Document Source: Advanced Infantry Officers Course. Operations of the Regimental Pathfinder Unit, 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division in Normandy, France, June 6, 1944. Personal Experience of a Regimental Pathfinder Leader, Capt John T. Joseph.

Foreword: This is exactly the kind of archive I hate because there are no combat photos available to illustrate the text. I will see what I can do to avoid this photo problem. This archive covers the operation of the 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, Pathfinder Team in Normandy, June 6, 1944. A clear picture of Pathfinder operations can best be obtained by reviewing briefly the organization, development, and early experiences of Pathfinder Teams.

Combat difficulties that put the spotlight on the need for Pathfinder troops first appeared in the invasion of Sicily in July 1943. The 82nd Airborne Division was assigned the mission of seizing and holding one of the principal Sicilian Airfields and assisting in the amphibious landing of the US 1st Infantry Division. Two airborne battalions dropped thirty miles from their designated drop zones. Another battalion jumped fifty-five miles from its objective and fought with the British forces for six days. A fourth battalion, coming in on D+1, lost twenty-three of its troop carriers to Friendly Allies AAA fire (Source Capt Fred E. Perry). Although Pathfinder teams were not used during the Sicilian operation, training of advanced airborne parties had been initiated by the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion at Oujda (Morroco), in March 1943. Here, the Pathfinders were organized as a Parachute Scout Company, consisting of three platoons, each platoon having two squads of eight men. The mission of the Parachute Scout Company, as envisioned at this time, was to precede the main body of airborne forces to the designated areas of the initial invasion and by the use of Aldis Lamps (high-powered lights that could be seen at a considerable distance), flares, and smoke pots, to mark off drop zones for parachutist and landing zones for gliders. (Source Capt Fred E. Perry)

Combat difficulties that put the spotlight on the need for Pathfinder troops first appeared in the invasion of Sicily in July 1943. The 82nd Airborne Division was assigned the mission of seizing and holding one of the principal Sicilian Airfields and assisting in the amphibious landing of the US 1st Infantry Division. Two airborne battalions dropped thirty miles from their designated drop zones. Another battalion jumped fifty-five miles from its objective and fought with the British forces for six days. A fourth battalion, coming in on D+1, lost twenty-three of its troop carriers to Friendly Allies AAA fire (Source Capt Fred E. Perry). Although Pathfinder teams were not used during the Sicilian operation, training of advanced airborne parties had been initiated by the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion at Oujda (Morroco), in March 1943. Here, the Pathfinders were organized as a Parachute Scout Company, consisting of three platoons, each platoon having two squads of eight men. The mission of the Parachute Scout Company, as envisioned at this time, was to precede the main body of airborne forces to the designated areas of the initial invasion and by the use of Aldis Lamps (high-powered lights that could be seen at a considerable distance), flares, and smoke pots, to mark off drop zones for parachutist and landing zones for gliders. (Source Capt Fred E. Perry)

Further Pathfinder work was undertaken at Agrigento (Sicily), in August 1943, shortly after the completion of the Sicilian Campaign, through the efforts of Col James M. Gavin, Commanding Officer of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, and Col Joel L. Crouch, A-S of the 62nd Troop Carrier Wing. Col Charles Billingslea, former Commandant of the Airborne Training Center at Oujda (French Morroco), and chiefly responsible for the work of the Parachute Scout Company there, was placed in direct charge of the organization and training of the Pathfinder units. The 504-PIR, 505-PIR, and the 507-PIB each sent three Pathfinder teams to Agrigento for indoctrination in these new Pathfinder methods. In this new plan, pathfinders dropped ahead of airborne invasion forces to set up radar apparatus, radio beacons, and other improved locator aids. The training was greatly accelerated due to the imminence of the invasion of Italy.

On September 13, 1943, the 504th Pathfinder Team took off from Agrigento (Sicily), in planes flown by combat-seasoned pilots. With good piloting and dead reckoning navigation the Pathfinder team hit the designated drop zone, south of Paestum (Italy), without error. Radar, radio beacon, and other locator equipment were set up immediately. Twenty-five minutes later the first planes of the 504-PIR’s main body came directly over the drop zone. Within one and one-half hours ninety plane loads of men and equipment had been accurately dropped. The 506-PIR met with equal success. Both units were dropped in this area to fill a gap existing in the Allied lines. The Pathfinder team of the 509-PIB parachuted into their drop zone in the vicinity of Avellino (Italy) and guided the main elements into the exact area. Eureka could not be employed by the 509-PIB team due to the fact that planes used in dropping this battalion were not equipped with idle necessary Rebecca sets. With the employment of the ‘5-C’, a British Radio Beacon, men were dropped on small flat areas surrounded by mountains rising sharply to altitudes of three thousand feet. This made it necessary to jump the troops at slightly more than three thousand feet.

