The German counter-attack next struck the 1/112, defending the village of Kommerscheidt. Here the American defenses were better prepared and had armor support in the form of three Sherman tanks. Leaders also rounded up and put into the line approximately 200 of the panic-stricken soldiers from Schmidt. The defenders beat back the German attack, though not without substantial losses. Early the next morning, 9 tank destroyers and 6 medium tanks further reinforced the position at Kommerscheidt. This discouraged any immediate German efforts to launch another counter-attack.

The German counter-attack next struck the 1/112, defending the village of Kommerscheidt. Here the American defenses were better prepared and had armor support in the form of three Sherman tanks. Leaders also rounded up and put into the line approximately 200 of the panic-stricken soldiers from Schmidt. The defenders beat back the German attack, though not without substantial losses. Early the next morning, 9 tank destroyers and 6 medium tanks further reinforced the position at Kommerscheidt. This discouraged any immediate German efforts to launch another counter-attack.

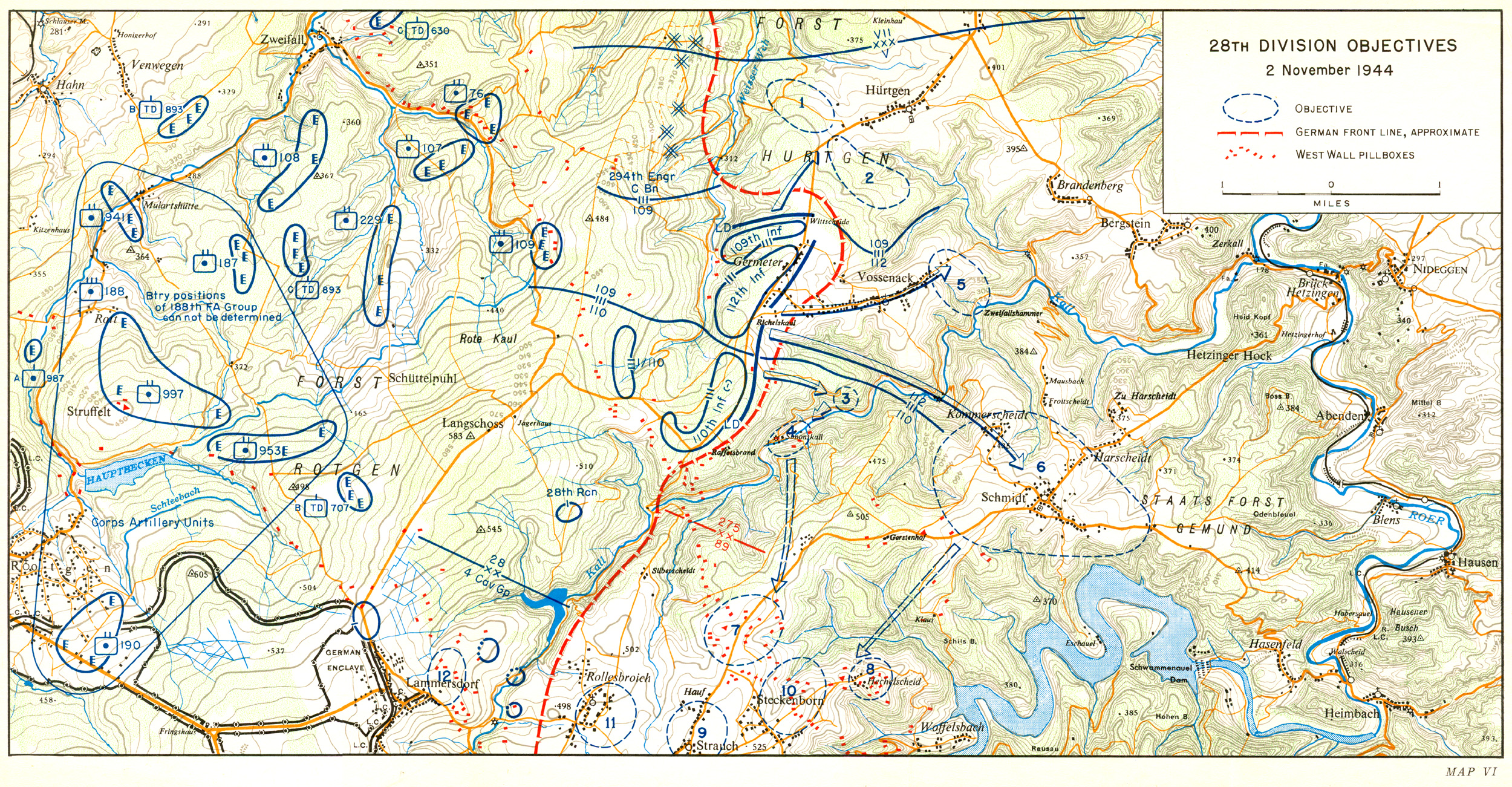

Fighting, on Nov 5 and 6, took on a confusing and fragmented pattern. Small unit engagements occurred in the zones of all three regiments. The 110-IR had settled into a battle of attrition with the enemy. Progress was impossible given the ferocity of the enemy resistance, the well-positioned obstacles, and the difficult nature of the terrain. Soldiers of the regiment dug-in almost within hand grenade range of the enemy. Each day they received new orders to attack and each day leaders forced men from their holes. Within minutes, the advance would be halted and soldiers would return to their cold, wet foxholes. Such persistence almost completely shattered the offensive capability of the 110-IR. In the north, the 109-IR was also subjected to strong German pressure, but managed to hold on to its positions. In this portion of the forest, it was difficult for the Germans to support their attacks with armor. The lesson for both forces was that even in this restrictive terrain, attacks without armor support had little chance of success.

