement, ‘I shall return’. In June 1944, the General Headquarters Southwest Pacific Area announced a very broad plan designed to liberate the Philippines just when the US Sixth Army was about to gain control of the northern coast of  New Guinea. On September 30, 1944, the Headquarters US Sixth Army received a staff study from the GHQ, of the plans for the Luzon Campaign. On October 12, 1944, the GHQ announced that the Sixth Army would be the force that would make the initial landings on the Island of Luzon in the Philippine Group. This directive came Just in the middle of preparations for the movement to Leyte.

New Guinea. On September 30, 1944, the Headquarters US Sixth Army received a staff study from the GHQ, of the plans for the Luzon Campaign. On October 12, 1944, the GHQ announced that the Sixth Army would be the force that would make the initial landings on the Island of Luzon in the Philippine Group. This directive came Just in the middle of preparations for the movement to Leyte.

US SIXTH ARMY PLAN

Early in November 1944, on the order of the GHQ, the Sixth Army Commander submitted his plan, based on the concept previously set forth by the Commander-in-Chief of the Southwest Pacific Area area for the Sixth Army participation in the Luzon Campaign. The features of this plan were divided into the three following phases: Phase I – An amphibious operation to seize beachheads in the Lingayen-Damortis area of the Lingayen Gulf; Phase II – To attack and destroy all enemy forces north of the Agno River and to seize and hold crossings over the Agno River; Phase III – The destruction of hostile forces in the Central Plain Area and the continuation of the attack to capture Manila. The major combat units assigned to the Sixth Army for the Luzon Campaign were: Headquarters I Corps; Headquarters XIV Corps; 6th Infantry Division; 11th Airborne Division; 13th Armored Group; 25th Infantry Division; 37th Infantry Division; 40th Infantry Division; 43rd Infantry Division; 158th Infantry Regiment (Bushmasters).

THE XIV CORPS PLAN

The XIV Corps planned to land amphibiously two divisions abreast in the Lingayen Area of the Lingayen Gulf, the 37th Infantry Division- on the left and east of the 40th Infantry Division. Each division was to have a landing beach of approximately 2000 yards. The objective for S-Day (January 9), was to seize ground running generally east to west from Dagupan to crossings

The XIV Corps planned to land amphibiously two divisions abreast in the Lingayen Area of the Lingayen Gulf, the 37th Infantry Division- on the left and east of the 40th Infantry Division. Each division was to have a landing beach of approximately 2000 yards. The objective for S-Day (January 9), was to seize ground running generally east to west from Dagupan to crossings

along the Calamay River and the Agno River within the Corps zone. All units were to push vigorously to the south; the 40-ID to protect the right flank of the Sixth Army and the 37-ID to maintain contact with the I Corps, on the left, thus accomplishing phase one.

along the Calamay River and the Agno River within the Corps zone. All units were to push vigorously to the south; the 40-ID to protect the right flank of the Sixth Army and the 37-ID to maintain contact with the I Corps, on the left, thus accomplishing phase one.

The second phase of the Corps plan called for the 37-ID to push through the Central Plain of Luzon, to the south and the 40-ID down the west coast of Luzon and clear the Clark Field – Stotsenburg Area of all hostile forces. The third phase of the Corps plan called for the 40-ID to clear and secure the rugged Zambeles Mountains to the west of the Fort Stotsenburg Area. The 37-ID was to seize the line Malolos – Sibul – Springs – Cabamatuan and be prepared to advance promptly to Manila on order.

ENEMY LOCATIONS AND STRENGTHS

Enemy strength on the island of Luzon at the time of the landing at Lingayen Gulf was estimated by various commands as 150.000 minimum to a maximum of 235.000 Japanese troops. The disposition of enemy forces on Luzon was broken down more concisely as follows: Northern Luzon, 37.500 men of which 23.000 were combat troops; Central Luzon, 77.000 men of which 47.000 were combat troops; Batangas Area, 31.000 troops of which 21.000 were combat troops, and Bicol Peninsula, 15.500 troops.

