And although they would be used like the infantry tanks in the breaching of the enemy line, it was to enable the Celere to penetrate the enemy line rather than to destroy the line itself. The new concept did not adequately deal with the problem of tank-versus-tank combat and even expected Italian tanks to fire main guns while on the move. An Italian study of the German Blitzkrieg emphasized that the armored division was designed for flanking attacks in a war of maneuver, and not for frontal attacks except in the most exceptional cases.

And although they would be used like the infantry tanks in the breaching of the enemy line, it was to enable the Celere to penetrate the enemy line rather than to destroy the line itself. The new concept did not adequately deal with the problem of tank-versus-tank combat and even expected Italian tanks to fire main guns while on the move. An Italian study of the German Blitzkrieg emphasized that the armored division was designed for flanking attacks in a war of maneuver, and not for frontal attacks except in the most exceptional cases.

Infantry: (a). Emphasis was placed on training sharpshooting, agile, and light infantry. For additional mobility, Bersaglieri were issued with folding bicycles that could be strapped on their backs.

(b). The Italian infantry battalion consisted of three rifle companies and a machine gun company of 12 guns. Each rifle company was divided into three platoons of two squads of 20 men each. One light automatic weapon was allocated per squad but the combat of the squad was not tied to that particular weapon. In the advance, the Italian platoon moved forward in two long squad worms with the light machine gun at the head of each. Upon encountering effective enemy fire, the squad riflemen would fan out to the right and left, respectively, seeking to maneuver around each flank, assaulting from both sides if necessary. The squads of 20 were further broken down into fighting groups of 3 to facilitate better control and more flexible movement. Throughout the encounter action, the squad light machine guns, supported by heavy machine guns from the rear, were to keep the enemy pinned down. It was a precept of Italian operations that heavy machine gun suppressive fire was necessary for the infantry to advance at all. Surprisingly, Italian doctrine recommended narrow attack frontages of 50 yards for a platoon and 400 yards for a battalion. Such frontages were, in Liddell Hart’s opinion bound to have a corpse-producing effect under modern conditions.

It was a precept of Italian operations that heavy machine gun suppressive fire was necessary for the infantry to advance at all. Surprisingly, Italian doctrine recommended narrow attack frontages of 50 yards for a platoon and 400 yards for a battalion. Such frontages were, in Liddell Hart’s opinion bound to have a corpse-producing effect under modern conditions.

(c). A British appraisal: the principal characteristic of Italian tactics in both theaters Libya and East Africa, has been rigidity. They have remained attached to one principle, the concentration of the greatest possible mass for every task that faces them. In the attack they deploy this mass in line and rely solely on weight on numbers to clear the way. If stalled, Italian units sought to regain momentum by committing their reserves frontally to reinforce failure. Deficiency of training, land navigation, off-road mobility, and logistics precluded flanking maneuvers, and a left frontal attack was the sole option. Lack of training and leadership prevented them from adopting the German infiltration tactics of 1917-1918 that became the heart of every other army’s small unit tactics. In the desert, infantry was capable only of static defense and was poorly equipped even for that. In hilly or mountainous terrain, Italian infantry did remarkably well.

Manpower Pool: Manpower came mostly from peasant stock. The personnel pool was handicapped by many local dialects. The masses were not highly educated. They were not mechanically experienced. Gasoline cost 4 times British prices so Italy had an automotive base of only one motor vehicle for every 130 people. In comparison, France had a ratio of 1/23, Britain 1/32, Germany 1/37, and the USA 1/4.4. Italy had, however, a manpower pool  with two excellent qualities, the willingness to suffer inadequate clothing, food, and supplies and the willingness, if led with anything approaching competence, to fight and die in conditions that would have caused the armies of the industrial democracies to quail. This manpower was misused as Italy followed the fairly common policy of subordinating infantry to other specialties in quality of personnel.

with two excellent qualities, the willingness to suffer inadequate clothing, food, and supplies and the willingness, if led with anything approaching competence, to fight and die in conditions that would have caused the armies of the industrial democracies to quail. This manpower was misused as Italy followed the fairly common policy of subordinating infantry to other specialties in quality of personnel.