The Germans managed to briefly cut the only supply route into Kommerscheidt, but a small American task force of armor and infantry reopened the Kall Trail on the morning of Nov 6.

The Germans managed to briefly cut the only supply route into Kommerscheidt, but a small American task force of armor and infantry reopened the Kall Trail on the morning of Nov 6.

The situation for the 28-ID was growing worse by the hour. By now the regiments discarded all thought of further offensive operations, they were instead fighting for their lives. Incredibly, the division continued to order units to attack, few of which complied. Many of the infantry companies were now well below 50 percent strength. The 28-ID had lost all offensive capability and was fighting to survive. The division began to push replacements forward; at the head of the line were the 250 soldiers that the division trained in October. Brought forward during the night, these frightened and inexperienced soldiers were put into foxholes with little or no training. As an example, on Nov 8, the 2/112, with an authorized strength of approximately 850, received 515 replacements. Even more incredibly, the battalion received the mission to attack on the following morning. It was impossible for any unit to accept such large numbers of replacements and remain an effective force. For the unfortunate replacements it was almost a case of murder. Many of them would be evacuated at each sunrise, victims of trench-foot, battle fatigue or enemy fire.

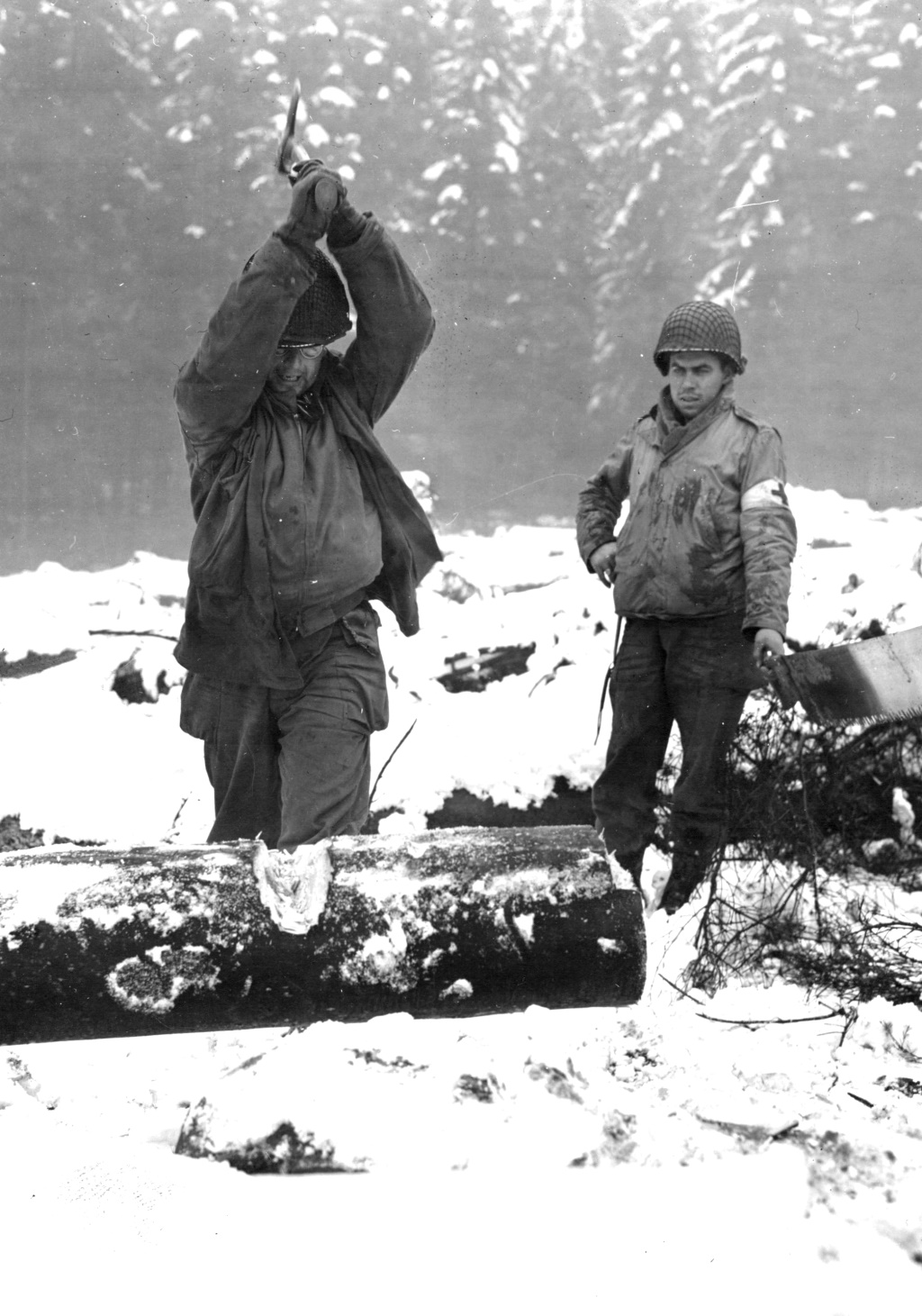

The enemy was not the only source of casualties within the 28-ID. The cold and wet weather, with temperatures hovering around freezing, took a terrible toll on soldiers. Trench-foot and respiratory infection cases skyrocketed. Many soldiers were still without necessary cold weather clothing items such as overshoes, field jackets, woolen caps, and long underwear. The continual lack of hot rations also damaged the health and morale of soldiers. Rations consisted of cold K-Rations or C-Rations and many soldiers ceased eating. The situation was much too dangerous to risk bringing hot meals or drinks forward. The soldiers were also unable to build fires, since their proximity to the enemy was sure to draw rifle and mortar fire. Less than a week into the operation the division was virtually worn out as a fighting force. On the morning of Nov 6, another infantry battalion collapsed. This time it was the 2/112, defending an exposed position along a ridge near the town of Vossenack. The battalion had been subjected to almost continuous fire from German artillery for three days. Soldiers, most of them green replacements, had become so demoralized that leaders had to force them to eat and drink.

Finally, they were pushed beyond the breaking point. Imagining themselves about to be overrun, first one soldier, then another began to head for the rear. The panic became overpowering for many of the soldiers. The efforts of officers and NCOs could halt only a small percentage. There had been no German counter-attack, only blind panic. The 2/112 was left with only a thin line of resistance holding half of the town. An engineer battalion rushed in to bolster the defenses. The next morning the engineers attacked and within hours cleared the remainder of Vossenack of German resistance.