The 504-PIR and the 505-PIR Pathfinder groups used gasoline drums to mark their drop zones. This innovation, in addition to locating the drop zone for the main elements, indicated the direction of the wind. Other equipment, except for the absence of Rebecca-Eureka sets in the 509-PIR drop, that was used in the training phase at Agrigento (Sicily). This operation proved conclusively that Pathfinder teams were essential to the success of future airborne invasions. Out of 262 planes, 260 dropped their troops on the predesignated targets, a tremendous improvement over the Sicilian Campaign. This operation proved conclusively that Pathfinder teams were essential to the success of future airborne invasions. Out of 262 planes, 260 dropped their troops on the predesignated targets, a tremendous improvement over the Sicilian Campaign.

The eyes of higher commanders began to open to the obvious advantages of employing Pathfinder teams in future airborne operations. A directive from Headquarters, European Theatre of Operations, dated March 13, 1944, established eighteen Pathfinder teams in each airborne division. Two such teams were allotted to a battalion. Each team consisted of one officer and nine enlisted men, reinforced by security personnel. In the procedure outlined by the directive, the Pathfinder teams were to drop thirty minutes prior to the arrival of the first serial of the main elements. The thirty-minute interval was involved in mutual agreement between Airborne and Troop Carrier commanders. In the event that the Pathfinder team was neutralized by enemy action a second Pathfinder team, arriving with the first serial was prepared to organize the drop zone. In order to coordinate operations to a maximum degree the Air Corps was directed to furnish a provisional Pathfinder group to train with the airborne personnel. The Signal Corps was given the responsibility of supply and maintenance of special signal equipment (Eurekas AN-PPN-1, Halophane lights, flares, and cerise panels) to be employed by the Pathfinder teams.

The eyes of higher commanders began to open to the obvious advantages of employing Pathfinder teams in future airborne operations. A directive from Headquarters, European Theatre of Operations, dated March 13, 1944, established eighteen Pathfinder teams in each airborne division. Two such teams were allotted to a battalion. Each team consisted of one officer and nine enlisted men, reinforced by security personnel. In the procedure outlined by the directive, the Pathfinder teams were to drop thirty minutes prior to the arrival of the first serial of the main elements. The thirty-minute interval was involved in mutual agreement between Airborne and Troop Carrier commanders. In the event that the Pathfinder team was neutralized by enemy action a second Pathfinder team, arriving with the first serial was prepared to organize the drop zone. In order to coordinate operations to a maximum degree the Air Corps was directed to furnish a provisional Pathfinder group to train with the airborne personnel. The Signal Corps was given the responsibility of supply and maintenance of special signal equipment (Eurekas AN-PPN-1, Halophane lights, flares, and cerise panels) to be employed by the Pathfinder teams.

If you are interested, there is a copy of the original 1944 Technical Manual about Eureka AN-PPN-1A as used in Normandy in June 1944. Feel free to download the manual or read it online. EUCMH.COM-(TM-11-1140A-1944)-EUREKA AN-PPN-1A