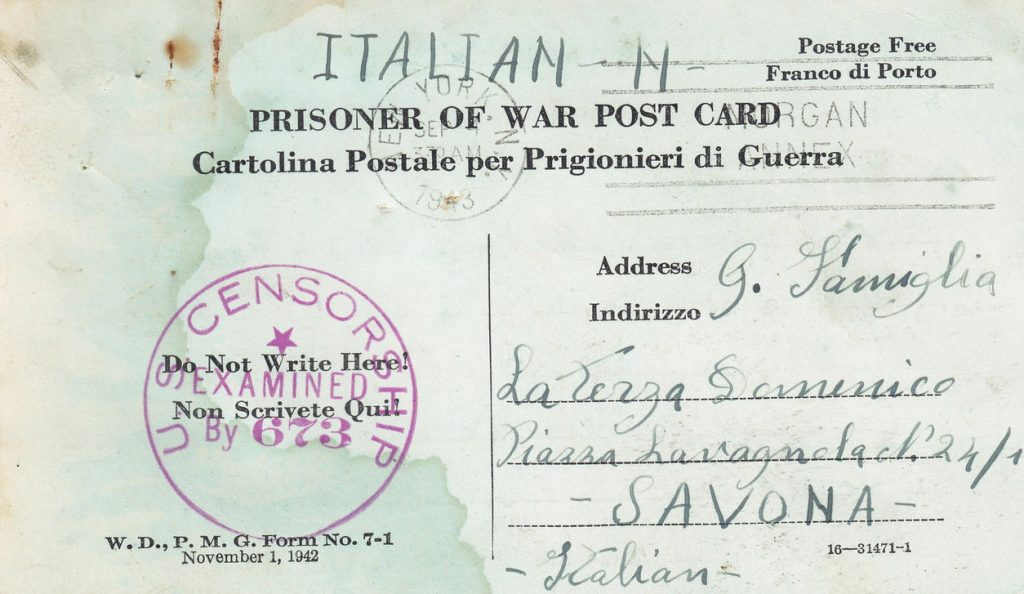

Conditions of Service: A policy stemming from the 1870s based on fears of mutiny and regional secession resulted in the members of each regiment being recruited from several different regions and stationed in yet another region. This caused friction and a lack of trust because of different regional dialects, values, and customs. Officers enjoyed better food, uniforms, and living conditions. They had EM assigned to them as servants. Little consideration was given to the other ranks. Their rations were universally described as the worst of all armies. Little thought was given to medical attention, mail, leave, and other factors of pride and morale. Italian mobile kitchens were wood-burning relics of 1907 in a treeless desert.

Rotation: British Command, even in quiet periods, did not keep its units in the front line for more than twelve days and, after that, gave them four days’ complete rest in the rear. On the other hand, our soldiers had for months not had any relief from front-line duty; rest was almost unknown to them, as was also the system of relieving for home leave units tired and worn from many months of exhausting life and combat in the desert. There were divisions amount the soldiers that had been fighting for more than twenty-four months in the front line, and that had greatly exceeded the theoretical 200 days which American and British experts have set as the maximum limit of physical and psychological resistance in battle, after which, according to them, the soldier becomes exhausted and militarily inefficient.

If the Italian soldier, deprived of means and exhausted has retreated before the superior numbers, strength, and buoyant morale organization of the enemy – if he has retreated it is because the limits of human endurance have been exceeded and he could not do otherwise. The Italian army was unspectacular and not overly successful, so the individual courage of the Italian soldier was emphasized to give a sense of national pride.

Training: Units were trained for service in the type of terrain in which they were most likely to serve. Great stress was placed on the cooperation of different arms, especially between infantry and artillery. For a war of movement, infantry command was greatly decentralized with platoons and sometimes squads acting largely on their initiative during offensives. The integration of all arms was desired, but inadequate technology and training limited the effectiveness of cooperation. In the offense, artillery was  frequently unable to cover or communicate with the infantry. In the defense, support was generally more effective. Personnel assigned to support and headquarters units were not given any infantry training whatsoever. They made absolutely no effort to provide all-around defensive perimeters to protect against raids or penetrations. Consequently, service troops were easily routed by minimal enemy forces. The instructions of the Chief of Staff to a commander sent to Libya in 1937 cautioned him not to do too much training. It was assumed that initiative and individual valor counted for far more than training.

frequently unable to cover or communicate with the infantry. In the defense, support was generally more effective. Personnel assigned to support and headquarters units were not given any infantry training whatsoever. They made absolutely no effort to provide all-around defensive perimeters to protect against raids or penetrations. Consequently, service troops were easily routed by minimal enemy forces. The instructions of the Chief of Staff to a commander sent to Libya in 1937 cautioned him not to do too much training. It was assumed that initiative and individual valor counted for far more than training.

