Document Source: Operation of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regimental Combat Team, in Sicily during the period July 9, 1943, to August 19, 1943. Personal Experience of the Regimental Headquarters Company Commander, Capt Adam A. Komosa.

This archive covers the operations of the 504-PRCT, in which it participated in the first large scale night airborne operation in military history. After the jump, the paratroopers were scattered over an area of sixty miles in the southern portion of the Sicilian Island. After their reorganization, they moved out to their assigned sectors along the south and west coast of the island. In order to orient the reader properly, it will be necessary to go back several months and give a short resume of the events that lead up to this campaign, which was described by Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister of England, as ‘not the beginning of the end, but the end of the beginning’.

This archive covers the operations of the 504-PRCT, in which it participated in the first large scale night airborne operation in military history. After the jump, the paratroopers were scattered over an area of sixty miles in the southern portion of the Sicilian Island. After their reorganization, they moved out to their assigned sectors along the south and west coast of the island. In order to orient the reader properly, it will be necessary to go back several months and give a short resume of the events that lead up to this campaign, which was described by Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister of England, as ‘not the beginning of the end, but the end of the beginning’.

There was much talk about the soft underbelly of Europe, long before the invasion of Sicily was begun. Preparations were made for a tough and bloody course of the war with the realization that, while the Italians were sure to collapse under the blow, the Nazis would fight stubbornly and bitterly. The Italian nation was disgruntled with its own government, shaken by the reverses in Africa unhappy with the swaggering Germans in its midst, Italy was, in short, poised for the knockout. There were other considerations besides the desirability of knocking out the Axis weak sister that prompted the Anglo-American strategy. There was a good chance of trapping a substantial German army in Southern Italy, besides the certainty of tying up many German Divisions, both of which, if accomplished would relieve the pressure on the Soviet Front, and keep many troops from the defense of occupied France. Control of Sicily would mean, also, control of the Mediterranean and insurance of the shortest supply line from Britain and the US to India and China. In broad terms, the attack against Sicily was to be made by two task forces. The American 7-A, the Western Task Force, would land on the southeast coast of the island, while the British 8-A, the Eastern Task Force, would land on the extreme southeast tip and around the eastern side of the island. The American 7-A was commanded by Gen George S. Patton and consisted of six divisions organized into two Corps, one under Gen Omar N. Bradley and the other under Gen Geoffrey Keyes. Certain French Moroccan troops were to be available and held in Africa as a General Reserve.

Once ashore, the US Army’s mission was to secure the left flank of the operation from enemy resistance, while the center and right flanks drove toward the central highlands of Sicily which dominate the valleys and approaches. At this point, the American was to make contact with the British 8-A, which after securing all the eastern coast and ports, was to move inland. The plan was to sever the island from its mainland connections and force it to fall off its own weight. The strongest concentration of defense was known to be centered in the northwest and center of Sicily. The assault was planned according to the cardinal principles of warfare – strike where the enemy least expects it or, Hit ’em where they ain’t.

Oujda – North Africa

The Regiment was camped outside of Oujda, French Morrocco. The campsite chosen was typical of sites for American training camps. On one side of the town, there were the beautiful rolling plains and ankle-high grass which looked like a soft green carpet flowing gently over the hills and blending into the beauties of the mountains on the left and the blue Mediterranean on the right. So the camp was located on the other side of the town in the middle of the worst dust bowl on the continent of Africa. The Camp was located in a desolate, sterile, rocky, dusty, heat-seared valley, which seemed to be a Nowhere Zone in North Africa instead of the censor’s Somewhere in North Africa, found on the letterheads of these troops so recently from the States. In addition to the scheduled jumps in tricky winds, there was the worst epidemic of dysentery ever imagined in a latrine orderly’s nightmare, and jumps scheduled or unscheduled were made all through the day and night. Men on guard wore entrenching tools as standard equipment. Oujda brought the Regiment the first taste of extended field conditions. Troops lived in long straight rows of pup tents, interspaced with slit trenches. They squatted on the ground and ate from mess kits at the field kitchens. They bathed, shaved, and washed in their helmets and learned the meaning of water discipline.

They washed their clothes in wooden tubs or in halves of discarded oil drums. They gave each other haircuts. Despite the climatic conditions, the camp at Oujda was to become the greatest parade ground the Regiment and Division had graced to date. We were to be the proud recipient of virtually every dignitary in Northwestern Africa. The proud 82nd Airborne Division paraded before 15 allied generals in less than a month. The Division colors were dipped for Gen Mark W. Clark (CG 5-A), Gen Carl A. Tooey Spaats (CG AAF NA-TO), Gen George S. Patton (CG 7-A), Gen Omar N. Bradley (CG 82-A/B), Gen Alfred M. Gruenther (CoS 5-A), Gen Dwight D. Eisenhower, and an impressive row of French and Spanish dignitaries, including Gen Luis Orgaz, High Commissioner of Spanish Morrocco, and many others. With all the visits we had been receiving from dignitaries, it was quite obvious that they had big things in store for us. As Gen Eisenhower (SHAEF) told us some sixteen months later, I owe you a lot, but I will owe you much more by VE Day.

