(Malmedy Trial Investigation – statement of Edmund Zeger)

(Malmedy Trial Investigation – statement of Edmund Zeger)

Interrogated during the screening of suspects Nov 1945, he was a mechanic of the 501.Heavy-Tank-Battalion. He claimed there were 14 tanks from his company, but only 2 were actually with Kampfgruppe Peiper because the other 12 had motor trouble along the way. He repaired them and arrived at Engelsdrog (Ligneuville) on Dec 20.

The following report was presented to the Committee on Armed Services by the subcommittee chairman, Senator Raymond E. Baldwin, at the committee meeting on Oct 13. The report was unanimously approved by the committee and Senator Baldwin thereupon presented it to the Senate on Oct 14, 1949.

On Mar 29, 1949, a subcommittee of the Senate Armed Services Committee, consisting of Senators Raymond E. Baldwin (chairman), Estes Kefauver, and Lester O. Hunt was appointed to consider Senate Resolution 42. This resolution was introduced for the purpose of securing consideration of certain charges which had been made concerning the conduct of the prosecution in the Malmedy Atrocity Case and to effectuate a thorough study of the court  procedures and post-trial reviews of the case. It must be clearly understood that the function of this subcommittee is a legislative one only. It is not the function of this subcommittee, therefore, to retry the cases, to act as a board of appeals or reviewing authority, or to make any recommendations concerning the sentences.

procedures and post-trial reviews of the case. It must be clearly understood that the function of this subcommittee is a legislative one only. It is not the function of this subcommittee, therefore, to retry the cases, to act as a board of appeals or reviewing authority, or to make any recommendations concerning the sentences.

The subcommittee has, however, found it necessary to fully review the investigative and trial procedure in order to make its recommendations. The investigation automatically divided itself into specific phases; the first dealing with the charges of physical mistreatment and duress on the part of the War Crimes Investigation personnel; the second covering those matters of law and legal procedure which should be examined in an effort to determine their propriety and the degree to which they might be improved to meet future requirements.

As the investigation proceeded, a third phase evolved which has caused considerable concern and which deals with the motivation behind the current efforts to discredit the American military government in general and using the war crimes procedures in particular, as a part of that plan. During the conduct of the investigations, the subcommittee and its staff held hearings extending over a period of several months, examined 108 witnesses, and independently, as well as through other agencies, of the Government, conducted careful investigations into certain of the matters germane to the subject. It should be pointed out that witnesses representing every phase of this problem were heard, including persons who were imprisoned at  Schwabisch Hall, their attorneys, members of the investigating team, members of the court who tried the cases, the reviewing officers who reviewed the record of the trial, religious leaders, other interested parties.

Schwabisch Hall, their attorneys, members of the investigating team, members of the court who tried the cases, the reviewing officers who reviewed the record of the trial, religious leaders, other interested parties.

Every witness who was suggested to the subcommittee, or whom it discovered through its own efforts, was heard and carefully examined by the members of the subcommittee, other interested Senators, and the subcommittee staff. All affidavits submitted to the committee have been translated and studied. It is felt that the record is complete and adequate to support the findings and conclusions in this respect. An important part of the investigation was the conducting of a complete physical examination of many of those persons who claimed physical mistreatment, some of whom alleged they received permanent injuries of a nature capable of accurate determination. These examinations were conducted by a staff of outstanding doctors and dentists from the Public Health Service of the United States. Advice and assistance were also requested from the American Bar Association and other groups with particular knowledge in the field of law and military courts and commissions.

What were the Malmedy Atrocities?

