This is not really common for me to use the text of someone else. But sometimes, when a published archive is very interesting and has many photos I have to republish it for my readers. While surfing the Net for wartime photos, I found Harold’s website and started reading the archive on the Canadian Airborne Units. Of course, I am not using the entire archive because the title – Canadian Airborne Units before 1968 – doesn’t really fits with my area of expertise. This is why I asked Harold to use the WW2 part of his work. I hope you will like it because it’s a splendid work and it contains a lot of information. If you want to read the entire archive and many others texts then just [click here] and enjoy the trip.

This is not really common for me to use the text of someone else. But sometimes, when a published archive is very interesting and has many photos I have to republish it for my readers. While surfing the Net for wartime photos, I found Harold’s website and started reading the archive on the Canadian Airborne Units. Of course, I am not using the entire archive because the title – Canadian Airborne Units before 1968 – doesn’t really fits with my area of expertise. This is why I asked Harold to use the WW2 part of his work. I hope you will like it because it’s a splendid work and it contains a lot of information. If you want to read the entire archive and many others texts then just [click here] and enjoy the trip.

1st Canadian Parachute Bn, 1st Special Service Force, Canadian Airborne Units during WW-2.

The Canadian Airborne Regiment traces its origin to the WW2 period, just like the 1.CPB and the 1-SSF which was administratively known as the 2-CPB. The Canadian Airborne Regiment bears battle honors on its Regimental Colors from both units, including the Normandy Landing, the Dives River and the Rhine River Crossings in the case of the former, and Monte Camino, Monte Majo, Monte La Difensa – Monte La Remetanea, Anzio and Rome in the case of the latter.

The 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion was an airborne infantry battalion of the Canadian Army formed in July 1942. After the end of the hostilities in Europe, the battalion was returned to Canada where it was disbanded on Sep 30, 1945. By the end of the war, the battalion had gained a remarkable reputation. They never failed to complete a mission, and they never gave up an objective once taken. They were the only Canadians to participate in the Battle of the Bulge and had advanced deeper than any other Canadian unit into enemy territory. Despite being a Canadian Army formation, it was assigned to the British 3rd Parachute Brigade, a British Army formation, which was itself assigned to the British 6th Airborne Division.

The 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion was an airborne infantry battalion of the Canadian Army formed in July 1942. After the end of the hostilities in Europe, the battalion was returned to Canada where it was disbanded on Sep 30, 1945. By the end of the war, the battalion had gained a remarkable reputation. They never failed to complete a mission, and they never gave up an objective once taken. They were the only Canadians to participate in the Battle of the Bulge and had advanced deeper than any other Canadian unit into enemy territory. Despite being a Canadian Army formation, it was assigned to the British 3rd Parachute Brigade, a British Army formation, which was itself assigned to the British 6th Airborne Division.

On Jul 1, 1942, the Department of National Defense authorized the raising of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion. The battalion had an authorized strength of 26 officers and 590 other ranks, formed into a battalion headquarters, three rifle companies and a headquarters company. Later in the year, volunteers were also requested for the recently formed 2nd Canadian Parachute Battalion, which formed the Canadian contingent of the 1st Special Service Force.

headquarters company. Later in the year, volunteers were also requested for the recently formed 2nd Canadian Parachute Battalion, which formed the Canadian contingent of the 1st Special Service Force.

The 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion was Canada’s original airborne unit, formed on July 1, 1942. Volunteers completed jump training in England then underwent four months of training at Fort Benning, Georgia, and the Parachute Training Wing at Shilo, Manitoba. Part airman, part commando, and part engineer, the paras underwent dangerously realistic exercises to learn demolition and fieldcraft in overcoming obstacles such as barbed wire, bridges, and pillboxes. By March, Canada had its elite battalion, which returned to England to join the British 6th Airborne Division as a unit of the Britain’s 3rd Parachute Brigade.

The 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion was Canada’s original airborne unit, formed on July 1, 1942. Volunteers completed jump training in England then underwent four months of training at Fort Benning, Georgia, and the Parachute Training Wing at Shilo, Manitoba. Part airman, part commando, and part engineer, the paras underwent dangerously realistic exercises to learn demolition and fieldcraft in overcoming obstacles such as barbed wire, bridges, and pillboxes. By March, Canada had its elite battalion, which returned to England to join the British 6th Airborne Division as a unit of the Britain’s 3rd Parachute Brigade.

