28-ID – Background

On Mar 12, 1879, Governor Henry Hoyt signed the General Order Number One appointing Maj Gen John F. Hartranft as the first division commander of the National Guard of Pennsylvania. From Aug 11 to Aug 18 1894, Camp Samuel W. Crawford was the Division Encampment at Gettysburg. The division was mustered into service for the Spanish–American War in 1898. Pennsylvania was initially levied 10.800 men, in ten infantry regiments and four artillery batteries. The entire division was mustered into service between May 6 and July 22, and while 8.900 men had assembled at Mount Gretna for the muster parade on Apr 28, 1898, there was no difficulty in raising 12.000 men for service in two and a half months. However, only three regiments, the 4-R, the 10-R, and the 16-R, three artillery batteries, and three cavalry troops were deployed, to Puerto Rico. The 10-R was then sent to the Philippines, being ordered home on Jun 30, 1899, the division being called up to respond to labor disturbances in 1877 and 1900. In 1914, the division was designated the 7th Division as part of a broad reorganization of the National Guard. On Jun 29, 1916, the 7th Division was mustered into service at Mount Gretna and deployed to El Paso, Texas, to serve along the Mexican border as the Regular Punitive Expedition entered Mexico. Maj Gen Charles M. Clement commanded, directing the 1st Brigade comprising the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Regiments, the 2nd Brigade the 10th, 16th, and 18th Regiments, and the 3rd Brigade the 4th, 6th, and 8th Regiments. There was also a regiment of cavalry and one of artillery, plus two companies of signals troops and medical units. The camp outside El Paso gained the title of Camp Stewart after the Adjutant General, Thomas J. Stewart.

On Mar 12, 1879, Governor Henry Hoyt signed the General Order Number One appointing Maj Gen John F. Hartranft as the first division commander of the National Guard of Pennsylvania. From Aug 11 to Aug 18 1894, Camp Samuel W. Crawford was the Division Encampment at Gettysburg. The division was mustered into service for the Spanish–American War in 1898. Pennsylvania was initially levied 10.800 men, in ten infantry regiments and four artillery batteries. The entire division was mustered into service between May 6 and July 22, and while 8.900 men had assembled at Mount Gretna for the muster parade on Apr 28, 1898, there was no difficulty in raising 12.000 men for service in two and a half months. However, only three regiments, the 4-R, the 10-R, and the 16-R, three artillery batteries, and three cavalry troops were deployed, to Puerto Rico. The 10-R was then sent to the Philippines, being ordered home on Jun 30, 1899, the division being called up to respond to labor disturbances in 1877 and 1900. In 1914, the division was designated the 7th Division as part of a broad reorganization of the National Guard. On Jun 29, 1916, the 7th Division was mustered into service at Mount Gretna and deployed to El Paso, Texas, to serve along the Mexican border as the Regular Punitive Expedition entered Mexico. Maj Gen Charles M. Clement commanded, directing the 1st Brigade comprising the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Regiments, the 2nd Brigade the 10th, 16th, and 18th Regiments, and the 3rd Brigade the 4th, 6th, and 8th Regiments. There was also a regiment of cavalry and one of artillery, plus two companies of signals troops and medical units. The camp outside El Paso gained the title of Camp Stewart after the Adjutant General, Thomas J. Stewart.

On Sept 19, one brigade was sent home. On Nov 14, the 1st Artillery left for home; the 18th Infantry left for Pennsylvania on Dec 19; and the remainder of the division between Jan 2–19, 1917. It appears that most of the division was mustered out of service on Feb 23, 1917, at Philadelphia. The remnant left on the border included the 8th and 13th Regiments, the newly formed 3rd Artillery and Charlie Co of the Engineers. They were released from active service in Mar 1917. However, the call up process for World War I was underway as these units left the border. The 13th Regiment began its return home from Texas on Mar 21, 1917, but en route, were told that their mustering-out orders had been rescinded.

On Sept 19, one brigade was sent home. On Nov 14, the 1st Artillery left for home; the 18th Infantry left for Pennsylvania on Dec 19; and the remainder of the division between Jan 2–19, 1917. It appears that most of the division was mustered out of service on Feb 23, 1917, at Philadelphia. The remnant left on the border included the 8th and 13th Regiments, the newly formed 3rd Artillery and Charlie Co of the Engineers. They were released from active service in Mar 1917. However, the call up process for World War I was underway as these units left the border. The 13th Regiment began its return home from Texas on Mar 21, 1917, but en route, were told that their mustering-out orders had been rescinded.

The division moved to Camp Hancock, Ga., in Apr 1917, and was there when the entire division was federalized on Aug 5. From May to Oct 1917, the division was reorganized into the two-brigade, four regiment scheme, and thus became the 28-D. It thus comprised the 55th Infantry Brigade (109th and 110th Infantry Regiments) and the 56th Infantry Brigade (111th and 112th Infantry Regiments). Other units included the 107th, 108th, 109th and 229th Field Artillery Battalions and the 103rd Engineer Combat Battalion. The men arrived there in summer uniforms, which were not replaced by winter ones until the winter was well along. Adequate blankets were not available until January. Training equipment was woeful. There was but one bayonet for each three men; machine guns made of wood; and there was but one 37-MM gun for the whole division.

By May 1918, the division had arrived in Europe, and began training with the British. On Jul 14, ahead of an expected German offensive, the division was moving forward, with most of it committed to the second line of defense south of the Marne River and east of Château-Thierry. As the division took up defensive positions, the Germans commenced their attack, which became the Battle of Château-Thierry, with a fierce artillery bombardment. When the German assault collided with the main force of the 28-D, the fighting became bitter hand-to-hand combat. The 28-D repelled the German forces and decisively defeated their enemy. However, four isolated companies of the 109th and 110th Infantry stationed on the first defensive line suffered heavy losses. After the battle, Gen John C. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), visited the battlefield and declared that the 28-D soldiers were Men of Iron and named the 28-D as his Iron Division. The 28-D developed a red keystone-shaped shoulder patch, officially adopted on Oct 27 1918.

By May 1918, the division had arrived in Europe, and began training with the British. On Jul 14, ahead of an expected German offensive, the division was moving forward, with most of it committed to the second line of defense south of the Marne River and east of Château-Thierry. As the division took up defensive positions, the Germans commenced their attack, which became the Battle of Château-Thierry, with a fierce artillery bombardment. When the German assault collided with the main force of the 28-D, the fighting became bitter hand-to-hand combat. The 28-D repelled the German forces and decisively defeated their enemy. However, four isolated companies of the 109th and 110th Infantry stationed on the first defensive line suffered heavy losses. After the battle, Gen John C. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), visited the battlefield and declared that the 28-D soldiers were Men of Iron and named the 28-D as his Iron Division. The 28-D developed a red keystone-shaped shoulder patch, officially adopted on Oct 27 1918.