37TH INFANTRY DIVISION SITUATION

During the night of January 8/9, the convoys carrying the XIV and I Corps entered the Lingayen Gulf. The convoys were supported by the US Navy Third Fleet and the US Navy Seventh Fleet, and the Fourteenth and Twentieth Air Forces of the US Army Air Forces. The 148th Infantry Regiment on the right (west) of the division zone with two battalions abreast had the mission of advancing inland to the left along the beach to Dagupan. Support by tanks, tank destroyers, and artillery

During the night of January 8/9, the convoys carrying the XIV and I Corps entered the Lingayen Gulf. The convoys were supported by the US Navy Third Fleet and the US Navy Seventh Fleet, and the Fourteenth and Twentieth Air Forces of the US Army Air Forces. The 148th Infantry Regiment on the right (west) of the division zone with two battalions abreast had the mission of advancing inland to the left along the beach to Dagupan. Support by tanks, tank destroyers, and artillery

was available, and support by naval gunfire and arid air would be available on call. Progress was rapid and contact was made with the 40-ID on the right immediately, but contact was not made with I Corps (on the left) until S+2 (January 11). The 129th Infantry advanced immediately southeast to the village of Dagupan and crossed the Dagupan River where a perimeter defense was set up for the night of January 9. Using the Lupis – Binmaley highway as an axis of advance, the 148th Infantry advanced to the Calmay River on S-Day. The 145th Infantry was in Corps reserve until January 10, busily engaged in the unloading of LSTs and repairing the Lingayen Airfield. All bridges across both the Dugapan River and the Calmay River within the division zone had been destroyed. Destruction of these bridges represented a small portion of the fifty-one highway bridges that were destroyed by the retreating Japanese between the Lingayen Gul and Manila. The bridge situation severely hampered the division’s progress. Although foot troops could usually wade across the streams and rivers, heavy vehicle traffic was impossible for as long as three days at a time. The reason for this is that the Bailey Bridges, although available for the purpose, were scattered over several ships and arrived piecemeal, making them very hard to find and assemble.

was available, and support by naval gunfire and arid air would be available on call. Progress was rapid and contact was made with the 40-ID on the right immediately, but contact was not made with I Corps (on the left) until S+2 (January 11). The 129th Infantry advanced immediately southeast to the village of Dagupan and crossed the Dagupan River where a perimeter defense was set up for the night of January 9. Using the Lupis – Binmaley highway as an axis of advance, the 148th Infantry advanced to the Calmay River on S-Day. The 145th Infantry was in Corps reserve until January 10, busily engaged in the unloading of LSTs and repairing the Lingayen Airfield. All bridges across both the Dugapan River and the Calmay River within the division zone had been destroyed. Destruction of these bridges represented a small portion of the fifty-one highway bridges that were destroyed by the retreating Japanese between the Lingayen Gul and Manila. The bridge situation severely hampered the division’s progress. Although foot troops could usually wade across the streams and rivers, heavy vehicle traffic was impossible for as long as three days at a time. The reason for this is that the Bailey Bridges, although available for the purpose, were scattered over several ships and arrived piecemeal, making them very hard to find and assemble.