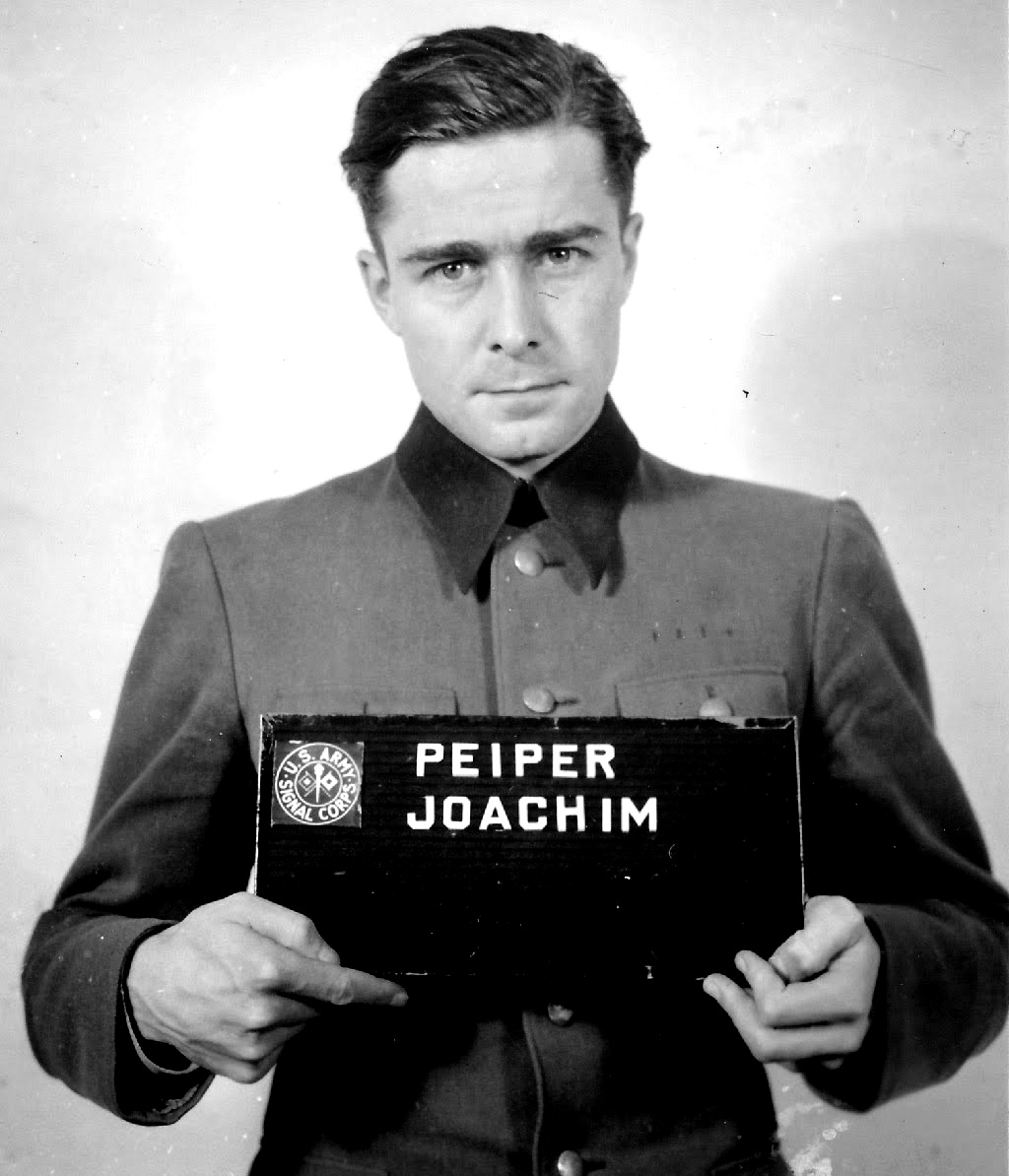

In the minds of a great many persons, the Malmedy atrocities are limited to those connected with the Malmedy crossroads (Five Point Crossroads – Baugnez) incident which, in fact, is only a part of the charges preferred against the German SS troopers in this particular case. The atrocities with which the accused in the Malmedy case were charged were part of a series committed at several localities in Belgium, starting on Dec 17, 1944, and lasting until approximately Jan 13, 1945. They occurred during the so-called Battle of the Bulge and were committed by the organization known as Kampfgruppe Peiper, essentially the 1.SS-Panzer-Regiment commanded by SS-Obersturmbahnfuehrer Joachim Peiper. All the members of this combat team, and particularly those involved in the Malmedy trial were members of the Waffen SS organization. The regiment had had a long and notorious military record on both the western and eastern fronts.On the eastern front, one of the battalions of the Kampfgruppe Peiper, while commanded by Peiper, earned the nickname of Blow Torch Battalion after burning two villages and killing all the inhabitants thereof. Peiper had at one time been an adjutant to SS-Reichfuehrer Heinrich Himmler. The prisoners under investigation were for the most part hardened veterans. Basically, the atrocities which were committed at 12 places throughout Belgium consisted, according to accounts of different witnesses, of the killing of approximately 350 unarmed American prisoners of war, after they had surrendered, and 100 Belgian civilians.