The initial training was carried out at Fort Benning in the USA and at RAF Ringway in the UK. Groups of recruits were dispatched to both countries with the intention of getting the best out of both training systems prior to the development of the Canadian Parachute Training Wing at Camp Shilo, Manitoba. The group that traveled  to Fort Benning in the United States included the unit’s first commanding officer, Maj H.D. Proctor, who was killed in an accident when his parachute rigging lines were severed by the following aircraft. He was replaced by Col G.F.P. Bradbrooke, who led the battalion until the end of operations in Normandy on June 14, 1944.

to Fort Benning in the United States included the unit’s first commanding officer, Maj H.D. Proctor, who was killed in an accident when his parachute rigging lines were severed by the following aircraft. He was replaced by Col G.F.P. Bradbrooke, who led the battalion until the end of operations in Normandy on June 14, 1944.  In Jul 1943, the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion was dispatched to the UK and came under the command of the 3rd Parachute Brigade of the British 6th Airborne Division. The Battalion then spent the next year in training for airborne operations. Major differences between their previous American training and the new regime included jumping with only one parachute, and doing it through a hole in the floor of the aircraft, instead of through the door of a Douglas C-47 Dakota.

In Jul 1943, the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion was dispatched to the UK and came under the command of the 3rd Parachute Brigade of the British 6th Airborne Division. The Battalion then spent the next year in training for airborne operations. Major differences between their previous American training and the new regime included jumping with only one parachute, and doing it through a hole in the floor of the aircraft, instead of through the door of a Douglas C-47 Dakota.

(Below) The Armstrong Whitworth AW.38 Whitley, flown by RCAF aircrew serving with the RAF, used as a tow-plane for gliders and for dropping paratroops. The Whitley was in service with the RAF at the outbreak of the Second World War. It had been developed during the mid-1930s, and formally entered the RAF squadron service in 1937. Following the outbreak of war in Sep 1939, the Whitley participated in the first RAF bombing raid on German  territory and remained an integral part of the early British bomber offensive. By 1943, it was being superseded as a bomber by the larger four-engined heavy bombers such as the

territory and remained an integral part of the early British bomber offensive. By 1943, it was being superseded as a bomber by the larger four-engined heavy bombers such as the  Avro Lancaster. Its front line service included maritime reconnaissance with Coastal Command and second-line roles including glider-tug, trainer, and transport aircraft. None of these airplanes have been preserved.

Avro Lancaster. Its front line service included maritime reconnaissance with Coastal Command and second-line roles including glider-tug, trainer, and transport aircraft. None of these airplanes have been preserved.

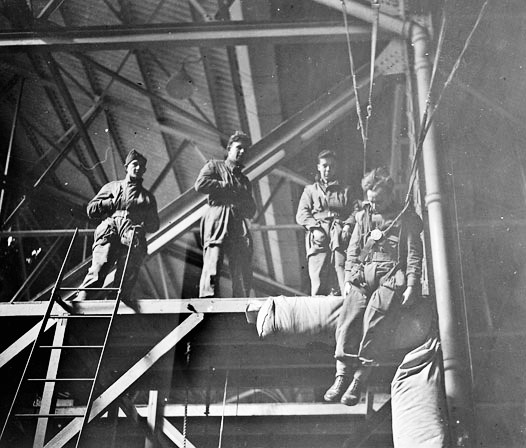

(Right) Paratroopers inside the fuselage of an AW.38 aircraft at the RAF Ringway Paratrooper School, Aug 1942. In 1940, the Whitley had been selected as the standard paratroop transport; in this role, the ventral turret aperture was commonly modified to be used for the egress of paratroopers. Members of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion would have been jumping from these aircraft during their training in the UK at RAF Ringway.

The Battalion served in northwest Europe, including the Landing in Normandy, France, with the 6th Airborne Division, during Operation Tonga, in conjunction with the D-Day landings of Jun 6, 1944. They were part of the 3rd Parachute Brigade which included the 8th and 9th Battalions and the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, and the 7th, 12th, and 13th Battalions of the 5th Parachute Brigade were involved, with considerable casualties.

The Battalion served in northwest Europe, including the Landing in Normandy, France, with the 6th Airborne Division, during Operation Tonga, in conjunction with the D-Day landings of Jun 6, 1944. They were part of the 3rd Parachute Brigade which included the 8th and 9th Battalions and the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, and the 7th, 12th, and 13th Battalions of the 5th Parachute Brigade were involved, with considerable casualties.

On the evening of Jun 5, 1944, the battalion was transported to France in fifty aircraft. Each man carried a knife, toggle rope, escape kit with French currency, and two 24-hour ration packs in addition to their normal equipment, in all totaling 70 pounds.

The battalion landed one hour in advance of the rest of the brigade in order to secure the Drop Zone (DZ). Thereafter they were ordered to destroy road bridges over the Dives rivers and its tributaries at Varaville, then neutralize strong points at the crossroads.

