The Order of Battle for the 81-ID was : Division HQ & HQ Company; 321st Infantry Regiment; 322nd Infantry Regiment; 323rd Infantry Regiment; 306th Engineer Battalion; 306 Medical Battalion, HQ & HQ Battery, 81st Division Artillery; 316th Field Artillery Battalion; 317th Field Artillery Battalion; 318th Field Artillery Battalion; 906th Field Artillery Battalion, HQ Special Troops, 81st Infantry Division; 81st Division Band; 81st Reconnaissance Troop; 81st Quartermaster Company; 81st Ordnance Company, and 81st Signal Company.

The Order of Battle for the 81-ID was : Division HQ & HQ Company; 321st Infantry Regiment; 322nd Infantry Regiment; 323rd Infantry Regiment; 306th Engineer Battalion; 306 Medical Battalion, HQ & HQ Battery, 81st Division Artillery; 316th Field Artillery Battalion; 317th Field Artillery Battalion; 318th Field Artillery Battalion; 906th Field Artillery Battalion, HQ Special Troops, 81st Infantry Division; 81st Division Band; 81st Reconnaissance Troop; 81st Quartermaster Company; 81st Ordnance Company, and 81st Signal Company.

Camp Hyder, Arizona was one of the division-sized cantonments that served the US Army’s Desert Training Center in World War II, and its history is part of the history of the 77th Infantry Division. This Eastern outfit had the dubious honor of including the first foot soldiers sent to the Desert Training Center.

Reborn at Fort Jackson, South Carolina on March 25, 1942, the World War II 77-ID had much in common with the old World War I Division which achieved an outstanding battle record in 68 days of combat ending with the Meuse-Argonne campaign of 1918. A good number of recruits both the old and the new considered the sidewalks of New York home. Consequently, the old 77-ID called itself The Metropolitan Division and proudly wore the gold Statue of Liberty on a blue truncated triangle shoulder patch. The new 77-ID just as appropriately called itself The Liberty Division and wore the same shoulder insignia. Men of the old 77-ID, which included members of the Lost Battalion of the 308th Infantry Regiment, passed the torch to the new generation by bringing the national and regimental colors out of retirement and ceremonially presenting them to the reactivated organizations. Delegations of old-timers visited their successors to give them encouragement and pass along history and tradition.

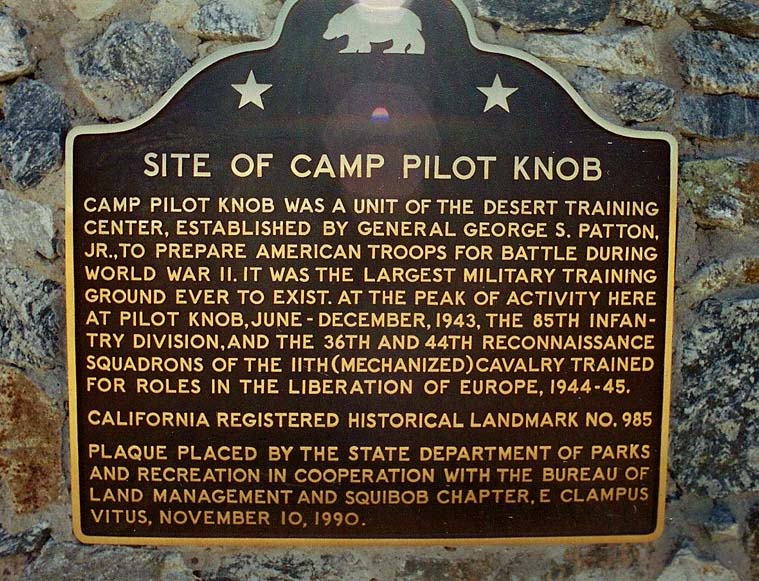

After one year of shedding sweat and fat on the drill fields and training grounds of Fort Jackson, and a shakedown in the Louisiana maneuvers, a self-reliant, cocky, and impatient 77-ID entrained for a water-stop called Hyder on the Southern Pacific Railroad in the heart of the Arizona desert. The troops were convinced that they were a fighting team ready for combat even though the division advance party found itself at Hyder on April Fool’s Day 1943. At that time the Allies had not yet won the North African Campaign, so a need for desert-hardened infantry was anticipated. Consequently, several infantry divisions were scheduled to train in the Desert Training Center, initially established to train the tank, tank destroyer, artillery, and supporting units of Patton’s I Armored Corps.

