Document Source: The Story of the 106th Infantry Division, United States Army. Division Publication, Paris, France, 1945.

When the history of the Ardennes fighting has been written, it will be recorded as one of the great strategic Allied successes of the war in Europe. Tactically, for the 106-ID and the other American divisions involved, it was a bitter and a costly fight. But it becomes increasingly clear that the Germans expended in that last futile effort those last reserves of men and materiel which they needed so badly a few months later. The losses and sacrifices of the 16-ID paid great dividends in eventual victory. The text bellow is dedicated to those gallant men who refused to quit in the darkest hour of the Allied invasion, and whose fortitude and heroism turned the tide toward overwhelming victory.

When the history of the Ardennes fighting has been written, it will be recorded as one of the great strategic Allied successes of the war in Europe. Tactically, for the 106-ID and the other American divisions involved, it was a bitter and a costly fight. But it becomes increasingly clear that the Germans expended in that last futile effort those last reserves of men and materiel which they needed so badly a few months later. The losses and sacrifices of the 16-ID paid great dividends in eventual victory. The text bellow is dedicated to those gallant men who refused to quit in the darkest hour of the Allied invasion, and whose fortitude and heroism turned the tide toward overwhelming victory.

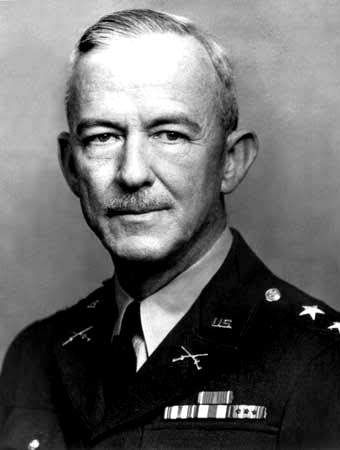

Gen Donald A. Stroh

February 1945

The Story of the 106th Infantry Division

December 16, 1944: springing from the bleak vastness of the Schnee Eifel with the speed of a coiled snake, Adolf Hitler’s desperate but mighty counter-offensive known today as the Offensive von Rundstedt, struck toward Belgium and the Ardennes. Carefully hoarded Panther and Tiger tanks, followed by crack, battle-tested infantry, launched the last-chance gamble aimed at shattering the taut lines of the US First Army, seizing the cities of Liège and Anvers and slashing through the Allied forces to the sea.

December 16, 1944: springing from the bleak vastness of the Schnee Eifel with the speed of a coiled snake, Adolf Hitler’s desperate but mighty counter-offensive known today as the Offensive von Rundstedt, struck toward Belgium and the Ardennes. Carefully hoarded Panther and Tiger tanks, followed by crack, battle-tested infantry, launched the last-chance gamble aimed at shattering the taut lines of the US First Army, seizing the cities of Liège and Anvers and slashing through the Allied forces to the sea.

The full force of this massive attack was thrown against the new, untried 106-ID which had gone into the front lines for the first time only five days previous. Two regiments, the 422-IR and

the 423-IR, with the 589-FAB and the 590th FAB, were cut off and surrounded by the sheer weight and power of the concentrated German hammer blows. The 424-IR, was driven back. The 106th Recon Troop, 331st Medical Bn, and 81st Engineer Combat Bn, suffered heavy casualties.

But, despite the vulnerable 27-mile front which the division had to defend, despite inadequate reserves, supplies and lack of air support, the valiant men of the Lion Division took a tremendous toll of enemy shock troops, wrote a story in blood and courage to rank with the Alamo, Chateau-Thierry, Pearl Harbor and Bataan. They never quit. Said FM Sir Bernard L. Montgomery: The American soldiers of the… 106th Infantry Division stuck it out and put up a fine performance. They stuck it out, those chaps.

At St Vith, first objective of the German thrust, the 106-ID held on grimly at a time when every hour of resistance was vita! to the Allied cause. The 106-ID doughs fought against superior forces, with pulverizing artillery battering them from all sides; it was men against tanks, guts against steel. Their heroism gained precious time for other units to regroup and strike back. In one of the bloodiest battles of the war, the 106-ID showed the Germans and the world how American soldiers could fight-and die.

When the terrific German onslaught was launched the 106-ID had only been on the Continent 10 days. The men had made a three-day road march from Limésy, France, to St Vith, Belgium, in rain, cold and snow. In the five days they had been in the line there had been little rest. They landed at Le Havre from England, December 6. Next day, in the dim half-light of dawn, troops piled into open trucks while a cold, drizzling rain fell. Some of the men laughed and made cracks about Sunny France.