In addition, the Canadians were to protect the left (southern) flank of the 9th Battalion, Parachute Regiment during that unit’s attack on the Merville Battery, afterward seizing a position astride the Le Mesnil crossroads, a vital position at the center of the ridge. Col Bradbrooke issued the following orders to his company commanders, Charlie Co (Maj H.M. MacLeod) was to secure the DZ, destroy the  enemy headquarters (HQs), secure the Southeast corner of the DZ, destroy the radio station at Varaville, and blow the bridge over the Divette stream in Varaville. Charlie Co would then join the battalion at Le Mesnil crossroads.

enemy headquarters (HQs), secure the Southeast corner of the DZ, destroy the radio station at Varaville, and blow the bridge over the Divette stream in Varaville. Charlie Co would then join the battalion at Le Mesnil crossroads.

Able Co (Maj D. Wilkins) would protect the left flank of 9th Battalion during their attack on the Merville Battery and then cover 9th Battalion’s advance to the Le Plein feature. They would seize and hold the Le Mesnil crossroads.

Baker Co (Maj C. Fuller) was to destroy the bridge over the Dives river within two hours of landing and deny the area to the enemy until ordered to withdraw to Le Mesnil crossroads.

The Battalion landed between 0100 and 0130 hours on Jun 6, 1944, in Normandy, becoming the first Canadian unit on the ground in France. For different reasons, including adverse weather conditions and poor visibility, the soldiers were scattered, at times quite far from the planned drop zone.

The Battalion landed between 0100 and 0130 hours on Jun 6, 1944, in Normandy, becoming the first Canadian unit on the ground in France. For different reasons, including adverse weather conditions and poor visibility, the soldiers were scattered, at times quite far from the planned drop zone.

By mid-day, and in spite of German resistance, the men of the battalion had achieved all their objectives; the bridges on the Dives and Divette in Varaville and Robehomme were cut, the left flank of the 9th Parachute Battalion at Merville was secure, and the crossroads at Le Mesnil was taken. In the following days, the Canadians were later involved in ground operations to strengthen the bridgehead and support the advance of Allied troops towards the Seine River.

On Aug 23, 1944, Col Bradbrooke was appointed to the General Staff at Canadian Military Headquarters in London with Maj G.F. Eadie taking temporary control of the battalion. Three days later, on Aug 26, the 6th Airborne Division was pulled from the line in Normandy. 27 officers and 516 men from the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion took part in the Battle of Normandy and the unit suffered 367 casualties.

Of those casualties, 5 officers and 76 men were killed or died of wounds. The unit had to be re-organized and retrained in order to regain its strength and combat-readiness. The Battle of Normandy had brought a major change to the way the war was fought. Airborne troops needed new training to prepare for an offensive role, including street fighting and capturing enemy positions. On Sep 6, the Battalion left Normandy and returned to the Bulford training camp in the United Kingdom. While there, Col Jeff Nicklin became the battalion commander.

In December 1944, the Battalion was again sent to mainland Europe. On Christmas Day they sailed for Belgium, to counter the German offensive in the Ardennes, in what became known as the Battle of the Bulge. On Jan 2, 1945, the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion was again committed to ground operations on the continent, arriving at the front during the last days of the Battle of the Bulge. They were positioned to patrol during both day and night and defend against any enemy attempts to infiltrate their area. The Battalion also took part in a general advance, taking them through the towns of Aye, Marche en Famenne, Roy and Bande. The capture of Bande marked the end of the fight for the Bulge and the Battalion’s participation in the operation.

In December 1944, the Battalion was again sent to mainland Europe. On Christmas Day they sailed for Belgium, to counter the German offensive in the Ardennes, in what became known as the Battle of the Bulge. On Jan 2, 1945, the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion was again committed to ground operations on the continent, arriving at the front during the last days of the Battle of the Bulge. They were positioned to patrol during both day and night and defend against any enemy attempts to infiltrate their area. The Battalion also took part in a general advance, taking them through the towns of Aye, Marche en Famenne, Roy and Bande. The capture of Bande marked the end of the fight for the Bulge and the Battalion’s participation in the operation.

The Battalion was next moved into the Netherlands in preparation for the crossing of the River Rhine. They were active in carrying out patrols and raids and to establish bridgeheads where and when suitable. Despite the heavy shelling of the Canadian positions, there were very few casualties considering the length of time they were there and the strength of the enemy positions. During this time, the Battalion maintained an active defense as well as considerable patrol activity until its return to the United Kingdom on Feb 23, 1945.

Following this action, the Battalion took part in a short reinforcement stint in Belgium and the Netherlands. On Mar 7, 1945, the Battalion returned from leave to start training for what would be the last major airborne operation of the war, Operation Varsity, the crossing of the Rhine. The US 17th Airborne and 6th British Airborne divisions were tasked to capture Wesel across the Rhine River, to be completed as a combined paratrooper and glider operation conducted in daylight.