The next day the Germans struck the 1/112 in Kommerscheidt, protected from air attack by a steady winter rain. The defenders held firm initially, but gradually began to pull back under the weight of the German attack. The 1/112 conducted its withdrawal in good order and managed to reestablish a weak defensive line just outside the town. The panic that afflicted the other two battalions of the 112-IR did not occur in Kommerscheidt. Nevertheless, by the end of the day, the defenders had been pushed from the town. The following day, this small group of infantry and armor, along with other scattered elements still on the east side of the Kall River, withdrew to the west bank. This withdrawal effectively ended offensive operations for the division. The division ordered further attacks in the zones of the 109-IR and the 110-IR. The units executed the attacks with little determination and achieved nothing except to add to the division’s casualty totals.

The next day the Germans struck the 1/112 in Kommerscheidt, protected from air attack by a steady winter rain. The defenders held firm initially, but gradually began to pull back under the weight of the German attack. The 1/112 conducted its withdrawal in good order and managed to reestablish a weak defensive line just outside the town. The panic that afflicted the other two battalions of the 112-IR did not occur in Kommerscheidt. Nevertheless, by the end of the day, the defenders had been pushed from the town. The following day, this small group of infantry and armor, along with other scattered elements still on the east side of the Kall River, withdrew to the west bank. This withdrawal effectively ended offensive operations for the division. The division ordered further attacks in the zones of the 109-IR and the 110-IR. The units executed the attacks with little determination and achieved nothing except to add to the division’s casualty totals.

Finally, on Nov 14, the Hürtgen ordeal came to an end for the 28-ID. The 8-ID moved forward, relieved the Keystone Division and prepared to begin its own ordeal.

Finally, on Nov 14, the Hürtgen ordeal came to an end for the 28-ID. The 8-ID moved forward, relieved the Keystone Division and prepared to begin its own ordeal.  The 28-ID moved to a quiet sector 40 miles to the southwest and received the mission to defend a sector 25 miles in width. The division moved by truck and closed into the new sector by Nov 22. This quiet sector was located just to the east of the Belgian town of Bastogne. As units tallied up their losses the tremendous cost in lives became obvious. Division combat casualties totaled 6184, a figure that exceeded the total strength of every rifle company in the division. Losses included 614 killed, 2605 wounded, 855 missing, 245 captured, and 1865 non-battle casualties. More than 750 of the non-battle casualties were from trench-foot alone.

The 28-ID moved to a quiet sector 40 miles to the southwest and received the mission to defend a sector 25 miles in width. The division moved by truck and closed into the new sector by Nov 22. This quiet sector was located just to the east of the Belgian town of Bastogne. As units tallied up their losses the tremendous cost in lives became obvious. Division combat casualties totaled 6184, a figure that exceeded the total strength of every rifle company in the division. Losses included 614 killed, 2605 wounded, 855 missing, 245 captured, and 1865 non-battle casualties. More than 750 of the non-battle casualties were from trench-foot alone.

The fighting proved to be one of the costliest division operations of the entire war. To make matters worse, the leadership of the rifle units continued to absorb terrible losses. Officer losses alone totaled 249 out of an assigned officer strength of 828, roughly one officer in three. Losses among NCOs were not specified, but were probably as bad or worse.

