Source Document: Parker and the Team, 1945; 424th Infantry Regiment, 106th Infantry Division, 82nd Airborne Division, EUCMH archives, AAR, Parker’s Crossroads, Baraque de Fraiture, Battle of the Bulge, Belgium, 1944

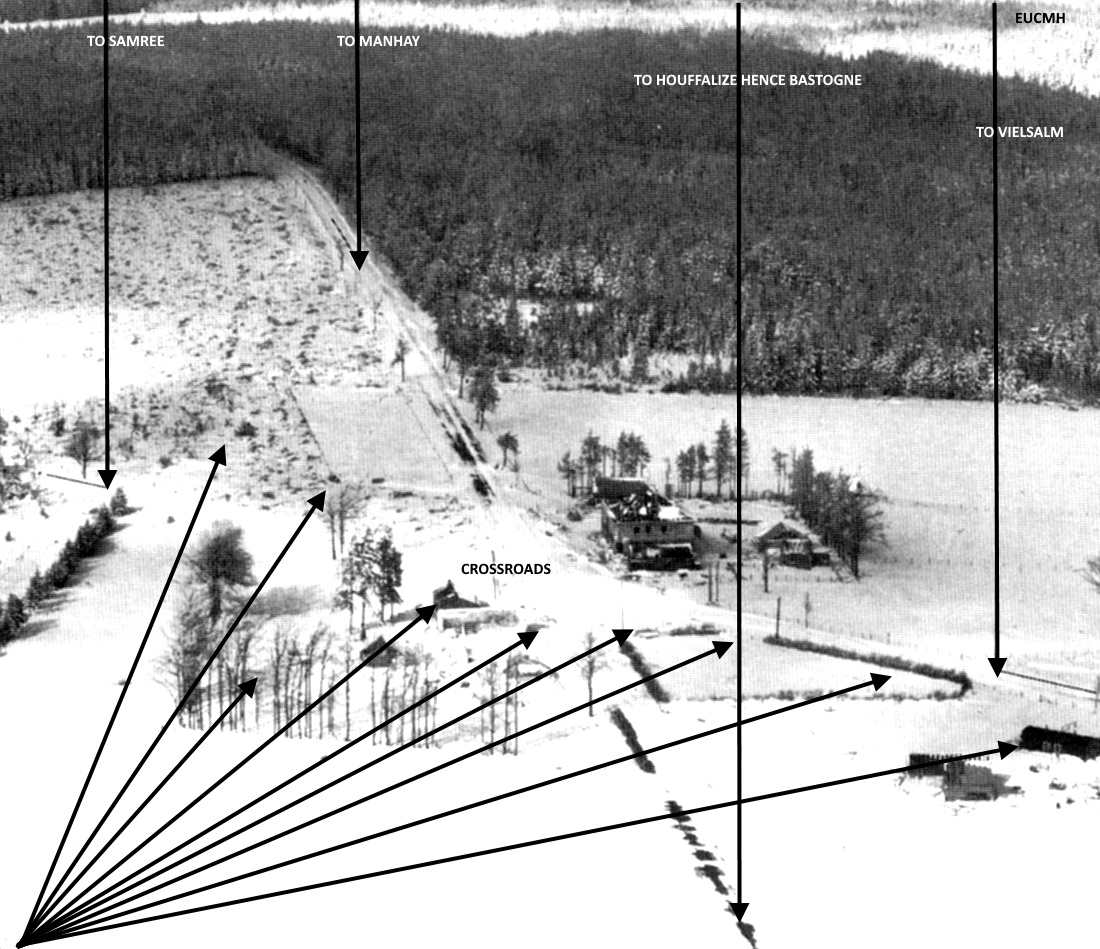

The tactical situation may require a rigid defense of a fixed position. Such a defense, if voluntarily adopted, requires the highest degree of tactical skill and leadership. In the forested hills of eastern Belgium, stands the tiny hamlet of Baraque de Fraiture at the intersection of two good highways, west-east, La Roche en Ardennes – Vielsalm and south-north, Bastogne – Houffalize – Liège. To see this little clutch of buildings, one would hardly think that the red tide of war had ever washed over them.

