Document Source: Company in Defense and Withdrawal, Operations of Able Company, 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division near Rencheux, Belgium, December 22 to December 24, 1944. Personal Experience of a Company Commander, Major Jonathan E. Adams Jr

This archive covers the operation of Able Company, 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division near Rencheux, Belgium during the period of December 22 to December 25, 1944. In order to orient the reader with the situation, and also to acquaint him with the state of morale, training, and equipment, it is necessary to go back to November 12, 1944. It was on this date that the 82nd Airborne Division was relieved from the lines at Nijmegen, Holland, and sent to Sissonne, France. Their camp was set up in a French Caserne. It was highly logical to assume that the Division had been withdrawn to prepare for an Airborne assault across the Rhine River sometime in early 1945. This was anticipated with enthusiasm since many airborne officers felt that the services of this type of unit were wasted on other than airborne missions.

When the division arrived at Sissonne, they were not immediately re-outfitted or re-equipped. In fact, the division had a very low theater priority. That equipment that the division did have, was, for the most part, either salvaged or sent back to the troops fighting in Germany. Clothing and shoes were also turned in for salvage, while the weapons were sent to the Ordnance for a very necessary check-up. Because there were no replacements available, the division was not immediately built up to strength again. Their Parachute school in England was helping out a little, but there were very few volunteers for Parachute duty at this time.

The first few weeks after the division’s arrival at Sissonne, training was kept to a minimum, and stress was laid on rebuilding the morale of the troops. Recreation played an important role in the schedule. Most of the time was taken up by athletics, but each day there was also either an inspection or close order drill. Since spit and polish were emphasized the division gradually regained some of the disciplines which an outfit invariably loses in combat. For entertainment, a system of passes to Paris was instituted, and the USO and French shows from Paris were imported at Sissonne.

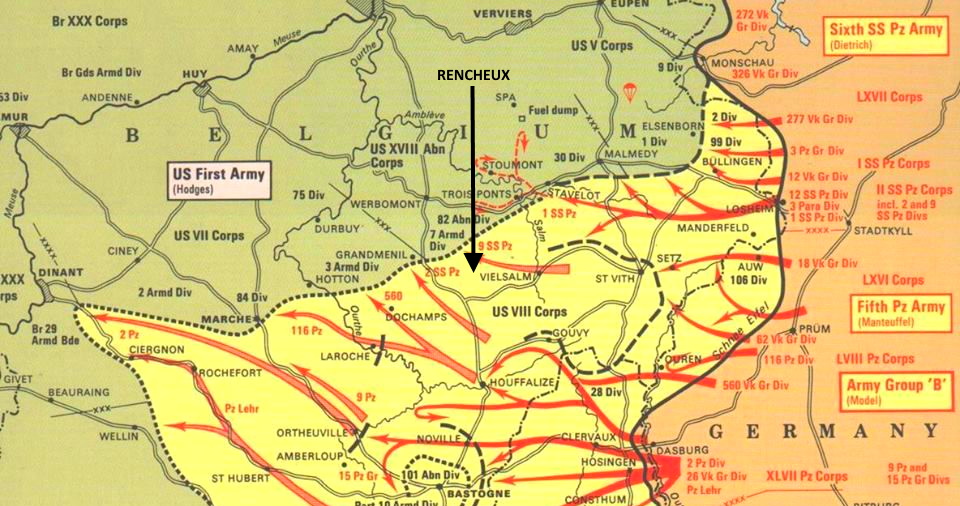

On December 1 approximately, training became merely intense, and it soon became obvious by its pattern that it was for a gradual buildup to an Airborne drop. When the 82-A/B was about to begin to feel sure of a comfortable winter in the communication zone, the Germans decided to change things by starting their winter offensive in Belgium. As the German attack progressed, it became clear to SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces) that it would be necessary to move the Paratroopers into the battle to help to stem the tide. The possibility of losing the use of the Airborne Division in a spring offensive would have to be risked in the face of the present emergency.

Thus it was, that Gen Gavin was alerted on the night of December 17, around 1930. He was told to be prepared to move the 82-A/B to Bastogne, Belgium, the next day (*82-A/B Report). At around 2000, the Company Commanders had been alerted and were given the very fragmentary orders Be prepared to move to Bastogne, Belgium, by truck by 1100 tomorrow (*Personal Knowledge).

Thus it was, that Gen Gavin was alerted on the night of December 17, around 1930. He was told to be prepared to move the 82-A/B to Bastogne, Belgium, the next day (*82-A/B Report). At around 2000, the Company Commanders had been alerted and were given the very fragmentary orders Be prepared to move to Bastogne, Belgium, by truck by 1100 tomorrow (*Personal Knowledge).