During WW-I, the division was involved in the Meuse Argonne, Champagne Marne, Aisne Marne, Oise Aisne, and Ypres Lys (France) battles. The cost of this campaign took a total of 14.139 casualties (2.165 killed and 11.974 wounded).

During WW-I, the division was involved in the Meuse Argonne, Champagne Marne, Aisne Marne, Oise Aisne, and Ypres Lys (France) battles. The cost of this campaign took a total of 14.139 casualties (2.165 killed and 11.974 wounded).

Inter War Period

The division was demobilized on May 17, 1919, at Camp Dix, New Jersey. The 28-D was reorganized and federally recognized on Dec 22, 1921, in the Pennsylvania National Guard at Philadelphia. The location of the Headquarters was changed on Mar 12, 1933, to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. An honor battalion of Pennsylvania National Guardsmen of the Iron Division dedicated the Pennsylvania World War One Memorial in the Argonne, France, in 1928.

World War Two

The division was activated on Feb 17, 1941, at Camp Livingston, Louisiana. Lineage data gives the same date, but as the date the HHD 28th Division, was inducted into federal service Feb 17, 1941, at Harrisburg and Philadelphia. It was reorganized and re-designated on Feb 17, 1942, as HQs, 28th Infantry Division. That same month the division was reorganized, the brigades were disbanded, and the 111th Infantry Regiment was detached and reorganized as a separate regimental combat team, initially used to guard important Eastern Seaboard industrial facilities. The division trained in the Carolinas Manoeuvre in Virginia, Louisiana, Texas, and Florida. It went overseas on Oct 8, 1943.

28-ID – CGs

Gen John F. Hartranft 1879–1889, Gen George R. Snowden 1889–1900, Gen Charles Miller 1900–1906, Gen John P. S. Gobin 1906-1907, Gen John A. Wiley 1907–1909, Gen Wendell P. Bowman 1909–1910, Gen Charles B. Dougherty 1910–1915, Gen Charles M. Clement 1915–1917, Gen Charles H. Muir 1917–1918, Gen William H. Hay 1918–1919, Gen Charles H. Muir 1919–1920, Gen William G. Price, Jr. 1920–1933, Gen Edward C. Shannon 1933–1939, Gen Edward Martin 1939–1942, Gen James Garesche Ord 1942–1942, Gen Omar N. Bradley 1942–1943, Gen Lloyd D. Brown 1943–1944, Gen James E. Wharton August 13 1944 and Gen Norman D. Cota 1944–1945.

For most of August the division remained engaged in tough fighting in the infamous hedgerow country of Normandy. This grim slugging match changed to rapid pursuit in late August following the Allied breakout from the Normandy beachhead. Moving on foot and by truck, the 28-ID raced eastward in pursuit of the German Army. During the last ten days of August the division moved more than 270 miles. For the infantry, most of those miles were on foot. On Aug 29, the 28-ID enjoyed the privilege of parading through the streets of Paris. The German commander of the city declared Paris an open city, so there was no fighting for the division.

For most of August the division remained engaged in tough fighting in the infamous hedgerow country of Normandy. This grim slugging match changed to rapid pursuit in late August following the Allied breakout from the Normandy beachhead. Moving on foot and by truck, the 28-ID raced eastward in pursuit of the German Army. During the last ten days of August the division moved more than 270 miles. For the infantry, most of those miles were on foot. On Aug 29, the 28-ID enjoyed the privilege of parading through the streets of Paris. The German commander of the city declared Paris an open city, so there was no fighting for the division.

Instead there was the adulation of thousands of liberated Parisians. The parade actually diverted the Keystone Division from its pursuit of the Germans, but provided a valuable American show of support for the government of the leader of the Free French Forces, Gen Charles De Gaulle. Whatever the purpose, the parade was a high point for many of the soldiers and leaders of the division. The parade didn’t last long. The division regained contact with scattered elements of the German Army on the eastern edge of the city and the pursuit was on again.

Instead there was the adulation of thousands of liberated Parisians. The parade actually diverted the Keystone Division from its pursuit of the Germans, but provided a valuable American show of support for the government of the leader of the Free French Forces, Gen Charles De Gaulle. Whatever the purpose, the parade was a high point for many of the soldiers and leaders of the division. The parade didn’t last long. The division regained contact with scattered elements of the German Army on the eastern edge of the city and the pursuit was on again.

By the end of August, the 28-ID was well on its way to becoming a capable combat unit. It had suffered from the inevitable mistakes common for divisions during their first combat action. Although slow to get started, under the solid leadership of Gen Norman Cota, the division was beginning to master the fundamentals required for success in combat. This gain in combat experience came at a high price. Little more than a month of combat had cost the division in excess of 2000 casualties. Considering that approximately 80 percent of all casualties were infantrymen, this meant that the infantry regiments had lost more than 30 percent of their strength in riflemen. To make matters worse, casualties among small unit leaders made up a significant portion of these losses. It would take some time for the division to recover from such losses.

The long supply routes and lack of trucks dramatically slowed the flow of replacements and supplies. Ammunition, particularly artillery, was in very short supply. Fortunately for the 28-ID, at the end of August, German resistance remained light and the weather was kind to soldiers. Disease and non-battle injuries for this period were very small. In the coming months this situation would change dramatically.

September 1944 began with the German Army in full retreat and the jubilant Allied armies close on their heels. For the Allies, the fight to breakout from the Normandy beachhead had been more difficult and costly than anticipated. The subsequent collapse of German defenses in August had caught them equally by surprise. Unable to mount a coherent defense, the German Army withdrew rapidly to the east and the most significant problem confronting the US Army was moving enough fuel and ammo forward to maintain the pursuit. Attached to the US V Corps, the 28-ID was one of the divisions struggling to keep up with the pace of the pursuit.

September 1944 began with the German Army in full retreat and the jubilant Allied armies close on their heels. For the Allies, the fight to breakout from the Normandy beachhead had been more difficult and costly than anticipated. The subsequent collapse of German defenses in August had caught them equally by surprise. Unable to mount a coherent defense, the German Army withdrew rapidly to the east and the most significant problem confronting the US Army was moving enough fuel and ammo forward to maintain the pursuit. Attached to the US V Corps, the 28-ID was one of the divisions struggling to keep up with the pace of the pursuit.