The tactical situation may require a rigid defense of a fixed position. Such a defense, if voluntarily adopted, requires the highest degree of tactical skill and leadership. In the forested hills of eastern Belgium, stands the tiny hamlet of Baraque de Fraiture at the intersection of two good highways, west-east, La Roche en Ardennes – Vielsalm and south-north, Bastogne – Houffalize – Liège. To see this little clutch of buildings, one would hardly think that the red tide of war had ever washed over them.

Yet, this now-peaceful crossroads was the scene of fierce combat, one of the most heroic that ever graced the annals of American arms. For in the winter of 1944, a skeleton headquarters and a bob-tailed, three-gun battery of light howitzers, the forlorn remnant of a once potent 589th Field Artillery Battalion of the 106th Infantry Division, chugged wearily up to the junction under the command of Maj Arthur C. Parker. The battalion’s mission was to organize and defend the crossroads when a great wave of Nazi armor and infantry had cracked the Allied front, reaching northwestward toward the crossings of the Meuse River and the vital Port of Antwerp. A dangerous split between the British and American armies was a real possibility.

Yet, this now-peaceful crossroads was the scene of fierce combat, one of the most heroic that ever graced the annals of American arms. For in the winter of 1944, a skeleton headquarters and a bob-tailed, three-gun battery of light howitzers, the forlorn remnant of a once potent 589th Field Artillery Battalion of the 106th Infantry Division, chugged wearily up to the junction under the command of Maj Arthur C. Parker. The battalion’s mission was to organize and defend the crossroads when a great wave of Nazi armor and infantry had cracked the Allied front, reaching northwestward toward the crossings of the Meuse River and the vital Port of Antwerp. A dangerous split between the British and American armies was a real possibility.

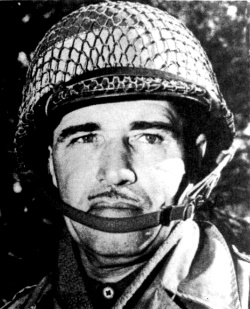

1/Sgt Richard Raymond

For three 105-MM howitzers to hold the outpost line is not a conventional assignment for a divisional battery and deserves an explanation. They represented all that was left of a 12-gun battalion in direct support of the 424th Infantry Regiment, a regiment of the 106th Infantry Division (Golden Lions). Their misfortune was to have been at the point of a great enemy offensive just one week after arriving from training camps in England.

The Golden Lions had moved directly into the foxholes and trenches vacated by the veteran 2-ID. Man for Man and Gun for Gun, as the orders put it. The relief went smoothly enough, but the division commander, Gen Alan W. Jones, was concerned about the exposed positions of his regiments and the extreme length of the line they were to occupy nearly 22 miles. Higher Hqs had called it a Ghost Front with little or no enemy activity, but Jones and his staff at once set about making the lines more secure. He had hoped to have a period of gradual workouts against the formidable West Wall (Siegfried Line) before serious operations began in the spring. But on December 16, Hitler’s tanks rolled, and the Battle of the Bulge was on. In a three-day nightmare, Gen Jones’ green division including his own son Lt Alan Jones (HQs 1/423-IR), swamped and broken by powerful armor and infantry thrusts lost two of his three-line regiments which were surrounded and forced to surrender. The remainder felt lucky to be able to pull back to more defensible positions around St Vith.

The Golden Lions had moved directly into the foxholes and trenches vacated by the veteran 2-ID. Man for Man and Gun for Gun, as the orders put it. The relief went smoothly enough, but the division commander, Gen Alan W. Jones, was concerned about the exposed positions of his regiments and the extreme length of the line they were to occupy nearly 22 miles. Higher Hqs had called it a Ghost Front with little or no enemy activity, but Jones and his staff at once set about making the lines more secure. He had hoped to have a period of gradual workouts against the formidable West Wall (Siegfried Line) before serious operations began in the spring. But on December 16, Hitler’s tanks rolled, and the Battle of the Bulge was on. In a three-day nightmare, Gen Jones’ green division including his own son Lt Alan Jones (HQs 1/423-IR), swamped and broken by powerful armor and infantry thrusts lost two of his three-line regiments which were surrounded and forced to surrender. The remainder felt lucky to be able to pull back to more defensible positions around St Vith.