OJT was the norm … even for such duties as tank drivers and gunners. The officer corps’ store of talent and experience was so diluted and so outdated that even training attempted did not accomplish a great deal. Some training, like that of the Bersaglieri, was quite impressive. Liddell Hart gained the distinct impression that the Italian military was training an army of human panthers, the physical training of the soldiers being far superior to anything ever seen. He described the marching endurance of the Italian soldier as astonishing.

Officers were overage. Promotions were under a strict seniority system. Officer pay and benefits were high at the expense of junior officer training. This lack of training resulted in over supervision. Bloated staff attempted to justify their existence. Older commanders led to atavistic intellectual narrowness. The proportionately high budget for regular officers also cut funds for weapons, and vehicles, and even economized at the expense of junior officer development.

Evaluation of Italian Wartime Officers: In a wartime study, Gen Mario Roatta, himself a major contributor to the problem, found the following deficiencies in the Italian officer corps: Lack of command authority, timidity, inadequate technical knowledge, poor understanding of communications equipment, poor map reading and use of a marching compass, lack of knowledge about field fortifications and fields of fire, poor physical conditioning, total administrative ignorance. Some effort was made to correct these deficiencies in junior officers. No such effort was made to improve senior ranks. A German staff officer evaluated Italian staff work: the command

Evaluation of Italian Wartime Officers: In a wartime study, Gen Mario Roatta, himself a major contributor to the problem, found the following deficiencies in the Italian officer corps: Lack of command authority, timidity, inadequate technical knowledge, poor understanding of communications equipment, poor map reading and use of a marching compass, lack of knowledge about field fortifications and fields of fire, poor physical conditioning, total administrative ignorance. Some effort was made to correct these deficiencies in junior officers. No such effort was made to improve senior ranks. A German staff officer evaluated Italian staff work: the command  structure is … pedantic and slow. The absence of sufficient communication equipment renders the links to the subordinate units precarious. The consequence is that the leadership is poorly informed about the friendly situation and cannot redeploy swiftly. The working style of the staff is schematic, static, and come cases lacking in precision.

structure is … pedantic and slow. The absence of sufficient communication equipment renders the links to the subordinate units precarious. The consequence is that the leadership is poorly informed about the friendly situation and cannot redeploy swiftly. The working style of the staff is schematic, static, and come cases lacking in precision.

The overabundance of older senior officers cultivated an atmosphere of intellectual rigidity and lack of curiosity. The Army began with two mistaken assumptions it had held fiercely through the interwar period: that the Alps were the most likely theater of war and that numbers were decisive. The first assumption fell away in 1940. The second, despite repeated demonstrations of its fallaciousness, determined Italian doctrine and force structure … and hence use of technology … until 1943.

Gen Ettore Bastico evaluated reserve officers: divisional commanders were unanimous in informing me that while subalterns, apart from a few exceptions, are rendering good service – even when they come from auxiliary sources, the same cannot be said for the majors and captains recalled from the reserve. These latter in general are too old, and even if they have the will and spirit of sacrifice they lack the energy and the capacity necessary for carrying out their duty. Also, nearly all of them reached their rank by successive promotions, the fruit of very brief periods of service. They were also unanimous in lamenting the fact that these officers, nearly all of them, come unprepared and therefore unsuited for the command of their units, or they suffer from congenital illnesses and after the briefest stay they have to be removed – because of professional incapacity or poor health.

Senior officers were not culled after World War One, and the junior officers were gutted during the 1920s by the thousands in a cost-cutting move. Italy was faced with a choice then to either cut the generals (and their higher salaries) or the lower officers and Italy made the wrong choice. Of junior officers Gen Claudio Trezzani observed as long as it’s a question of risking one’s skin, they are admirable, when, instead, they have to open their eyes, think, decide in cold blood, they are hopeless. In terms of reconnaissance, movement to contact, preparatory fire, coordinated movement, and so on, they are practically illiterate …

Officer Casualties: During World War Two, Italy lost 68 Generals, 84 Colonels, 10 Admirals, 30 naval Captains, 11 air force Generals, and 22 air force Colonels. Surely the sacrifice of one’s life imposes respect, but it is not a measure of professional ability. Prof Lucio Ceva.