They washed their clothes in wooden tubs or in halves of discarded oil drums. They gave each other haircuts. Despite the climatic conditions, the camp at Oujda was to become the greatest parade ground the Regiment and Division had graced to date. We were to be the proud recipient of virtually every dignitary in Northwestern Africa. The proud 82nd Airborne Division paraded before 15 allied generals in less than a month. The Division colors were dipped for Gen Mark W. Clark (CG 5-A), Gen Carl A. Tooey Spaats (CG AAF NA-TO), Gen George S. Patton (CG 7-A), Gen Omar N. Bradley (CG 82-A/B), Gen Alfred M. Gruenther (CoS 5-A), Gen Dwight D. Eisenhower, and an impressive row of French and Spanish dignitaries, including Gen Luis Orgaz, High Commissioner of Spanish Morrocco, and many others. With all the visits we had been receiving from dignitaries, it was quite obvious that they had big things in store for us. As Gen Eisenhower (SHAEF) told us some sixteen months later, I owe you a lot, but I will owe you much more by VE Day.

All told, the 82-A/B was at Oujda for six weeks. The training was essential, but how, when, and where? The soldiers tried to train in the daytime. It was too hot and dirty to do anything. Allied HQs had us slated for a night airborne operation on Sicily. A high parachute operation had never before been attempted by any army, so organization and training for it offered many new problems. The many intangible and indefinable difficulties of fighting at night in hostile territory, when every object appears to be and often is the foe, had to be overcome. Rapid assembly of the troops and reorganization after landing by parachute appeared to be the greatest problem. Training began at night, compass marches by small groups, organizing in the dark, from simulated parachute drops and glider landings, moving across the country at night and organizing positions, digging foxholes, laying wire, and preparing minefields by the light of the moon. Emphasis was placed on training in judo, demolitions, commando fighting, and the use of the knife. All this worked out well but bayonet practice at 0200 was a little too unique to bring enthusiasm. It was too hot to sleep during the daytime and as a result, the troops became exhausted.

All told, the 82-A/B was at Oujda for six weeks. The training was essential, but how, when, and where? The soldiers tried to train in the daytime. It was too hot and dirty to do anything. Allied HQs had us slated for a night airborne operation on Sicily. A high parachute operation had never before been attempted by any army, so organization and training for it offered many new problems. The many intangible and indefinable difficulties of fighting at night in hostile territory, when every object appears to be and often is the foe, had to be overcome. Rapid assembly of the troops and reorganization after landing by parachute appeared to be the greatest problem. Training began at night, compass marches by small groups, organizing in the dark, from simulated parachute drops and glider landings, moving across the country at night and organizing positions, digging foxholes, laying wire, and preparing minefields by the light of the moon. Emphasis was placed on training in judo, demolitions, commando fighting, and the use of the knife. All this worked out well but bayonet practice at 0200 was a little too unique to bring enthusiasm. It was too hot to sleep during the daytime and as a result, the troops became exhausted.