Many of the leader losses resulted from the poor fighting performance of soldiers. Significant numbers of replacements and even a few of the experienced soldiers lost almost all ability to fight. This required small unit leaders to constantly expose themselves to enemy fire as they moved among their men, trying to drive them forward. Losses were not limited to the leaders in rifle companies. One regimental commander and three of the nine battalion commanders in the division were also casualties.

Many of the leader losses resulted from the poor fighting performance of soldiers. Significant numbers of replacements and even a few of the experienced soldiers lost almost all ability to fight. This required small unit leaders to constantly expose themselves to enemy fire as they moved among their men, trying to drive them forward. Losses were not limited to the leaders in rifle companies. One regimental commander and three of the nine battalion commanders in the division were also casualties.

The two great unseen enemies of infantry divisions, battle fatigue and trench-foot, also contributed significantly to the casualty rate. Soldiers suffering from battle fatigue, primarily new personnel but with increasing numbers of veterans, lost all will to fight. In the worst cases, soldiers would not eat or perform even the basic functions of personal hygiene. In some cases unit leaders ordered the evacuation of battle fatigue victims, other victims simply wandered back through the lines to the nearest aid station. The problem started to surface during the Siegfried Line fighting, but became much worse in the Hürtgen Forest battle.

Based on its earlier experiences the division already had a special rest camp established for battle fatigue cases. Gen Cota directed the establishment of the rest center in August and staffed it despite the lack of TO&E resources. Like many senior officers he believed that a little rest, a hot meal, and a structured environment were the proper elements to restore a soldier to fighting trim. Trench-foot also contributed to enormous casualty rates. Although the rate of trench-foot cases did not approach the level of the First World War, it continued to have a destructive effect on infantry personnel.

From Oct 1944 to Apr 1945 there were more than 70.000 soldiers in the ETO hospitalized for trench-foot. More than 90 percent of the casualties were infantrymen. Less than 50 percent of these soldiers would ever return to combat duty. Many would spend long convalescent periods in stateside hospitals and amputation was not uncommon. Soldiers with trench-foot were normally out of action for several weeks to several months. A major cause of trench-foot in the 28-ID was a lack of adequate footwear and extra socks and most importantly a failure of leadership.

During the Hürtgen Forest Campaign only about 15 percent of soldiers had winter socks and overshoes. Many of the leaders were converted from other specialties such as anti-aircraft units and were fighting in their first battle.

1- Definition: Trench foot is a medical condition caused by prolonged exposure of the feet to damp, unsanitary, and cold conditions. It is one of many immersion foot syndromes. The use of the word trench in the name of this condition is a reference to trench warfare, mainly associated with World War I which started in 1914.

2- Characteristics: Affected feet may become numb, affected by erythrosis (turning red) or cyanosis (turning blue) as a result of poor vascular supply, and feet may begin to have a decaying odor due to the possibility of the early stages of necrosis setting in. As the condition worsens, feet may also begin to swell. Advanced trench foot often involves blisters and open sores, which lead to fungal infections; this is sometimes called tropical ulcer (jungle rot). If left untreated, trench foot usually results in gangrene, which can cause the need for amputation. If trench foot is treated properly, complete recovery is normal, though it is marked by severe short-term pain when feeling returns.

3- Causes: Unlike frostbite, trench foot does not require freezing temperatures and can occur in temperatures up to 16° Celsius (about 60° Fahrenheit). The condition can occur within as few as thirteen hours. The mechanism of tissue damage is not fully understood. Excessive sweating or hyperhidrosis has long been regarded as a contributory cause, also unsanitary, cold and wet conditions can cause Trench Foot.

3- Causes: Unlike frostbite, trench foot does not require freezing temperatures and can occur in temperatures up to 16° Celsius (about 60° Fahrenheit). The condition can occur within as few as thirteen hours. The mechanism of tissue damage is not fully understood. Excessive sweating or hyperhidrosis has long been regarded as a contributory cause, also unsanitary, cold and wet conditions can cause Trench Foot.

4- Prevention: Trench foot can be prevented by keeping the feet clean, warm, and dry. It was also discovered in World War I that a key preventive measure was regular foot inspections. Soldiers would be paired and each made responsible for the feet of the other. They would generally apply whale oil to prevent trench foot. If left to their own devices, soldiers might neglect to take off their own boots and socks to dry their feet each day, but if it were the responsibility of another this became less likely. Later on in the war, instances of trench foot began to decrease, probably as a result of the introduction of wooden duck-boards to cover the muddy, wet, cold ground of the trenches, and of the increased practice of troop rotation, which kept soldiers from prolonged time at the front.

5- History: Trench foot was first noted in Napoleon’s army in 1812. It was during the retreat from Russia that it became prevalent, and was first described by French army surgeon Dominique Jean Larrey. It was a particular problem for soldiers in trench warfare during the winters of World War I, World War II, and even later, during the Vietnam War. Trench foot made a reappearance in the British Army during the Falklands War in 1982. The causes were the cold, wet conditions and insufficiently waterproof DMS boots. Some people were even reported to have developed trench foot at the 1998 and 2007 Glastonbury Festivals, the 2009 and 2013 Leeds Festivals as well as the 2012 Download Festival, as a result of the sustained cold, wet, and muddy conditions at the events.