Others cursed the rain, the cold, the fate that had sent them to battle-scarred Europe. Still others said nothing. In the clump of trees off to one side of the road stood what once had been a pretentious country chateau. It was decayed and rotten now. Bomb-cratered ground and the shell of a fire-gutted house gave evidence of what had passed. In a field across the road lay broken remains of an Allied bomber. It looked alone and dead; there was the feeling that someone ought to bury it. The scene was one of dreary foreboding.

Trucks roared over pitted, rough roads toward St Vith, through towns and battered remnants of villages; past burned skeletons of tanks and trucks in roadside ditches, around battlefields of World War One. People came out to smile, wave and make the V sign with their fingers. The men smiled back and made the V sign, too. As the long convoy wound through the mountains of eastern Belgium and Luxembourg, men saw the snow-covered evergreens and thought of Christmas, only a short time off. Then they stopped thinking about that because they remembered where they were and why they had come.

Arriving at St Vith the night of December 10, the division went into the line the next day.

It relieved the veteran 2nd Infantry Division in the Schnee Eifel, a wooded, snow covered ridge just northeast of Luxembourg. This was a quiet sector along the Belgium-Germany frontier. For 10 weeks there had been only light patrol activity and the sector was assigned to the 106-ID so it could gain experience. The baptism of fire that was to come was the first action for the division. For many of its men it was the last.

It relieved the veteran 2nd Infantry Division in the Schnee Eifel, a wooded, snow covered ridge just northeast of Luxembourg. This was a quiet sector along the Belgium-Germany frontier. For 10 weeks there had been only light patrol activity and the sector was assigned to the 106-ID so it could gain experience. The baptism of fire that was to come was the first action for the division. For many of its men it was the last.

Panzers Strike

106-ID Sticks it Out

Assigned to the VIII Corps, the 106-ID took up positions in a slightly bulging arc along a forest-crowned ridge of the Schnee Eife1 approximately 12 miles east of St Vith. The northern flank was held by the 14th Cavalry Group, attached to the 106-ID.

Assigned to the VIII Corps, the 106-ID took up positions in a slightly bulging arc along a forest-crowned ridge of the Schnee Eife1 approximately 12 miles east of St Vith. The northern flank was held by the 14th Cavalry Group, attached to the 106-ID.

Next, in the easternmost part of the curve, the 422-IR held the line. To the 422’s right, swinging slightly to the southwest, was the 423-IR and almost directly south was the 424-IR. Beyond the 424th, on the division’s southern flank was the 28-ID. The Headquarters of the 106-ID was located in St Vith while the rear echelon was in Vielsalm, about 12 miles due west. The little town and roads center of St Vith had seen war before.

Next, in the easternmost part of the curve, the 422-IR held the line. To the 422’s right, swinging slightly to the southwest, was the 423-IR and almost directly south was the 424-IR. Beyond the 424th, on the division’s southern flank was the 28-ID. The Headquarters of the 106-ID was located in St Vith while the rear echelon was in Vielsalm, about 12 miles due west. The little town and roads center of St Vith had seen war before.

It was through St Vith that the Nazi panzers rolled to Sedan in 1940; German infantry marched through it in 1914. But it never had figured as a battleground such as it was to become in this fateful December of 1944. During the night of December 15, front line units of the 106-ID noticed increased activity in the German positions. At 0530, the enemy began to lay down a thunderous artillery barrage.

It was through St Vith that the Nazi panzers rolled to Sedan in 1940; German infantry marched through it in 1914. But it never had figured as a battleground such as it was to become in this fateful December of 1944. During the night of December 15, front line units of the 106-ID noticed increased activity in the German positions. At 0530, the enemy began to lay down a thunderous artillery barrage.

At first, fire was directed mainly against the northern flank sector of the 14-CG. Slowly the barrage crept southward, smashing strong points along the whole division front. Treetops snapped like toothpicks under murderous shell bursts. Doughs burrowed into their foxholes and fortifications, waited tensely for the attack which would follow. The darkness was filled with bursts from medium and heavy field pieces plus railway artillery which had been shoved secretly into position. The explosions were deafening and grew into a terrifying hell of noise when the Nazis started using their Nebelwerfer (Screaming Meemies).