At first, it seemed like an impossible task. Weapons were still in the Ordnance. The requisitions on clothing had not been filled, and winter clothing was virtually non-existent in the division. However, it was only a short time before the Ordnance and Quartermaster depots in the immediate vicinity were rushing equipment to the division. One K-ration per man was issued, and ammunition was distributed from each Regiment’s basic load. As if there were no confusion already, the rifle companies received 30 replacements at 0300 on December 18 (*Personal Knowledge). This necessitated assigning the new men, checking their equipment, making up shortages, preparing new rosters, and briefing them.

However, by 1100, December 18, the Regiments were loaded on the trucks and on their way. It is true that some of the men were pitifully short of clothing and equipment. Many had no overcoats or gloves. Probably the item in the poorest condition was the footwear. Weapons were also still not in A-1 shape. A good many of the machine guns were without tripods, and the mortars were without bipods. Still, the important thing was that the division was on the road. That they were able to move in such a short time was because of experience in the past, which usually consisted of sudden commitments.

The division followed the general route via Sissonne, Charleville, Recogne Sprimont (Bastogne), Houffalize and Werbomont. While en route the march objective was changed from Bastogne to Werbomont (*82-A/B Report). Altogether, the entire division had moved 150 miles, and in less than 40 hours after the initial alert; while some of the combat elements had gone into position in less than twenty hours (*Personal Knowledge).

GENERAL SITUATION

The best way to describe the conditions at this time is to give the furthest points reached by the Germans’ rapid advance. It must be kept in mind, however, that the situation was so fluid that there was no set front line, but that there were American forces still fighting behind the enemy. By December 19, the Germans had reached Stavelot and had sent patrols forward to Trois Ponts. They were driving hard towards St Vith and Bastogne. Within two hours after the last element of the 82-A/B had passed through Houffalize, that town was taken by advance elements of the German attack. Upon arrival at Werbemont, the regiments of the division set up an all-around defense and immediately sent out reconnaissance patrols in an effort to locate the enemy. Numerous German patrols were soon contacted in the vicinity of Trois Ponts, but it was found that the Germans had no large bodies of troops in this area as yet. On the afternoon of December 19, the 82-A/B occupied and organized the high ground to the east and south of Werbomont. (*Personal Knowledge)

The best way to describe the conditions at this time is to give the furthest points reached by the Germans’ rapid advance. It must be kept in mind, however, that the situation was so fluid that there was no set front line, but that there were American forces still fighting behind the enemy. By December 19, the Germans had reached Stavelot and had sent patrols forward to Trois Ponts. They were driving hard towards St Vith and Bastogne. Within two hours after the last element of the 82-A/B had passed through Houffalize, that town was taken by advance elements of the German attack. Upon arrival at Werbemont, the regiments of the division set up an all-around defense and immediately sent out reconnaissance patrols in an effort to locate the enemy. Numerous German patrols were soon contacted in the vicinity of Trois Ponts, but it was found that the Germans had no large bodies of troops in this area as yet. On the afternoon of December 19, the 82-A/B occupied and organized the high ground to the east and south of Werbomont. (*Personal Knowledge)

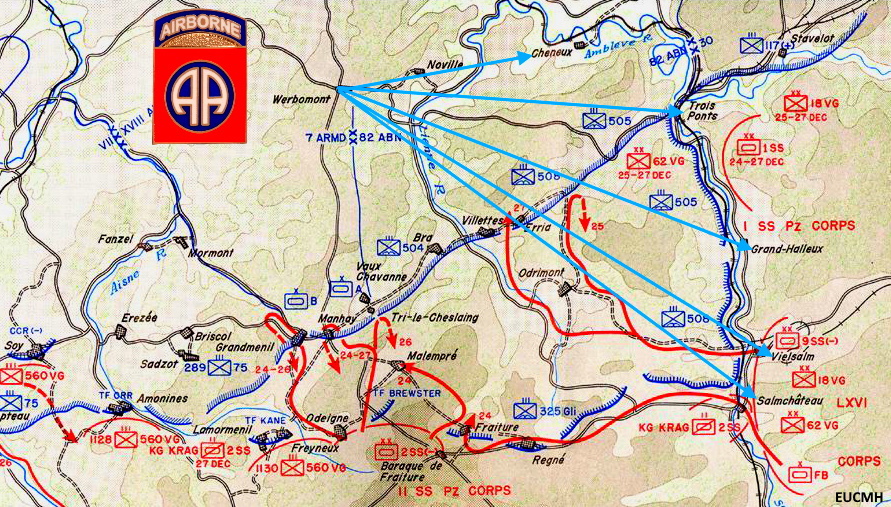

On the following afternoon, the division received orders to establish a defensive line from Cheneux through Trois Ponts, Grand Halleux,