They occurred during the so-called Battle of the Bulge and were committed by the organization known as Kampfgruppe Peiper, essentially the 1.SS-Panzer-Regiment commanded by SS-Obersturmbahnfuehrer Joachim Peiper. All the members of this combat team, and particularly those involved in the Malmedy trial were members of the Waffen SS organization. The regiment had had a long and notorious military record on both the western and eastern fronts.On the eastern front, one of the battalions of the Kampfgruppe Peiper, while commanded by Peiper, earned the nickname of Blow Torch Battalion after burning two villages and killing all the inhabitants thereof. Peiper had at one time been an adjutant to SS-Reichfuehrer Heinrich Himmler. The prisoners under investigation were for the most part hardened veterans. Basically, the atrocities which were committed at 12 places throughout Belgium consisted, according to accounts of different witnesses, of the killing of approximately 350 unarmed American prisoners of war, after they had surrendered, and 100 Belgian civilians.

Location – Date – PWs – Civilians

Honsfeld, Dec 17, 1944, 19 – 0

Bullingen, Dec 17, 1944, 50 – 1

Crossroads, Dec 17, 1944, 86 – 0

Ligneuville, Dec 17, 1944, 58 – 0

Stavelot, Dec 18-21, 1944, 8 – 93

Cheneux, Dec 17-18, 1944, 31 – 0

La Gleize, Dec 18, 1944, 45 – 0

Stoumont, Dec 19, 1944, 44 – 1

Wanne Dec 20-21, 1944, 0 – 5

Wanne Dec 20-21, 1944, 0 – 5

Lutrebois, Dec 31, 1944, 0 – 1

Trois-Ponts, Dec 18-20, 1944, 11 – 10

Petit-Thier, Jan 10-13, 1945, 1 – 0

Development of Pre-Trial Investigation

Concurrently with the defeat of the Germans in the Battle of the Bulge, investigations were started concerning the massacre of American PWs. This preliminary work resulted in a determination that the Malmedy massacre had in all probability been perpetrated by personnel of the Kampfgruppe Peiper, who were scattered throughout prison camps, hospitals, and labor detachments in Germany, Austria, the liberated countries, and even the USA. Conditions in the prison camps, however, were such that after interrogation, those interrogated were able to rejoin their comrades and all soon knew exactly what information the investigators desired. It became clear that the suspects could not be properly interrogated until facilities were available which would prevent them from communicating with each other before and during and after interrogation. According to the evidence submitted to the subcommittee, it was during this period that it became known that prior to the beginning of the Ardenne offensive, the SS troops were sworn to secrecy regarding any orders they had received concerning the killing of PWs.

In accordance with the plan for further investigation of this case, all the members of the Kampfgruppe Peiper were transferred to the internment camp at Zuffenhausen. They were initially there housed in a single barracks where it was still impossible to maintain any security of communication between the accused. During this time it was learned that SS Oberstrumbahnfuehrer Peiper gave instructions to blame the Malmedy massacre on Sturmbahnfuehrer Werner Poetchke, who had been killed in Austria during the last days of the war.

In accordance with the plan for further investigation of this case, all the members of the Kampfgruppe Peiper were transferred to the internment camp at Zuffenhausen. They were initially there housed in a single barracks where it was still impossible to maintain any security of communication between the accused. During this time it was learned that SS Oberstrumbahnfuehrer Peiper gave instructions to blame the Malmedy massacre on Sturmbahnfuehrer Werner Poetchke, who had been killed in Austria during the last days of the war.

