Large quantities of destroyed artillery and tank destroyers – lightly armored half-tracks mounting a low-velocity 75-MM AT cannon – would be visible; in some cases, the American artillerymen fled so precipitously that they did not even pull the firing pins, and German engineers would have blown up the pieces rather than lumber themselves with incompatible calibers. The infantry had been issued bazookas for their AT defenses but had not been trained in their use. Still, bazookas would show up in the archaeology, creating an overall picture of a well-armed US force inexplicably overwhelmed by the attack.

The archaeology would show the location of the detachments, what type of troops they were, and indications of the detachments’ sizes. A superficial conclusion would suggest that the Americans were taken completely by surprise by a huge force moving with lightning speed; however, this is not what happened – Rommel’s advance was forceful but methodical, though whether this could be shown from the archaeology is more doubtful. But in any event, a tactical survey of the approaches to the pass would show that there was no room for such a putative huge attacking force, nor did the terrain allow for a stealth attack, at least not against a reasonably attentive enemy. A drop of Fallschirmjäger might have explained the surprise, but paratroopers have distinctive gear, and none was found.

An observer intimately familiar with World War II US Army tactics might be able to see from the information gleaned that the troops were too spread out for doctrine, but it would take a highly attuned observer to recognize this. Similarly, the archaeology would show no or only rudimentary entrenchments, when good military practice would have led one to expect elaborate defenses – but again, it would take an expert to ‘see’ the absence of a feature. To further complicate the picture, the archaeology would not turn up any German or Italian armor destroyed by bazookas.

FREDENDALL’S FOLLY

Fredendall’s command post complex would certainly be found by our putative future archaeologist. Assuming that our hypothetical colleagues would have worked through the ‘it no doubt served ritual purposes’ stage and established, maybe by identifying traces of the telephone cables radiating from the bunker, that the facility was a command post – what then? Our archaeologist would have a reasonably good understanding of the army regulations of the first half of the 20th century, and a good knowledge of the reasonably contemporary comparators – such as the ad hoc trench systems of World War I, or the permanent installations of the Maginot Line. Fredendall’s CP is neither; it is too far away from the front, too elaborate, to fit into the model of a WW I ad hoc field fortification; and it is too improvised and insufficiently tied into enemy-facing bunker systems to fit the Maginot Line pattern.

Depending on the foreshortening of perspective that results from distance in time to the events observed, our archaeologist might rationalize that both the WW I trench systems and the Maginot Line were created within the same generation, and in the same geographic area – the geographic and temporal accumulation of the witnesses could well argue that it is they that are the oddity, their prevalence being a mere artifact of as yet imperfectly understood special circumstances, while Fredendall’s folly was, in reality, a singularly fortuitous window to a generally applicable rule. If our archaeologist had persuaded him – or herself of this consideration, the next move would be a futile quest to find the Fredendall-style CP on other known battlefields from the era.

THE SCAVENGED BATTLEFIELD

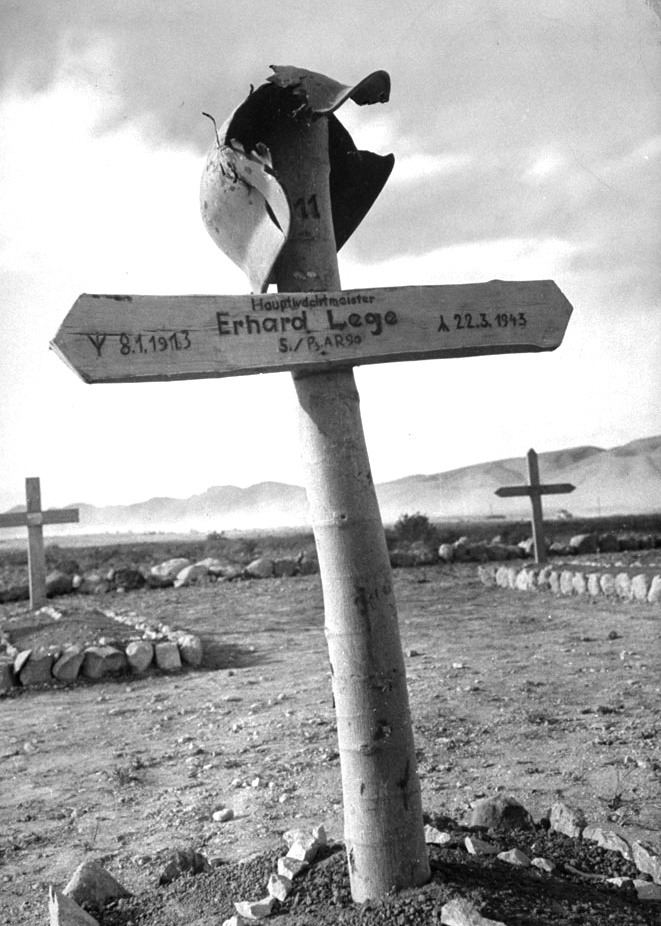

One constraint on battlefield archaeology, and relating to the attentiveness to what might be missing, is this: Which debris from the battle might have been removed after the battle, whether out of piety, such as the burial of the dead; or because the equipment was still in reasonably good condition and was re-usable; or Battle of the Kasserine Pass scavenged because the raw material was intrinsically valuable and as such recyclable; or which would have been obliterated by the forces of nature, from the natural decay of flesh, leather, and textiles, to the action of natural scavengers from corvids and vultures to wolves and rats?

