The 56-CAV Brigade became an independent unit after leaving the 23-CAV Division on April 1, 1939. On June 30, Troops I and K of the new 3rd Squadron were organized at Corpus Christi and Seguin, respectively. The 3rd Squadron’s headquarters was organized in Houston almost a month later, on July 23. Between August 3 and August 23, the regiment participated in the Third Army maneuvers in the Kisatchie National Forest in Louisiana, involving 70.000 troops. On October 1, 1940, the 3rd Squadron headquarters was inactivated and Troops I and K became Troops C and G of the 1st and 2nd Squadrons, respectively. The 124-CAV was called up for federal service on November 18, at San Antonio. It was transferred to Fort Bliss, where it arrived on November 28. The 56-CAV Brigade became part of the Third Army upon Federalization. Headquarters and 1st Squadron transferred to Fort Brown on February 5, 1941, while the 2nd Squadron simultaneously transferred to Fort Ringgold. The regiment relieved the 12-CAV of the Fort Brown Command sector of the Mexican Border Patrol. The 124-CAV conducted border patrol duty along the Mexico-US border from Brownsville to Laredo. On May 29, the regiment returned to Fort Bliss. Between August 12 and October 2, it participated in the massive Second Army and Third Army maneuvers in the Louisiana Maneuver Area, which involved 342.000 troops. On October 4, after the maneuvers ended, the regiment returned to Fort Brown.

On Jun 5, 1942, Col John H. Irving became regimental commander. Between November 4 and December 22, 1943, the regiment was stationed at Fort Russell. At the beginning of May 1944, Irving was replaced for health reasons by Col Milo H. Matteson. The 124-CAV remained on the Mexican border with the 56-CAV Brigade until May 12, 1944, when they were moved to Fort Riley, the last horse cavalry regiment in the army. At Fort Riley, the regiment became part of 4-A. After turning in its horses, the regiment left Fort Riley on July 10, staging through Camp Anza to the Los Angeles Port of Embarkation, from which it departed aboard the transport USS Gen Henry W. Butner for Bombay, India on July 25. Arriving in India with 78 officers and 1522 enlisted men on August 26, the regiment was transported by rail to the Ramgarh Training Center, where it conducted infantry, jungle, patrol, and long-range penetration training. It was reorganized as the 124-CAV (Special) on September 20, after being officially dismounted. Five days later, the 3rd Squadron was activated in India by other regimental personnel after being reconstituted on September 20. The regiment became part of the newly activated 5332nd Brigade (Provisional), which became the Mars Task Force. As well as the 124-CAV, the task force also included the 475-IR, the survivors of the Merrill’s Marauders, brought up to strength by replacements from the USA, and the elite American-trained and equipped Chinese 1-IR (Separate). In October, the regiment was flown to Myitkyina, entering combat with the task force.

At no time was the brigade permitted to employ the Chinese 1-IR (Separate) in any tactical operations. To have been able to use this regiment would have increased the striking power of the brigade considerably. Although the Namhpakka Hosi Campaign is considered highly successful, another regiment would have permitted the use of either the 475-IR or the 124-CAV to swing southward or eastward in a brigade encirclement of the enemy. It was impossible to do so under the circumstances, for to use one or two battalion combat teams for this purpose would have jeopardized not only such a small striking force but also the holding force. The series of commanding terrain features were such that had they been left open by any battalion combat team it would have been an open invitation to the Japs to surround and destroy the brigade piecemeal. The Chinese 1-IR, later attached to the 50-ID, and committed, demonstrated its ability, and climaxed its campaign by securing Kyaukme and linking with the British 36-ID. This closed an east-west line, Mong Yai-Hsipaw Kyaukme Monglong-Mo-Gok. The British were thus placed in a position to turn to the southwest to join with the forces of the 14-A, to establish the line, Mong Yai-Hsipaw Kyaukme Namyo Mandalay, to terminate the conquest of northern and north-central Burma. The brigade component committed in the Tonkwa-Mo Hlaing sector (475-IR) broke the Jap opposition in that area and permitted the 50-ID to move in and occupy the area, thence to move southward to play its part in establishing the line mentioned above.