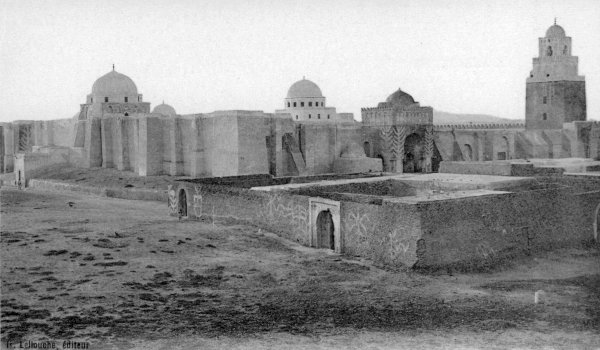

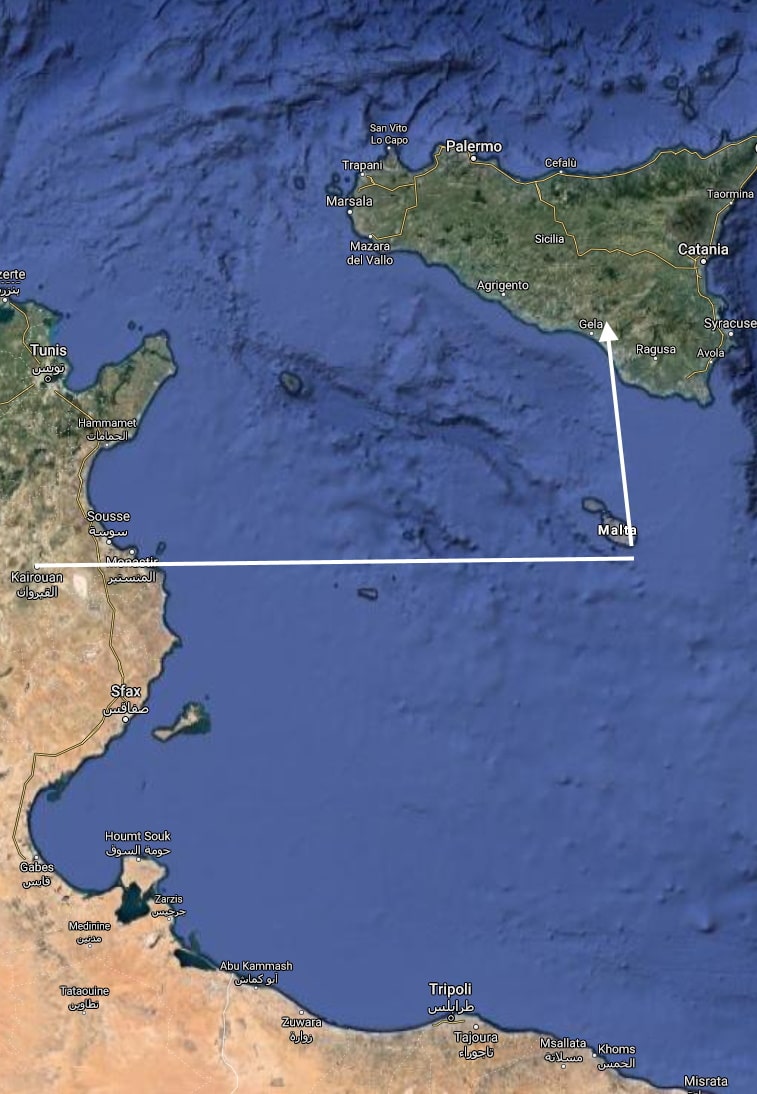

Having completed the ground and refresher training, the Division was now in the process of its next move, closer to combat. On the morning of June 16, 1943, the advance elements departed by truck for the advanced takeoff airfield and dispersal area at Kairouan, Tunisia. The forward bases were dispersed over a wide area in the vicinity of Kairouan, the third holy city in all Islam, according to Uncle Sam’s Guide to North Africa. Holy cities are off-limits of course, not because they are Holy, but because they are too filthy even for healthy soldiers to enter. So, the Regimental Combat Teams were bivouacked in a huge arc around the city in scattered olive groves and cactus patches. As attended, the area was very dusty and the scorching heat unbearable. Within 275 short miles lay the enemy in Sicily nervously waiting for the invasion which certainly would come soon. The troops began to sense the nearness of the battle. Situation huts were set up immediately and conferences were held about the pending attack on the iron-muscled underbelly of Adolf’s Festung Europa. The training was as usual, continuous, with both day and night exercises. Troops got up at 0430 and started at 0600. They got madder and meaner. The Krauts could expect anything.

Emphasis was placed on night assembly in simulated parachute drops. Planes could not be obtained from the Army Air Corps for the purpose of making night parachute jumps. The Combat Team was in an excellent state of training, but there was a serious gap in the combined Ground Forces – Air Corps training. An Air Corps liaison officer was attached to the 82-A/B’s HQs, but he was not used to the best advantage. He did not operate as an integral member of the Division Staff and was not in a position to coordinate plane requirements, etc. An Airborne liaison officer was later attached to the 52nd Troop Carrier Wing. He was made assistant S-3 and proved a real value to the unit in its planning and training. The spirit of cooperation between the 82-A/B and the 52-TCW was excellent; however, the inadequate organization proved the stumbling block. Cooperation alone was not enough for the closely-knit teamwork required. The 52-TCW arrived in the theater qualified for daylight operations and parachute drops over familiar terrain, but unqualified for night operations. At the start of the training program, the wing did night formation and navigation flying with navigational lights. After becoming proficient with navigational lights, the formation flying was done without navigational lights and with resin lights.

Emphasis was placed on night assembly in simulated parachute drops. Planes could not be obtained from the Army Air Corps for the purpose of making night parachute jumps. The Combat Team was in an excellent state of training, but there was a serious gap in the combined Ground Forces – Air Corps training. An Air Corps liaison officer was attached to the 82-A/B’s HQs, but he was not used to the best advantage. He did not operate as an integral member of the Division Staff and was not in a position to coordinate plane requirements, etc. An Airborne liaison officer was later attached to the 52nd Troop Carrier Wing. He was made assistant S-3 and proved a real value to the unit in its planning and training. The spirit of cooperation between the 82-A/B and the 52-TCW was excellent; however, the inadequate organization proved the stumbling block. Cooperation alone was not enough for the closely-knit teamwork required. The 52-TCW arrived in the theater qualified for daylight operations and parachute drops over familiar terrain, but unqualified for night operations. At the start of the training program, the wing did night formation and navigation flying with navigational lights. After becoming proficient with navigational lights, the formation flying was done without navigational lights and with resin lights.

