Document source: The 101st Airborne Division’s Defense of Bastogne, Col Ralph M. Mitchell, September 1986, US Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

I. BASTOGNE: THE CONTEXT OF THE BATTLE

I. BASTOGNE: THE CONTEXT OF THE BATTLE

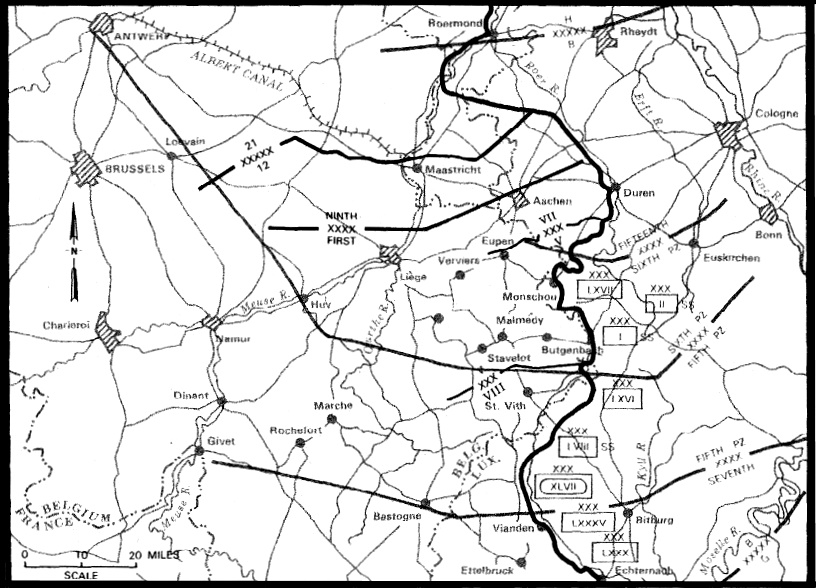

By October 1944, the rapid Allied advance into Germany that followed the breakout from the Normandy beaches had slowed to a crawl. Stiffening German resistance and Allied logistical and communications problems exerted a significant influence on the Allied advance. In the American sector, Gen Omar N. Bradley’s 12th Army Group occupied an extended front, with the US 1-A (Hodges) and the US 3-A (Patton) along the Siegfried Line and the US 9-A (Simpson) facing the Roer River. There would be little change in these positions in October and November 1944.

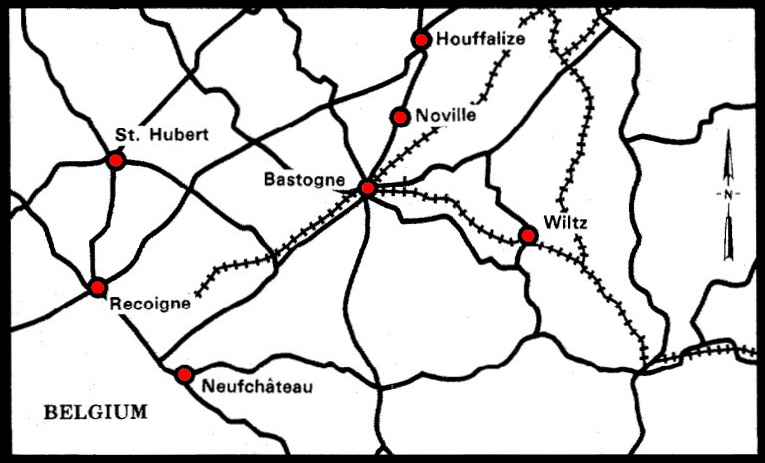

The US 1-A had an extensive line of defense near Aachen, Germany. Gen Troy H. Middleton’s VIII Corps occupied that army’s southern sector. Its 88-mile front extended from Losheim, Germany, north through eastern Belgium and Luxembourg to where the Our River crosses the France-German border. The corps’ mission was to defend in place in a relatively quiet sector. There, new divisions could receive a safe indoctrination, and battle-weary ones could rest and reconstitute for future operations. The Headquarters of the US VIII Corps was located in the small Belgian town of Bastogne. The area around Bastogne was characterized by rugged hills, high plateaux, deep-cut valleys, and restricted road nets. Bastogne itself was the hub for seven roads and a railroad. Both sides understood the significance of that fact.

