During the campaign, Mars was introduced to combat use, the night sighting devices known as Snooper Scopes and Sniper Scopes. These were received in the midst of operations and hasty acquaintance with the instruments were all that could be had. Tactics were established for the use of these on the ground. At the conclusion of this campaign, the Mars Task Force was a well-knit and experienced force, all elements having undergone combat, new techniques devised, lessons learned, morale high, and leadership seasoned.

Against increasing resistance from the Japanese 33-A, Sultan’s forces moved south from Myitkyina with the British 36-ID to the west, the Chinese 50-ID in the center, and the Chinese 30 and 38-IDs along with the Mars Task Force in the east. At the same time, the Chinese Expeditionary Force drove west toward the town of Wanting on the China-Burma Border. Although the 33-A’s defensive positions along the border separated the two converging forces, the Japanese were greatly outnumbered and no match for Sultan’s men. By late January the Japanese 33-A was forced back, Wanting was captured, and the land route to China was restored to Allied control. Accompanied by the press and public relations personnel, engineers, and military police, the first convoy was pushed off for China from Ledo on January 12, 1945. After being delayed by fighting en route, the vehicles rolled triumphantly into Kunming on February 4. The opening of the Ledo Burma Road, soon to be redesignated the Stilwell Road by Chiang Kai-shek, forged the last link in the chain of land communications between Calcutta and Kunming, a distance of more than 2000 miles. By the month of July, gasoline also would be pumped through a pipeline constructed from Ledo to Kunming, 928 miles away, paralleling Stilwell Road.

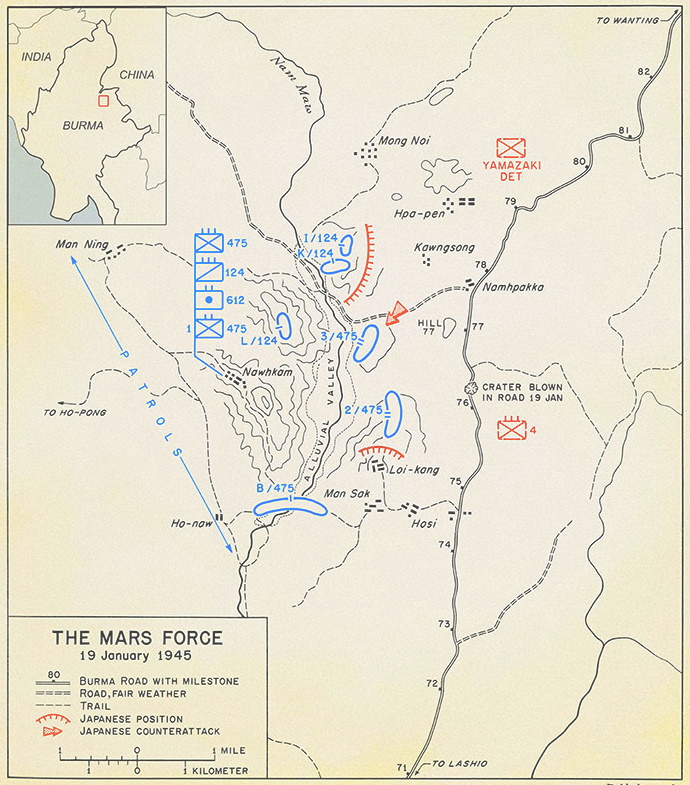

Sultan next considered how to deal with the Japanese forces in north-central Burma who were still near enough to disrupt road traffic moving into China as well as to threaten the flank and rear of British forces now driving into central Burma. Believing that a threat to the Japanese supply line, the old Burma Road which ran from the Chinese border south to Lashio and Mandalay, would result in Japanese withdrawal, Sultan ordered Gen John P. Willey (Mars Task Force Commander), into action. He wanted the Mars force, less the 1st Chinese Regiment, which was held in reserve, to move overland around the Japanese defenses and cut the road near the village of Ho-si, about thirty miles south of Wanting. Willey’s projected route was suitable for resupply by air, long recognized as the key to success while operating behind enemy lines, but the overall plan had disadvantages. In the objective area, the Burma Road was not easily severed, since it was beyond machine gun range from the ridge paralleling the road on the west and secondary roads existing in the hills to the east, providing the enemy with an alternative line of communication. Nevertheless, Willey’s troops executed their part of the operation, reaching the vicinity of the Burma Road on January 17.

While Willey’s Task Force soldiers took up position, Sultan pushed the battle-hardened Chinese against the Japanese 33-A’s 56-ID which was holding defensive positions south of Wanting. The Chinese 38-ID moved southeast, astride the old Burma Road, while the Chinese 30-ID struck out across the country, swinging south and east toward the road about ten miles north of Ho-si. Further south and west, the Chinese 50-ID and the British 36-ID continued moving south toward the road between Lashio and Mandalay, an area held by the Jap 33-A’s 18-ID. The 56-ID’s commander, Gen Yuzo Matsuyama, recognized his perilous situation. Obviously, the immediate threat came from the north and northwest. But should the Sultan’s command, which Matsuyama placed at 6 divisions, be seconded by the entire Chinese Expeditionary Force of 14 divisions crossing into Burma from the east, his 20.000 men would be vastly outnumbered. When a large airdrop of supplies came in for the Mars Task Force, the Japanese mistakenly thought that an airborne force was being landed. Convinced that he would soon be cut off, Matsuyama informed the 33-A’s commander, Gen Masaki Honda, that his situation was critical and that he planned to destroy the bulk of his ammunition and abandon his present positions.