Even before the division closed into its new area of operations, the reconstitution process had begun. Replacements poured in at such a rate, that by the end of November the division stood at almost 100 percent strength. Elements of the 112-IR, the first unit to be pulled from action, moved to rear assembly areas, received new clothing and even, in some cases, weapons and ate their first hot meals in many days. When the division closed into its new sector, it repeated this process with the other units of the division. A few of the veteran soldiers received furloughs to visit Paris; others rotated through the newly established division rest center in Wiltz, Luxemburg. Rotation of troops between the line and regimental rest facilities also provided opportunities for soldiers to get hot meals, a shower, and a chance to sleep in a warm and dry bed. Gradually the strength of the 28-ID began to rebuild, although it would take some time to recover from the severe mauling it received in the Hürtgen Forest.

Even before the division closed into its new area of operations, the reconstitution process had begun. Replacements poured in at such a rate, that by the end of November the division stood at almost 100 percent strength. Elements of the 112-IR, the first unit to be pulled from action, moved to rear assembly areas, received new clothing and even, in some cases, weapons and ate their first hot meals in many days. When the division closed into its new sector, it repeated this process with the other units of the division. A few of the veteran soldiers received furloughs to visit Paris; others rotated through the newly established division rest center in Wiltz, Luxemburg. Rotation of troops between the line and regimental rest facilities also provided opportunities for soldiers to get hot meals, a shower, and a chance to sleep in a warm and dry bed. Gradually the strength of the 28-ID began to rebuild, although it would take some time to recover from the severe mauling it received in the Hürtgen Forest.

December found the Keystone Division still recovering from its wounds defending a 25 mile front along the Luxembourg – German border. Its assigned frontage was so great that units manned a series of strong points instead of a continuous line of resistance. These strong points generally controlled the major road networks in the sector. The strong points were, for the most part, built around the small villages and towns scattered throughout the sector. This positioning allowed units to rotate soldiers into shelters for rest, minimizing exposure to the tough winter conditions. Soldiers also continued to rotate to divisional and corps rest centers further to the rear. Red Cross club mobiles and doughnut wagons made their visits and there was a fill schedule of USO shows and dances to help raise moral. As units began to become effective organizations once more, training activities stepped up. Limited combat missions, primarily intelligence gathering patrols, remained excellent training vehicles to build the experience level of new soldiers and leaders.

Units also engaged in foot marches, techniques for assaulting bunkers, and basic infantry skills. The basic infantry skills training was particularly important, for by this time in the war a large number of the replacements were not infantrymen by training. The insatiable demand for infantry replacements forced the army to convert large numbers of specialty troops into riflemen. Two of the larger sources for such conversions were AAA units and the Army Air Force. The ETO also converted significant numbers of soldiers from the service troops in theater. Limited duty soldiers, soldiers who were no longer fit for combat due to medical reasons, took the place of the service troops.

A unique source of manpower was also beginning to show up in the replacement system during the latter part of 1944. These were soldiers from the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP). This program offered duty at a college or university for selected individuals that enlisted in the army. Its purpose was to attract high quality volunteers away from the Navy and Marines and was open only to soldiers that scored in the highest categories of mental ability. By 1944, the army could no longer afford to have so many soldiers unavailable for combat and made the decision to eliminate the program instead of sending these trainees to become officers, as many thought they would, they went instead into the general replacement pool. More than 70.000 ASTP trainees entered the replacement flow in 1944. There was even a special distribution plan to ensure that each infantry division received an equitable allocation of these potentially high caliber soldiers. Whatever their source, the replacements that joined the 28-ID in late 1944 were a cut above their predecessors. There was a noticeable rise in the quality of the 28th’s infantrymen. The German Army would soon provide them an opportunity to demonstrate their fighting abilities.

A unique source of manpower was also beginning to show up in the replacement system during the latter part of 1944. These were soldiers from the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP). This program offered duty at a college or university for selected individuals that enlisted in the army. Its purpose was to attract high quality volunteers away from the Navy and Marines and was open only to soldiers that scored in the highest categories of mental ability. By 1944, the army could no longer afford to have so many soldiers unavailable for combat and made the decision to eliminate the program instead of sending these trainees to become officers, as many thought they would, they went instead into the general replacement pool. More than 70.000 ASTP trainees entered the replacement flow in 1944. There was even a special distribution plan to ensure that each infantry division received an equitable allocation of these potentially high caliber soldiers. Whatever their source, the replacements that joined the 28-ID in late 1944 were a cut above their predecessors. There was a noticeable rise in the quality of the 28th’s infantrymen. The German Army would soon provide them an opportunity to demonstrate their fighting abilities.