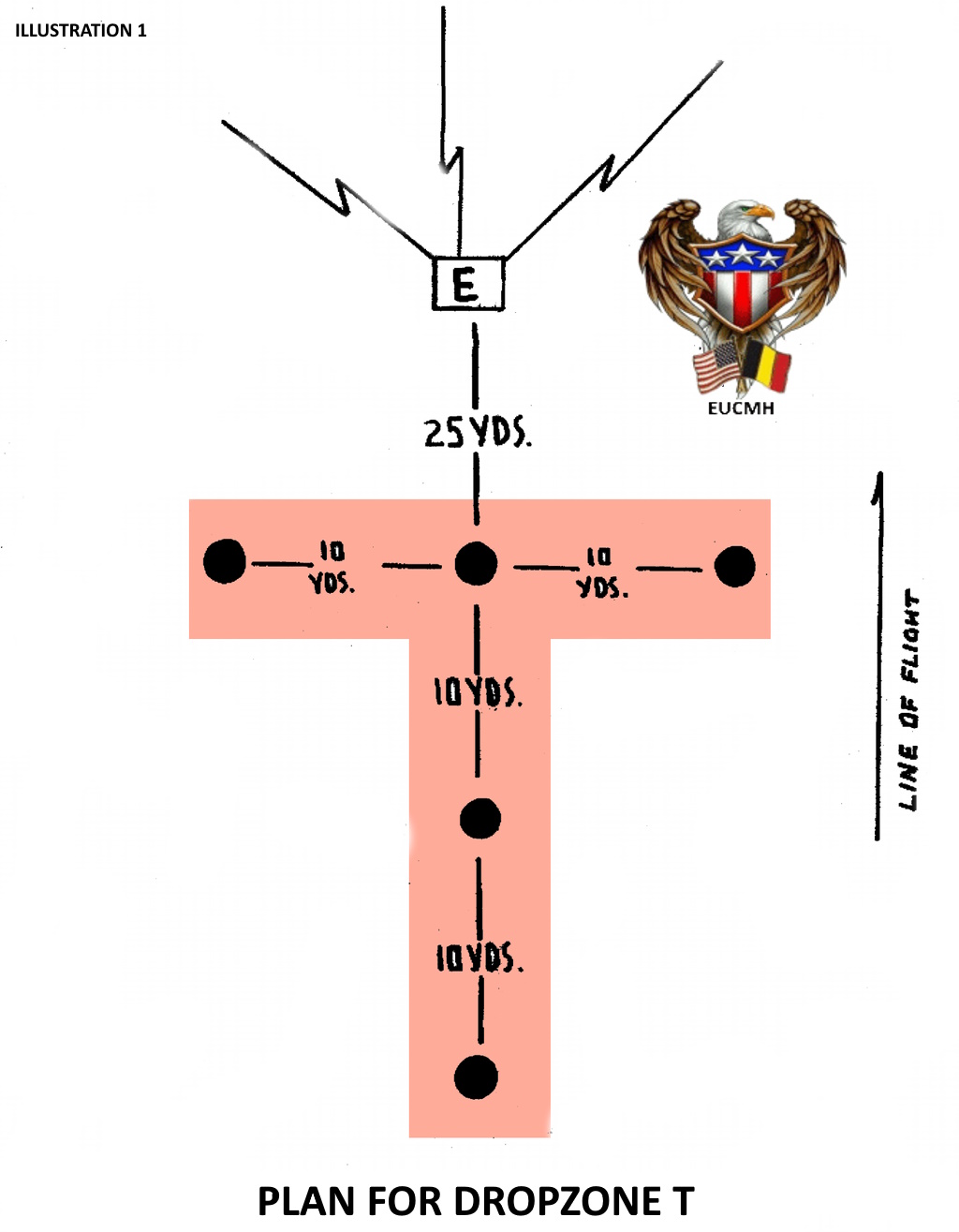

The marking of the drop zone (Paratroopers) was to be accomplished by placing five lights in a T arrangement, with a Eureka above the head of the T. This equipment was to be placed on the ground according to the size and shape of the drop zone and the speed and direction of the wind so that the GO signal could be given when the lead plane was directly over the head of the T. Distances between lights and Eureka are shown in illustration #1.