During the withdrawal, the 589th Field Artillery Battalion (106-ID) was ambushed and cut off and most of the battalion including its commander who was captured. Only a handful from Hqs Battery and the first three howitzers of Battery A escaped. These were the guns that Maj Parker, formerly battalion S-3 but then acting commander, had into position around the crossroads at Baraque de Fraiture. But he meant to make a fight of it. Parker had elected to conduct an Alamo Defense using his combat group made of a few men of the Troop D of the 87th Cavalry Recon Squadron (7-AD), a small outfit of Battery D the 203-AAA-AW Battalion (7-AD), a couple of M-4 Medium Shermans of the 3rd Armored Division, a small outfit of the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion and finally, Fox Co of the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, from the 82nd Airborne Division.

During the withdrawal, the 589th Field Artillery Battalion (106-ID) was ambushed and cut off and most of the battalion including its commander who was captured. Only a handful from Hqs Battery and the first three howitzers of Battery A escaped. These were the guns that Maj Parker, formerly battalion S-3 but then acting commander, had into position around the crossroads at Baraque de Fraiture. But he meant to make a fight of it. Parker had elected to conduct an Alamo Defense using his combat group made of a few men of the Troop D of the 87th Cavalry Recon Squadron (7-AD), a small outfit of Battery D the 203-AAA-AW Battalion (7-AD), a couple of M-4 Medium Shermans of the 3rd Armored Division, a small outfit of the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion and finally, Fox Co of the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, from the 82nd Airborne Division.

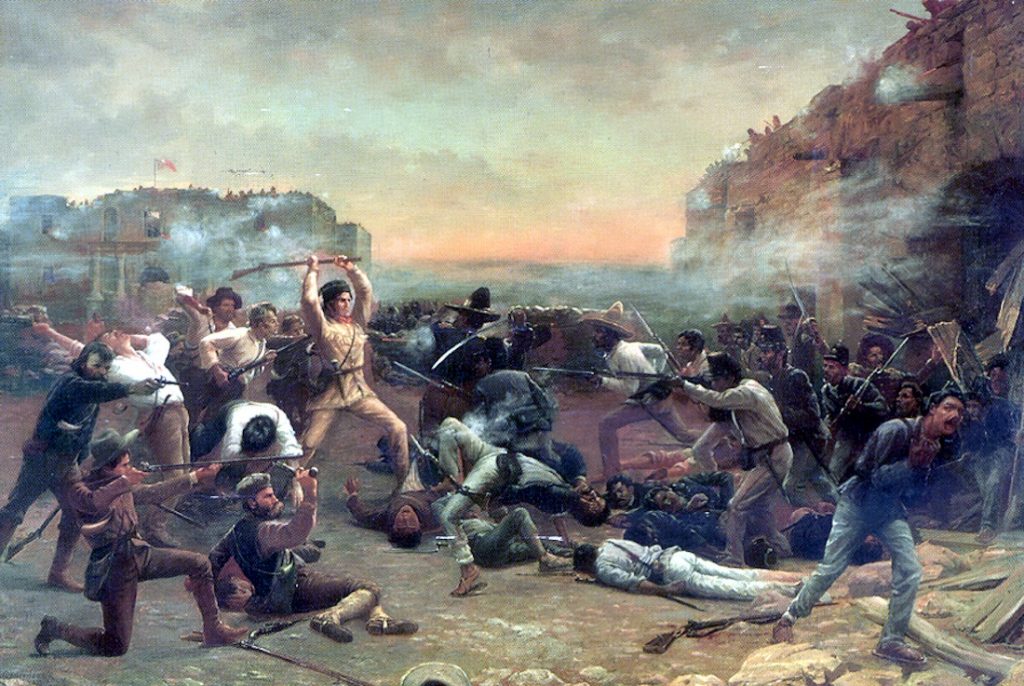

The planned Alamo Defense deserves a serious study as an option for the commander of a force facing a greatly superior enemy, given a vital defensive mission and meager resources to sustain it. Though the historical precedent is obvious, this tactic is defined here as the rigid defense of a key position carried out to the utter destruction of the command with the objective of forcing the enemy to expend significant amounts of men, material, and especially time, thereby enabling other friendly forces to regroup and fight elsewhere to better advantage.