Occasionally, the Air Corps was used to work with Col Edson D.Raff’s 509-PIB’s Scout Company on DZ and resupply exercises. However, the Wing did not fully appreciate the value of these projects and used most of their training time to fly large formations and token drops which had little operational value. Very little real effort was put forth by the 52-TCW to check the location of pin-point DZs at night. Equipment containers were made available in an effort to get the 52-TCW to drop simulated loads on a DZ on practice flights. Very few times were containers used to check the DZ location by the navigator and the jump signal by the pilot. Air photos, for training aids in the location of DZs by night flight, were not used in the majority of training flights. Training of a practical nature was difficult under the existing set-up without a control command over the 52-TCW and the 82-A/B. Despite the necessity of such a step, a full-scale rehearsal of the operation was not conducted. Final training was further hampered because the Wing Air Corps over the final three weeks were engaged in shuttling troops and supplies to advance bases. No exercises involving support aviation, other than a demonstration, were held as were no exercises involving aerial resupply.

On the Fourth of July, the mechanism of final battle preparation swung into full gear with Gen Matthew B. Ridgway, CG of the 82-A/B, and his staff flying to Algiers where they joined the Command Staff of the 1st Armored Corps (reinforced) to complete plans for the invasion of Sicily under Gen Patton, Commander of the highly secret 7-A.

On the Fourth of July, the mechanism of final battle preparation swung into full gear with Gen Matthew B. Ridgway, CG of the 82-A/B, and his staff flying to Algiers where they joined the Command Staff of the 1st Armored Corps (reinforced) to complete plans for the invasion of Sicily under Gen Patton, Commander of the highly secret 7-A.

Every man in the division was filled with speculation on the wheres and whats of the immediate future, but the flies, sand, and sun had done their job in their own insufferable way. With the body hardened and the mind still filled with thoughts of the disagreeable training area, anticipation for the future and combat could not have been keener. Morale was at a peak. The men wanted to tackle anything.

Every man in the division was filled with speculation on the wheres and whats of the immediate future, but the flies, sand, and sun had done their job in their own insufferable way. With the body hardened and the mind still filled with thoughts of the disagreeable training area, anticipation for the future and combat could not have been keener. Morale was at a peak. The men wanted to tackle anything.

The Plan

Information about the enemy indicated that the entire island of Sicily had been prepared for defense. Towns, consisting almost entirely of stone buildings, were reported organized as centers of resistance. All beaches were reported protected by batteries, pillboxes, barbed wire, and mines. Roads were understood to be blocked by AT obstacles. Strength, of the defenders, was stated to be somewhat between 300.000 and 400.000 men.

The plan for the invasion of Sicily provided for landings to be made on the southeastern extremity of the island, with the British and the Canadian forces on the east coast and American forces on the south coast. The American assault forces were to consist of the 3rd Infantry Division, the 1st Infantry Division, and the 45th Infantry Division with attached units,

The plan for the invasion of Sicily provided for landings to be made on the southeastern extremity of the island, with the British and the Canadian forces on the east coast and American forces on the south coast. The American assault forces were to consist of the 3rd Infantry Division, the 1st Infantry Division, and the 45th Infantry Division with attached units,

which were to land in the vicinity of Licata, Gela, and Sampieri, respectively, and parachute troops from the 82-A/B, which were to land inland from Gela. Bradley’s II Corps consisted of the 1-ID and the 45-ID Divisions.

which were to land in the vicinity of Licata, Gela, and Sampieri, respectively, and parachute troops from the 82-A/B, which were to land inland from Gela. Bradley’s II Corps consisted of the 1-ID and the 45-ID Divisions.

After landing, the Paratroopers of the 82-A/B were to be attached to this Corps. The plan of invasion called for one parachute combat team to drop just north of an important road junction about seven miles east of Gela, between known large enemy reserves and the 1-ID’s beaches, with the mission of preventing these reserves from interfering with the amphibious landings. The assaulting paratroopers were the 505-PRCT (Col James M. Gavin), reinforced by the 3/504-PIR (Col Charles W. Kouns).

After landing, the Paratroopers of the 82-A/B were to be attached to this Corps. The plan of invasion called for one parachute combat team to drop just north of an important road junction about seven miles east of Gela, between known large enemy reserves and the 1-ID’s beaches, with the mission of preventing these reserves from interfering with the amphibious landings. The assaulting paratroopers were the 505-PRCT (Col James M. Gavin), reinforced by the 3/504-PIR (Col Charles W. Kouns).