These infantry divisions assigned to the Arizona desert included the 77-ID at Camp Hyder, the 81-ID at Camp Horn, and the 8-ID at Camp Laguna. At Hyder (elevation 536 feet) the Southern Pacific Railroad passes just north of the Agua Caliente Mountains, their slopes covered with volcanic rock. These mountains bear the name of the hot water springs at their southern end several miles south of the rail line. This oasis served the Spanish explorers as early as 1748, the gold-seeking 49ers on the old trail between Tucson and Yuma Crossing, and health seekers at the time of arrival of the 77-ID. The 77-ID Band welcomed the troop trains with such appropriate tunes as This Is The Army and There’ll Be A Hot Time as one by one they rolled to a stop at the siding. The transition from comfortable Pullman cars, good food, and clean sheets to the barren desert with its powdery ankle-deep dust, piles of folded tents, and two miles of survey stakes was morale busting shock!

As each company detrained, it was marched off through the choking dust to its assigned area where it erected a double row of pyramidal tents. Each tent contained 6 cots, 6 straw ticks, 12 barracks bags, and very quickly a population of lizards, scorpions, and flies. Even today, this experience is not forgotten because the 77ers who retired to Arizona show little interest in revisiting the site of their old tent city. Heavy construction was the forte of the 302nd Engineers. When roads disappeared in the powdery silt, they rebuilt them with rock blasted from the naked Agua Caliente Mountain. Since the nearest water was six miles away at the Agua Caliente Hot Springs, they drilled a very deep well near the railroad and luckily obtained a flow of 120.000 gallons per day. A huge shower facility was built at the well site. However, its value was lessened by the long dirty marches between the tent city and the showers. The training was impeded by the necessary acclimatization and by Mother Nature.

For example, it was necessary to police the firing range each morning to remove the rattlesnakes. Platoon-sized, six-day compass marches were impeded by deep un-mapped arroyos that slowed travel to caches of water and rations. Several narrow escapes from death and frequent instances of real hardship resulted. Also, when the division was called up to maneuver as a whole on a broad front, clouds of rolling dust engulfed the landscape for days as 13.000 men and hundreds of vehicles churned up the dust.

Training included service as guinea pigs to test the drinking water requirements of foot soldiers in the desert. Patton, who established the Desert Training Center rules or training methods, planned to develop lean and hard desert troops by making the training as rigorous and as realistic as possible. Unquestionably, the General was a superb military tactician, but he lacked knowledge of human physiology. All his attempts to forcibly acclimatize soldiers to using only one canteen of water (one quart) per day failed as measured by increasing casualties.

The 77-ID proved the hard way what Sir Hubert Wilkins, an Australian-born polar explorer and desert expert tried to tell Patton. One quart of drinking water per day is far from sufficient to replace body losses in 120°F desert temperatures in the nonexistent shade. The Army’s concern for the physiological aspects of desert training prompted the Quartermaster General to assign a team headed by Wilkins and Conservationist Weldon F. Heald to the grim human proving ground that was the Desert Training Center. Their job was to evaluate the performance of clothing and equipment and to recommend improvements. Also, they unofficially were to seek clues to the multiplying physiological crackups. This team is headquartered at the Blythe Air Base and collaborated with the Army Air Corps Aero Medical Laboratory at Wright Field, Ohio.

It found the most comfortable desert summer clothing to be light khaki trousers and an open-necked, long-sleeved cotton khaki shirt. Shorts and rubber-soled shoes were eliminated early in the test program. Tents with a second canvas roof 12 to 15 inches above the first reduced daytime temperatures about 10°F. Human tests in the 77-ID confirmed that a soldier must replace each 24-hour water loss in order to fight effectively another day. The Wilkins Heald data shows that men on desert maneuvers during the summer months can sweat as much as 2/3 gallons in 24 hours and such accumulating water deficits quickly made for hospital casualties.