Notable alumni of the ASTP include: Mel Brooks, American actor, filmmaker, and composer; Heywood Hale Broun, sports commentator; Frank Church, US Senator; Bill Dawson, prominent California attorney; Robert Dole, US Senator and Senate Majority Leader; Herman Kahn, futurist and theorist; Henry Kissinger, US Secretary of State, Nobel Prize winner; Ed Koch, US Congressman, New York City Mayor; George Koval, Russian spy in Manhattan Project World War II; Arch Moore, former Governor of West Virginia; Peter A. Peyser, US Congressman; Andrija Puharich, physician and parapsychologist; Jerry Rosholt, author and historian; Gore Vidal, author and politician; Kurt Vonnegut, author and Charles Warren, California politician.

The success of the division’s reconstitution effort was put to the test during the early hours of Dec 16, 1944. Massed to the east of the 28-ID, were elements of Gen Hasso Eccard Freiherr von Manteuffel’s 5.Panzer-Army, a total of 11 divisions, including 4 armored divisions: the 246.Volksgrenadier-Division (Gen Peter Körte); the 526.Infantry-Reserve-Division (Gen Kurt Schmidt); the 10.SS-Panzer-Division (Frundsberg) (Brigadeführer Heinz Harmel); (XII.SS-Armeekorps – Gen Günther Blumentritt); the 176.Infanterie-Division (Gen Christian-Johannes Landau); (XXXXVII.Panzerkorps – Gen Heinrich Lüttwitz and subordinated to Blumentritt’s XII.SS-Armeekorps); the 15.Panzer-Grenadier-Division (Oberst Hans-Joachim Deckert); the 183.Volksgrenadier-Division (Gen Wolfgang Lange); the 9.Panzer-Division (Gen Harald Freiherr von Elverfeldt); (LXXXI. Armeekorps – Gen Friedrich Köchling); the 340.Volksgrenadier-Division (Gen Theodor Tolsdorff); the 3.Panzer-Grenadier-Division (Gen Walter Denkert); the 12.Volksgrenadier-Division (Gen Gerhard Engel); the 47.Volksgrenadier-Division (Gen Max Bork). This being the Order of Battle on Nov 26, 1944.

The German assault, commonly known as the Ardennes Offensive or the Battle of the Bulge, caught the 28-ID and the entire allied army by surprise. German infantry units easily infiltrated the thinly held front of the 28-ID. The 110-IR in the center had a frontage of some fifteen miles. It was this regiment that received the heaviest blow from the German assault. The regiment, sitting astride one of the major routes to Bastogne, received orders to hold at all costs and they did just that. Fighting from a series of isolated company strong points, the 110-IR provided stiff resistance. From the very first day the division and regimental headquarters lost all ability to control the battle; forces were simply too scattered and the German attack too large.

The German assault, commonly known as the Ardennes Offensive or the Battle of the Bulge, caught the 28-ID and the entire allied army by surprise. German infantry units easily infiltrated the thinly held front of the 28-ID. The 110-IR in the center had a frontage of some fifteen miles. It was this regiment that received the heaviest blow from the German assault. The regiment, sitting astride one of the major routes to Bastogne, received orders to hold at all costs and they did just that. Fighting from a series of isolated company strong points, the 110-IR provided stiff resistance. From the very first day the division and regimental headquarters lost all ability to control the battle; forces were simply too scattered and the German attack too large.

The bypassed units, however, maintained tough defenses for almost two full days. This heroic defense helped provide the necessary time for the 101-A/B to occupy the key town of Bastogne and the 82-A/B the vicinity of Lierneux. This feat was particularly remarkable given the fact that more than 50 percent of every line company consisted of soldiers fighting their first battle. Some of the defenders were able to escape and make their way to the west, but the Germans managed to kill or capture the majority of the 110-IR soldiers.

For the second straight month the 28-ID had one of its regiments almost completely destroyed. To the north, the pressure on the 112-IR was not as great on Dec 16, as it was for its sister regiment, the 110-IR. The 112-IR also held a front some ten miles shorter than that of the 110-IR. Initially the regiment was able to hold its ground, but by Dec 17, the pressure from infiltrators in the unit rear was becoming too much to ignore. Gradually the regiment began to withdraw to the west of the Our River, maintaining good order as it executed this tough task. Despite the heavy fighting and the confusing situation, the regiment remained intact as a fighting force and struck the German attackers a stiff blow.

On Dec 18, the regiment found itself completely cut off from the remainder of the 28-ID. For the remainder of the battle the regiment would fight under the control of other divisions, including the 106-ID and the 82-A/B. It played a major part in the desperate fighting to hold the northern shoulder of the German penetration.

On Dec 18, the regiment found itself completely cut off from the remainder of the 28-ID. For the remainder of the battle the regiment would fight under the control of other divisions, including the 106-ID and the 82-A/B. It played a major part in the desperate fighting to hold the northern shoulder of the German penetration.

For its actions during the Battle of the Bulge, the 112-IR was later awarded the Presidential Unit Citation. This was a remarkable turn-around for a unit that had two of its battalions collapse and flee the battlefield during the Hürtgen Forest Campaign.