Since the pursuit began in late August, the 28-ID had moved by a combination of vehicle and foot marches. During the first ten days of September the division moved from Paris to near the German border. Resistance was generally light, but for the infantrymen moving on foot the pace was exhausting. At last, on Sept 11, the division halted along the German border near the northern tip of Luxembourg. Ahead of the 28-ID lay the Our River and beyond that, the German’s vaunted Siegfried Line.

Two day later, on Sept 13, the Keystone Division became the first American division to cross the German border in force and start the attack on Germany’s Siegfried Line. This line of prepared defenses included anti-tank obstacles, concrete bunkers, fighting trenches, and thousands of mines.

Two rifle battalions, one each from the 109-IR and the 110-IR, crossed the Our River under the cover of darkness just east of Binsfeld. Reports from recon patrols conducted on Sept 11 and 12, revealed that most of the enemy defenses immediately east of the river were unoccupied. The patrols encountered almost no resistance. Despite such reports, the two battalions moved slowly, unsure of what lay before them. Resistance remained fight and sporadic during the early hours of the attack, but even harassing fire was enough to halt the advance for a lengthy period.

Two rifle battalions, one each from the 109-IR and the 110-IR, crossed the Our River under the cover of darkness just east of Binsfeld. Reports from recon patrols conducted on Sept 11 and 12, revealed that most of the enemy defenses immediately east of the river were unoccupied. The patrols encountered almost no resistance. Despite such reports, the two battalions moved slowly, unsure of what lay before them. Resistance remained fight and sporadic during the early hours of the attack, but even harassing fire was enough to halt the advance for a lengthy period.

The division was critically short of ammunition and as a result, artillery support was almost non-existent. Specialized munitions required for clearing bunkers, such as pole charges, satchel charges, and Bangalore torpedoes were not available. Even small arms ammunition was in short supply.

Based on these shortages Gen Cota restricted the attack to the token effort of one battalion per regiment. Under these circumstances it is easy to see why units did not attack with a great deal of vigor. Both units dug-in that night within sight of the first line of German pillboxes. The next day, Cota lifted the one battalion restriction and the two regiments continued the attack in force. There was also additional support from the division’s artillery. The fire of these weapons, however, had little effect on the massive bunkers. One participant said wem>the fire did little more than dust off the camouflage.

Based on these shortages Gen Cota restricted the attack to the token effort of one battalion per regiment. Under these circumstances it is easy to see why units did not attack with a great deal of vigor. Both units dug-in that night within sight of the first line of German pillboxes. The next day, Cota lifted the one battalion restriction and the two regiments continued the attack in force. There was also additional support from the division’s artillery. The fire of these weapons, however, had little effect on the massive bunkers. One participant said wem>the fire did little more than dust off the camouflage.

The units met with some small successes, but fierce German counter-attacks quickly erased the gains. One such counter-attack on the night of Sept 15 quickly destroyed Fox Co 110-IR. A small German force from SS-Oberführer Otto Baum’s 2.SS-Panzer-Division, well armed with automatic weapons, flame-throwers and supported by tanks made quick work of the defending company. Operations on succeeding days were just as tough on the division. Machine gun fire from well-sited pillboxes pinned down units. German mortar and artillery fire ravaged the ranks of the assault forces. Advancing under such fire proved to be a significant weakness of the infantrymen in the 28-ID. Immobilized by even small amounts of fire, the assaulting riflemen were then vulnerable to indirect fire from artillery and mortars. Leaders attempting to move the men forward quickly became casualties. This was the 28-ID’s first real encounter with such fortified positions, and the skills required were much more complex than those they acquired during training in England. In addition, large numbers of the infantry replacements were fresh to the unit. Many were not even trained riflemen.

In one battalion, 87 out of 100 replacements were hastily converted personnel from anti-tank and anti-aircraft units. The dwindling number of veterans had been in almost continuous operations for more than 50 days and were displaying considerable fatigue.

In one battalion, 87 out of 100 replacements were hastily converted personnel from anti-tank and anti-aircraft units. The dwindling number of veterans had been in almost continuous operations for more than 50 days and were displaying considerable fatigue.

On Sept 17, the division achieved a significant penetration when the 1/110 captured a dominating hill mass near the town of Uttfeld. At this point the division was through the main line of defenses and into the immediate rear of the defender. The penetration, however, was dangerously thin; combat power to exploit the success was noticeably lacking. Other units assigned to V Corps were finding the same tough resistance, and in some locations, enemy counterattacks pushed them back to the west of the Our River.

Gen Leonard T. Gerow, the V Corps commander, took stock of the situation and on September 17 ordered all offensive operations to cease. Within days, much of the corps had withdrawn back across the Our River. After five days of attacks, the 28-ID had run out of steam. Only limited progress was made during the operation, and the cost was very high for the division. During less than a week’s fighting, the division incurred more than 1900 battle casualties.

Out of the casualties, almost 1800 were infantrymen. During the same period, the division reported an additional 830 non battle casualties. The total casualties for the month of September eventually rose to more than 3000. Included in this figure were 230 killed, 1815 wounded, 141 missing, 63 captured, and 961 non battle injuries.

It was at this point that the 28-ID began to encounter its first significant numbers of battle fatigue casualties. The early fighting in Normandy occurred with fresh units that still possessed a high degree of unit cohesion. Most of the personnel in the infantry units had been together for at least a year and some for much longer than that. These strong personal bonds in small units were powerful deterrents to combat fatigue. During the fighting along the Siegfried Line, conditions were much different. The strong personal bonds that characterized the early fighting were rapidly disappearing, as casualties mounted and individual replacements flowed in. German resistance also played a big role, as it stiffened enormously at the Siegfried Line. After the rapid pursuit across France, many soldiers and leaders believed the war was virtually finished. The shock of heavy casualties and tough resistance had a demoralizing affect on the soldiers of the 28-ID. Still another influence was the changing weather in the theater. September grew increasingly wet and cold, a harbinger of the very wet and very cold winter that was soon to arrive in northern Europe. Whatever the combination of factors, battle fatigue cases rose sharply in the 28.

It was at this point that the 28-ID began to encounter its first significant numbers of battle fatigue casualties. The early fighting in Normandy occurred with fresh units that still possessed a high degree of unit cohesion. Most of the personnel in the infantry units had been together for at least a year and some for much longer than that. These strong personal bonds in small units were powerful deterrents to combat fatigue. During the fighting along the Siegfried Line, conditions were much different. The strong personal bonds that characterized the early fighting were rapidly disappearing, as casualties mounted and individual replacements flowed in. German resistance also played a big role, as it stiffened enormously at the Siegfried Line. After the rapid pursuit across France, many soldiers and leaders believed the war was virtually finished. The shock of heavy casualties and tough resistance had a demoralizing affect on the soldiers of the 28-ID. Still another influence was the changing weather in the theater. September grew increasingly wet and cold, a harbinger of the very wet and very cold winter that was soon to arrive in northern Europe. Whatever the combination of factors, battle fatigue cases rose sharply in the 28.