Alarmed by the continuing grave situation in the east, Adolph Hitler saw an opportunity for a decisive offensive in the west as the Allied offensive stalled there. Without complete support from his closest advisers, he directed the launching of a winter offensive against the western Allies through the Aisne-Ardennes sector of the front. The purpose was to recapture the important port of Antwerp while encircling and destroying the British 21-AG. In so doing, Hitler would turn the fate of the war in Germany’s favor. Middleton’s VIII Corps, however, was directly astride the main avenue of the advance of the 5.Panzer-Army (Manteuffel).

Few German officers were privy to the plans for this offensive, called Watch on Rhine. Most Germans thought preparations were for defensive measures until a few days before the attack began. Operating with little insight as to the ultimate objectives of their own units, many commanders had an insufficient opportunity for reconnaissance and failed to consider the numerous contingencies that might soon arise. They remained unaware of the tactical implications of their situations, while Hitler’s intuition was allowed to prevail.

The Germans, however, had identified Bastogne as a possible point of major difficulty and had considered the control of the vital crossroads through that town to be absolutely necessary to maintain their rear area lines of communication. The German Führer, Adolf Hitler, had expressly ordered the capture of the city Bastogne, and that mission had been passed through Army Group (Heeresgruppe) and 5.Panzer-Army to XLVII.Panzer-Corps, which would be attacking through the Bastogne sector. Specifically, the corps was to cross the Our River on a wide front, bypass the Clerf sector, take Bastogne, and move to and cross the Meuse River south of Namur.

The corps’ commander, Gen Heinrich von Luettwitz, had specifically asked about Bastogne at a conference in Kyllburg prior to the offensive. In the presence of Gen von Manteuffel, 5.Panzer-Army commander, von Luettwitz was told that Bastogne would definitely have to be taken. Accordingly, in instructions to his subordinates, he stated: Bastogne must be captured, if necessary from the rear. Otherwise, it will be an abscess in the route of advance and tie up too many forces. Bastogne is to be mopped up first, then the bulk of the corps continues its advance.

In light of such specific guidance prior to the operation, it is curious that the 5.Panzer-Army staff did not interpret those instructions the same way. Chief of Staff, Gen Carl Wagener, stated, Bastogne would not necessarily have to be taken but merely encircled. This would avoid any loss of time east of the Meuse. The Germans expected that the advance to the Meuse would not be delayed by any attack on Bastogne because both would be accomplished simultaneously. Luettwitz also differed with 5.Panzer-Army about the amount of time it would take his men to reach the Meuse. The 5.Panzer-Army’s staff expected the attack to take four days; the commander of XLVII Panzer-Corps thought it would take six days and had doubts about taking Bastogne by the end of the second day as the 5.Panzer-Army had projected. Luettwitz had good reason to be pessimistic.

In the midst of general confusion about the forthcoming operation, pessimism seemed the order of the day, and vital planning went awry. Luettwitz himself doubted whether the offensive would succeed. The Germans had to achieve surprise, and the Allied air forces somehow had to be neutralized. Hitler would have to deliver both a sufficient quantity of fuel and the 2000 German aircraft he had promised on December 11, 1944. Perhaps the attacking German columns could reach the Meuse, but without divisions to cover their extended flanks and without adequate bridging equipment, there was little hope that they could push farther.

II. ORGANIZATION AND DEPLOYMENT OF UNITS

With the attack scheduled for December 16, 1944, there was good reason for German concern. The number of their soldiers available had steadily decreased, most units had not been rested, and all units encountered significant shortages of organic weapons, tanks, trucks, spare parts, ammunition, and fuel. Moreover, there were no plans to capture enemy supplies, and the success of the operation did not hinge on that possibility. German general staff at all echelons also believed that the enemy had no strategic reserves available on the Continent and that there would be little Allied resistance in the Bastogne area. Both assumptions proved fatally incorrect.