These orders were carefully followed by those under investigation. Accordingly, further steps were deemed to be necessary, and those prisoners who were still suspect were evacuated to an interrogation center at Schwabisch Hall, where they were housed in an up-to-date German prison, but were during the investigation they were kept in cells by themselves. Initially, there were over 400 of these prisoners evacuated to Schwabisch Hall, and from time to time others were transferred to the prison, up to and including the latter part of March 1946. It was during this period of interrogation at Schwabisch Hall that the alleged mistreatment of prisoners took place.

Findings and Conclusions

For the purposes of this report, the matters under discussion are separated according to the three phases of the investigation set out above, i. e.: matters of duress during the pretrial investigation; trial and review procedures; the manner in which the current situation has been agitated.

(1) Matters of duress during the pre-trial investigation

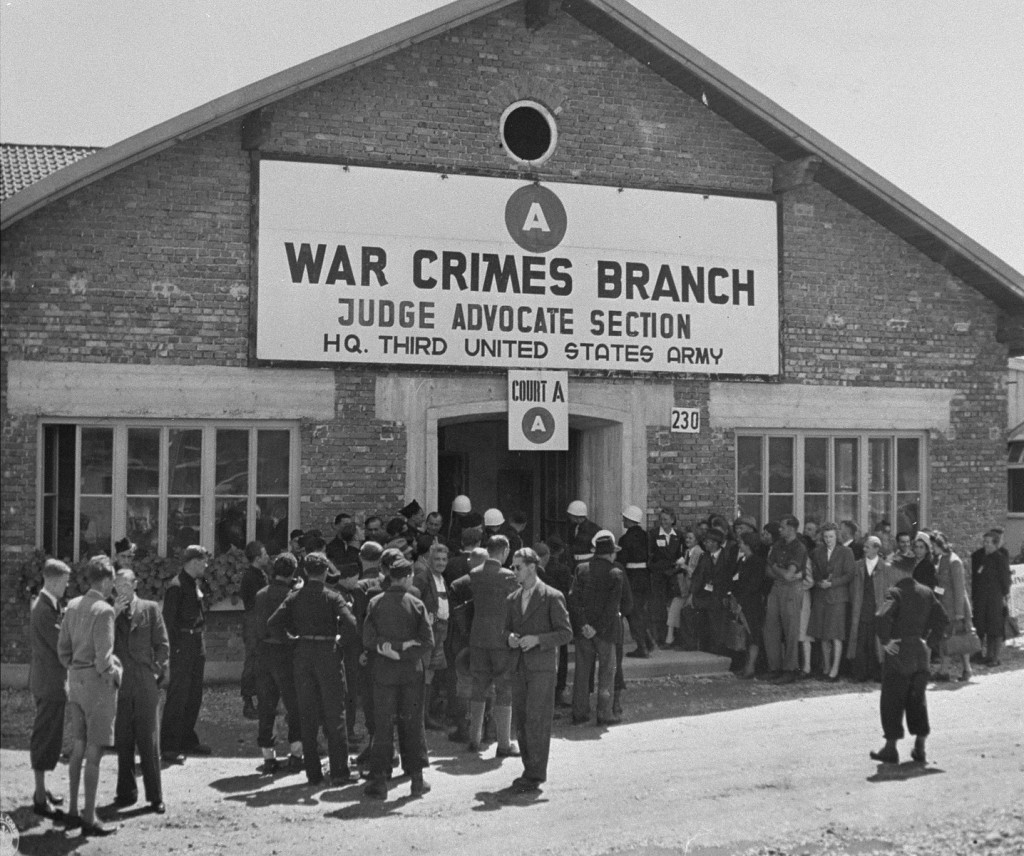

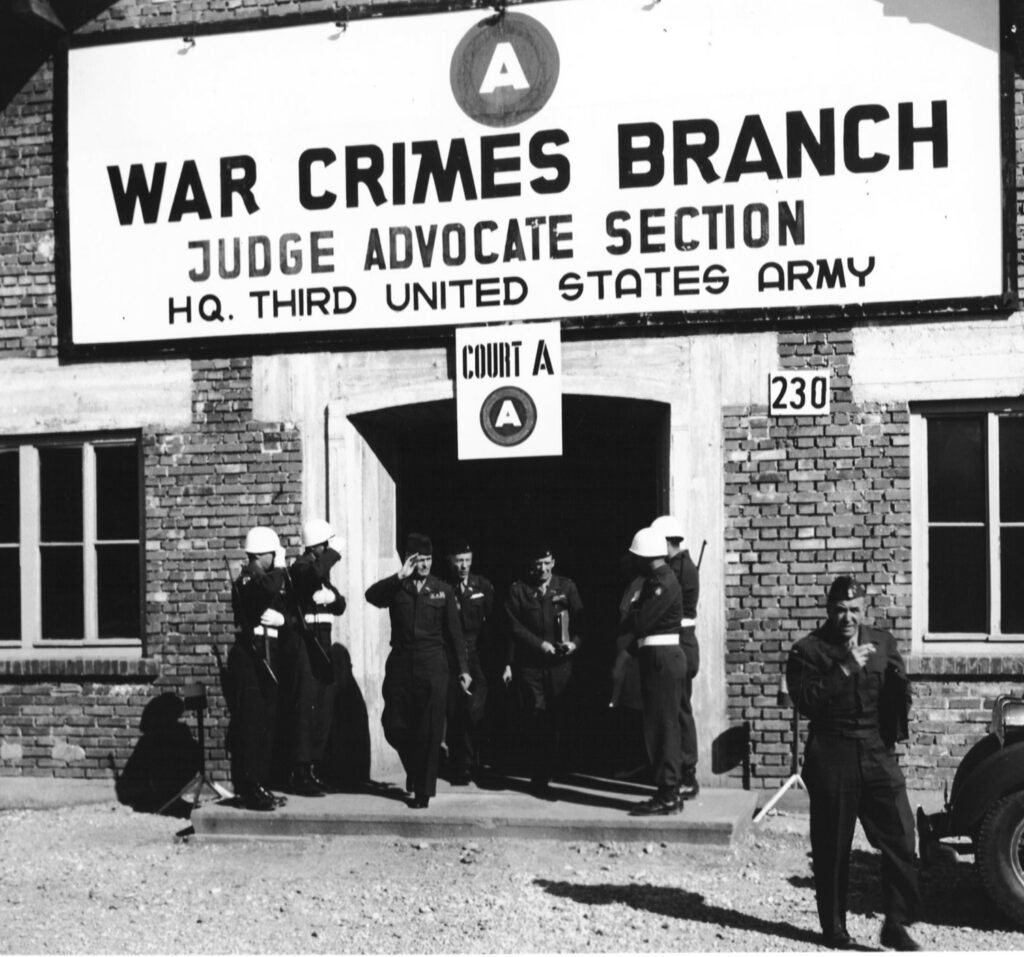

During 1948 and 1949 charges were made which caused considerable publicity concerning the treatment of these SS prisoners at Schwabisch Hall. The prisoners were confined at Schwabisch Hall from Dec 1945 to Apr 1946 and the pretrial investigations occurred then. In Apr 1946 the pretrial investigations having been completed the prisoners were removed to Dachau. There their trial began on May 16 and continued until Jul 16. Shortly after the defense counsel began to work on the case at Dachau, they prepared a questionnaire for distribution to the accused, which contained, among other things, questions concerning any physical abuse duress.

The subcommittee made every effort to secure the original of these executed questionnaires but they were apparently destroyed when the case was over.

The subcommittee made every effort to secure the original of these executed questionnaires but they were apparently destroyed when the case was over.

As a result of information furnished on these questionnaires and statements that had been made concerning duress, the defense counsel before trial, through their chief counsel, Col Willis M. Everett reported the matter to the US 3-A judge advocate in charge of war crimes. Col Everett later conferred with the deputy theater judge advocate general for war crimes who ordered an investigation to be conducted at once by Col Edwin J. Carpenter, who testified before the subcommittee.During his investigation which was completed before the trial, between 20 and 30 of the accused who made the most serious charges of duress were examined. According to Col Carpenter’s testimony before the subcommittee, which was confirmed by independent testimony given by the interpreter used by him at that time, only four of this group stated that anyone had abused them physically. These four did not claim physical abuse in connection with securing confessions, but rather punchings and pushing by guards while being moved from one cell to another. However, during his investigation, considerable emphasis was placed on the use of so-called mock trials, solitary confinement, and mention was made of the use of hoods, and insults.