On Oct 9, 1944, Pvt Eddie D. Slovik deserted from his infantry unit. His friend, John Tankey, caught up with him and attempted to persuade him to stay, but Slovik’s only comment was that his mind was made up. Slovik walked several miles to the rear and approached an enlisted cook at a Hqs detachment, presenting him with a note which stated

On Oct 9, 1944, Pvt Eddie D. Slovik deserted from his infantry unit. His friend, John Tankey, caught up with him and attempted to persuade him to stay, but Slovik’s only comment was that his mind was made up. Slovik walked several miles to the rear and approached an enlisted cook at a Hqs detachment, presenting him with a note which stated

I, Pvt Eddie D. Slovik, ASN 36896415, confess to the desertion of the United States Army. At the time of my desertion we were in Elbeuf, France. I came to Elbeuf as a replacement. They were shelling the town and we were told to dig in for the night. The following morning they were shelling us again. I was so scared, nerves and trembling, that at the time the other replacements moved out, I couldn’t move. I stayed there in my foxhole till it was quiet and I was able to move. I then walked into town. Not seeing any of our troops, so I stayed over night at a French hospital. The next morning I turned myself over to the Canadian Provost Corp. After being with them six weeks I was turned over to American MP. They turned me loose. I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out there again I’d run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again and I will run again is I have to go out there.

Eddie D. Slovik (ASN 36896415) (Feb 18, 1920 – Jan 31, 1945) was a United States Army soldier during World War II and the only American soldier to be court-martialled and executed for desertion since the American Civil War. Although over 21.000 American soldiers were given varying sentences for desertion during World War II, including forty-nine death sentences, Slovik’s death sentence was the only one that was carried out. During World War II, 1.7 million courts-martial were held, representing one third of all criminal cases tried in the United States during the same period. Most of the cases were minor, as were the sentences. Nevertheless, a clemency board, appointed by the Secretary of War in the summer of 1945, reviewed all general courts-martial where the accused was still in confinement, and remitted or reduced the sentence in 85 percent of the 27.000 serious cases reviewed. The death penalty was rarely imposed, and those cases were for rapes or murders. Slovik was the only soldier executed who had been convicted of a ‘purely military’ offense.

(NB) More info on Eddie Slovick : he was a career criminal who deserted and refused to rejoin his unit well before he got near any fighting because he thought he’d be punished by only imprisonment, something he was well familiar with. He did not have shell-shock, PTSD or any other extenuating circumstances. As much as his execution was unusual, the vast majority of troops agreed with it, primarily because they felt deserters were selfishly dumping danger and death on them. Troops lived in a harsh reality so different to the safe world of those keen to air their conscience.

(NB) More info on Eddie Slovick : he was a career criminal who deserted and refused to rejoin his unit well before he got near any fighting because he thought he’d be punished by only imprisonment, something he was well familiar with. He did not have shell-shock, PTSD or any other extenuating circumstances. As much as his execution was unusual, the vast majority of troops agreed with it, primarily because they felt deserters were selfishly dumping danger and death on them. Troops lived in a harsh reality so different to the safe world of those keen to air their conscience.

The 28-ID was scheduled to begin an attack in the Hürtgen Forest. The coming attack was common knowledge in the unit, and casualty rates were expected to be high, as the prolonged combat in the area had been unusually grueling. The Germans were determined to hold. Terrain and weather greatly reduced the usual American advantages in armor and air support. A small minority of soldiers (less than 0.5%) indicated they preferred to be imprisoned rather than remain in combat, and the rates of desertion and other crimes had begun to rise. Slovik is an example. He was charged with desertion to avoid hazardous duty and tried by court martial on Nov 11, 1944. Slovik had to be tried by a court martial composed of staff officers from other US Army divisions, because all combat officers from the 28-ID were fighting on the front lines. The prosecutor, Capt John Green, presented witnesses to whom Slovik had stated his intention to run away. The defense counsel, Capt Edward Woods, announced that Slovik had elected not to testify. At the end of the day, the nine officers of the court found Slovik guilty and sentenced him to death. The sentence was reviewed and approved by the division commander, Gen Norman Cota. Gen Cota’s stated attitude was

The 28-ID was scheduled to begin an attack in the Hürtgen Forest. The coming attack was common knowledge in the unit, and casualty rates were expected to be high, as the prolonged combat in the area had been unusually grueling. The Germans were determined to hold. Terrain and weather greatly reduced the usual American advantages in armor and air support. A small minority of soldiers (less than 0.5%) indicated they preferred to be imprisoned rather than remain in combat, and the rates of desertion and other crimes had begun to rise. Slovik is an example. He was charged with desertion to avoid hazardous duty and tried by court martial on Nov 11, 1944. Slovik had to be tried by a court martial composed of staff officers from other US Army divisions, because all combat officers from the 28-ID were fighting on the front lines. The prosecutor, Capt John Green, presented witnesses to whom Slovik had stated his intention to run away. The defense counsel, Capt Edward Woods, announced that Slovik had elected not to testify. At the end of the day, the nine officers of the court found Slovik guilty and sentenced him to death. The sentence was reviewed and approved by the division commander, Gen Norman Cota. Gen Cota’s stated attitude was

Given the situation as I knew it in Nov 1944, I thought it was my duty to this country to approve that sentence. If I hadn’t approved it, if I had let Slovik accomplish his purpose, I don’t know how I could have gone up to the line and looked a good soldier in the face.

On Dec 9, Slovik wrote a letter to the Supreme Allied commander, Gen Dwight D. Eisenhower, pleading for clemency. However, desertion had become a systemic problem in France, and the surprise German offensive through the Ardennes began on Dec 16 with severe US casualties, pocketing several battalions and straining the morale of the infantry to the greatest extent yet seen during the war. Ike confirmed the execution order on Dec 23, noting that it was necessary to discourage further desertions. The sentence came as a shock to Slovik, who had expected a dishonorable discharge and a jail term (the latter of which he assumed would be commuted once the war was over), the same punishment he had seen meted out to other deserters from the division while he was confined to the stockade. The execution by firing squad was carried out at 1004 on Jan 31, 1945, near the village of Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines. The unrepentant Slovik said to the soldiers whose duty it was to prepare him for the firing squad before they led him to the place of execution, they’re not shooting me for deserting the United States Army, thousands of guys have done that. They just need to make an example out of somebody and I’m it because I’m an ex-con. I used to steal things when I was a kid, and that’s what they are shooting me for. They’re shooting me for the bread and chewing gum I stole when I was 12 years old.