On the following afternoon, the division received orders to establish a defensive line from Cheneux through Trois Ponts, Grand Halleux,

REGIMENTAL SITUATION

The 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment was assigned the sector extending from Vielsalm to Salmchâteau. The Regiment, in turn, assigned the mission of defending the ground immediately around Vielsalm to the 1st Battalion. (*Personal Knowledge)

The 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment was assigned the sector extending from Vielsalm to Salmchâteau. The Regiment, in turn, assigned the mission of defending the ground immediately around Vielsalm to the 1st Battalion. (*Personal Knowledge)

BATTALION SITUATION

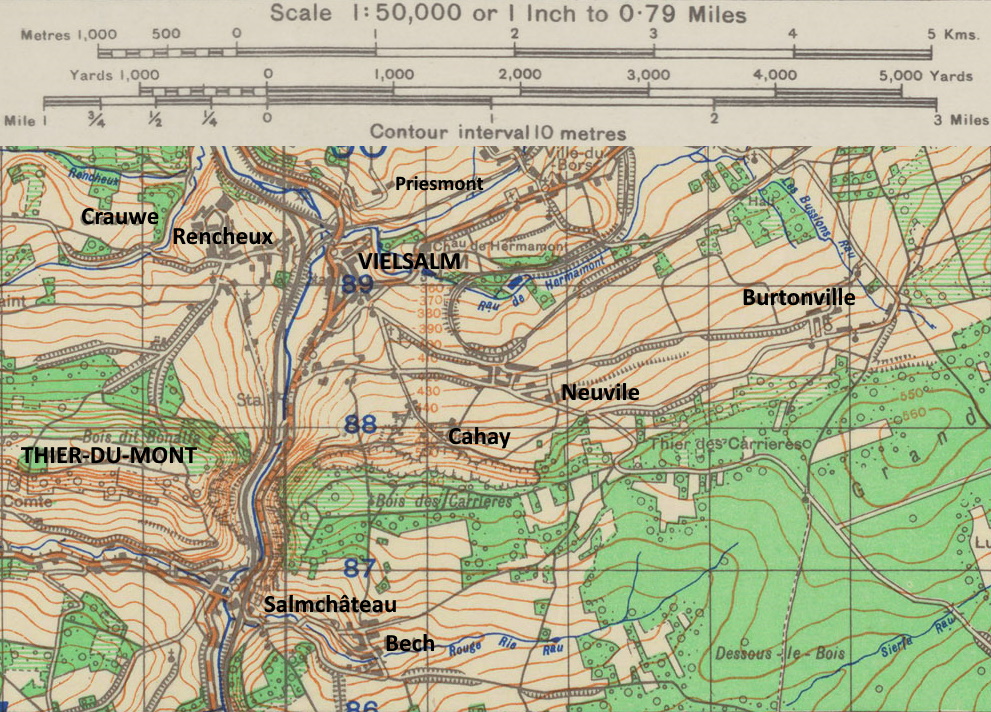

On the night of December 20, the 1st Battalion moved by motor to Rencheux, across the river from their objective. Intelligence had been very vague. The Battalion commander was merely told that the Command Post of Gen Allan Jones’ 106th Infantry Division was believed to be located in Vielsalm, and that there were no Germans there. The move to Rencheux proved to be uneventful. However, in the town itself, everything was in a state of confusion. At a road block covered by a 57-MM AT gun, advance guards of the Battalion made their first contact with the 106-ID. This gun was protecting the approaches from the west. The 106-ID had had some disastrous experiences of having their positions overrun by Germans wearing American uniforms, and they did not intend to let it happen again. The night was pitch black, and to make matters worse, the 82-A/B had not received the password. By identifying themselves as American Paratroopers, the 1st Battalion only managed to arouse further, the suspicions of the men of the 106-ID. Finally, after much time had been lost, positive identification was made, and the Battalion proceeded on into the town. However, progress proved very slow because they would run into another outpost every few yards, and the same procedure of identification would have to be repeated.