Experience from Afghanistan (historically and in the current wars) shows that in a society where extractive resources are unavailable (or the constraints on their valorization are high), the incentive to recycle is so great that e.g. the carcasses of armored vehicles are typically stripped down to leave only the frame behind – a hulk too heavy to move and too hard to cut without specialized equipment.

The medieval battlefield was usually picked over meticulously for anything worth keeping; WW I battlefields offer more rewarding archaeology since the heavy artillery could bury whole units, and the metal rifles, bayonets, belt buckles, helmets, and epaulets provide a wealth of information. Spent medieval arrows were typically recovered and re-used, since an arrow was an expensive, technologically sophisticated piece of equipment, but on the Towton Battlefield, the mass grave was only discovered because so many arrowheads had lodged in the corpses that their metal signature was recorded half a millennium later, and even though the fallen had been stripped of any valuable metal before burial.

5. SOURCES

AXIS MORAL SUPERIORITY

A comparison between the contemporaneous ‘official’ reporting sheds little light on the matter – US newsreels gloss over the battle. In fairness, in the larger scheme of things, it was a minor setback, it was not so obviously disastrous that there would have been a need to provide elaborate explanations. The Nazi press would certainly have extolled the brilliant feat of arms made possible by the Führer’s superior men, morale, and technology, but the battle’s propaganda value was reduced by the Wehrmacht’s inability to exploit its success due to a dearth of supplies, and the victories of Prussian aristocrats like von Arnim tended to be downplayed in favor of generals from middle-class backgrounds like Rommel and Kesselring, both the sons of schoolmasters. In fact, the Wochenschau for the week praises the performance of the Führer’s troops and includes a brief shot of Rommel, but does not harp on the commanders.

The German-Italian commanders and staff officers on the ground must have had an inkling that the US dispositions were not those of an experienced commandant, but then already at Faïd Pass and Sidi Bou Zid earlier, the Axis had taken advantage of the Americans’ inexperience, so the Allied failure may have appeared only as a matter of degree, and not in the sharp relief raised by the American army records. Interrogation of Prisoners of War might have yielded more information, but as the Axis eventually lost, any such conclusions, if they were drawn, have vanished into the archives or altogether.

FIGHTING YESTERDAY’S WAR

While the German attack was no doubt well-timed and executed with Rommel’s usual skill, the magnitude of its success in terms of US v. German tank losses, men captured and materiel destroyed was entirely due to US failings, and not to German-Italian superiority in numbers, quality of equipment, or morale. Inadequate tactics did play a part. Especially the battles around Sidi Bou Zid, that preceded the Kasserine Pass, revealed that the US Army’s doctrine was not fit for purpose, and had not fully developed armor-centered combined arms tactics. This would be rethought, but a full absorption of the principles of combined arms use would take time, and the US Army won victories even before the new principles were fully developed. Also, Sidi Bou Zid was a US attack that was annihilated by the German defenders; at the Kasserine Pass, the US side was on the defensive, and while there too tactical lessons were learned, especially for the operational doctrine of the tank destroyers, II Corps’ main problem was not inappropriate or inadequate doctrine. In this, the Kasserine Pass was very different from e.g. the French collapse in 1939, where outmoded tactics and ossified command structures paralyzed the French Army to such an extent that it was unable to bring its strength to bear or to exploit dangerously exposed German vulnerabilities.

This catastrophe led to considerable soul-searching and fundamental change in tactics, (Cohen/Gooch, Military Misfortunes) and discredited the French army command to such a degree that a fairly low-ranking officer like Charles De Gaulle could claim French leadership. The battle did not lead to a reorganization of the US order of battle or restructuring of lines of command. Such fundamental rethinking and soul-searching are visible in the medieval record in the wake of stinging defeats, with e.g. the burgeoning of military and chivalric literature in France during the 14th century being attributed to a desire to find reasons for France’s dismal showing in the Hundred Years’ War, and institute reforms to turn the situation around. No such preoccupation is seen in English literature – success does not engender reflection. (Taylor, English Writings, pp. 74-75)

HOME ADVANTAGE

From the sources and the background information, it would have been clear that neither side was fighting on its home ground, so neither side had an advantage of familiarity with the terrain, or acclimatization to the environment, or adaptation of terrain – or climate-specific tactics.

TREACHERY BY THE POSTERN GATE

Battles are frequently won or lost by guile or treachery – could some Tunisian shepherd have shown Rommel a secret path to take him behind the American lines? Such a scenario might help to support the ‘surprise’ story, but the battlefield was too spread out for a single such event to make a difference. The archaeology shows that the US infantry occupying the pass were attacked not by infantry streaming over the heights from behind, as they would have been if it had been an infiltration story, but by the textbook German combined-arms force of armor and mechanized infantry, supported by artillery and ground-support airplanes; it is extremely difficult to sneak tanks anywhere, even more so over mountains. Furthermore, where a victory was based on such a device, the sources delight in saying so.