Upon completion of the action at Tonkwa, the brigade turned to the east and thrust deep into enemy territory to strike the Namhkam Lashio Burma Road axis, at Namhpakka. The swiftness of movement gained surprise, and the viciousness of attack removed the keystone of the sector. The blow inflicted by the Mars Group at this point caused the enemy to withdraw rapidly below Lashio and allowed the Chinese new 1-A to move almost unopposed south of Lashio, screening against counter-attack and forcing the enemy a safe distance from the Stilwell Road. The brigade was held in the

The training period of the Mars Group as a brigade was unusually short. One year is considered the normal training period for a division. Further, all of the brigade infantry units, as noted before, had to be either organized (475-IR) or converted (124-CAV, Chinese 1-IR Sep). Throughout tactical operations, the 612-FAB (Pak) and the 613-FAB (Pak) acquitted themselves with distinction. This was accomplished with the sole aid of 75-MM Pack Artillery, constantly opposed by much heavier and longer-range enemy weapons (105-MM and 150-MM). The basic intention of field artillery, to displace enemy artillery from hostile fire positions against our forces, could not be accomplished by the range and the striking power. However, in the long run, this was satisfactorily accomplished by attrition and by slow but effective destruction of enemy armament and materiel, as well as by disorganization and damage to motor parks, fuel dumps, warehouses, and CP (brought within range by the selection of objective). The inability to force the earlier displacement of enemy artillery resulted in numerous brigade casualties. To reach the brigade objectives, many difficulties previously believed to be well nigh impossible were overcome. That men, mules, and fighting equipment can be moved during the monsoons over mountainous Burma jungle trails as indicated. Three days of torrential rain, known as the Christmas monsoons came during this movement.

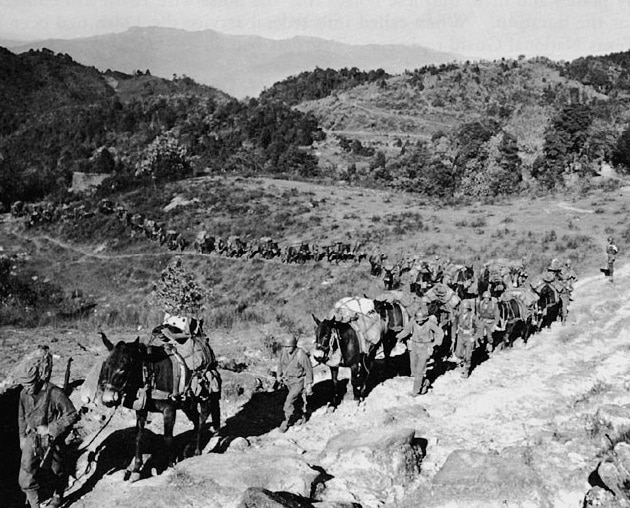

Trails became running streams of water; narrow paths lacing the edges of the mountain ranges became slippery deathtraps. Necessarily, some mule loads were thrown and animals plunged headlong off trails, but approximately 3000 mules and 7000 men performed the entire movement with the loss of no more than three mule loads. Often mules were hoisted by rope and the load was recovered in the same manner. It is a signal tribute to the mule leaders who so successfully nursed their hardy charges through these difficulties. Although previous training of the mules had been along with herding principles, the brigade system of a mule leader to each mule paid rich dividends. Perimeter defense was securely established each night and wide recon patrols were kept active.

In the movement from Nansin to Namhpakka, topography was unfavorable. Forbidding ranges were traversed. Above the Schweli River, these were sometimes so exhausting as to permit only one or two minutes of moving, followed by five minutes of rest. Terrain permitted, for example, one day’s move of only 3,5 miles. A reasonable timetable was nonetheless maintained. Despite hardships, upon arrival at the objective, the brigade attacked without delay with high combat efficiency. Although the popular picture of Burma warfare is portrayed by steaming jungles, elevations as great as 8000 feet were surmounted. On three successive days of fair weather, water froze in canteens and helmets. These extremes in climate did not result in illness for the troops even though one blanket and poncho per man constituted the entire bedding. Fires were out of the question for wandering groups of Japs were always a threat. Mules survived almost 100% and arrived in excellent condition. As the distance traveled increased, the ratio of soldier march fractures went up. Men who otherwise would have remained effective under a shorter overall distance found their metatarsal arches breaking down and a high percentage of such casualties had to be evacuated.