We learned that 20 to 25 miles are about the limit for walking in the desert, but whatever the individual limit was, each additional quart of water boosted a man’s capability for walking about 5 miles. Another unique feature of the 77-ID’s desert training program was the Bull Dog School established at a remote site by Lt Col Gordon F. Kimbrill of the British Commandos. Under the most realistic conditions possible, with lavish use of service ammunition, all company officers and many NCO’s of the division practiced small unit tactics, hand-to-hand fighting, infiltration under fire and village fighting. A week at this school sweated many pounds from any man and added much to his skill and self-confidence. He took part in patrols against ‘the enemy’ who fired live ammunition. He manufactured and used demolition charges and booby traps. He fired all infantry weapons under all conditions. He lived hard and dangerously because despite precautions, men were hurt and even one officer was killed.

Discipline was not maintained by means of a conventional stockade. Instead, a Training Company was established in a very isolated location where prison life was even more rigorous than at the Bull Dog School. News of the tragic fate of one attempted AWOL limited the size of this company to only a few. The story of the buzzard-torn remains and the empty canteen in a waterless arroyo spread rapidly and with effect. Life at Camp Hyder included some recreation. A limited amount of beer and soft drinks found their way into the Post Exchanges even though the ice supply to cool them was inadequate. Nightly movies and a few courageous Hollywood troupes did much to minimize the boredom. Baseball, boxing, and other athletic activities permitted representatives of the various units to compete. The Engineers even found time to rebuild the swimming pool at Agua Caliente where the water was abundant though hot. Best of all were visits to Phoenix. This city, 100 miles to the east, was a recreation spot for the dehydrated soldiers, and its hospitality was appreciated. In its modern hotels and homes, they scrubbed off desert dust and drank cool liquids, and here in the city, the wives of the 77-ID found houses and apartments.

While selected personnel and units took their turn in participating in desert compass marches, serving as human guinea pigs, or in enduring life at the Bull Dog School, the bulk of the division concentrated on a more conventional training program involving: week 1 – individual, crew, and squad training; week 2 – company or battery training; week 3 – battalion training; week 4 – combat team training; weeks 5 to 7 – division field exercises, and weeks 8 to 13 – corps maneuvers. This regime was supplemented by instructions from HQ Army Ground Forces that the training in the DTC was to emphasize:

(1) operations with restricted water supply;

(2) sustained operations remote from a railhead;

(3) dispersal of combat groups, during which constant threat of hostile air and a mechanized attack would be simulated;

(4) speed in combat supply, particularly of ammunition and refueling;

(5) supply under cover of darkness;

(6) desert navigation for all personnel;

(7) laying and removal of minefields by all personnel;

(8) maintenance and evacuation of motor vehicles;

(9) special features of hygiene, sanitation, and first aid;

(10) combined training with the Army Air Forces.

By late June 1943, the 77-ID moved by motor convoy to Palo Verde in the California desert for the IX Corps maneuvers. There they joined their Blue teammate of the 7th Armored Division, and attacked ‘the enemy’, the 8th Motorized Division, after an 80-mile advance in a single night to surprise him in Palen Pass. The 77-ID performed well as a division in this mock war of movement. However, the Division’s leadership, physical and disciplinary standards were considered unsatisfactory by Gen McNair, Ground Forces Commander who directed the 77-ID to return to Camp Hyder and correct its deficiencies. Thus, late in July 1943, the 77-ID again occupied their old tent rows. This decision was a bitter disappointment to a fighting team convinced it was ready for combat before coming to Camp Hyder in the first place, so morale noticeably dropped. Fortunately their commander, Maj Gen Andrew D. Bruce established the 77-ID’s desired effectiveness within two months after rather drastic attention from officers. Bruce sharpened the 77-ID via strenuous six-day marches in the mountains and desert east of Hyder. This included night marches along narrow mountain roads, camouflage instruction, patrol missions over difficult terrain, and close-air-support coordination.

McNair again inspected the division and observed some of these field exercises. He seemed favorably impressed, because, on September 15, 1943, the 77-ID was ordered to entrain for Indian Gap Military Reservation in Pennsylvania. Nature celebrated the 77-ID’s departure with a great natural phenomenon. It rained. Not once but several times. An awesome wind and dust storm always preceded the rains and ripped and flattened whole rows of tents. Not once but several times on successive nights. And flash floods washed away parts of the camp as if to say Farewell, 77-ID! Finally, following the Army logic, and after five or six months at the Desert Training Center, the 77-ID was sent to the Pacific jungles to fight the Japanese. The Division landed on Guam on July 21, 1944, in Leyte in the Philippines on November 23, in Okinawa on March 26, 1945, and in Shima on April 16 where Ernie Pyle was killed.