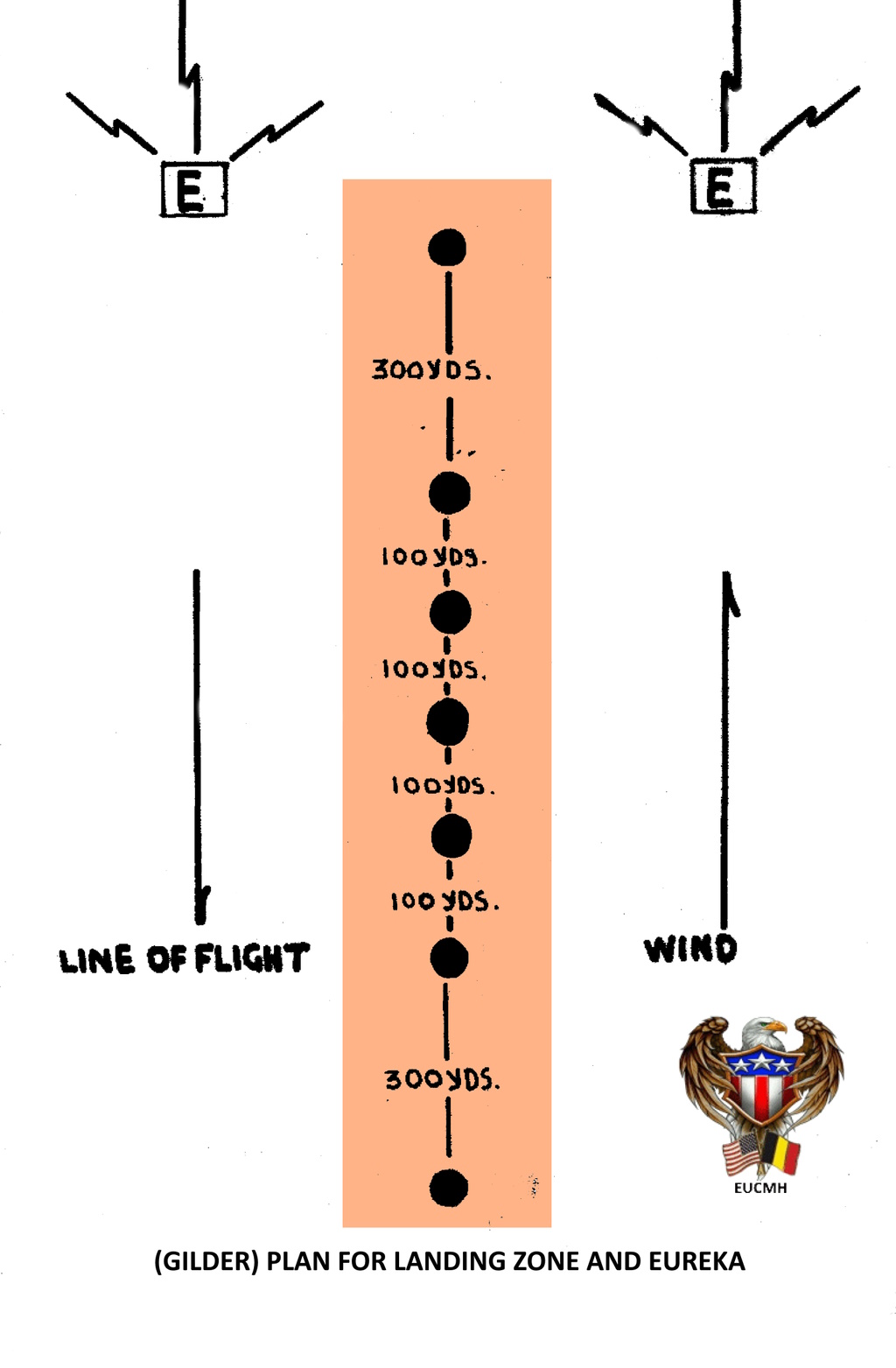

Landing zones for Gliders were to be marked as shown in illustration #2. For operations during daylight hours, cerise panels and M-16 colored smoke hand grenades or a combination of both were to be used in marking drop zones and landing zones. Daylight aids were to be spaced in the same manner as the night aids shown in illustrations number 1 & 2. Pathfinder planes were to be navigated by dead reckoning, maps checked by Radar aids, and special drop zone and landing zone aerial photographs.

Training for Normandy

As a result of the European Theatre of Operations directive formally establishing Pathfinders in Airborne divisions, the 505-PIR, the 507-PIR, and the 508-PIR, of the 82nd Airborne Division, each sent six officers and fifty-four enlisted men to North Witham (England) for training with the Ninth Troop Carrier Command Pathfinder Group (Provisional). Personnel from the 82nd Airborne Division formed a Provisional Pathfinder Company. All potential Pathfinders were hand-picked from a large group of volunteers. Training consisted mainly of practical work – dropping with equipment and organizing drop zones and landing zones for Airborne operations. Special emphasis was placed on night operations. As training progressed new ideas and practices were developed. A Standing Operating Procedure was set up to control the training and insure coordinated action in combat. The strength of the Pathfinder team was changed to two officers and twelve enlisted men (Team Leader, Assistant Team Leader, Light Section Leader, seven light men, two Eureka operators, and two assistant Eureka operators). Instead of the two Pathfinder teams per battalion originally envisioned each battalion group was streamlined to one team. Three Pathfinder teams, each representing a battalion of one regiment, were flown to a drop zone in three planes flying in a tight V formation. All Pathfinder troops dropped on the approximate center of a jump field.

Immediately after assembly on the ground the Regimental Pathfinder Leader (usually the senior officer, who was also in command of a Battalion Pathfinder team) selected the location for the T of lights carried by his team and ordered them set up. Simultaneously he dispatched the two remaining teams to their general locations, one forward and one to the rear of the base position. The distance between Ts was usually about 700 yards. As the teams moved away from the base position the Light Section Leader laid assault wire, each team set up its lights and Eurekas and installed sound-powered telephones so that voice communication was available between the battalion teams and the Regimental Pathfinder Leader. The Regimental Pathfinder Leader controlled the use of navigational aids by telephone. This permitted the dropping of each Battalion on different sections of the drop zone without losing control and aided considerably the problems of assembly. The Regimental Commander was certain (assuming the Pathfinders were able to complete their missions) of having communication with his Battalion Commanders at the very outset of the operation. The organization of a Regimental drop zone is shown in illustration #3.