Following this action, the Battalion took part in a short reinforcement stint in Belgium and the Netherlands. On Mar 7, 1945, the Battalion returned from leave to start training for what would be the last major airborne operation of the war, Operation Varsity, the crossing of the Rhine. The US 17th Airborne and 6th British Airborne divisions were tasked to capture Wesel across the Rhine River, to be completed as a combined paratrooper and glider operation conducted in daylight.

The 3rd Parachute Brigade was tasked to clear the DZ and establish a defensive position road at the west end of the drop zone and, to seize the Schnappenburg feature astride the main road running north and south of this feature.

The 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion was ordered to seize and hold the central area on the western edge of the woods, where there was a main road running north from the Wesel to Emmerich, and to a number of houses. It was believed this area was held by German paratroopers. Charlie Co would clear the northern part of the woods near the junction of the roads to Rees and Emmerich. Once this area was secure, Able Co would advance through the position and seize the houses located near the DZ.

Baker Co would clear the South-Western part of the woods and secure the battalion’s flank. Despite some of the paratroopers being dropped  some distance from their landing zone, the Battalion managed to secure its objectives quickly. The battalion lost its commanding officer, Col Jeff Nicklin, who was killed during the initial jump on Mar 24. Following the death of Nicklin, the last unit commander was Col G.F. Eadie until the Battalion’s disbandment.

some distance from their landing zone, the Battalion managed to secure its objectives quickly. The battalion lost its commanding officer, Col Jeff Nicklin, who was killed during the initial jump on Mar 24. Following the death of Nicklin, the last unit commander was Col G.F. Eadie until the Battalion’s disbandment.

The airborne assault over the Rhine River, (Operation Varsity), was the largest single airborne operation in the history of airborne warfare and also involved the US 17-A/B. Five battalions of the British 6-A/B took part. The first unit to land was the brigade which suffered a number of casualties as it engaged the German forces in the Diersfordter Wald, but by 1100, the DZ was almost cleared of German forces. The key town of Schnappenberg was captured by the 9th Battalion in conjunction with the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion. Despite taking casualties, the brigade cleared the area of German forces, and by 1345, the brigade reported it had secured all of its objectives.

The outcome of this operation was the defeat of the I.Fallschirmkorps in a day and a half. In the following 37 days, the Battalion advanced 285 miles (459 km) as part of the British 6-A/B encountering the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp on Apr 15, 1945, and taking the city of Wismar on May 2, 1945, to prevent the Soviets from advancing too far West. It was at Wismar that the battalion met up with the Red Army (the only Canadian army unit to do so during hostilities, other than a Canadian Film and Photo Unit detachment). The armistice was signed on May 8 and the battalion returned to England.

With the Victory in Europe and the Pacific War ending in Aug 1945, the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion sailed for Canada on the Isle de France on May 31 and arrived in Halifax on Jun 21. They were the first unit of the Canadian Army to be repatriated and on Sep 30, the battalion was officially disbanded. The battalion was perpetuated in the infantry commandos of The Canadian Airborne Regiment (1968-1995), whose colors carried the battle honors: Normandy Landing, Dives Crossing, The Rhine, and North-west Europe 1944–1945.

With the Victory in Europe and the Pacific War ending in Aug 1945, the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion sailed for Canada on the Isle de France on May 31 and arrived in Halifax on Jun 21. They were the first unit of the Canadian Army to be repatriated and on Sep 30, the battalion was officially disbanded. The battalion was perpetuated in the infantry commandos of The Canadian Airborne Regiment (1968-1995), whose colors carried the battle honors: Normandy Landing, Dives Crossing, The Rhine, and North-west Europe 1944–1945.

During the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalions jump into Normandy on D Day, two-thirds of its sticks were dropped miles from the DZ. This unit displayed all the major characteristic initiatives and flexibility of airborne troops along with more than its share of bravery right through to the end of the war. On the cessation of the hostilities in Europe, FM Sir Alan Brooke, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, wrote to the Canadian Chief of the General Staff, now Gen JC Murchie, to say, ‘I realize that circumstances have made it inevitable that the Battalion should now cease to form part of the 6-A/B, but I should like to tell you how sorry we are to lose this magnificent battalion, which has taken such a distinguished part in the great battles of the past year. I know how high is the regard and affection of all ranks of the 6-A/B for their Canadian Parachute Battalion’.

Department of National Defence, Ottawa. August 3, 1945.

The Canadian Army

The King has been graciously pleased to approve the award of the Victoria Cross to No. B.39039 Corporal Frederick George Topham, 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion.