On the night of December 20, the 1st Battalion moved by motor to Rencheux, across the river from their objective. Intelligence had been very vague. The Battalion commander was merely told that the Command Post of Gen Allan Jones’ 106th Infantry Division was believed to be located in Vielsalm, and that there were no Germans there. The move to Rencheux proved to be uneventful. However, in the town itself, everything was in a state of confusion. At a road block covered by a 57-MM AT gun, advance guards of the Battalion made their first contact with the 106-ID. This gun was protecting the approaches from the west. The 106-ID had had some disastrous experiences of having their positions overrun by Germans wearing American uniforms, and they did not intend to let it happen again. The night was pitch black, and to make matters worse, the 82-A/B had not received the password. By identifying themselves as American Paratroopers, the 1st Battalion only managed to arouse further, the suspicions of the men of the 106-ID. Finally, after much time had been lost, positive identification was made, and the Battalion proceeded on into the town. However, progress proved very slow because they would run into another outpost every few yards, and the same procedure of identification would have to be repeated.

The Command Post of the 106-ID was located in Rencheux, instead of Vielsalm as believed. This had originally been the division rear CP, but the forward one had moved back from St Vith when two regiments of the 106-ID, the 422-IR and the 423-IR had been surrounded by the elements of Manteufell 5.Panzer-Army in the vicinity of Bleialf-Schoenberg-St Vith a few days earlier. At this time the division was out of contact with these two regiments. Nevertheless, a CP was found to be located at Vielsalm, but it was that of Gen Hasbrouck’s 7th Armored Division while the bulk of that division was located between Vielsalm and St Vith.

The Command Post of the 106-ID was located in Rencheux, instead of Vielsalm as believed. This had originally been the division rear CP, but the forward one had moved back from St Vith when two regiments of the 106-ID, the 422-IR and the 423-IR had been surrounded by the elements of Manteufell 5.Panzer-Army in the vicinity of Bleialf-Schoenberg-St Vith a few days earlier. At this time the division was out of contact with these two regiments. Nevertheless, a CP was found to be located at Vielsalm, but it was that of Gen Hasbrouck’s 7th Armored Division while the bulk of that division was located between Vielsalm and St Vith.

The commander of the 1/508-PIR decided that, with all this protection, and because there had been no previous reconnaissance, nothing would be accomplished by attempting to occupy positions in the dark. Consequently, the battalion was bivouacked for the remainder of the night in the Belgian Army Caserne in Rencheux.

COMPANY SITUATION

At dawn the next morning, December 21, a preliminary reconnaissance was made and the companies were assigned sectors. Able Co was given the mission of occupying a position to the west of the Salm River astride the main road. Baker Co was on Able Co’s left, and the 3/112-IR (28th Infantry Division), who was cut off in that area were attached to the 508-PIR, and occupied positions on Able Co’s right (*Personal Knowledge). The company commander of Able Co was told that there would be no withdrawal and that this would be where the 82-A/B would make its stand. In order to better understand Able Co’s position at this time, a brief terrain analysis is in order. The Salm river is actually a small stream about ten feet wide, running from north to south. Under ordinary circumstances, this would not be considered much of a barrier. However, at this point in the country, the current was very swift and had cut a gorge about eight feet deep, thus being unfordable to both vehicles and foot soldiers. Two railroad bridges and a wooden road bridge were the only means of crossing. On the eastern side of the river and immediately to the north of the road crossing, the terrain was heavily wooded. The ground rose very gradually for about 200 yards, and then, very sharply. In Vielsalm there were buildings on a cliff overlooking the river. These were about 50 to 75 feet above the stream bed. On the west side of the river, a railroad ran parallel, to the stream. Beyond it, the ground rose sharply to the height of 100 feet, for a stretch of about 400 yards.

The platoons were assigned their defensive positions, the first platoon on the right, the third platoon on the left, and the second platoon in reserve. In assigning these positions, the company commander kept two things in mind. First, there would be no withdrawal. Consequently, he disregarded any consideration as to routes for this. He reasoned that re-supply and the feeding of the platoons could be accomplished at night under the cover of darkness. Secondly, his mission was to keep the enemy from crossing the Salm River. It was, therefore, necessary for some instances to sacrifice fields of fire for observation on the opposite bank of the Salm.

The third platoon was to maintain contact with Baker Co. There was a gap of about 300 yards between the two companies. However, it was open ground, and could easily be covered by fire in the daytime, and by patrols at night. Two squads of the third platoon were placed on the slight knoll located in the triangle formed by the railroads. Once contact had been made with the Germans, it would be impossible to move to or from this knoll in the daytime. However, it was the only site that could command the banks of the river immediately to the north of the road bridge.

The first platoon on the right was in somewhat the same plight as the third. They were located on the forward slopes of a hill, completely devoid of any cover or concealment. The second platoon in reserve was astride the road. Because of the numerous houses, it was necessary to have them well-forward. At the most, they were only 50 yards behind the two front platoons.