In the south, the 109-IR faced a situation similar to that of the 112-IR. From the very first day of the attack, the 109-IR was cut off from the remainder of the division. The fighting power of the regiment remained strong, however, and the 109-IR did not withdraw from its initial positions until the evening of

In the south, the 109-IR faced a situation similar to that of the 112-IR. From the very first day of the attack, the 109-IR was cut off from the remainder of the division. The fighting power of the regiment remained strong, however, and the 109-IR did not withdraw from its initial positions until the evening of  Dec 18. That night, the regiment withdrew further to the south across the Sure River, later blowing two important bridges. The 109-IR managed to withdraw in good order and remained an effective fighting force.

Dec 18. That night, the regiment withdrew further to the south across the Sure River, later blowing two important bridges. The 109-IR managed to withdraw in good order and remained an effective fighting force.

On Dec 19, the regiment passed to the control of the 10-AD. Along with the elements of the 4-ID as well as elements of the 9-AD, the 109-IR would help form the southern shoulder of the German penetration.

The actions of the 28-ID during the Battle of the Bulge were by all measures an enormous success, albeit one that came at a very high cost. The 110-IR provided the critical time necessary for the 101-A/B and other forces to secure the Belgian vital town of Bastogne.

The actions of the 28-ID during the Battle of the Bulge were by all measures an enormous success, albeit one that came at a very high cost. The 110-IR provided the critical time necessary for the 101-A/B and other forces to secure the Belgian vital town of Bastogne.

The 12th Army Group commander, Gen Omar N. Bradley, considered the actions of the 110-IR as one of the decisive elements of the battle. In his book, A Soldier’s Story, he wrote:

The 12th Army Group commander, Gen Omar N. Bradley, considered the actions of the 110-IR as one of the decisive elements of the battle. In his book, A Soldier’s Story, he wrote:

In valor, however, neither the 7-AD and the 4-ID had outshone the broken and bruised 28-ID. Though overrun by the first wave of Germans that moved out of the mists of the Schnee Eifel, the 28-ID split into a forest fill of small delaying units. For three sleepless days and nights the embattled troops of that division backed grudgingly towards Bastogne buying time for the reinforcement of that anchor position.

Both, the 109-IR and 112-IR performed equally well as they fought to hold the shoulders of the German penetration. The division’s reconstitution efforts following the Hürtgen Forest Campaign proved to be extremely effective. As the Battle of the Bulge came to a close, the 28-ID once more began to rebuild its broken units.

Casualties during the fighting in the Ardennes were very high. The 110-ID virtually ceased to exist as a regiment and suffered more than 2500 casualties.

The 109-IR and the 112-IR fared better, sustaining heavy casualties but remaining intact as regiments. During this reconstitution process the division drew on the valuable experiences gained in the wake of their Siegfried Line and Hürtgen Forest Campaigns. These lessons proved very beneficial in the aftermath of the Battle of the Bulge. Less than three weeks after the division ceased operations in the Ardennes, it received new orders to move south and begin preparations for offensive operations. By the end of January 1945, the division would be heavily involved in offensive operations to eliminate the Colmar Pocket in the Vosges Mountains of France.

The 109-IR and the 112-IR fared better, sustaining heavy casualties but remaining intact as regiments. During this reconstitution process the division drew on the valuable experiences gained in the wake of their Siegfried Line and Hürtgen Forest Campaigns. These lessons proved very beneficial in the aftermath of the Battle of the Bulge. Less than three weeks after the division ceased operations in the Ardennes, it received new orders to move south and begin preparations for offensive operations. By the end of January 1945, the division would be heavily involved in offensive operations to eliminate the Colmar Pocket in the Vosges Mountains of France.

Order of Battle – Nov 1944 – Jan 1945

Headquarters Company, 28th Infantry Division

Special Troops

109th Infantry Regiment

110th Infantry Regiment

112th Infantry Regiment

Headquarters Battery Division Artillery

107th Field Artillery Battalion (105-MM How)

108st Field Artillery Battalion (155-MM How)

109th Field Artillery Battalion (105-MM How)

229th Field Artillery Battalion (105-MM How)

103rd Engineer Combat Battalion

103rd Medical Battalion

28th Quartermaster Company

28th Reconnaissance Troop (Mecz)