On Dec 9, Slovik wrote a letter to the Supreme Allied commander, Gen Dwight D. Eisenhower, pleading for clemency. However, desertion had become a systemic problem in France, and the surprise German offensive through the Ardennes began on Dec 16 with severe US casualties, pocketing several battalions and straining the morale of the infantry to the greatest extent yet seen during the war. Ike confirmed the execution order on Dec 23, noting that it was necessary to discourage further desertions. The sentence came as a shock to Slovik, who had expected a dishonorable discharge and a jail term (the latter of which he assumed would be commuted once the war was over), the same punishment he had seen meted out to other deserters from the division while he was confined to the stockade. The execution by firing squad was carried out at 1004 on Jan 31, 1945, near the village of Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines. The unrepentant Slovik said to the soldiers whose duty it was to prepare him for the firing squad before they led him to the place of execution, they’re not shooting me for deserting the United States Army, thousands of guys have done that. They just need to make an example out of somebody and I’m it because I’m an ex-con. I used to steal things when I was a kid, and that’s what they are shooting me for. They’re shooting me for the bread and chewing gum I stole when I was 12 years old.

Wearing an uniform stripped of all insignia with a GI blanket across his shoulders against the cold, Slovik was led into the courtyard of a house chosen for the execution because it had a high masonry wall. The commanders did not want the local French civilians to witness the proceedings. Soldiers stood him against a six inch by six inch post. The soldiers strapped him to the post using web belts. One went around and under his arms and hung on a spike on the back side of the post to prevent his body from slumping following the volley. The others went around his knees and ankles. Just before a soldier placed a black hood over his head, the attending chaplain said to Slovik, Eddie, when you get up there, say a little prayer for me. Slovik answered, Okay, Father. I’ll pray that you don’t follow me too soon. Those were his last words. Twelve picked soldiers were detailed for the firing squad from the 109-IR. The weapons used were standard issue M-1 rifles with just one bullet for each rifle. One rifle was loaded with a blank. On the command of Fire, Slovik was hit by eleven bullets, at least four of them being fatal. The wounds ranged from high in the neck region out to the left shoulder, over the left chest, and under the heart. One bullet was in the left upper arm. An Army physician quickly determined Slovik had not been immediately killed. Just as the firing squad’s rifles were being reloaded in preparation for another volley, but before the reloading of the rifles was complete, Pvt Slovik died. He was 24 years of age. The whole process took 15 minutes.

Having lost much of its offensive punch, the mission of the 28-ID now turned to the defensive. Initially the 28-ID dug-in and defended the ground that it had gained at such a high cost. Units then conducted operations to eliminate bypassed pockets of enemy troops that remained in the division rear. The 112-RCT remained on detached service with the 5-AD until early October. While operations continued on this reduced scale, the 28-ID was also integrating large numbers of replacements into its 27 rifle companies. During September, the division received 3352 replacements, or an average of more than 100 replacements for each rifle company. This figure equated to roughly 50 percent of the company’s strength. September ended with the 28-ID engaged in efforts to rebuild its battered units. The month had been a bitter one for the division. Its failure to breach the Siegfried Line was a hard one for the division to accept. As the soldiers stared across at the German line of fortifications, they realized that the enemy positions grew stronger each day. They also realized that they would soon have to launch a new assault to penetrate those defenses. It was a sobering thought after the heady days of August, when enemy resistance melted before the American advance. The 28-ID faced a new enemy now. This enemy might consist of cooks, youngsters, and grandfathers, but they were fighting on their home soil and enjoyed the advantage of prepared defenses. As the loss of Fox Co 110-IR demonstrated, there was also a hard core remaining of the fighting force that had conquered much of Europe. As the cold rains of September fell on the soldiers, there must surely have been those who realized they were in for a very long and very tough winter.

Having lost much of its offensive punch, the mission of the 28-ID now turned to the defensive. Initially the 28-ID dug-in and defended the ground that it had gained at such a high cost. Units then conducted operations to eliminate bypassed pockets of enemy troops that remained in the division rear. The 112-RCT remained on detached service with the 5-AD until early October. While operations continued on this reduced scale, the 28-ID was also integrating large numbers of replacements into its 27 rifle companies. During September, the division received 3352 replacements, or an average of more than 100 replacements for each rifle company. This figure equated to roughly 50 percent of the company’s strength. September ended with the 28-ID engaged in efforts to rebuild its battered units. The month had been a bitter one for the division. Its failure to breach the Siegfried Line was a hard one for the division to accept. As the soldiers stared across at the German line of fortifications, they realized that the enemy positions grew stronger each day. They also realized that they would soon have to launch a new assault to penetrate those defenses. It was a sobering thought after the heady days of August, when enemy resistance melted before the American advance. The 28-ID faced a new enemy now. This enemy might consist of cooks, youngsters, and grandfathers, but they were fighting on their home soil and enjoyed the advantage of prepared defenses. As the loss of Fox Co 110-IR demonstrated, there was also a hard core remaining of the fighting force that had conquered much of Europe. As the cold rains of September fell on the soldiers, there must surely have been those who realized they were in for a very long and very tough winter.

The Quiet Time

During the month of October, the Keystone Division enjoyed its first significant period of rest since its arrival on the continent in July. Occupying new defensive positions east of the Belgian town of Elsenborn, the division was able to rotate battalions to quiet rear areas for training, rest, and recreation. Due to the large numbers of replacements and their generally poor performance during September’s fighting, the V Corps published a detailed training program. The designated training priorities included: assault of a fortified position, river crossing techniques, personal hygiene for winter months, patrolling, booby trap removal, defensive positions, and weapons familiarization. The V Corps also noted significant weaknesses in the confidence and morale of replacements. Concern over this problem was such that the corps developed a unique arrangement with the headquarters tasked to provide combat replacements, the Ground Forces Replacement Command.

Under this arrangement, the forward replacement companies identified replacements for future assignment to a specific division. These soldiers were then temporarily attached to that division for training. Their exposure to seasoned veterans was supposed to help allay the fear of the unknown that plagued so many of the replacements. At the end of a week the replacements returned to their holding company, hopefully with better soldier skills, improved morale, and a strong attachment to their future division. It is unknown how many of these replacements actually went to their designated units, but 250 of these soldiers would figure prominently in future combat with the 28-ID. It was however, a worthwhile effort at improving the morale and training of future replacements.