Full weight of the barrage was brought to bear on the 589-FAB, supporting the 422-IR. Hundreds of rounds blasted their positions in 35 minutes. At 0709 the barrage lifted in the forward areas, although St Vith remained under fire. Now came the attack. Waves of Volksgrenadiers, spearheaded by panzer units, smashed against the division’s lines in a desperate try for a decisive, early breakthrough. They were stopped. A second attack was thrown against the division. Again, the doughs held. Nazis threw in wave after wave of fresh troops, replacing their losses. There were no replacements for the 106. Lion men settled to their grim business, dug deeper, fought with everything they had. German bodies piled up, often at the very rim of the defenders’ foxholes.

Still the Nazis came.

All during the day, the attacks mounted in fury. Hundreds of fanatical Germans rushed straight toward the American lines, only to be mowed down or driven back by a hail of steel. Others came on, met the same fate. The deadly, careful fire of the stubborn defenders exacted a dreadful toll on the Wehrmacht. Finally, under pressure of overwhelming numbers, the 14-CG was forced to withdraw on the north flank, giving the Germans their first wedge in the division front.

All during the day, the attacks mounted in fury. Hundreds of fanatical Germans rushed straight toward the American lines, only to be mowed down or driven back by a hail of steel. Others came on, met the same fate. The deadly, careful fire of the stubborn defenders exacted a dreadful toll on the Wehrmacht. Finally, under pressure of overwhelming numbers, the 14-CG was forced to withdraw on the north flank, giving the Germans their first wedge in the division front.

Enemy tanks and infantry in increasing numbers then hacked at the slowly widening gap in an effort to surround the 422-IR. In the meantime, a second tank-led assault, supported by infantry and other panzers, hammered relentlessly at the 423-IR and the 424-IR. Early next morning a wedge was driven between the two regiments. This southern German column then swung north to join the one that had broken through in the 14-CG’s sector. The 422-IR and the 423-IR were surrounded. The 424-IR pulled back to St Vith.

The Nazis were headed for St Vith. There, cooks and clerks, truck drivers and mechanics shouldered weapons and took to the foxholes. Hopelessly outnumbered and facing heavier firepower, they dug in for a last ditch defense of the key road center. They were joined on December 17, by Combat Command B of the 9th Armored Division, and by the first element of Combat Command B of the 7th Armored Division. Surrounded, the 422-IR and the 423-IR fought on. Ammunition and food ran low. Appeals were radioed to HQ to have supplies flown in, but the soupy fog which covered the frozen countryside made air transport impossible. The two encircled regiments regrouped early on December 18, for a counter-attack aimed at breaking out of the steel trap. This bold thrust was blocked by sheer weight of German numbers. The valiant stand of the two fighting regiments inside the German lines was proving to be a serious obstacle to Nazi plans. It forced von Rundstedt to throw additional reserves into the drive to eliminate the surrounded Americans, enabled the remaining units and their reinforcements to prepare the heroic defense of St Vith, delayed the attack schedule and prevented the early stages of the Battle of the Bulge, from exploding into a complete German victory.

The Nazis were headed for St Vith. There, cooks and clerks, truck drivers and mechanics shouldered weapons and took to the foxholes. Hopelessly outnumbered and facing heavier firepower, they dug in for a last ditch defense of the key road center. They were joined on December 17, by Combat Command B of the 9th Armored Division, and by the first element of Combat Command B of the 7th Armored Division. Surrounded, the 422-IR and the 423-IR fought on. Ammunition and food ran low. Appeals were radioed to HQ to have supplies flown in, but the soupy fog which covered the frozen countryside made air transport impossible. The two encircled regiments regrouped early on December 18, for a counter-attack aimed at breaking out of the steel trap. This bold thrust was blocked by sheer weight of German numbers. The valiant stand of the two fighting regiments inside the German lines was proving to be a serious obstacle to Nazi plans. It forced von Rundstedt to throw additional reserves into the drive to eliminate the surrounded Americans, enabled the remaining units and their reinforcements to prepare the heroic defense of St Vith, delayed the attack schedule and prevented the early stages of the Battle of the Bulge, from exploding into a complete German victory.

Low on ammunition, food gone, ranks depleted by three days and nights of ceaseless fighting, the 422-IR and the 423-IR battled on from their foxholes and old Siegfried Line bunkers. They fought the ever growing horde of panzers with bazookas, rifles and machine guns. One of their last radio messages was, Can you get some ammunition through?