28th Signal Company

728th Ordnance Light Maintenance Company

Military Police Platoon

Band, 28th Infantry Division

Units Attached to the 28th Infantry Division

2nd Bn, (Fr 2d Military Region), Jan 2 1945 – Jan 16 1945

2nd Ranger Bn, Nov 14 1944 – Nov 19 1944

3rd Bn, (Fr 2d Military Region)(106th Inf Co), Jan 2 1945 – Jan 16 1945

4th Bn, (Fr 2d Military Region), Jan 2 1945 – Jan 16 1945

4th Bn, (Fr 20th Military Region), Jan 2 1945 – Jan 16 1945

4-ECB, 1st Plat Baker Co, (4-ID), Nov 6 1944 – Nov 10 1944

7-TD Group (-), Dec 27 1944 – Dec 30 1944

5th Bn, (Fr 20th Military Region), Jan 2 1945 – Jan 16 1945

6th Bn, (Fr 2d Military Region), Jan 2 1945 – Jan 16 1945

8th Bn, (Fr 2d Military Region), Jan 2 1945 – Jan 16 1945

9-AD CCB, Jan 9 1945 – Jan 10 1945

9th Bn, (Fr 2d Military Region), Jan 2 1945 – Jan 16 1945

12-RCT (4-ID), Nov 6 1944 – Nov 10 1944

14th Bn, (Fr 20th Military Region), Jan 2 1945 – Jan 16 1945

20-ECB, (1171-ECG), Oct 24 1944 – Nov 19 1944

32-CRS, Nov 19 1944 – Dec 10 1944

42-FAB, (105-MM How)(4-ID), Nov 6 1944 – Nov 10 1944

44-ECB, Dec 17 1944 – Dec 25 1944

58-AFAB, Dec 17 1944 – Dec 23 1944

73-AFAB (9-AD), Dec 24 1944 – Dec 29 1944

76-FAB (105-MM How), Oct 28 1944 – Nov 19 1944

86-CMB (Mortar) less Charlie Co, Oct 28 1944 – Nov 19 1944

Charlie Co 86-CMD (Mortar), Oct 28 1944 – Nov 15 1944

Dog Co 87-CB, Oct 26 1944 – Nov 4 1944

146-ECB less Baker Co, Oct 30 1944 – Nov 19 1944

302-RCT (94-ID), Jan 8 1945 – Jan 10 1945

319-ECB, (1st Plat)(94-ID), Jan 8 1945 – Jan 10 1945

356-FAB (105-MM How)(94-ID), Jan 8 1945 – Jan 10 1945

602-TDB, (SP)(-), Dec 24 1944 – Dec 31 1944

630-TDB, (T), Jan 19 1945 – Mar 13 1945

687-FAB (105-MM How), Nov 19 1944 – Jan 1 1945

707-TB, Oct 6 1944 – Jan 8 1945

770-FAB (105-MM G), Dec 24 1944 – Dec 29 1944

801-TDB, (SP), A Co, Nov 6 1944 – Nov 10 1944

893-TDB, (SP), (- Co A), Oct 29 1944 – Nov 19 1944

987-FAB, (155-MM G) Btry A, Oct 7 1944 – Nov 9 1944

1340-ECB, (1171-ECB) Oct 24 1944 – Nov 19 1944

We received a certain amount of replacements; but I can think of making this easier, at least my mind tells me, it would be simplified and more practical to shoot them in the vicinity of their debarkation, as to make the attempt to return the bodies from where they fell and to bury some. It takes manpower to transport them back, and gasoline and manpower to bury them. These people could have fought as well and been killed too.

We received a certain amount of replacements; but I can think of making this easier, at least my mind tells me, it would be simplified and more practical to shoot them in the vicinity of their debarkation, as to make the attempt to return the bodies from where they fell and to bury some. It takes manpower to transport them back, and gasoline and manpower to bury them. These people could have fought as well and been killed too.

(Above) Ernest Hemingway, Personal notes while serving as a war correspondent with the US 4th Infantry Division, November 1944. Quoted by Ella Bieroth, from a yearbook issued the Eifelverein in Dueren, Germany, September 1969. Translated by Werner Kleeman. Obtained from the Ella Bieroth Papers at the US Army Military History Institute, Carlisle Barracks, PA.

During World War Two, Ernest Hemingway served as a war correspondent in the ETO and frequently operated with the 4-ID. When he set these words to paper, the 4-ID was in the midst of its own ordeal in the Hürtgen Forest. Following close on the heels of the 28-ID, the 4-ID fought for nearly a month and incurred almost 6000 casualties, more than 4900 replacements poured into the division during this month. Hemingway’s remarks could just have easily described the experiences of the 28-ID or those of the 1-ID which also suffered heavily in the Hürtgen Forest. Probably no other battle in the ETO so graphically demonstrated the profligate waste of lives that was characteristic of the American system for manning infantry units. To use the term system is rather inaccurate, there never existed a clear plan of how the army would keep its small force ofinfantry units filled with riflemen during combat. Instead, the army patched together a collection of systems and a collection of plans, all of which were inadequate to meet the demands of modem warfare.

The army underestimated not only what those demands would mean in terms of quantity of infantrymen, but in terms of quality as well. Realization of these planning errors came late in the war and the army had to resort to a wide variety of stop gap measures to keep its combat units operational That units eventually overcame the effects of such measures is a tribute to the soldiers and leaders of the squads, platoons, companies, and battalions that fought the ground war. That units had to endure such measures is a condemnation of the ‘system’ that needlessly sacrificed the lives of American soldiers. To attach blame for the failures of this system is a difficult task. No single person nor organization stands out clearly. It was a combination of decisions and actions at virtually every level that eventually produced the US Army personnel system. To best analyze these actions it is beneficial to consider the principal organizations in relation to the three levels of war: (1) strategic, (2) operational and (3) tactical. The War Department and ETOUSA (European Theater of Operations US Army) comprised the strategic level of the manning system. The operational level included army groups and field armies, as well as the actual operator of the theater replacement system, the Ground Forces Replacement Command. Corps, divisions, and regiments formed the tactical level.