An Alamo Defense is an act of gritty self-sacrifice. This defense requires the utmost leadership and tactical skills. It also demands rare moral courage and dazzling salesmanship to persuade other units and individuals to stay and join an underdog team, qualities Maj Parker had in abundance. The classic example of the Alamo Defense was the heroic stand in 480 BC of Leonidas and his 300 Spartans against the Persian hosts. In truth, the fight at the Alamo might, with perfect justice, be called Thermopylae Defense, but here it seems more appropriate to relate to American military tradition. There are four critical elements in the Alamo Defense. First, the chosen terrain is one on which the enemy can’t readily bypass or push through the defending force. Second, this type of defense is assumed voluntarily when less drastic courses of action are available. Next, combat is maintained to the bitter end, with no breakout or fighting withdrawal, except, perhaps, for a few who escape during the final collapse.

Last, the correctness to make the decision to make the Alamo Defense is confirmed by the outcome, other friendly forces used the time well and fought on to victory. For only the mystic, sublime faith in the rightness of their cause and the hope that their deaths will not go unavenged can infuse most rational soldiers with the spirit to carry such a black business to its conclusion.

At Thermopylae, the Spartans held a narrow cliff-side road and were immovable by the huge masses of Persians. Only when a Greek traitor informed King Darius of the existence of a goat path around the little army did a flanking column succeed in getting behind them. Perfectly sure of their fate, Leonidas and his men permitted their allies to withdraw and then fought to the last man. In contrast to the rough terrain at Thermopylae, the Texans’ little fortress at the Alamo represented a psychological roadblock. Santa Anna, who boasted of being the Napoleon of the west, could not, for his very pride’s sake, simply march around San Antonio and press on toward his true objective, Sam Houston’s ragged army.

Houston could not spare the number of men necessary to mount a successful defense. Instead, he sent Col James Bowie with 30 men to remove the artillery from the Alamo and destroy the complex. Bowie was unable to transport the artillery since the Alamo garrison lacked the necessary draft animals. Col James C. Neill (Alamo Commander) soon persuaded Bowie that the location held strategic importance. In a letter to Gov. Henry Smith, Bowie argued that the salvation of Texas depended in great measure on keeping Béxar out of the hands of the enemy.

Houston could not spare the number of men necessary to mount a successful defense. Instead, he sent Col James Bowie with 30 men to remove the artillery from the Alamo and destroy the complex. Bowie was unable to transport the artillery since the Alamo garrison lacked the necessary draft animals. Col James C. Neill (Alamo Commander) soon persuaded Bowie that the location held strategic importance. In a letter to Gov. Henry Smith, Bowie argued that the salvation of Texas depended in great measure on keeping Béxar out of the hands of the enemy.

It serves as the frontier picquet guard, and if it were in the possession of Santa Anna, there is no stronghold from which to repel him in his march towards the Sabine. The letter to Smith ended, Col Neill and I, have come to the solemn resolution that we will rather die in these ditches than give it up to the enemy. Bowie also wrote to the provisional government, asking for men, money, rifles, and cannon powder. Few reinforcements were authorized; cavalry officer Col William B. Travis arrived in Béxar with 30 men on Feb 3, 1836. Five days later, a small group of volunteers arrived, including the famous frontiersman and former US Congressman David Crockett of Tennessee. Houston, coolly logical, ordered Col William Travis and Col James Bowie to abandon the Alamo and blow up the magazine. The post was militarily indefensible, and to allow a whole battalion of splendid fighters to be trapped and destroyed was folly. Travis ignored the order, answering Santa Anna’s call to surrender with a cannon shot. His men stood defiant to the end, inflicting fearful losses on Santa Anna’s best troops. Houston gained two precious weeks to discipline and train his army, and when he faced the Mexican dictator at San Jacinto, the Alamo ghosts marched with him. Travis had been right after all, and at the sight of the vengeful Texans waving knives and hatchets and shrieking Remember the Alamo, the Mexican army dissolved into a mob of terror-stricken fugitives.

