January 14, 1945 The attack began at dawn according to plan. In one dash the combat team reached the patches of forest, dismounted, and pushed gleefully southwestward through the woods. During the morning it was learned that, for reasons still unknown today, the 9.PD had not begun to attack. As a result, the combat team met infantry fire and increasingly well-aimed artillery fire from the deep right flank and had to defend itself against flanking counterthrusts. Thus the attack had become futile and had to be determined. The combat team retreated from the forest after suffering considerable losses from shells detonated in the treetops. Throughout the day and established defense positions southwest of Oubourcy against enemy counterattacks. During these operations, the brigade came under the command of the LVIII Panzer Corps. This corps ordered another combat team consisting of the 2.Battalion and two panzer companies to Derenbach as reserves for the 1.SS-PD. The panzer battalion of the brigade was drawn up to Hamiville as Corps reserve. Since this separation threatened to dissolve the brigade, I visited FM Walter Mödel to point out my personal written order from the Fuehrer which stated that my brigade was to be employed only as a whole unit. I was assured this would be done.

January 15, 1945 In the afternoon the brigade received orders from the LVIII Panzerkorps to prepare for defense in the sector bounded by the crossroads 1000 Meters southwest of Moinet, the height east of Longvilly, and the western edge of Oberwampach. The brigade was to establish an effective block on the road from Bastogne to Clervaux. During the night the 1.Battalion deployed north of the road, and the 2.Battalion south of the road, and the 3.Battalion had been disbanded after heavy losses in personnel. The artillery battalion moved into position in the Crendal area; the flak regiment was committed for both air and ground defense on both sides of the road east of Allerborn. The bulk of the panzer regiment was in Hamiville, with elements in Allerborn. An assault gun company had been attached to each of the battalions committed at the front. The advanced command post of the brigade was at Baraques de Troine (Troine-Route), 1000 M northeast of Allerborn. On the right was the 167.VGD, on the, left the 5.FJD. Recon during the night reported contact with the enemy at Longvilly.

January 16-18, 1945 These days were marked by numerous enemy attacks on both sides of the road. On the whole, these were successfully countered. The main burden was borne by the infantry and panzer troops, who often had to counterattack several times a day. Almost superhuman performances were demanded particularly of the infantryman who, in his foxhole day and night without relief, was wet to the skin from the almost continuous snowdrifts. Second and third-degree frostbites increased alarmingly. With recon reports indicating US forces opposite us, the customary relief for the night was impossible because of a lack of reserves. The trench strength of the companies fluctuated at that time between 10 and 15 men each. An assembly of enemy tanks just north of Longvilly was observed at dawn on January 16. It was crushed by two assault guns, which during the fueling had been moved up to the firing range without being noticed. Eleven of the enemy tanks were put out of action. This blow, which caused panic in the enemy camp, could not be exploited because the battalion in the area was still occupied with establishing a defense position and no other forces were available at that time. An enemy attack that temporarily reached the crossroads south of Moinet collapsed under combined heavy flak and artillery fire. A particular source of concern to the brigade was the contact with its left neighbor, the weak 5.FJD, which had relieved the 1.SS-PD on January 15. Whenever the enemy penetrated at Oberwampach, part of the panzer regiment attacked either via Allerborn or Derenbach. Here, too, the situation could frequently be improved. The part of the flak regiment employed in air defense reported two to three downed enemy airplanes daily. Consequently, the frequency of low-ranged air attacks over the brigade area began to drop substantially. This occurred repeatedly during the Ardennes Offensive.