The investigating officer, in this case, Col Carpenter, and the deputy theater judge advocate for war crimes Col Claude B. Mickelwaite, to whom these charges were made stated to the subcommittee that they felt the seriousness of the matters reported by the defense counsel was not established and therefore were not of particular import, but that the use of some of the tricks, and in particular the mock trials had been established, and  should be explained to the court at the start of the trial so that it could weigh evidence introduced in the light of the accusations made by the accused. At the time of the trial, 9 of the 74 accused took the stand on their own behalf. Of this number, 3 alleged physical mistreatment. The court was thereby placed on notice of the charges of physical mistreatment made by those who took the stand on their own behalf and apparently did not feel that it was of such importance as to require any further investigation or study. Some 16 months after conviction, practically every one of the accused began to submit affidavits repudiating their former confessions and alleging aggravated duress of all types.

should be explained to the court at the start of the trial so that it could weigh evidence introduced in the light of the accusations made by the accused. At the time of the trial, 9 of the 74 accused took the stand on their own behalf. Of this number, 3 alleged physical mistreatment. The court was thereby placed on notice of the charges of physical mistreatment made by those who took the stand on their own behalf and apparently did not feel that it was of such importance as to require any further investigation or study. Some 16 months after conviction, practically every one of the accused began to submit affidavits repudiating their former confessions and alleging aggravated duress of all types.

The word ‘confession’ has been used to describe the documents secured from the prisoners. These were in fact, in large part, statements which described places, dates, and events in which the signer took part or witnessed the acts and conduct of other accused. These affidavits were secured by German attorneys, particularly Dr. Eugen Leer, a defense counsel at the trial, who is the most active attorney in this case at the present time. These affidavits were later used by Col W. M. Everett in his petition to the Supreme Court for a writ of habeas corpus in this case. In addition, affidavits to such matters were, in a few cases, submitted by others who were at Schwabisch Hall but who were not defendants in the many of these affidavits were so lurid in their claims as to shock even the most calloused reader. The subcommittee accordingly has gone to great lengths to attempt to establish the facts as they pertain to these matters. Before proceeding with an item-by-item discussion of the types of duress alleged by various persons, it is  necessary to describe in some detail the prison at Schwabisch Hall and its method of operation.

necessary to describe in some detail the prison at Schwabisch Hall and its method of operation.

The prison is located in the heart of a thriving and prosperous city of approximately 25.000 population and is a modern stone-and-concrete prison for civil prisoners. Since it is located at the foot of a hill, it is possible for persons living next to the prison, on the higher ground, to look down into the prison yard, and on quiet nights to hear sounds from within the prison enclosure. This prison was taken over by the US authorities primarily for use as an internment center for political prisoners. However, when it was decided to concentrate the Malmedy suspects at this point, a portion of the prison was set aside for the housing and interrogation of these men. They were separated completely from the political prisoners, with the exception of a few of the internees who performed routine prison duties. These few gained some knowledge of the handling of the Malmedy suspects but were forbidden to speak to them.

The administration of Schwabisch Hall prison was under the control of the Seventh Army and there was a detachment stationed at the prison for this purpose. This group was headed by Capt John T. Evans, who testified before the subcommittee and who described in detail the normal prison administration. His organization was responsible for the housing, guarding, feeding, clothing, medical care, well-being, and all other matters pertaining to the prisoners.

The administration of Schwabisch Hall prison was under the control of the Seventh Army and there was a detachment stationed at the prison for this purpose. This group was headed by Capt John T. Evans, who testified before the subcommittee and who described in detail the normal prison administration. His organization was responsible for the housing, guarding, feeding, clothing, medical care, well-being, and all other matters pertaining to the prisoners.