Able Co had three days in which to organize their position. Every advantage was taken of this much-appreciated delay from combat. Individual foxholes were dug, and the overhead cover was constructed, so that each one was virtually a fortress. The wire was laid to all positions. Each platoon was equipped with German field telephones which had been secured in previous campaigns. Officers and non-commissioned officers became acquainted with the replacements they had received four days previously. Some of the more serious shortages in equipment, such as overcoats, shoes, and machine gun tripods, were made up from the meager supplies that the division had managed to secure. Shortages of supply were also supplemented by equipment thrown away by retreating American forces. Footwear more and more became an item of importance. Snow followed by rain had created a slush which soon penetrated the parachute boots everyone was wearing. It did not take the men long to locate a supply dump of the 106-ID containing overshoes. Requests were made to have these issued but were refused. By various means, the men of Able Co managed to secure overshoes nevertheless. As this supply dump was captured a few days later, this proved to be a great breach of supply discipline.

It was soon clear that the 7-AD and the remnants of the 106-ID would not be able to hold the salient across the river. The road through Able Co’s position was one of the main routes of retreat. During December 22 and December 23, there was a constant flow of traffic from the front. Able Co’s commander was greatly concerned about the effect it would have on the morale of the men to see everyone taking off to the rear, knowing that they themselves were to stay. He was especially concerned that the men might become infected with the state of terror of the majority of these retreating forces. It was no uncommon occurrence to see groups of ten and twenty men, who had thrown all their arms away in order that they might travel faster. The Commander of Able Co put out the order that none of his men would be allowed to speak to any of these troops, and that they would not be allowed to stop in the Able Co area. His fears, however, were unfounded.

It was soon clear that the 7-AD and the remnants of the 106-ID would not be able to hold the salient across the river. The road through Able Co’s position was one of the main routes of retreat. During December 22 and December 23, there was a constant flow of traffic from the front. Able Co’s commander was greatly concerned about the effect it would have on the morale of the men to see everyone taking off to the rear, knowing that they themselves were to stay. He was especially concerned that the men might become infected with the state of terror of the majority of these retreating forces. It was no uncommon occurrence to see groups of ten and twenty men, who had thrown all their arms away in order that they might travel faster. The Commander of Able Co put out the order that none of his men would be allowed to speak to any of these troops, and that they would not be allowed to stop in the Able Co area. His fears, however, were unfounded.

The 1st Sergeant, in the meantime, was combatting rumors. He finally solved the problem by starting his own, and later tracking them down and revealing their source. As a result, the men would not believe anything at all, unless it was given as part of an official order. On December 22, a platoon of Engineers from Dog Co 325th Glider Infantry Regiment prepared the three bridges in front of Able Co for demolition. A small detachment was left to supervise their destruction (*Report 1/508-PIR). Able Co was given the responsibility of seeing that this was accomplished. The company commander instructed the 2nd platoon leader to place a squad of men as outposts at the approaches to the bridges. During daylight, these were to be well forward, but at night the platoon leader was to pull them in so that they would not be cut off. On the morning of December 23, the company commander was told that the 7-AD was withdrawing its screening forces. The northern railway bridge would be blown at 1500, and the other two bridges would be destroyed at 2200, or immediately after all the troops of the 7-AD had been withdrawn, whichever was earlier. The company was alerted; especially the outposts of the 2nd platoon whose leader made a special point of checking the demolition charges.

The 1st Sergeant, in the meantime, was combatting rumors. He finally solved the problem by starting his own, and later tracking them down and revealing their source. As a result, the men would not believe anything at all, unless it was given as part of an official order. On December 22, a platoon of Engineers from Dog Co 325th Glider Infantry Regiment prepared the three bridges in front of Able Co for demolition. A small detachment was left to supervise their destruction (*Report 1/508-PIR). Able Co was given the responsibility of seeing that this was accomplished. The company commander instructed the 2nd platoon leader to place a squad of men as outposts at the approaches to the bridges. During daylight, these were to be well forward, but at night the platoon leader was to pull them in so that they would not be cut off. On the morning of December 23, the company commander was told that the 7-AD was withdrawing its screening forces. The northern railway bridge would be blown at 1500, and the other two bridges would be destroyed at 2200, or immediately after all the troops of the 7-AD had been withdrawn, whichever was earlier. The company was alerted; especially the outposts of the 2nd platoon whose leader made a special point of checking the demolition charges.

At 1500 hours the railroad bridge was blown as planned. Information was received at about the same time that the 3rd Battalion had made contact with the enemy at Salmchâteau. To the north, at Trois Ponts, the 504-PIR had contacted the enemy on the previous day, while the withdrawal of the 7-AD was progressing effectively in the Able Co sector.