Honda, however, viewed Matsuyama’s situation differently. He instructed Matsuyama to defend in place until casualties and ammunition could be evacuated. Then he sent two motor transport companies, about forty vehicles loaded with gasoline, to join the 56-ID and assist in its final withdrawal. Encouraged by additional supplies, Matsuyama evacuated most of his casualties and several tons of ammunition before parts of the Chinese 30 and 38-IDs blocked the passage on the road north of Ho-si on January 29. That night a sudden and violent banzai charge against the roadblock quickly overran the Chinese position. When the Chinese made no move to reestablish the block, Matsuyama began a retreat after dark on January 31, almost in front of Chinese and American forces massed west of that section of the Burma Road. The move was risky but the Japanese troops successfully completed their withdrawal by February 4.

At this juncture, Allied inaction was puzzling. Willey had positioned him in two largely untried American regiments near Ho-si. There, rather than occupy a blocking position squarely astride the Burma Road and risk-taking heavy casualties, he limited his effort mainly to interdicting the road with artillery and mortar fire. His infantrymen had dug in along a ridge about a mile and a half west of the road, with the 124-CAV to the north and the 475-IR to the south. Since arriving in the area on January 17, they had experienced several small engagements with enemy forces and had managed to disrupt traffic on the road to their east, although the Japanese fuel convoy had managed to reach Matsuyama’s troops to the north. In fact, Willey’s men remained unaware that Japanese forces were withdrawing from the area using the trails and roads east of the main highway.

On February 2, the 124-CAV attacked what was thought to be a Japanese battalion entrenched on the high ground near the village of Hpa-pen, about a mile and a quarter northeast of the regiment’s foxholes. Willey believed that the capture of this position would make it easier for the 124-CAV to stop Japanese traffic along the Burma Road. Unknown to the Americans, however, the Japanese eastern bypass around the Burma Road in front of the position of the Mars Task Force began near Hpa-pen and was strongly defended. After a twenty-minute artillery and mortar preparation, the 2/124-CAV moved out at 0620 toward Hpa-pen with Troops E and F abreast and Troop G in the rear. As Troop F moved up a rough trail, its commander, Lt Jack L. Knight, was well out in front when two Japanese suddenly appeared, Knight killed them both. Crossing the hill to the reverse slope, the troop commander found a cluster of Japanese emplacements. Calling up his men, he led them in a successful grenade attack. When the Japanese, who seemed to have been surprised, steadied and began inflicting heavy casualties, Knight kept his attack organized and under control. Although half-blinded by grenade fragments, bleeding heavily, and having seen his brother Curtis shot down while running to his aid, Knight fought on until he was killed while leading an attack on a Japanese emplacement. For this action, Lt Knight received the Medal of Honor posthumously, the only Medal of Honor awarded in the CBI theater during World War II.

On February 2, the 124-CAV attacked what was thought to be a Japanese battalion entrenched on the high ground near the village of Hpa-pen, about a mile and a quarter northeast of the regiment’s foxholes. Willey believed that the capture of this position would make it easier for the 124-CAV to stop Japanese traffic along the Burma Road. Unknown to the Americans, however, the Japanese eastern bypass around the Burma Road in front of the position of the Mars Task Force began near Hpa-pen and was strongly defended. After a twenty-minute artillery and mortar preparation, the 2/124-CAV moved out at 0620 toward Hpa-pen with Troops E and F abreast and Troop G in the rear. As Troop F moved up a rough trail, its commander, Lt Jack L. Knight, was well out in front when two Japanese suddenly appeared, Knight killed them both. Crossing the hill to the reverse slope, the troop commander found a cluster of Japanese emplacements. Calling up his men, he led them in a successful grenade attack. When the Japanese, who seemed to have been surprised, steadied and began inflicting heavy casualties, Knight kept his attack organized and under control. Although half-blinded by grenade fragments, bleeding heavily, and having seen his brother Curtis shot down while running to his aid, Knight fought on until he was killed while leading an attack on a Japanese emplacement. For this action, Lt Knight received the Medal of Honor posthumously, the only Medal of Honor awarded in the CBI theater during World War II.

With resistance heavy on Troop F’s front and with Troop E fighting off strong counter-attacks, the squadron commander committed his reserve, Troop G in mid-morning. Advancing through the first line of Japanese bunkers, the reserve troop momentarily paused to direct artillery fire on a second enemy defense line to its front and then charged forward to carry the final Japanese position on the hill. When the fighting ended, the Americans held the high ground close to the road and reported killing over two hundred of the enemy. The 2/124-CAV also incurred many losses. Twenty-two of its soldiers were dead and another eighty-eight had to be evacuated on litter because of wounds.