Evaluation: Feldmarschall Erwin Rommel: the Italian soldier is disciplined, sober, an excellent worker, and an example to the Germans in preparing dug-in positions. If attacked he reacts well. He lacks, however, a spirit of attack, and  above all, proper training. Many operations did not succeed solely because of a lack of coordination between artillery and heavy arms fire and the advance of the infantry. The lack of adequate means of supply and service, and the insufficient number of motor vehicles and tanks, is such that during some movements Italian sections arrived at their posts incomplete. Lack of means of transport and service in Italian units is such that especially in the bigger units, they cannot be maintained as a reserve and one cannot count on their quick intervention.

above all, proper training. Many operations did not succeed solely because of a lack of coordination between artillery and heavy arms fire and the advance of the infantry. The lack of adequate means of supply and service, and the insufficient number of motor vehicles and tanks, is such that during some movements Italian sections arrived at their posts incomplete. Lack of means of transport and service in Italian units is such that especially in the bigger units, they cannot be maintained as a reserve and one cannot count on their quick intervention.

Equipment: The unsuitability of much of the Italian equipment was caused by multiple reasons. Equipment must be designed to perform the function demanded of it by doctrine. When doctrine is changed, it only follows that some of the equipment will no longer be suitable. Equipment must be designed to perform in the environment envisioned. When operations are conducted in areas not planned for and prepared for, some of the equipment will not be suitable. National pride and balance of payments frequently see nations adopt an inferior design just because it is designed and produced at home. There are some reports of corruption and collusion within the Italian military-industrial complex. The armed forces of every nation suffer these problems to some extent, but Italy lacked the economic and industrial foundation to effect timely changes.

To ease his balance of payment problems, Mussolini had sold off his newest aircraft and weapons to foreign buyers like Spain and Turkey while equipping his forces with old 1918 field guns. The army had to borrow trucks from private firms just to hold peacetime parades of its motorized divisions. Italian troops were also short of antitank guns, antiaircraft gun ammunition, and radio sets. Artillery was light and ancient.

To ease his balance of payment problems, Mussolini had sold off his newest aircraft and weapons to foreign buyers like Spain and Turkey while equipping his forces with old 1918 field guns. The army had to borrow trucks from private firms just to hold peacetime parades of its motorized divisions. Italian troops were also short of antitank guns, antiaircraft gun ammunition, and radio sets. Artillery was light and ancient.

Small Arms: The Beretta pistol and submachine gun were outstanding weapons, but the Mannlicher-Carcano rifle, a rather indifferent model designed in 1881, suffered from low bullet velocity. The Breda M-1930 light machine guns were clumsy to operate and jammed easily. The war caught Italy in the process of changing from the 6.5-MM to a 7.35-MM round. They tried to revert to the older and more common round. The Model 35 Red Devil hand grenades had a cute trick of exploding in the hands of their users.

Crew Served Weapons: The Breda M-1937 machine gun was strip fed and complicated to the extent that the empty brass was re-inserted into the strips. Ammunition was oiled. This attracted dust and caused malfunctions. Ammunition was of caliber 8-MM which was different from the LMG and rifle ammunition.

Mortar: Italy’s 45-MM Brixia mortar might have been quite useful in World War One, but, like small mortars of some other nations, was not well suited to conditions that developed during the Second World War. The 81-MM piece was an excellent weapon and was well suited for mountain warfare, but was claimed by range to be of little use in the desert.

AT Guns: The war in Spain had proven the 47-MM Bohler inadequate, but the elderly (1913) 65-MM infantry gun, once the Alpini’s pack artillery, had worked and was praised for its lightweight as well as its omnipresence.

AT Guns: The war in Spain had proven the 47-MM Bohler inadequate, but the elderly (1913) 65-MM infantry gun, once the Alpini’s pack artillery, had worked and was praised for its lightweight as well as its omnipresence.

No attempt was made to improve this situation because Italy was indeed barely able to equip all units with the obsolescent Bohler. Italian officers failed to appreciate the true seriousness because they thought that Spain was not reflective of full-scale warfare. They expected more heavy artillery, more chemical warfare, and more well prepared fixed defenses than Spain provided.