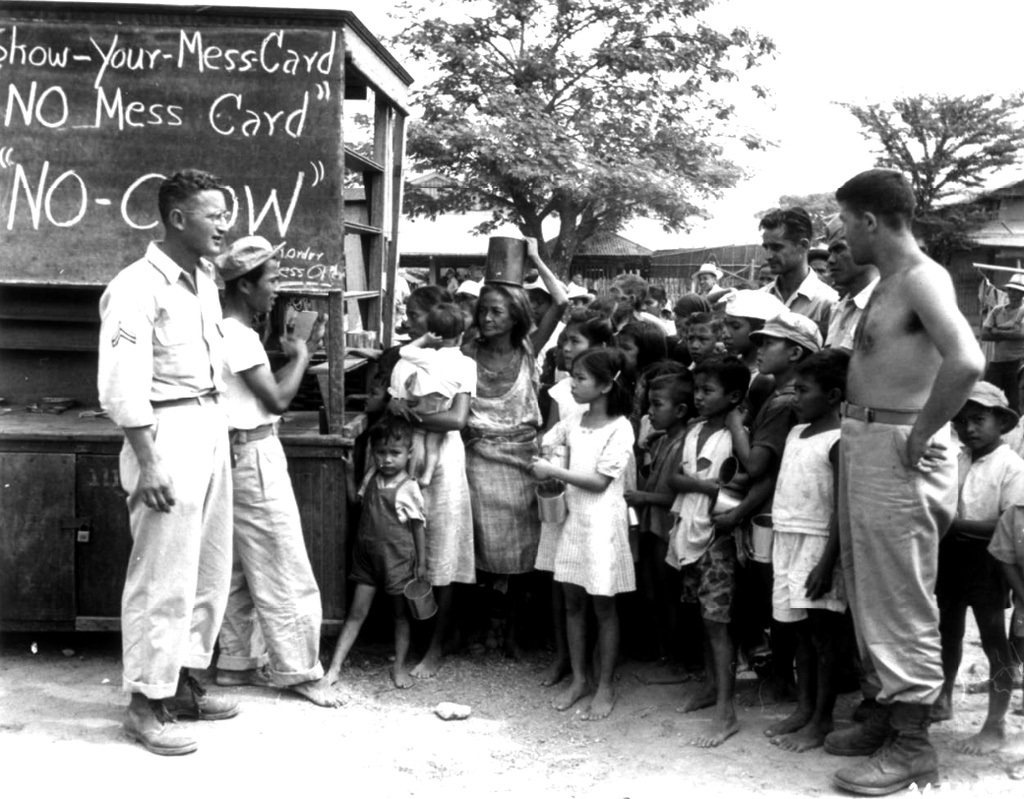

Shortly after the landing, the division was faced with many civilian problems which continued to exist throughout the entire operation. Often violent demonstrations would break out between various political and guerrilla factions. Civilians began to ‘flock’ into medical installations for food, shelter, and much-needed medical care. Having to take care of this situation from the time of the landing of the division and throughout the entire campaign, medical personnel was subjected to severe strain and medical services to troops were seriously impeded.

The assault regiments spent the next three days (until January 16) establishing and securing the army beachhead line. On January 16, the assault regiments started moving south on Corps order to occupy the Agno River line and outpost the Camiling – Paniqui Line. The advance thus far had met very little enemy resistance. From January 16 to January 24, the division moved generally south by bounds cleaning out small pockets of enemy resistance along the way. On January 25, the division received a Corps warning order to advance south, seize and secure the line Fort Stostsenburg – Angeles – Malagan. It now appeared that the rapid advance of the XIV Corps was at an end as the I Corps on the left had encountered bitter enemy resistance; therefore, an exposed flank of about fifty-three miles existed on the east. The division had advanced almost seventy miles and held a front of forty-seven miles in the first seventeen days of the campaign.

At the same time, the 40-ID, on the right, was meeting stubborn resistance in the little town of Bamban to the northeast of Fort Stotsenburg. Rather than continue the advance to the south with the 37-ID and take a chance of a strong enemy counterattack against the 40-ID from the west, which if successful would cut the main supply line, the corps commander decided to leave one reinforced RCT of the 37-ID to protect the left flank, and hurl the remainder of his forces against the strong enemy positions in the Clark Field – Fort Stotsenburg Area. On January 26, the 37-ID launched an attack to the west on the Clar Field – Stotsenburg Area in conjunction with the 40-ID, with the 129th Infantry Regiment on the right and the 145th Regimental Combat Team on the left. Other than sporadic small-arms fire movement was rapid. By moving west, the 37-ID soon drew abreast of the 40-ID on the right, which had launched its attack the same day in the hills northwest of Clark Field in the vicinity of Bamban. Although the Japs defended every yard stubbornly, they were unable to stop the attack. On January 31, the largest airfield in the Philippines, Clark Field, was in American hands. The enemy, however, continued to resist bitterly in his mountain defenses west of Fort Stotsenburg.

The primary mission of the XIV Corps being to advance to the south and capture Manila, the corps commander issued orders directing the attachment of one regiment of the 37-ID to the 40-ID to assist in the clearing of the Japanese mountain defenses west of Clarg Field and Fort Stotsenburg as the security of the area hinged on driving the enemy deeper into the western mountains. The 37-ID was to continue its advance to the south. On January 27, the 1st Cavalry Division landed on the beach in the Lingayen Gulf. Based on the fact that the I Corps was well occupied to the north as well as to the east of the 37-ID, some fifty miles back, and that the enemy showed signs of disorganization, the 1st Cavalry Division was placed under XIV Corps control and ordered to move with all possible speed south on the 37-ID’s left flank toward Manila.

The primary mission of the XIV Corps being to advance to the south and capture Manila, the corps commander issued orders directing the attachment of one regiment of the 37-ID to the 40-ID to assist in the clearing of the Japanese mountain defenses west of Clarg Field and Fort Stotsenburg as the security of the area hinged on driving the enemy deeper into the western mountains. The 37-ID was to continue its advance to the south. On January 27, the 1st Cavalry Division landed on the beach in the Lingayen Gulf. Based on the fact that the I Corps was well occupied to the north as well as to the east of the 37-ID, some fifty miles back, and that the enemy showed signs of disorganization, the 1st Cavalry Division was placed under XIV Corps control and ordered to move with all possible speed south on the 37-ID’s left flank toward Manila.