The XLVII Panzer-Corps consisted of the 2.Panzer-Division, the Panzer-Lehr-Division, and the 26.Volksgrenadier-Division, all reinforced by one Volks mortar brigade, one Volks artillery corps, and the 600.Army-Engineer-Battalion for bridging purposes. None was at full strength. The 2.Panzer-Division had been in the rear area for four weeks to rest and refit. It had only 80 percent of its authorized personnel and equipment, but its commanders were seasoned veterans. One panzergrenadier battalion was on bicycles to save fuel and vehicles. It would be totally unfit for combat in the hilly roads of the rugged Ardennes and ultimately would have to be used only for replacement troops.

The Panzer-Lehr-Division had just returned from the Saar area. It had 60 percent of its troops, 40 percent of its tanks and tank destroyers, 60 percent of its guns, and 40 percent of its other types of weapons. One tank battalion had no tanks and, thus, was unavailable for the attack. In its place, the division received the Schwere-Panzerjäger-Abteilung 539 (Heavy Panzer-Destroyer-Battalion) equipped with 30 percent of its authorized Mark V Panther tank destroyers. Due to previous battle losses, the 26.Volksgrenadier-Division was without one regiment. But the remainder of the division was at full strength and had several seasoned senior commanders. Many subordinate commanders, however, were without previous combat experience, and the division had not been trained in offensive operations. Organizations later assigned to the XLVII Panzer-Corps in operations around Bastogne would arrive in poor condition, with strengths ranging from 50 to 70 percent. These included the 9.Panzer-Division and 116.Panzer-Divsion, the 3.Panzergrenadier-Division, the 15.Panzergrenadier-Division, and the Führer-Begleit-Brigade (Führer Escort Brigade).

Following a heavy artillery bombardment at 0500 on December 16, 1944, the Germans launched their offensive, gaining surprise and immediate local successes in all sectors. In the American VIII Corps sector alone, twenty-five German divisions were attacking. They struck and advanced through the veteran, but weary, 28-ID and 4-ID as well as the green 106-ID and the equally inexperienced 14.CG. Only in the 4-ID sector was action light. The only US corps reserve consisted of an armored combat command and four battalions of combat engineers. Amid much confusion and disorganization in the American units, the Germans advanced steadily, but not as rapidly as they had hoped. Poor roads became overcrowded, and small pockets of determined resistance waged by American infantry and armored units slowed, but did not stop, the German advance. The Allied high command realized that Bastogne was threatened and reserves were needed immediately. Accordingly, on December 17, the 101-A/B, then in Camp Mourmelon, France, resting and refitting after operations in Holland, was alerted to move to the vicinity of Bastogne. Bastogne, if held, could interrupt lines of communication as the Germans continued their attack westward. But, meanwhile, the VIII Corps’ defenses were crumbling, and the Germans, who averaged four to eight miles in advance on the first day, were within eleven miles of Bastogne. Time had become a critical factor. The race was On!

The 101-A/B, the unit chosen to stem the advance, was a well-trained, veteran outfit. Prior to and during its deployment in Europe, the unit had placed special training emphasis on decentralizing and massing artillery, the repair and operation of enemy equipment, air-ground liaison, signal security, night operations, and defense against mechanized, aerial, and infantry infiltration. Its strength at the time of the alert was 805 officers and 11.035 enlisted men. Included in its organization were four infantry regiments and all supporting arms, though there were shortages of personnel and equipment. Its commander, Gen Maxwell D. Taylor, was in the USA. His deputy, Gen Gerald J. Higgins, was in England with five senior and sixteen junior officers. Therefore, command of the division for the operations around Bastogne fell to Gen Anthony C. McAuliffe, the division’s artillery commander. In record time, he got the division on the road moving toward the town of Werbomont, twenty-five miles north of Bastogne, where he was originally ordered to report. In an oversight that could have led to catastrophe, however, no one had informed the division that it was now attached to VIII Corps. The advance party that reached Werbomont on the night of December 18, only then discovered they were meant to report to Bastogne.