On Mar 24, 1945, Cpl Topham, a medical orderly, parachuted with his Battalion on an enemy strongly defended area east of the Rhine River. At about 1100, whilst treating casualties sustained in the drop, a cry for help came from a wounded man in the open. Two medical orderlies from a field ambulance went out to this man in succession but both were killed as they knelt beside the casualty. Without, hesitation and on his own initiative, Cpl Topham went forward through intense fire to replace the orderlies who had been killed before his eyes. As he worked on the wounded man, he was shot through the nose. In spite of severe bleeding and intense pain, he never faltered in his task. Having completed immediate first aid, he carried the wounded man steadily and slowly back through continuous fire to the shelter of a wood. During the next two hours, Cpl Topham refused all offers of medical help for his own wound. He worked most devotedly throughout this period to bring in wounded, showing complete disregard for the heavy and accurate enemy fire. It was only when all casualties had been cleared that he consented to his own wound being treated. His immediate evacuation was ordered, but he interceded so earnestly on his own behalf that he was eventually allowed to return to duty.

On his way back to his company he came across a carrier, which had received a direct hit. Enemy mortar bombs were still dropping around, the carrier itself was burning fiercely and its own mortar ammunition was exploding. An experienced officer on the spot had warned all not to approach the carrier. Corporal Topham, however, immediately went out alone in spite of the blasting ammunition and enemy fire and rescued the three occupants of the carrier. He brought these men back across the open and although one died almost immediately afterward, he arranged for the evacuation of the other two, who undoubtedly owe their lives to him. This NCO showed sustained gallantry of the highest order. For six hours, most of the time in great pain, he performed a series of acts of outstanding bravery and his magnificent and selfless courage inspired all those who witnessed it.

(Photo left) The Airborne units needed a suitable over-snow vehicle. In April 1942, since no suitable vehicle existed, the US government, therefore, asked automobile manufacturers to look into such a design. Studebaker subsequently created the T-15 cargo carrier, which later became the M-29 Weasel. The T-15 snowmobile vehicle was capable of carrying four men and was used by the 1st SSF in the Aleutians. A larger vehicle known as the T-24 (later standardized as the M-29), was used by the Force in Italy, although in limited numbers. In Jan 1944, 12 of the 100 T-24 Weasels the Force had brought to Italy were uncrated for the first time. The Force found it preferred mules in much of the terrain found in Italy, due to the rugged hills they were forced to operate in. A few Weasels were used by the Canadian Army in Europe.

(Photo left) The Airborne units needed a suitable over-snow vehicle. In April 1942, since no suitable vehicle existed, the US government, therefore, asked automobile manufacturers to look into such a design. Studebaker subsequently created the T-15 cargo carrier, which later became the M-29 Weasel. The T-15 snowmobile vehicle was capable of carrying four men and was used by the 1st SSF in the Aleutians. A larger vehicle known as the T-24 (later standardized as the M-29), was used by the Force in Italy, although in limited numbers. In Jan 1944, 12 of the 100 T-24 Weasels the Force had brought to Italy were uncrated for the first time. The Force found it preferred mules in much of the terrain found in Italy, due to the rugged hills they were forced to operate in. A few Weasels were used by the Canadian Army in Europe.

The 2nd Canadian Parachute Battalion background. The initial idea for these Airborne forces was based on a plan submitted by Geoffrey Pike, a British inventor working for the British Combined Operations. Pyke devised a plan for the creation of a small, élite force capable of fighting behind enemy lines in winter conditions. This was to have been a commando unit that could be landed, by sea or air, into occupied Norway, Romania, and/or the Italian Alps on sabotage missions against hydroelectric plants and oil fields. Allied commandos were to be parachuted into the Norwegian mountains to establish a covert base on the Jostedalsbreen, a large glacier plateau in German-occupied Norway, for guerrilla actions against the German army of occupation.

In May 1942, the concept papers for Plough were scrutinized by Col Robert T. Frederick, a young officer in the Operations Division of the US General Staff. Frederick was given the task of creating a fighting unit for Project Plough and was promoted to Colonel to command it.

In May 1942, the concept papers for Plough were scrutinized by Col Robert T. Frederick, a young officer in the Operations Division of the US General Staff. Frederick was given the task of creating a fighting unit for Project Plough and was promoted to Colonel to command it.

In Canada, the Department of Munitions and Supply was asked to develop a snowmobile and did produce an effective vehicle, the Canadian Armored Snowmobile MK-1. The Penguin was originally open-topped with a two-man crew, a driver in front, and commander in the rear. An aluminum cab gave more room and could be heated. With these modifications, the Penguin gave good service in the Army’s post-war Arctic exercises. The photo (left) is of one of 15 Penguin snowmobiles during Operation Muskox which took place on Great Bear Lake in the Northwest Territories in 1946. They traveled in the dead of winter from Churchill, Manitoba up through the Arctic. Three machines were diverted to Cambridge Bay where the RCMP supply vessel St Roch was frozen in for the winter. One of the three Penguins, No. 8, was commanded by Capt Bob Inglis, Canadian Army. They ended up in Edmonton, Alberta. Machine No. 8 survived and was sent to the Bombardier Museum but because they didn’t build it, they scrapped it.