From January 27 to January 31, inclusive, the 37-ID units that had been engaged in the Clark Field and Fort Sotsenburg action were busy clearing out small pockets of resistance to the west and securing the area which they had taken from the enemy. On February 1, the 148-IR moved back into the southeast abreast of the 145-IR to continue the advance to the south along the original axis of attack (Highway 3) and toward Manila. This advance was impeded by the necessity of constructing bridges at every water course; mainly the wide Pampanga River at Calumpit. Although foot troops, jeeps, and a minimum of supplies were transported across the river by amphibious tractors the bulk of the division loads were stalemated until the completion of a pontoon bridge by the engineers. Here again, as many times before, the engineers ran into supply difficulties as sixty feet of the bridge decking material was missing.

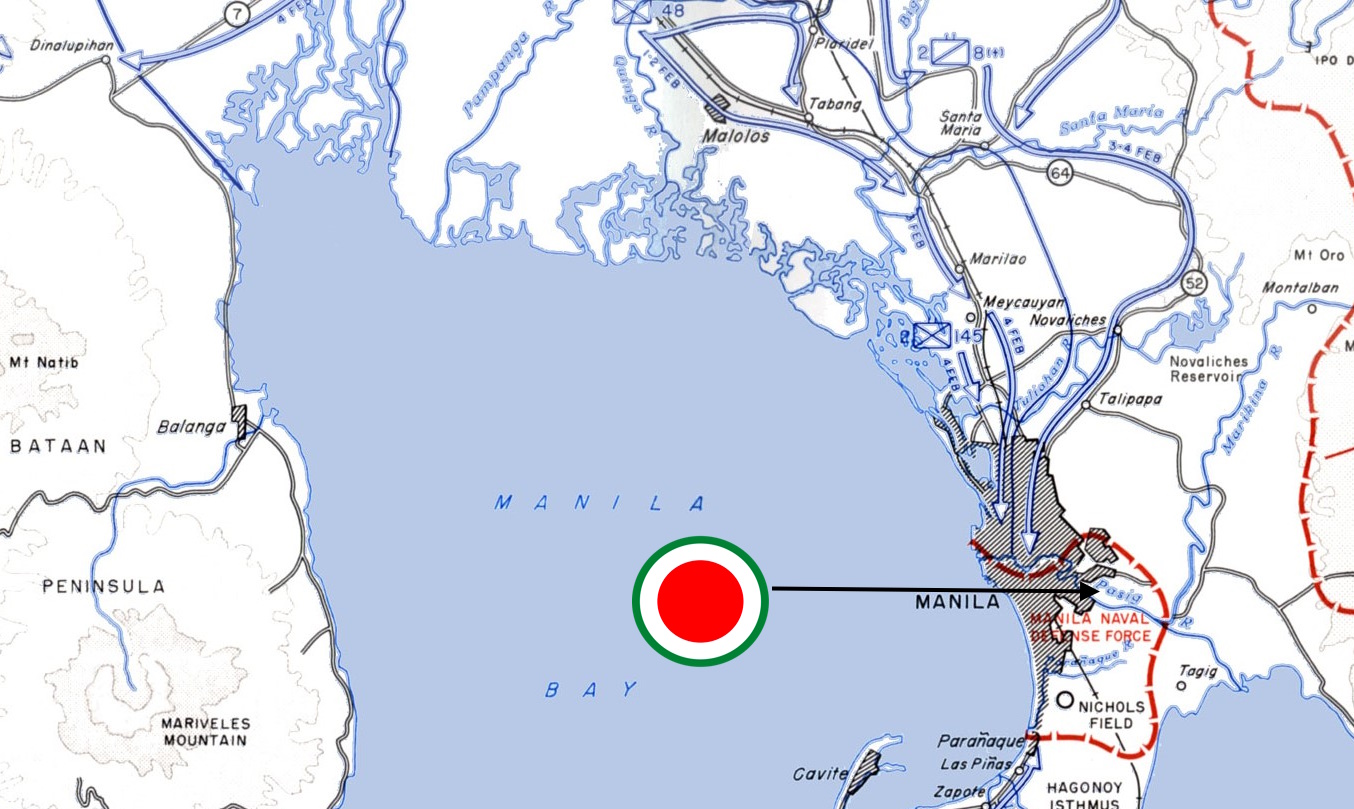

On February 2, the 129-IR which had been attached to the 40-ID at Fort Stotsenburg was released from attachment and immediately began its advance south toward Manila to join the division. Both, the 145-IR and the 148-IR continued southward on Highways 3 and 51 on February 3 and 4. During this movement and up until the division reached the north bank of the Pasig River on February 7, the two regiments met continuous enemy artillery barrages, small arms fire, and definite strong centers of resistance. Due to falling debris and difficult stream crossings, the division was unable to reinforce the infantry units with armor.