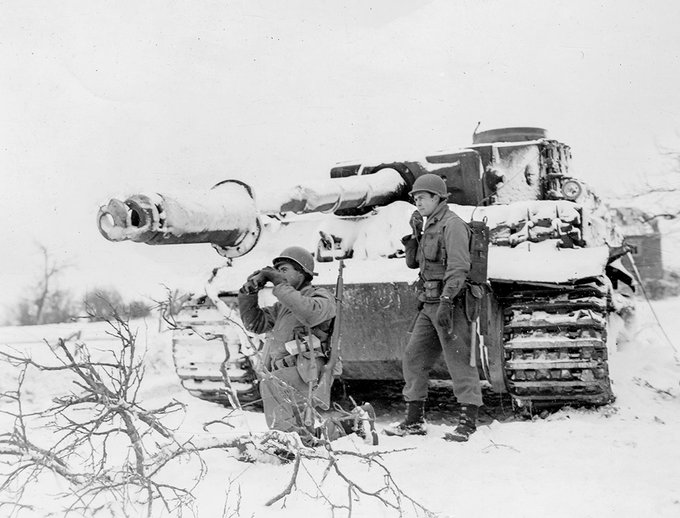

January 19-20, 1945 The front was retracted by approximately 2500 Meters as a result of enemy penetrations against the unit on the left. The new position roughly along the old tank intercepting position, the international frontier west of Troine – the western edge of Baraques de Troine, the western edge of the woods east of Allerborn – alignment of the road to Derenbach. In addition, elements of the Fuehrer Grenadier Brigade and about 10 Tiger tanks (Panzer VI) of the 9.PD was given to the brigade. The brigade’s mission was to block the road effectively under all circumstances to ensure a smooth withdrawal by the units of the army committed farther north. In the new line, all dispensable soldiers in the brigade supply trains and all dispensable gunners of the flak regiment were given infantry assignments. The completely exhausted elements of 1. and 2.Battalions were transferred to the Deiffelt, Doennange, and Lullange areas for 24 hours to sleep and dry their clothes. The artillery battalion moved into position in the Donnange area, the panzer group transferred to Wincrange. The units from the Fuehrer Grenadier Brigade and the 9.PD was detached again. Enemy attacks on January 19 and 20, were readily repulsed; often observed assemblies in the Allerborn were fired upon by the artillery.

January 21, 1945 A new Main Line of Resistance (MLR) was now occupied, running from the western edge of the woods east of Crendal in Luxembourg via the western edge of Winncrange and the western edge of Boevange to the hill belt south of Boevange. All enemy attacks here were also repulsed without the assistance of the armored group in the Doennange area. The Brigade command post was at Eselborn, Luxembourg.

January 22, 1945 The Fuehrer Escort Brigade moved into a bridgehead position around the Eselborn and Weicherdange in Luxembourg to cover the withdrawal of the divisions of the LVIII Panzer-Corps east of the Clerve River, in Luxembourg. The artillery battalion was ordered into the Reuler area east of Clervaux, Luxembourg for guard duty. The heavy battalion of the flak regiment was committed in the Marnach area; the light battalion was stationed at the crossing points of the Clerve River for air defense. The bulk of the panzer regiment was transferred east of the Clerf sector. To each of the battalions committed in Eselborn and Weicherdange, an assault gun battery was assigned. The roads leading to the Clerf sector were prepared for demolition.

January 23, 1945 Orders from the army group transferred the brigade to the army group reserve. The brigade moved into the area south of Arzfeld, Germany via Clervaux – Marbourg (Luxembourg) – Dasburg – Daleiden, Germany. On January 24, 1945, I learned in a visit by the Fuehrer’s adjutant that the brigade was to be expanded rapidly into a panzer division. The additional units had already been assembled. I received orders to go to Berlin, first to report to the Fuehrer, and secondly to manage the rehabilitation and reassembly of the brigade as a division. Within a short time, the brigade was to be shipped by train for commitment in the Eastern Front. The newly attached units were to be conducted in the unloading area.

The loss of personnel amounted to almost 2000 men, about 450 of which were killed. A large number of the wounded recuperated and returned to their units during and immediately after the offensive. About 60 to 70 percent of the casualties were the result of artillery shells splinters. The concentrated, flexible artillery fire of the enemy was most feared by the troops. About 15 to 20% of the losses were caused by bombs and low-altitude air attacks. These losses were inflicted on supply trains and reserves rather than on the fighting troops. The brigade could successfully protect itself from air attacks by its own strong antiaircraft forces. Of the slight losses among the fighting troops 5 percent were missing in action, approximately 10% were caused by tank fire, and the rest by infantry fire. Of nine commanding officers, three were killed and injured. Of the approximately 100 tanks and assault guns originally available, the brigade had 25 to 30 in usable condition after the offensive. Ten to twelve underwent short-term repairs and about fifteen long-term repairs, making a total of 55 to 60%. Ten to twelve tanks were put out of action by enemy antitank guns or tanks, five to ten ran into mines, and the rest had to be destroyed during the fighting either because they lacked fuel or there were not sufficient wreckers. There was no notable help from the army or army group. The artillery lost two of its ten light guns: one was run over by a tank, and the other was hit directly by artillery fire. Of the four heavy guns, one dropped out as a result of a direct bomb hit during the march. The heavy flak battalion lost three of its twenty-four heavy guns, two through tank action, and one through bombing. Of the 135 armored personnel carriers, about 45 were lost, mostly as a result of artillery action. A large number had to be demolished for lack of wreckers. In the rear area, the brigade lost a relatively high number of supply trucks as a result of fighter-bomber attacks.