Under this arrangement, the forward replacement companies identified replacements for future assignment to a specific division. These soldiers were then temporarily attached to that division for training. Their exposure to seasoned veterans was supposed to help allay the fear of the unknown that plagued so many of the replacements. At the end of a week the replacements returned to their holding company, hopefully with better soldier skills, improved morale, and a strong attachment to their future division. It is unknown how many of these replacements actually went to their designated units, but 250 of these soldiers would figure prominently in future combat with the 28-ID. It was however, a worthwhile effort at improving the morale and training of future replacements.

The rest and recreation opportunities available to soldiers during this period were extremely limited. The V Corps directed the establishment of a corps rest center, but this facility was not operational until the end of October. Furloughs for soldiers to facilities further in the rear, such as those in Paris, were also not available until late in the month. For the most part, the burden was on the combat units to establish some form of rest facility. This was difficult for divisions, given their limited support assets, and was especially difficult when the division remained engaged in even limited combat operations. At this stage in the war, division rest facilities were practically non-existent. Instead, the regiments rotated battalions out of the line for rest and training. In a quiet sector regiments normally defended with two battalions forward and one battalion in an assembly area. The battalions periodically rotated between the forward positions and the assembly area. If the unit’s frontage was not too excessive, the forward battalions might even rotate companies to a reserve position where soldiers might rest and train. In the assembly area the battalion could train, provide frequent hot meals, and allow soldiers to catch up on sleep and letter writing.

Whenever possible, the regiment located the assembly area in a town that could provide warm, dry houses for soldiers to sleep in. While certainly limited in what they could provide, these rest facilities did much for the health and morale of soldiers. Surveys and interviews of soldiers indicated that facilities such as those described were wonderful tools for maintaining morale. If a unit was lucky it might have access to a Red Cross caravan in its rest area. These caravans were one of the most highly regarded services available to front-line divisions. An odd collection of military and civilian vehicles, it included doughnut and coffee making equipment, games, phonographs, and movie projectors. On a rotating basis these club mobiles, as the Red Cross called them, set up in a division’s rear area. Even during the race across France the Red Cross was able to catch up and provide services for soldiers.

Whenever possible, the regiment located the assembly area in a town that could provide warm, dry houses for soldiers to sleep in. While certainly limited in what they could provide, these rest facilities did much for the health and morale of soldiers. Surveys and interviews of soldiers indicated that facilities such as those described were wonderful tools for maintaining morale. If a unit was lucky it might have access to a Red Cross caravan in its rest area. These caravans were one of the most highly regarded services available to front-line divisions. An odd collection of military and civilian vehicles, it included doughnut and coffee making equipment, games, phonographs, and movie projectors. On a rotating basis these club mobiles, as the Red Cross called them, set up in a division’s rear area. Even during the race across France the Red Cross was able to catch up and provide services for soldiers.

During the months of September and October, these facilities produced more than 350.000 doughnuts for V Corps soldiers and served 140.000 cups of coffee. On few occasions was a regular infantry division able to enjoy the luxury of being pulled completely out of the line. There were simply too few divisions available for this to occur.

During the months of September and October, these facilities produced more than 350.000 doughnuts for V Corps soldiers and served 140.000 cups of coffee. On few occasions was a regular infantry division able to enjoy the luxury of being pulled completely out of the line. There were simply too few divisions available for this to occur.

At the beginning of October, there were only 24 infantry divisions and six armored divisions actually available for combat in the ETO. The British Army forces added an additional 18, the French contributed eight divisions, and the Polish Army one division. These 57 divisions were arrayed along a front that stretched from the North Sea south to the Swiss border, a distance of over 500 miles. Only the airborne divisions enjoyed the luxury of moving to secure rear areas for reorganization, rest, and training. Instead, infantry divisions that need to rebuild moved to defensive sectors located in supposedly quiet and inactive areas. These quiet sectors were not without hazards. The cost to the 28-ID during its month of rest in October included 59 soldiers killed, 519 wounded, and 433 non-battle casualties.

These quiet sectors did provide opportunities for green soldiers to gain valuable combat experience. Participating in small unit patrols was considered very beneficial for new soldiers. Contact during these patrols was generally very light, although there were exceptions. Normally these exceptions resulted when a patrol was careless and the enemy reacted with artillery and mortar fire. These patrols were also of great value to newly assigned leaders. Under the watchful eyes of an experienced leader, new officers and NCOs were able gain an appreciation for the terrain and also gain confidence in their ability to lead.

On October 25, the 28-ID boarded trucks and began movement north to a new assembly area in the vicinity of Roetgen, Germany. The division had orders to relieve the 9-ID and prepare to conduct an attack to seize objectives in the vicinity of Schmidt. During October, the division received more than 1400 replacements, only 124 of which were RTD soldiers. At the end of the month the 28 had 13.997 soldiers present for duty, a shortage of approximately 250 personnel. The division had been able to conduct limited training to integrate the large numbers of replacements received during September and October. Many veterans had also been able to enjoy a brief respite from combat. Poor weather during the period did much to cancel the positive influence of the rest period. The rains of September continued into October and temperatures steadily declined. Most soldiers in the division, particularly the veterans, still lacked winter clothing and over-boots. Trenchfoot cases though, remained relatively low, due most likely to the tactical situation which allowed frequent rotation of soldiers to warming shelters. Overall, after almost a month of quiet duty, the division was able to report its combat status to V Corps as excellent.

On October 25, the 28-ID boarded trucks and began movement north to a new assembly area in the vicinity of Roetgen, Germany. The division had orders to relieve the 9-ID and prepare to conduct an attack to seize objectives in the vicinity of Schmidt. During October, the division received more than 1400 replacements, only 124 of which were RTD soldiers. At the end of the month the 28 had 13.997 soldiers present for duty, a shortage of approximately 250 personnel. The division had been able to conduct limited training to integrate the large numbers of replacements received during September and October. Many veterans had also been able to enjoy a brief respite from combat. Poor weather during the period did much to cancel the positive influence of the rest period. The rains of September continued into October and temperatures steadily declined. Most soldiers in the division, particularly the veterans, still lacked winter clothing and over-boots. Trenchfoot cases though, remained relatively low, due most likely to the tactical situation which allowed frequent rotation of soldiers to warming shelters. Overall, after almost a month of quiet duty, the division was able to report its combat status to V Corps as excellent.