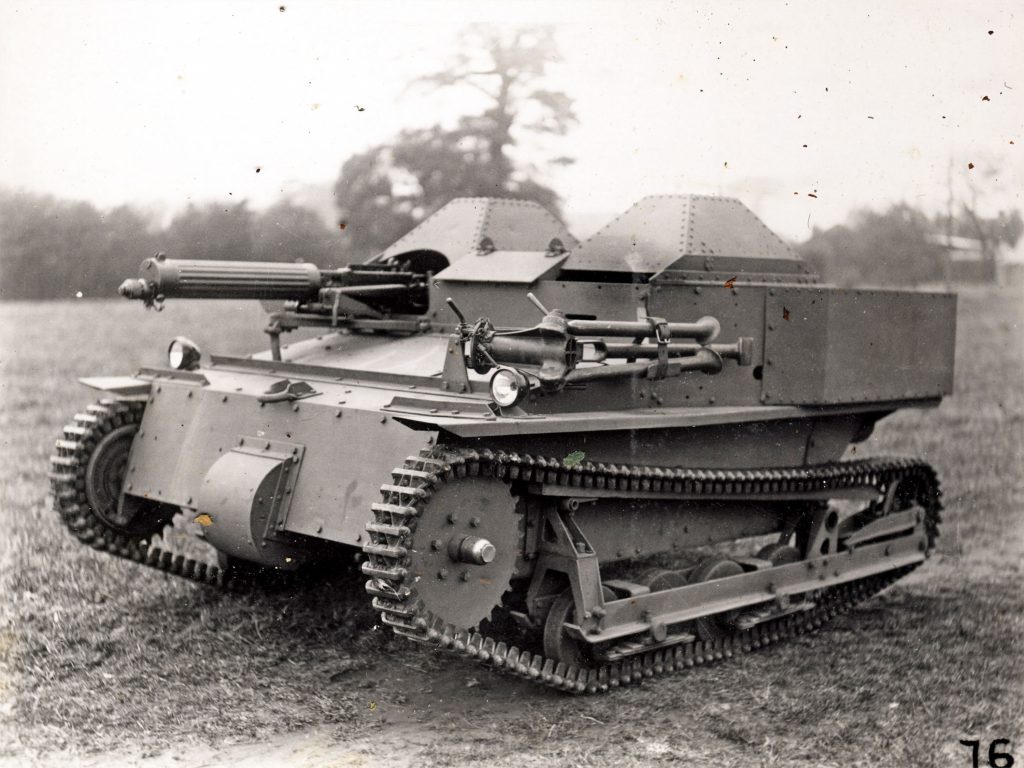

Tanks: Italy began rearming earlier than the other powers. Unfortunately for their armored force, this was when tankettes were in vogue. The L/3 was very reliable, quite mobile, and, with over 2000 in inventory, in an abundance that precluded easy access to funds for newer weapons systems. The 3.5-ton vehicle was, sadly, an under-protected, machine gun-armed tankette with little business on a WW-II battlefield. The underpowered and thinly armored M-11/39 suffered from the main gun’s being hull-mounted because narrow Italian roads and railway tunnels would not permit a turret width sufficient to accept a gun. The heavyweight M-13 packed a turret-mounted 47-MM gun but crawled along at nine miles per hour.

Artillery: The artillery was equipped with the 1914-1918 Austrian field pieces refurbished in 1933. A modernization plan was delayed for 10 years due to new naval construction and foreign adventures and thus was not to be completed until 1950 …  This meant that Italy’s gunners faced opponents with greater range, greater mobility, and a greater rate of fire.

This meant that Italy’s gunners faced opponents with greater range, greater mobility, and a greater rate of fire.

Motorcycles: The idea of motorized infantry being mounted on motorcycles was a legacy of the bicycles and motorcycles used successfully by the Bersaglieri in the First World War. This also meant that a very competent and highly respected light infantry force would evolve into a rather inefficient motorized infantry, but, the Bersaglieri on his motorcycle with his plume blowing in the wind was a powerful image to Italians, including that old Bersaglieri himself, Benito Mussolini. Attempts were made during the war to carry some of these troops in trucks, but the Italian automotive industry was not up to the task.