At times evacuation difficulties were a cause of deep concern to the entire command. Air Liaison could not function. No motor roads were available. Natives had vanished, were unemployable, or were fell untrustworthy for this work. Animals were prime loaded with necessary loads and also unsuitable for evacuation. The line of communications was vulnerable to ambush and blockade by the enemy. It was necessary to withhold a rifle company to escort and carry through evacuees for a period of four days. Evacuation at this time was to Mong Wi where a Liaison plane strip served evacuation to the rear. Hemmed in as this strip was by rough mountains, the burden of evacuation was heavy. On several occasions, evacuation parties were able to come within one mile of this strip and were unable to reach it before nightfall. It is considered a benevolent stroke of good fortune that evacuees were brought in without exception. When ordered out for a conference, the CG 5332 Brigade (Prov) covered in a forced mule back ride of one day, the distance traveled by the foot elements in three days of marching. Traveling mounted with a single companion reduced the number of obstacles that confronted mass movement.

Although one blanket and poncho provided the only protection against bitterly cold nights, substantial weight was thereby added to the individual pack. No instances of pack paralysis occurred. However, the weight of the pack is considered a contributing factor to march fractures. To accomplish long range penetration, it was necessary for each man to carry essential items. These were stripped to the minimum by such measures as having each individual carry a spoon and the top of the meat can, in some instances only a spoon and canteen cup. Two canteens were necessary for all water had to be boiled or treated before consumption. Rations, jungle kit, machete, jungle knife, individual weapons, and ammunition had to be man carried as well as shoes, clothing and toilet articles. Compasses were carried by all. Mule loads, such as guns and signal equipment sometimes amounted to 350 pounds. Green fatigues and combat boots, or GI shoes with leggings proved satisfactory as a jungle uniform. Jungle boots were generally used for relief. Helmets were worn except in certain night patrolling. Throughout the movements, airdrop was the only source of rations and other resupply. No more than three days’ rations could be carried. The country seldom offered fair airdrop sites, and frequently a high percentage of the drops was impossible to recover in precipitous wooded areas.

To accomplish the Brigade mission of cutting the Burma Road at Namhpakka, it was necessary to seize extensive battalion objectives. The controlling features were independent broad hills and high ranges. To leave one unoccupied was to leave the enemy in a commanding position. The Loi Kang Ridge, for example, extended approximately two miles in length, rising between the long valley on the west and the open stretch of the Burma Road on the east.

No cover or defiles existed on this sector of the Burma Road. The Japs were well entrenched on the Loi Kang Ridge and held two villages (Loi Kang and Man Sak) which nestled high in its wooded recesses. Only surprise and a quickly prosecuted attack by the second battalion upon its reaches could have ousted the enemy. The attack had to be made up of sheer walls and basic tactics of fire and movement wrenched this ground from enemy hands. Gaining the northern crest it was necessary for this battalion to turn south and fight down the axis of the range, yard by yard driving the enemy back until another battalion (1/475-IR) had seized its objectives and organized the ground. This battalion then executed a limited encirclement of the Loi Kang enemy forces. Thereafter, the 2/475-IR was secure upon the ridge, enemy forces having been killed or forced to decamp. A trail along the only passage down this range had 80 individual pillboxes in a 100-yard area that had to be cleaned out. Continuous enemy counter-attacks were pressed. The 1/475 had to be withdrawn immediately after its participation in this attack to protect the hill features it had secured to the west of Loi Kang Ridge.

During this operation, each Battalion Combat Team had its hands full with its respective objective, all being high-ground features commanding the road. Continuously, however, ambushes, combat patrols, roadblocks, automatic weapons fire, mines, and artillery were used on the road by all battalions and squadrons. Even before the heights were fully taken, the enemy situation had become such that in his withdrawal from the north he had to cease all-day movement over the road and soon all-night movement. The equipment and troops he was able to extricate from the north had to go over the network of roads previously constructed well east of the Burma Road and out of range of the Mars firepower. Many of his wounded, and perhaps many of his death were taken southward toward Lashio through the corridors east of the Burma Road. Disregarding enemy numbers not confirmed as killed, a ratio of six and one-half Japs to one American was established. During these operations, the only equipment to fall into enemy hands was one small radio set. It is possible, but not confirmed, that one American prisoner was taken. One 75-MM piece suffered a direct hit and three others were damaged, but replacement parts put these guns in action on a succeeding day. Both airdrop supply of all classes and liaison plane evacuation of the wounded were under enemy fire throughout this campaign. Air currents were treacherous and inadequate liaison strips were all that could be devised. Little malaria existed, except for recurrences of earlier contraction. Precautions against typhus and dysentery; as well as malaria, were constantly impressed, but some inevitably suffered. Only one latent neurosis developed. Mules were controllable in proximity to hostile and friendly fire. Bamboo cutting made nutritious provender when the tactical situation prevented loose grazing.