On the other side, a total of 140 to 150 enemy tanks were put out of action or captured. Before we had to destroy our own tanks when we abandoned the territory we had gained, the ratio of our losses to the enemy’s was one to eight. A striking feature was the relatively large number of vehicles we captured in unimpaired conditions. In all the brigade captured 60 to 70 jeeps and about the same number of trucks. But the joy was short-lived because these vehicles consumed too much fuel. They were either destroyed by us or turned over to other units. Of sixteen downed planes, thirteen were credited to the flak battalion, and three to infantry units. About 450 prisoners were taken. Twenty to thirty guns were captured or destroyed. No notable enemy fuel stocks fell into our hands though fuel-finding details always accompanied the fighting troops. On the other hand, considerable amounts of food, clothing, and all kinds of equipment were secured. The Brigade lived almost exclusively on captured items.

Brigade Fuel Situation As far as I remember, 4.2 daily issues of fuel were planned. (1 daily issue corresponded to 1 Time Fuel/1 Vehicle/100 KMs Travel). When the brigade began its advance out of the Daun (Germany) area on the third day of the offensive, it had only two daily issues. At that time the entire transportation section had been dispatched four days previously to receive the allocated fuel. I believe that at the time the fuel had to be picked up far in the rear in the vicinity of the Rhine River. All the allocated fuel was probably never received. Throughout the offensive, individual vehicles arrived sporadically at the front, but never whole convoys. The brigade had continuous fuel difficulties after December 20 and most of the tactical decisions were dependent on the fuel situation. Furthermore, because of road congestion and bad road and terrain conditions, the troops needed far more fuel than was usually allocated under normal circumstances.

During the transfers, for example from La Roche en Ardenne to Bastogne, occasionally 50% of the vehicles had to be towed. Since the distance from the fuel issuing points to the field units was always very great, continual delays and losses of vehicles had to be anticipated as a result of fighter-bomber attacks and road congestion. On some days as many as half of all fuel vehicles were set aflame even though they could not be recognized as such vehicles. Another drawback was the seizure, carried out inconsiderably by some agencies, of approaching fuel for allegedly decisive purposes. Enemy fuel depots were captured, but they provided only a temporary supply. It was established procedure to pump fuel from the tanks of captured vehicles.

Failure of the Offensive The beginning of the Ardennes Offensive was chosen for a period when an overcast sky was expected. This was done to eliminate as far as possible enemy action from the air in view of our own aerial inferiority. This factor was even more important because the supreme command had selected the Eifel region, which, as an assembly and combat area, presented the difficulty of channeling heavy traffic through relatively few roads. Contrary to all weather forecasts, the sky cleared after the first week, at a time when the fighting divisions and those following closely behind were dependent on the poor road network.

Road Conditions Road conditions, particularly in the already snow-covered areas, worsened as a result of new snowfall. A majority of the divisions, as well as the Fuehrer Escort Brigade, had no winter equipment for their vehicles, particularly for the tanks. As an example, at St Vith the chaotic traffic conditions in the snow-covered terrain made it impossible to commit a mobile panzer unit such as the Fuehrer Escort Brigade in time, even allowing for the deficient technical driving experience of a young unit. Aside from bad road conditions, it was impossible from the command you point to launch a panzer unit on a road which at places could be used only in a single file. Moreover, the entire road was required by the horse-drawn 18.VGD, which was just moving up toward the front. Columns of the 6.Panzer-Army was also using it. Yet I was ordered to advance along this road from Roth via Auw and Schoenberg to St Vith. At least one of the higher headquarters should have ordered the roads to be cleared temporarily by military police forces. Or the delay necessary to allow the 18.VGD to move up should have been accepted and the Fuehrer Escort Brigade ordered to delay its advance until afterward. In either case, considerable time would have been saved.