Maj Parker’s little band was a mixed force. In addition to his own 589-FAB, he found or was sent some half-tracks with .50 caliber quad mounts, a few armored field artillery observers, a tank destroyer platoon, one parachute infantry rifle squad, a cavalry recon section, and later one glider rifle company. In all, less than 300 soldiers. He clearly realized, as his higher headquarters did not, that he stood on critical terrain. The Baraque de Fraiture stands at the crossing of the main road from Bastogne in the south then through Houffalize and up north to Liège, with a good paved road westward from Vielsalm through La Roche en Ardennes. Moreover, the Liège road was the exact boundary between the flank divisions of two corps, neither one able to hold the road in strength. Loss of the junction would permit the Germans to move in either of three directions to flank or penetrate the US 1-A line. It could mean disaster. Thus, at about 1600 on December 20, Parker’s force went into position following what he considered to be competent orders from a higher authority to organize a strong point and fire on approaching enemy forces. Initial supplies of rations, fuel, and ammunition had been drawn at Vielsalm. Parker’s force was ready for action.

Maj Parker’s little band was a mixed force. In addition to his own 589-FAB, he found or was sent some half-tracks with .50 caliber quad mounts, a few armored field artillery observers, a tank destroyer platoon, one parachute infantry rifle squad, a cavalry recon section, and later one glider rifle company. In all, less than 300 soldiers. He clearly realized, as his higher headquarters did not, that he stood on critical terrain. The Baraque de Fraiture stands at the crossing of the main road from Bastogne in the south then through Houffalize and up north to Liège, with a good paved road westward from Vielsalm through La Roche en Ardennes. Moreover, the Liège road was the exact boundary between the flank divisions of two corps, neither one able to hold the road in strength. Loss of the junction would permit the Germans to move in either of three directions to flank or penetrate the US 1-A line. It could mean disaster. Thus, at about 1600 on December 20, Parker’s force went into position following what he considered to be competent orders from a higher authority to organize a strong point and fire on approaching enemy forces. Initial supplies of rations, fuel, and ammunition had been drawn at Vielsalm. Parker’s force was ready for action.

So far, so good but after several successful fire missions, Parker was ordered to displace north-east to Bra-sur-Lienne. In all fairness, the junction’s importance also was initially overlooked by both, the 3-AD and the 82-A/B sharing that boundary. Only later, after much action, did it gain its tactical title of Parker’s Crossroads. The major’s decision to ignore the order, or more subtly, to delay until execution became impossible, lifts this action into the ranks of intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty.

So far, so good but after several successful fire missions, Parker was ordered to displace north-east to Bra-sur-Lienne. In all fairness, the junction’s importance also was initially overlooked by both, the 3-AD and the 82-A/B sharing that boundary. Only later, after much action, did it gain its tactical title of Parker’s Crossroads. The major’s decision to ignore the order, or more subtly, to delay until execution became impossible, lifts this action into the ranks of intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty.

He seems to have reached the decision alone. Capt Arthur C. Brown, the third-ranking officer at the scene and the only firing battery commander to have escaped the earlier battalion ambush, wrote: Major Parker, was ordered to withdraw from this untenable position, but he delayed doing so because he probably sensed the importance of dividing up the enemy at this point. Further, he did not want to leave the people from other outfits there by themselves (he did not give me a vote!). It wasn’t long before we reached the line of no return, as we became surrounded. Parker knew that a powerful enemy armored and mechanized infantry force lay 6000 M west at Samrée, for he had laid observed fire on it that morning. More armor was approaching up the road from the south, and his supply route through Regné then Vielsalm, some 10.000 M east, was bare of support traffic. They were at the end of a very long limb. The terrain around the crossroads is deceptively flat though it stands on one of the highest elevations in the Belgian Ardennes, with broad, open fields of fire in all directions. But two large stands of evergreen woods afford easily infiltrated, concealed routes of approach nearly down to the junction. Once an enemy cut the road north to Manhay, only 6000 M to the rear, the crossroads became a trap. Escaping on foot through the snow would have been extremely difficult and by a vehicle on the road an impossibility. On the other hand, the deep snow and trees tended to canalize enemy movements and the howitzers were laid for direct fire down the three roads, the roads to Samrée, the one to Houffalize, and the one to Vielsalm.