The 28-ID completed the relief of the 9-ID on Oct 27. Moving in to the 9-ID sector was an horrifying experience for the soldiers of the 28-ID, particularly for the large number of soldiers without combat experience. The terrain was thickly forested and artillery had slashed trees into a variety of strange and frightening shapes. Scattered throughout the sector were the bodies of soldiers from the 9-ID. The heavy losses and difficult terrain completely overwhelmed graves registration personnel. Discarded equipment and trash lay everywhere. The ragged and shattered appearance of the soldiers of the 9-ID also had a big impact on the 28-ID. The rumors of the heavy fighting in this sector of the front were proving true to the soldiers of the Division. The popular nickname for this portion of the war was the Green Hell. The official unit history recorded the battle as the Hürtgen Forest Campaign.

The 28-ID completed the relief of the 9-ID on Oct 27. Moving in to the 9-ID sector was an horrifying experience for the soldiers of the 28-ID, particularly for the large number of soldiers without combat experience. The terrain was thickly forested and artillery had slashed trees into a variety of strange and frightening shapes. Scattered throughout the sector were the bodies of soldiers from the 9-ID. The heavy losses and difficult terrain completely overwhelmed graves registration personnel. Discarded equipment and trash lay everywhere. The ragged and shattered appearance of the soldiers of the 9-ID also had a big impact on the 28-ID. The rumors of the heavy fighting in this sector of the front were proving true to the soldiers of the Division. The popular nickname for this portion of the war was the Green Hell. The official unit history recorded the battle as the Hürtgen Forest Campaign.

The Hürtgen Forest, as the entire area became known, embraced a thickly wooded section of Germany approximately 50 square miles in size. The forest consisted primarily of fir trees, planted so closely together that a man often had to crawl to get through them. Sunlight had a tough time penetrating through the trees and observers described the area as dark and forbidding. As units advanced in the forest, the separation and isolation of individual soldiers was significant. In some areas it was possible to see only the man to your immediate front or flank. Navigation was difficult to impossible for many units.

Numerous ravines, some quite large, such as the Kall River Gorge, cut the ground and blocked almost all movement. Roads and trails, the few that existed, were deep in mud. Moving supplies forward over these paths proved to be a major challenge. There were few battles in the ETO in which terrain had such an overwhelming physical and psychological effects on soldiers and units as did the Huertgen Forest. The enemy defenses were equally formidable, though soldiers in this sector were certainly not Germany’s finest. For the most part they were the very young, the very old, and the infirm. A cadre of combat veterans provided the backbone for the units. Their defensive fighting power in this terrain was formidable and American soldiers were to learn a tough lesson about the effectiveness of well-led soldiers fighting from prepared defenses. The Germans fought from camouflaged bunkers that had excellent interlocking fields of fire. The fires of automatic weapons extracted a heavy price from anyone that moved on the existing trails and firebreaks. The Germans planted thousands of mines in the area; many designed not to kill, but to maim instead. One mine, the S-Mine (Schrapnellmine, Springmine or Splittermine) and nicknamed Bouncing Betty by the US troops was notorious for amputating legs and the male genitals.

Numerous ravines, some quite large, such as the Kall River Gorge, cut the ground and blocked almost all movement. Roads and trails, the few that existed, were deep in mud. Moving supplies forward over these paths proved to be a major challenge. There were few battles in the ETO in which terrain had such an overwhelming physical and psychological effects on soldiers and units as did the Huertgen Forest. The enemy defenses were equally formidable, though soldiers in this sector were certainly not Germany’s finest. For the most part they were the very young, the very old, and the infirm. A cadre of combat veterans provided the backbone for the units. Their defensive fighting power in this terrain was formidable and American soldiers were to learn a tough lesson about the effectiveness of well-led soldiers fighting from prepared defenses. The Germans fought from camouflaged bunkers that had excellent interlocking fields of fire. The fires of automatic weapons extracted a heavy price from anyone that moved on the existing trails and firebreaks. The Germans planted thousands of mines in the area; many designed not to kill, but to maim instead. One mine, the S-Mine (Schrapnellmine, Springmine or Splittermine) and nicknamed Bouncing Betty by the US troops was notorious for amputating legs and the male genitals.

Artillery and mortars, though much smaller in numbers than those possessed by the Americans, were lethal and effective. The thick evergreens turned many of the rounds into devastating air bursts. Soldiers learned quickly that lying prone on the ground while receiving artillery fire was the worst possible thing to do. Instead, soldiers learned to crouch or stand close against a tree, minimizing the bodily surface area they exposed to the blasts.

The S-Minen, also known as ‘Bouncing Betty’, is the best-known version of a class of mines known as bouncing mines. When triggered, these mines launch into the air and then detonate at about 0.9 meter (3 ft).

The explosion projects a lethal spray of shrapnel in all directions. The S-Mine was an anti-personnel mine developed by Germany in the 1930s and used extensively by German forces during World War II. It was designed to be used in open areas against unshielded infantry. Two versions were produced, designated by the year of their first production: the SMi-35 and SMi-44. There are only minor differences between the two models. The S-mine entered production in 1935 and served as a key part of the defensive strategy of the Third Reich. Until production ceased in 1945, Germany produced over 1.93 million S-mines. These mines inflicted heavy casualties and slowed, or even repelled, drives into German-held territory throughout the war. The design was lethal, successful and much imitated. The S-mine remains one of the definitive weapons of WW-2.

The explosion projects a lethal spray of shrapnel in all directions. The S-Mine was an anti-personnel mine developed by Germany in the 1930s and used extensively by German forces during World War II. It was designed to be used in open areas against unshielded infantry. Two versions were produced, designated by the year of their first production: the SMi-35 and SMi-44. There are only minor differences between the two models. The S-mine entered production in 1935 and served as a key part of the defensive strategy of the Third Reich. Until production ceased in 1945, Germany produced over 1.93 million S-mines. These mines inflicted heavy casualties and slowed, or even repelled, drives into German-held territory throughout the war. The design was lethal, successful and much imitated. The S-mine remains one of the definitive weapons of WW-2.

To make matters worse for the 28-ID, a fresh enemy division, Oberst Georg Koßmala’s 272.Volksgrenadier-Division was in the process of relieving Gen Walter Bruns’ 89.Infantry-Division in the sector. An additional German division, Gen Siegfried von Waldenburg’s 116.Panzer-Division, was also in a position to counterattack the 28-ID. This meant that the 28-ID would face elements of up to four divisions during its attack in the forest. It was small consolation that most of the German units were badly under-strength. Given the harshness of the terrain, this was a formidable defensive force. The combined effects of the enemy and terrain created one of the most difficult barriers an attacking force could ever hope to encounter.