The photo (left) is of one of 15 Penguin snowmobiles during Operation Muskox which took place on Great Bear Lake in the Northwest Territories in 1946. They traveled in the dead of winter from Churchill, Manitoba up through the Arctic. Three machines were diverted to Cambridge Bay where the RCMP supply vessel St Roch was frozen in for the winter. One of the three Penguins, No. 8, was commanded by Capt Bob Inglis, Canadian Army. They ended up in Edmonton, Alberta. Machine No. 8 survived and was sent to the Bombardier Museum but because they didn’t build it, they scrapped it.

In July 1942, the Canadian Minister of National Defence, James Ralston, approved the assignment of 697 officers and enlisted men for Project Plough, under the guise that they were forming Canada’s first airborne unit, the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion. Due to a decision to raise an actual Canadian parachute battalion, the Canadian volunteers for Project Plough were also sometimes known unofficially as the 2nd Canadian Parachute Battalion. The Canadian element did not officially become a unit until April–May 1943, under the designation, 1st Canadian Special Service Battalion. On 1 May 1943, the commander of the Canadian contingent began signing the unit’s war diary as the CO of the 1st Canadian Special Service Battalion.

While its members remained part of the Canadian Army, subject to its code of discipline and paid by the Canadian government, they were to be supplied with uniforms, equipment, food, shelter and travel expenses by the US Army. It was agreed that a Canadian would serve as second in command of the force and that half of the officers and one-third of the enlisted men would be Canadian. Col McQueen, formerly in command of The Calgary Highlanders in the UK, had returned to North America to accept the position of senior Canadian in the Force. He broke his leg in parachute training on Aug 13, 1942, and left the Force shortly afterward, going to Washington DC in a liaison role for the force. He later commanded The Lincoln and Welland Regiment in Normandy. Col Don Williamson of the Dufferin and Haldimand Rifles took over as senior Canadian and executive officer (second-in-command) of the 1st SSF. Approximately half the leadership positions in this force were occupied by Canadians, with about 1/3 of the unit’s personnel drawn from the Canadian Army.

While its members remained part of the Canadian Army, subject to its code of discipline and paid by the Canadian government, they were to be supplied with uniforms, equipment, food, shelter and travel expenses by the US Army. It was agreed that a Canadian would serve as second in command of the force and that half of the officers and one-third of the enlisted men would be Canadian. Col McQueen, formerly in command of The Calgary Highlanders in the UK, had returned to North America to accept the position of senior Canadian in the Force. He broke his leg in parachute training on Aug 13, 1942, and left the Force shortly afterward, going to Washington DC in a liaison role for the force. He later commanded The Lincoln and Welland Regiment in Normandy. Col Don Williamson of the Dufferin and Haldimand Rifles took over as senior Canadian and executive officer (second-in-command) of the 1st SSF. Approximately half the leadership positions in this force were occupied by Canadians, with about 1/3 of the unit’s personnel drawn from the Canadian Army.

The combat force was to be made up of three regiments. Each regiment was led by a lieutenant colonel and 32 officers and boasted a force of 385 men. The regiments were divided into two battalions with three companies in each battalion and three platoons in each company. The platoon was then broken up into two sections. Following initial training period in Montana, the FSSF relocated to Camp Bradford, Virginia, on 15 April 1943, and to Fort Ethan Allen, Vermont, on 23 May 1943.

The combat force was to be made up of three regiments. Each regiment was led by a lieutenant colonel and 32 officers and boasted a force of 385 men. The regiments were divided into two battalions with three companies in each battalion and three platoons in each company. The platoon was then broken up into two sections. Following initial training period in Montana, the FSSF relocated to Camp Bradford, Virginia, on 15 April 1943, and to Fort Ethan Allen, Vermont, on 23 May 1943.

The 1st Special Service Force. Canadian Paratroopers also drew much inspiration from the history of the 1-SSF. The Regiment bears the 1SSF battle honors Monte Camino, Monte Majo, Monte La Difensa – Monte La Remetanea, Anzio and Rome on its Regimental Colors. As well the unconventional nature of the First Special Service Force, similar to the British SAS and the current US Army Special Forces and elsewhere, was not replicated in the more conventional role of the Canadian Airborne Regiment. Nevertheless, its accomplishments served as a model for many members of the new Airborne.

The 1st Special Service Force. Canadian Paratroopers also drew much inspiration from the history of the 1-SSF. The Regiment bears the 1SSF battle honors Monte Camino, Monte Majo, Monte La Difensa – Monte La Remetanea, Anzio and Rome on its Regimental Colors. As well the unconventional nature of the First Special Service Force, similar to the British SAS and the current US Army Special Forces and elsewhere, was not replicated in the more conventional role of the Canadian Airborne Regiment. Nevertheless, its accomplishments served as a model for many members of the new Airborne.