(Above : Technical Video US Army WW-2 – Powered by WordPress and EUCMH)

Then, no more was heard from the two encircled regiments except what news was brought back by small groups and individuals who escaped the trap. Many were known to have been killed. Many were missing. Many turned up later in German prison camps. Gen Courtney H. Hodges, 1-A commander, said of the 106-ID’s stand:

Then, no more was heard from the two encircled regiments except what news was brought back by small groups and individuals who escaped the trap. Many were known to have been killed. Many were missing. Many turned up later in German prison camps. Gen Courtney H. Hodges, 1-A commander, said of the 106-ID’s stand:

No troops in the world, disposed as your division had to be, could have withstood the impact of the German attack which had its greatest weight in your sector. Please tell these men for me what a grand job they did. By the delay they effected, the definitely upset von Rundstedt’s timetable.

Germans kept probing toward St Vith all during the night of December 17-18. Then, as daylight came, they renewed their furious and relentless attack. North of the town, elements of the 7-AD were in position.

Germans kept probing toward St Vith all during the night of December 17-18. Then, as daylight came, they renewed their furious and relentless attack. North of the town, elements of the 7-AD were in position.

To the south were the 424-IR and CCB 9-AD.

To the south were the 424-IR and CCB 9-AD.  Division Headquarters Defense Platoon, the 81st Engineer Combat Battalion, and the attached 168th Engineer Combat Battalion. A mighty see-saw battle churned over the entire area during the next three days. Raging at the unexpected snag in their plans and aware that precious hours were being lost with every delay, the Nazis unleashed repeated fanatic attacks along the whole, thin perimeter of the defenders. Time and time again they were thrown back.

Division Headquarters Defense Platoon, the 81st Engineer Combat Battalion, and the attached 168th Engineer Combat Battalion. A mighty see-saw battle churned over the entire area during the next three days. Raging at the unexpected snag in their plans and aware that precious hours were being lost with every delay, the Nazis unleashed repeated fanatic attacks along the whole, thin perimeter of the defenders. Time and time again they were thrown back.

Wounded Lions Claw Nazi Juggernaut

Feats of individual gallantry and courage against long odds were legion. Men alone and in little groups fought their way out of the surrounded units. For days, soldiers made their way back through enemy lines. Some fought with whatever outfits they found. During the early-hours of the Nazi assault, the 423-IR I&R Platoon, under 1/Lt Ivan H. Long (Pontiac, Mich), effectively held a road block. The Germans, learning at great cost that they could not smash through the block, went around. The platoon was faced with the alternative of surrendering or making a dash through enemy territory. The men were without overcoats or blankets. Among the 21 doughs were only four D-ration chocolate bars. They had little ammunition. But they fought their way through the snow and gnawing cold to rejoin the division with every man safe.

Feats of individual gallantry and courage against long odds were legion. Men alone and in little groups fought their way out of the surrounded units. For days, soldiers made their way back through enemy lines. Some fought with whatever outfits they found. During the early-hours of the Nazi assault, the 423-IR I&R Platoon, under 1/Lt Ivan H. Long (Pontiac, Mich), effectively held a road block. The Germans, learning at great cost that they could not smash through the block, went around. The platoon was faced with the alternative of surrendering or making a dash through enemy territory. The men were without overcoats or blankets. Among the 21 doughs were only four D-ration chocolate bars. They had little ammunition. But they fought their way through the snow and gnawing cold to rejoin the division with every man safe.

Cpl Willard Roper (Havre, Mont), led the group back as first scout. After 72 hours of clawing through enemy patrols, tank and machine gun positions, the exhausted and footsore men, some of whom had lost their helmets, could still grin and fight. One of the most noteworthy efforts at St Vith was the leadership of Col Thomas J. Riggs Jr (Huntington, WVa) commanding the 81-ECB. Once a midshipman at the US Naval Academy, Col Riggs first won fame as an All-America fullback at the University of Illinois. On the morning of December 17, Col Riggs took over the defense of the town. He disposed his limited forces, consisting of part of his own battalion; the Defense Platoon, 106th Hq Co, and elements of the 168-ECB, and waited for the coming blow. The wait was short. Soon a battalion of German infantry attacked behind armored vehicles and tanks. Time after time more tanks and infantry tackled the engineer line, probing for a weak spot. During these attacks, Col Riggs was in the center of the defense, rallying his men and personally heading counter-thrusts to keep the enemy off balance. Col Riggs was captured while leading a patrol in the defense of St Vith. Marched across Germany, he escaped near the Polish border and made his way to the frontier.