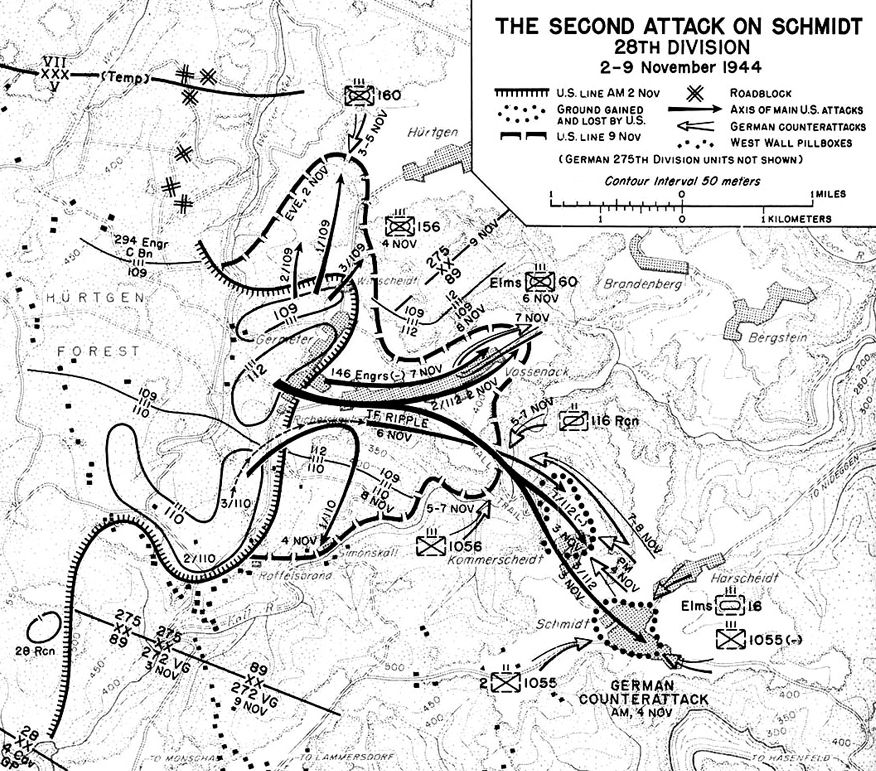

The withdrawing of the 9-ID endured almost two months of heavy fighting in this frightful landscape and suffered more than 4500 casualties. The division had little to show for its efforts. It had captured few of its assigned objectives and penetrated the forest to a depth of only 3000 meters. This was a best effort from one of the most highly regarded infantry divisions in the US Army. Before the fighting ended in the Hürtgen Forest, eight American infantry divisions would fight in this area. The average casualty total per division was more than 4000 men. The 28-ID would fare worse than any of them. The Keystone Division launched its attack on the early morning hours of Nov 2. A massive artillery barrage, one hour in duration, preceded the attack. Division and Corps artillery units fired almost 12.000 rounds in support of the 28-ID. Fighter aircraft were scheduled to support the troops, but poor weather limited their employment. Given the difficult terrain, the first day of the attack started well for the division. Two regiments, the 109-IR and the 112-IR, enjoyed mixed success, seizing portions of their assigned objectives and then digging-in for the night with only light casualties.

The 110-IR, attacking in the south, met very stiff resistance. Casualties were heavy for the regiment and by nightfall it was fighting to hold onto its original start-line for the attack. Some rifle companies lost almost two-thirds of their strength on that very first day. The second day of the operation was an enormous success. The 3/112 launched its attack at 0700, advanced swiftly against light resistance, and by 1430 captured the town of Schmidt, the division’s primary objective. The 9-ID had fought unsuccessfully for weeks to capture this town. A state of euphoria swept the division and corps headquarters. Unfortunately, the 3/112 was the only unit from the 112-IR that reached Schmidt on Nov 3. The battalion was also without armor support. The only route into Schmidt open to the division was the Kall Trail and this route was proving to be nearly impassable for armor. The 3/112 was dangerously exposed and its only anti-tank weapons were mines and bazookas.

Its soldiers were also cold, wet, and exhausted. Leaders and soldiers alike sought out warm buildings during the night and prepared only the most rudimentary of defenses. The battalion sent out no patrols during the night and as a result, the commander was blind to what was around his unit. The 109-IR and the 110-IR made no progress on Nov 3. In the south, tough German defenses continued to hold the 110-IR in check. Casualties for the regiment mounted steadily. The infantry units, unsupported by tanks, continued to force the assault despite the heavy casualties. By the end of the day, they still had nothing to show for their sacrifices. In the north the initial success of the 109-IR also ground to a halt. At dawn the 109-IR fought off two counter-attacks and subsequently canceled plans for its own attack toward the town of Hürtgen. Much like the forward elements of the 112-IR, the 109-IR found itself surrounded on three sides by well dug-in defenders.

Its soldiers were also cold, wet, and exhausted. Leaders and soldiers alike sought out warm buildings during the night and prepared only the most rudimentary of defenses. The battalion sent out no patrols during the night and as a result, the commander was blind to what was around his unit. The 109-IR and the 110-IR made no progress on Nov 3. In the south, tough German defenses continued to hold the 110-IR in check. Casualties for the regiment mounted steadily. The infantry units, unsupported by tanks, continued to force the assault despite the heavy casualties. By the end of the day, they still had nothing to show for their sacrifices. In the north the initial success of the 109-IR also ground to a halt. At dawn the 109-IR fought off two counter-attacks and subsequently canceled plans for its own attack toward the town of Hürtgen. Much like the forward elements of the 112-IR, the 109-IR found itself surrounded on three sides by well dug-in defenders.

Disaster struck the 28-ID during the early morning hours of Nov 4. A strong German counter-attack composed of armor from the 116.Panzer-Division and infantry forces from the 89.Infantry-Division struck the 3/112 in Schmidt just after dawn. German artillery conducted a brief but fierce shelling of the town immediately prior to the German assault. The shelling stunned the American infantry in their hastily prepared positions. The German infantry made good use of the artillery barrage and attacked the town from almost every angle. German tanks, impervious to the rifle and bazooka fire of the American infantrymen, followed close on the heels of the attacking infantry. Due to communications difficulties the American artillery did not begin to provide support until the German attack was over an hour old. Confusion within the 3/112 grew rapidly and soon turned into panic. Soldiers began to flee for the woods and leaders lost all semblance of control. In little more than three hours of fighting the Germans recaptured Schmidt and the 3/112 ceased to exist as an effective combat force.