The men who conducted the interrogation were members of a war crime investigating team sent down to the prison from the War Crimes Branch through Third Army Headquarters. They had no responsibility other than to prepare the case for trial and no control over the administrative functions of the prison. There was a considerable difference in the method in which the Malmedy suspects and the political prisoners were handled.  The medical care of the Malmedy prisoners was charged to an American medical detachment stationed at the prison, with necessary hospitalization being handled in nearby US Army hospitals. According to the testimony given, the subcommittee, all such medical matters were handled by American medical personnel, and only a few of the dental cases were treated by a German civilian dentist who came into the prison periodically for the purpose of treating the internees. As to the manner of providing dental care, there is considerable variance in the testimony introduced before the subcommittee, and it will be discussed in detail later in this report. The internees were cared for by German medical personnel who were interned in the prison or who were brought in from the outside.

The medical care of the Malmedy prisoners was charged to an American medical detachment stationed at the prison, with necessary hospitalization being handled in nearby US Army hospitals. According to the testimony given, the subcommittee, all such medical matters were handled by American medical personnel, and only a few of the dental cases were treated by a German civilian dentist who came into the prison periodically for the purpose of treating the internees. As to the manner of providing dental care, there is considerable variance in the testimony introduced before the subcommittee, and it will be discussed in detail later in this report. The internees were cared for by German medical personnel who were interned in the prison or who were brought in from the outside.

The interrogation team, consisting of approximately 12 members, set up offices in one wing of the prison. They were primarily on the second floor, and in this same wing, there were cells used for interrogation as well as for administrative activities. In addition, there were five cells which in design and construction were different from the normal cells found throughout the prison. The subcommittee checked many of the prison cells. The normal ones, without exception, were well-lighted, adequate in size for two or more occupants, had toilets, and were on a central heating plant with radiators that apparently were working during the time the prison was occupied by the Malmedy suspects. These cells were of solid construction with a solid door containing a small peephole through which the occupant could be seen and heard. Loud conversation or noise within the cells could be heard by occupants of other cells, and, of course, if they called through the windows it could be heard pretty generally throughout the prison.

The five cells referred to, which were located immediately adjacent to the cells used for interrogation, differed in that they had smaller windows that were higher in the room and therefore did not give as much light. The cells were adequate, as far as size was concerned, for one or two occupants. They all had flush toilets. However, there was an interior iron grille immediately inside the main door which separated the prisoner from the door itself.

The five cells referred to, which were located immediately adjacent to the cells used for interrogation, differed in that they had smaller windows that were higher in the room and therefore did not give as much light. The cells were adequate, as far as size was concerned, for one or two occupants. They all had flush toilets. However, there was an interior iron grille immediately inside the main door which separated the prisoner from the door itself.

Food could be, and according to testimony before the subcommittee was, passed to the prisoners through an aperture in the steel grille at the lower part of the grille on the right-hand side as the cells were entered. It was in these five cells that prisoners were retained during certain phases of their interrogation. They have been labeled by various persons as dead cells, dark cells, and solitary confinement cells. From the standpoint of physical confinement, there is no evidence before the subcommittee to indicate that these cells were any worse than are to be found in any normal prison. However, there is much conflicting testimony as to their use. Members of the interrogation team, testifying before the subcommittee, stated that no one was confined in these cells for longer than 2 or 3 days at a time, during which they received normal treatment and rations. Other statements have been made to the effect that prisoners were kept in the special cells for weeks on and, some alleged, without food. Others said they were fed but stayed there for long periods. In that connection, it should be pointed out that there are only five such cells and several hundred suspects were screened during a period of 4 months.

The bulk of the Malmedy suspects were housed in a cell block in a wing of the prison which was separated from the interrogation cells by a courtyard. Immediately adjacent to this wing, in which most of the Malmedy prisoners were housed, was a separate building which contained, on the second floor, a hospital dispensary used mainly for the political internees. The ground floor contained the prison kitchen. Up until the time individuals under interrogation for the Malmedy crimes had completed their interrogation, they were moved through this courtyard and between other points, with a black hood over their heads in order to insure security insofar as their knowing who else was under interrogation.