Cpl Willard Roper (Havre, Mont), led the group back as first scout. After 72 hours of clawing through enemy patrols, tank and machine gun positions, the exhausted and footsore men, some of whom had lost their helmets, could still grin and fight. One of the most noteworthy efforts at St Vith was the leadership of Col Thomas J. Riggs Jr (Huntington, WVa) commanding the 81-ECB. Once a midshipman at the US Naval Academy, Col Riggs first won fame as an All-America fullback at the University of Illinois. On the morning of December 17, Col Riggs took over the defense of the town. He disposed his limited forces, consisting of part of his own battalion; the Defense Platoon, 106th Hq Co, and elements of the 168-ECB, and waited for the coming blow. The wait was short. Soon a battalion of German infantry attacked behind armored vehicles and tanks. Time after time more tanks and infantry tackled the engineer line, probing for a weak spot. During these attacks, Col Riggs was in the center of the defense, rallying his men and personally heading counter-thrusts to keep the enemy off balance. Col Riggs was captured while leading a patrol in the defense of St Vith. Marched across Germany, he escaped near the Polish border and made his way to the frontier.

He was sheltered three days by civilians and then joined an advancing Red Army tank outfit. After fighting with it for several days, he was evacuated to Odessa and from there was taken to Marseilles. He rejoined the 81st in the spring when it was stationed near Rennes, France.

He was sheltered three days by civilians and then joined an advancing Red Army tank outfit. After fighting with it for several days, he was evacuated to Odessa and from there was taken to Marseilles. He rejoined the 81st in the spring when it was stationed near Rennes, France.

Ruthless concentrations of German artillery, armor and infantry were thrown against the 81-ECB on the eastern approaches to St Vith. In the meantime, the Headquarters Defense Platoon was making a heroic stand in an attempt to protect the CP. Cpl Lawrence B. Rogers (Salt Lake City, Utah), and Pfc Floyd L. Black (Mt. Crab, Ohio), both members of the platoon, along with two men whose identity never was learned, successfully held a vital road junction against three Mark V Panther tanks supported by infantry. With a machine gun, rocket launcher, two rifles and a carbine, the four-man volunteer rear-guard stopped the advancing force. They held the enemy at bay for two and a half hours, retreating only when their machine gun failed to function.

Ruthless concentrations of German artillery, armor and infantry were thrown against the 81-ECB on the eastern approaches to St Vith. In the meantime, the Headquarters Defense Platoon was making a heroic stand in an attempt to protect the CP. Cpl Lawrence B. Rogers (Salt Lake City, Utah), and Pfc Floyd L. Black (Mt. Crab, Ohio), both members of the platoon, along with two men whose identity never was learned, successfully held a vital road junction against three Mark V Panther tanks supported by infantry. With a machine gun, rocket launcher, two rifles and a carbine, the four-man volunteer rear-guard stopped the advancing force. They held the enemy at bay for two and a half hours, retreating only when their machine gun failed to function.

T/5 Edward S. Withee (Torrington, Conn) 81-ECB, volunteered for what seemed to be a suicidal mission. His platoon was pinned down in a house near Schönberg by four enemy tanks. All were doomed unless escape could be made while the enemy’s attention was diverted. Withee attacked the four tanks and the supporting infantry, armed only with a sub-machine gun. His platoon withdrew safely. When last seen, Withee was pouring fire into German infantry. He was listed as missing in action until April when he turned up in a PW camp. He was awarded the DSC.

T/5 Edward S. Withee (Torrington, Conn) 81-ECB, volunteered for what seemed to be a suicidal mission. His platoon was pinned down in a house near Schönberg by four enemy tanks. All were doomed unless escape could be made while the enemy’s attention was diverted. Withee attacked the four tanks and the supporting infantry, armed only with a sub-machine gun. His platoon withdrew safely. When last seen, Withee was pouring fire into German infantry. He was listed as missing in action until April when he turned up in a PW camp. He was awarded the DSC.

There was the magnificent bluff of 220-pound Capt Lee Berwick (Johnson’s Bayou, La) 424-IR. He talked 102 Germans and two officers into surrendering an almost impregnable position to a handful of men. He boldly strode to the very muzzle of enemy machine guns to warn of the huge force supporting him and ordered the senior officer to surrender. It worked!

There was the magnificent bluff of 220-pound Capt Lee Berwick (Johnson’s Bayou, La) 424-IR. He talked 102 Germans and two officers into surrendering an almost impregnable position to a handful of men. He boldly strode to the very muzzle of enemy machine guns to warn of the huge force supporting him and ordered the senior officer to surrender. It worked!