Bicycles: The bicycle had arrived as a military item in the 1880s and 1890s… The Italians raised the use of the military bicycle to its highest level. The bicycle troops were essentially a mounted infantry unit without a requirement for forage. They could be used as couriers, scouts, or in other traditional cavalry roles. The Italians prided themselves on the speed with which Bersaglieri-cyclisti could maneuver. Bicycle troops became almost a culture in the late ‘30s and early ’40s. The bicycle, based on Italy’s WW-I record, was competing with armored vehicles as battlefield transportation.

Communications: Reliance was on the landline. Even common wire was in short supply. No effort was made to put radios in tanks until 1942. Italian units lacked armored cars with radios to keep tabs on enemy units. Radio  equipment available to corps, divisions, and higher would not function on the move, required a long set up time, and didn’t work at all under conditions of the Russian front. Signal communications were, unique among armies, a function of the engineer troops.

equipment available to corps, divisions, and higher would not function on the move, required a long set up time, and didn’t work at all under conditions of the Russian front. Signal communications were, unique among armies, a function of the engineer troops.

Conclusion – The Hope

The mechanization of Italy’s army was a goal determined before the war. Only two armies in Europe envisioned a role for armored corps—Germany and Italy. Italy, therefore, began the war ahead of most other nations in doctrine. Britain and France did not have the armored striking force that Italy possessed. Only one brigade of quasi-armored troops existed in the United States. Only Germany had a superior armored force, but the Italian Centauro armored division, used against Albania, beat the Germans by several months being the first armored division to be operationally employed. The Guerra di Rapido Corso would have dared to attempt mechanized warfare in mountainous terrain. Celere units were envisioned as flanking units and pursuit units. They were combined with motorized infantry and armored divisions making the breakthrough and with the alpine divisions covering the flanks, it was a novel and a heady concept. It remains an untested concept.

The Reality : In the cold, hard world of economic and industrial capability, Italy’s inadequacies limited the possibilities. Italy lacked the essential raw materials and industrial base to be a major power. Her annual production of 2.4 million tons of steel, for example, paled when compared with Japan’s 5 million tons, Britain’s 13.4 million tons, and Germany’s 22.5 million tons.

The Reality : In the cold, hard world of economic and industrial capability, Italy’s inadequacies limited the possibilities. Italy lacked the essential raw materials and industrial base to be a major power. Her annual production of 2.4 million tons of steel, for example, paled when compared with Japan’s 5 million tons, Britain’s 13.4 million tons, and Germany’s 22.5 million tons.

Italy’s financial difficulties were made worse by Mussolini’s mismanagement. His adventures in Spain and Ethiopia had been a tremendous drain on the treasury. His formation of the Fascist Militia did not pay good dividends. Blackshirt units did not perform well and siphoned away material that the exiting armed forces needed desperately. Italian armed forces had some serious problems. They were poorly organized, equipped, led, and trained. They had been prepared for the wrong war. This was certainly not unique among nations, but Italy lacked the favorable geography and the industrial might of the nations that we’re able to overcome similar difficulties. Marshal Badoglio, in an audience with the king in March 1943 explained, when war is made on the explicit calculation that it will be short and if the preparations are for a lightning war, it is lost as soon as the opposite happens.

Italy entered the war with old generals, no heavy tanks, mechanically unreliable and uncomfortable medium tanks, a lack of motor vehicles and drivers for them, old artillery, and preparations to fight a war in the Alps against the French or to invade Yugoslavia — not for a war in the desert or Russia. Her Navy was built to face the French not the British and had been told not to expect to resupply North Africa.

One of the first tasks assigned to the Navy was to resupply North Africa! Her Air Force was too small and, geared to Douhet’s doctrine of gas attacks against cities, armed with too few bombers, protected by under-gunned and low powered fighters.

English, John, A Perspective on Infantry

Greene, Jack, Mare Nostrum

Knox, McGregor, Hitler’s Italian Allies

Lippman, David H., Desert Dawn

Millett and Murray, Military Effectiveness vol.3

Ogorkiewitz, Richard, Armour

Solitario, Lupo Information from the internet

Sweet, John Joseph Timothy, Iron Arm

Tyre, Rex, Mussolini’s Soldiers

US Army, TM 30-420, Handbook of Italian Military Forces

Text & Researches, Woody Turnbow