The First Special Service Force was a unique joint formation of Canadian and American troops assigned to perform sabotage operations in Europe in the Second World War. Simply named Special Forces to conceal its commando or ranger purpose, this unit later gained fame as the Devil’s Brigade. The Canadians were designated the 2nd Canadian Parachute Battalion.

Members were handpicked and sent to Fort William Henry Harrison, Helena, Montana, for special training. The Canadians wore American uniforms and equivalent ranks to eliminate any questions of command among the troops. Their work-up took place in three phases, with extensive physical training throughout the program. The first phase included parachute training, small unit tactics, and weapons handling—all officers and ranks were required to master the full range of infantry weapons from pistols and carbines to bazookas and flame throwers. Next came explosives handling and demolition techniques, then a final phase consisted of skiing, rock climbing, adapting to cold weather, and operation of the Weasel combat vehicle. Exercises in amphibious landings and beach assaults were added later.

Members were handpicked and sent to Fort William Henry Harrison, Helena, Montana, for special training. The Canadians wore American uniforms and equivalent ranks to eliminate any questions of command among the troops. Their work-up took place in three phases, with extensive physical training throughout the program. The first phase included parachute training, small unit tactics, and weapons handling—all officers and ranks were required to master the full range of infantry weapons from pistols and carbines to bazookas and flame throwers. Next came explosives handling and demolition techniques, then a final phase consisted of skiing, rock climbing, adapting to cold weather, and operation of the Weasel combat vehicle. Exercises in amphibious landings and beach assaults were added later.

It was decided that the FSSF would be blooded against the Japanese force occupying the Aleutian island of Kiska. The FSSF arrived at the San Francisco Port of Embarkation on Jul 4, 1943, and sailed for the Aleutian Islands on Jul 10, 1943. On Aug 15, 1943, the 1st SSF was part of the invasion force of the island of Kiska, but after discovering the island was recently evacuated by Japanese forces, it re-embarked and left the ship at Camp Stoneman, California. The FSSF returned to Fort Ethan Allen, arriving Sept 9, 1944.

The FSSF was then sent to Italy where it was reassigned to Gen Mark W. Clark’s 5-A, which was fighting its way north through the rugged mountainous terrain of Italy. German forces entrenched in two mountains were inflicting heavy casualties on the 5-A.

The FSSF was then sent to Italy where it was reassigned to Gen Mark W. Clark’s 5-A, which was fighting its way north through the rugged mountainous terrain of Italy. German forces entrenched in two mountains were inflicting heavy casualties on the 5-A.

After a 12-day attack was stopped cold at Monte la Difensa, the Force went in and cleared the veteran German 104.Panzergrenadier-Regiment from the summit, a feat immortalized in the 1968 motion picture The Devil’s Brigade.

The first regiment with 600 men, had scaled a 1,000-foot (300 M) cliff by night to surprise the enemy position. Planned as a three to four-day assault, the battle was won in just two hours. The force remained for three days, packing in supplies for defensive positions and fighting frostbite, then moved on to the second mountain, Monte Majo, which was soon overtaken. In the end, FSSF suffered 511 casualties including 73 dead and 116 exhaustion cases.

The commander, Col Robert Frederick, was wounded twice himself.