Gen McAuliffe’s fortuitous stop in Bastogne to confer with Gen Middleton in the late afternoon that day saved the rest of the division the same fate. Learning of his attachment to VIII Corps and receiving orders from Middleton to defend Bastogne, McAuliffe made immediate preparations to reroute and receive the division. This was accomplished superbly by a few staff officers without the help of any advance party. As McAuliffe’s columns moved through heavy traffic toward Bastogne, forty tanks from Combat Command B (10-AD), the 705-TDBth Tank Destroyer Battalion (with 76-MM self-propelled guns), and two battalions of 155-MM artillery were ordered to Bastogne and be attached to the 101-A/B. These organizations and a makeshift replacement pool of stragglers – Team Snafu – from US elements withdrawing near Bastogne, would bolster the defense of the 101-A/B throughout the critical period in the battle for the city and its perimeter.

Even as the 101st and its attachments were moving into Bastogne during the night of Dec 18, the German advance had moved rapidly down the Wiltz-Bastogne road to a point just three kilometers from the town. There they collided with the first elements of the 101st. With the VIII Corps evacuating the area, the defense of Bastogne became the division’s task. The paratroopers had barely won the race for the town; now the problem was to hold it. In the early stages of the German advance, supply difficulties had not been a particularly critical issue. While some German division commanders had hoped to capture American supplies, none relied on that possibility as a primary source of resupply. Fuel, however, was immediately in short supply because only half the promised initial issue was delivered. Furthermore, unusually heavy consumption rates, brought about by rough terrain and poor weather near Bastogne, further drained the meager fuel supplies. Throughout the operation, the fuel situation would only worsen for the Germans. But until Dec 18, the XLVII Corps heading for Bastogne was still in good fighting shape: there was good cooperation throughout the corps; reports were timely; communications were good; troop morale was reasonably high; the attack had begun on time on the 16th, and the US 28th Infantry Division’s first line of defense had been broken.

Even so, there had been some serious problems that threw the XLVII Cors off its timetable. Unanticipated high water across the Our River caused delays while engineers extended and bolstered bridges for tanks to cross. Elimination of abatis constructed by both Americans and Germans while on the defensive, and the filling in of craters caused additional delays. Because of poor roads and few bridges, two assault divisions were involved in a bottleneck at one vital bridge. These hindrances, combined with a stiffening American resistance that was in greater depth than the Germans expected, prevented the Panzer-Lehr-Division from arriving in Bastogne at the appointed time, 1800 on Dec 18. Had the Germans arrived on schedule, the 101st would have been five kilometers west of the town. After the Germans intercepted an alert message by the 101st on Dec 17 and discovered the paratroopers projected Dec 18 arrival time in Bastogne, greater pressure was placed on the XLVII Corps for a more rapid advance. However, there was no advice on how the corps should overcome the obstacles it faced nor was there any offer of assistance.

As the 101st and its attachments, practically on the run, formed a perimeter in the villages around Bastogne during the night of Dec 18, the tide of events had begun to turn. German troops, pressed by their commanders for a faster rate of advance, were near exhaustion. Previous losses of men and equipment and the prospects for more of the same sapped their will to fight. The American units they now faced were fresh, motivated, and in control of Bastogne. But Bastogne would be hotly contested in the week ahead.

By any comparison, the Americans, with a light infantry paratroopers division, some additional artillery, forty tanks, and a tank destroyer battalion, should not have been a match for the superior German forces, which consisted of two panzer divisions and a volks grenadier division; yet they were. Their ability to resist the Germans at Bastogne was enhanced by their timely occupation of the town. Low German morale also strengthened the US resolve. The Germans of the Army Group West and the 5.Panzer-Army had no choice but to sustain the momentum of the offensive at all costs in accordance with Hitler’s demands. Ultimately, German commanders who were too far removed from the action would make fateful decisions that would allow the lightly equipped defenders of Bastogne to survive.