The next day, the 475-IR, still positioned south of the cavalry regiment, attacked a Japanese position on a ridge near the village of Loi-Kang about a mile west of the Burma Road. While the 2/475 moved north to fix the Japanese in position, the 1/475, preceded by an extensive artillery and mortar barrage, struck from the south, eventually clearing that portion of the ridge of all enemy defenders at a cost of 2 killed and 15 wounded. But by this time, most of the Japanese had escaped to the south. During the next few days, patrol actions and artillery exchanges with the Japanese rearguard and stragglers grew fewer. By February 10, when Chinese forces arrived in the Mars area in strength, seeking to regain contact with the Japanese 56-ID, the enemy had long since passed through and was fifty miles away regrouping at Lashio.

To the west, Gen Sultan’s Chinese 50-ID and British 36-ID continued moving south toward the Burma Road between Lashio and Mandalay. In early February, the British came up against strong resistance from the Japanese 33-A’s 18-ID. Fighting continued until February 25 when the 18-ID was ordered to move south to reinforce the 15-A defending against Gen Slim’s 14-A, which was closing in on Mandalay to the west. By the end of March, both the Chinese 50-ID and the British 36-ID had reached the Burma Road east of Mandalay, where the 36-ID came under Slim’s 14-A control. While Sultan was clearing the Japanese from the northern stretch of the Burma Road, Slim’s 14-A had continued to push the Japanese back in the center. The British 33rd Corps advanced southeastward until meeting stubborn resistance north of Mandalay in late January. Meanwhile, the British 4th Corps had slipped south undetected, and by February 19, had established a bridgehead on the Irrawaddy River about one hundred miles south of Mandalay. From there an armored column, completely supplied by air, smashed its way sixty miles eastward to capture the critical town of Meiktila and its cluster of eight airstrips. The drive to the east continued another twenty miles to the town of Thazi on the Mandalay Rangoon Railway, thereby cutting off some 30.000 Japanese troops to the north from their supplies and their best route of escape. The fighting around Meiktila and Thazi grew more severe as the Japanese Burma Area Army shifted troops from the Mandalay front southward and also rushed up reinforcements from southern Burma in an effort to reopen the route.

With the battered Japanese 15-A fully occupied with the threat to its rear, the British 33rd Corps resumed its advance on Mandalay, which it reached late on March 7. However, because of stubborn Japanese resistance, the city was not cleared for two more weeks. The 33rd Corps then continued its push southward until encountering enemy resistance from the hastily summoned Japanese 33-A, about eighteen miles north of Thazi. Despite substantial losses, the enemy was able to hold open an escape gap until the end of March. Even so, a considerable number of Japanese troops were trapped when the corridor finally closed. By the time Mandalay fell, combat in Burma for the Mars Task Force, the Chinese Expeditionary Army, and the X Force had come to an end. In March, the Chinese in Burma began to return to their homeland, and the Mars Task Force soon followed. Gen Wedemeyer, who had replaced Stilwell as the American commander in China, hoped to rebuild the Chinese armies using the Chinese divisions from Burma as a nucleus and the Marksmen as trainers and advisers. Using the revitalized Chinese units, he planned to fight his way to the coast by the fall of 1945. As for Gen Sultan in Burma, with all his regular combat units gone by June, he became concerned primarily with logistical support for the China Theater. His only ground combat force available to continue the fight against the Japanese was Detachment 101 of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

Formed in 1942, Detachment 101 supported Stilwell’s, and later Sultan’s, Northern Combat Area Command as an intelligence-gathering unit and as an organization for assisting in the return of downed Allied airmen to friendly lines. By the spring of 1945, however, Detachment 101, commanded by Col William R. Peers, had organized a large partisan force behind enemy lines in northern and central Burma. Reaching a peak strength of over 10.000 native Burmese Kachin tribesmen and American volunteers, the detachment operated as mobile battalions screening the advance of British and Chinese forces moving on Mandalay and Lashio. Completely supported by air, they employed mainly hit-and-run tactics and avoided pitched battles against better-trained troops. Detachment 101 operations were scheduled to end after regular troops secured the Burma Road south of Lashio. Although the Kachin guerrillas, many hundreds of miles from home, were told that their work would be finished then and that they could return to their homes, when the time actually arrived, the situation had changed.

OSS DET 101

The movement to China of the Chinese and American ground forces in Burma left the guerrillas as the only effective fighting force available to Sultan. Fifteen hundred Kachins volunteered to remain, and Peers was able to recruit an additional 1500 Karen, Ghurka, Shan, Chinese, and a few Burmese volunteers. Dividing his 3000-man partisan force into four battalions, he assigned operational sectors that extended from the Burma Road into southeast Burma for roughly 100 miles. Starting in April and extending into July 1945, Peers’ guerrilla units drove about 10.000 Japanese troops from this region. During that period all of the battalions saw heavy fighting. While most of the Japanese encountered were tired and poorly equipped, they habitually fought to the last man when pinned down. The partisans killed over 1200 of the enemy at a cost of 300 of their own.