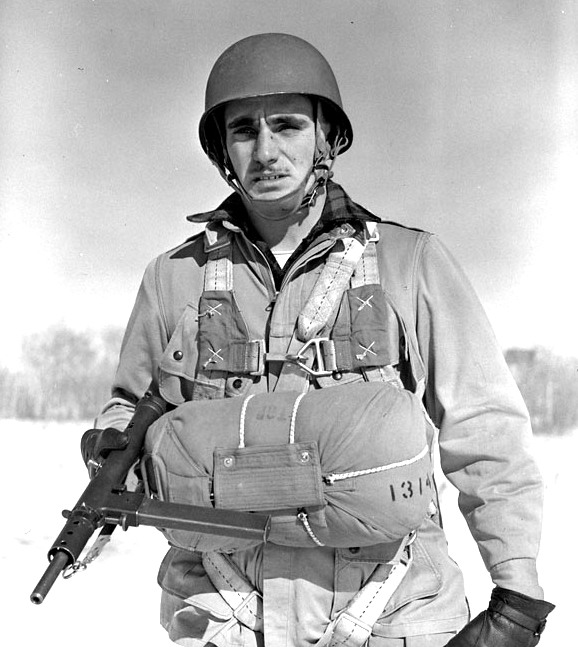

(Photo Above) (1) Lt Tom Brier, 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, wearing American Parachute Jump Suit M-1942, Parachute Pack Assembly T-5, Corcoran Jump Boot, and M-2 Paratrooper Helmet at the A-35 Canadian Parachute Training Centre, Camp Shilo, March 20, 1945. (2) Canadian Paratrooper with a 9-MM Sten gun preparing for a jump at the A35 Canadian Parachute Training Centre, Camp Shilo, 20 Mar 1945. (3) 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion snipers in Ghillie Suits during an inspection by King George VI, Queen Elizabeth and Princess Elizabeth, Salisbury Plain, England, May 17, 1944. (4) Canadian parachute-qualified personnel armed with .303 Lee Enfield rifles, shortly before they were posted to the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion undertaking winter infantry training at A-35 Canadian Parachute Training Centre (Canadian Army Training Centres and Schools), Camp Shilo, Manitoba, Canada, March 20, 1945. (5) Canadian parachute-qualified soldier armed with a portable infantry anti-tank (PIAT) weapon, undertaking winter infantry training at A-35 Canadian Parachute Training Centre (Canadian Army Training Centres and Schools), Camp Shilo, Manitoba, Canada, March 20, 1945. (6) Members of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, Kolkhagen, Germany, April 30 1945.

(Photo Left) FSSF Sergeant, wearing the distinctive FSSF patch on his shoulder, Anzio, Italy, Apr 20, 1944. He is armed with a 2.36-inch Bazooka man-portable recoilless anti-tank rocket launcher, widely fielded by the US Army during WW-2. Also referred to as the Stovepipe, the innovative bazooka was among the first generation of rocket-propelled anti-tank weapons used by infantry in combat. (Photo Right) FSSF. Lt Joe Kostelec, Calgary, Alberta, wearing the distinctive FSSF patch on his shoulder, Nocci, Italy, Jan 1944. Joe Kostelic was a former enlisted man and NCO who had joined the Loyal Edmonton Regiment on Sep 4, 1939. He was wounded in Dec 1943 and received a commission in Jan 1944 after the attack on Mount la Difensa. Joe Springer reported that Lt Kostelec was a natural leader. Kostelic was listed as missing in action (MIA) after a night raid on Anzio.

(Photo Left) FSSF Sergeant, wearing the distinctive FSSF patch on his shoulder, Anzio, Italy, Apr 20, 1944. He is armed with a 2.36-inch Bazooka man-portable recoilless anti-tank rocket launcher, widely fielded by the US Army during WW-2. Also referred to as the Stovepipe, the innovative bazooka was among the first generation of rocket-propelled anti-tank weapons used by infantry in combat. (Photo Right) FSSF. Lt Joe Kostelec, Calgary, Alberta, wearing the distinctive FSSF patch on his shoulder, Nocci, Italy, Jan 1944. Joe Kostelic was a former enlisted man and NCO who had joined the Loyal Edmonton Regiment on Sep 4, 1939. He was wounded in Dec 1943 and received a commission in Jan 1944 after the attack on Mount la Difensa. Joe Springer reported that Lt Kostelec was a natural leader. Kostelic was listed as missing in action (MIA) after a night raid on Anzio.

By Jan 8, after roughly two months in combat, the 1800 men making up the combat strength of the Force had dropped to just over 500. The FSSF received glowing praise from the corps and army commander in the wake of the fighting at Difensa and Remetanea. The FSSF saw continued action throughout the Mediterranean, at Monte Sammucro, Radicosa, and Anzio. For the final advance on Rome, the FSSF was given the honor of being the lead force in the assault and became the first Allied unit to enter the Eternal City. Their success later continued in southern France and then at the France-Italian border. Often misused as line troops, the force suffered continuously high casualties until it was finally withdrawn from combat.

By Jan 8, after roughly two months in combat, the 1800 men making up the combat strength of the Force had dropped to just over 500. The FSSF received glowing praise from the corps and army commander in the wake of the fighting at Difensa and Remetanea. The FSSF saw continued action throughout the Mediterranean, at Monte Sammucro, Radicosa, and Anzio. For the final advance on Rome, the FSSF was given the honor of being the lead force in the assault and became the first Allied unit to enter the Eternal City. Their success later continued in southern France and then at the France-Italian border. Often misused as line troops, the force suffered continuously high casualties until it was finally withdrawn from combat.

In Aug 1944, the Force was able to use its amphibious skills during the landings on islands flanking the invasion beaches in Southern France as part of Operation Dragoon. The unit then fell under the operational control of the 1st Airborne Task Force, clearing the French coastline east to the Italian border.

It was their last major mission, and in Dec 1944, with the need for specialized forces waning, the Force was disbanded. The Canadians went largely to the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, the Americans to the 474th Infantry Regiment (Separate), or to US parachute units. The parachute-trained and combat-tested Canadians of the FSSF were seen as a valuable asset for the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion then training in England.