Regardless of constraints imposed by the newly arrived ECOs, most importantly the ‘milking’ of units was carried out on a great scale. The Army memorandum on recruitment states that; the new battalions will be raised from personal to be ‘milked’ from active battalions of regiments concerned. (80) In this case, Marston argues: Various regular units were milked of regular men and officers for the rapidly expanding army; as recruits were raised, the regular units would be asked to provide a certain number of officers and men to send as a cadre to the new unit. (81)

Regardless of constraints imposed by the newly arrived ECOs, most importantly the ‘milking’ of units was carried out on a great scale. The Army memorandum on recruitment states that; the new battalions will be raised from personal to be ‘milked’ from active battalions of regiments concerned. (80) In this case, Marston argues: Various regular units were milked of regular men and officers for the rapidly expanding army; as recruits were raised, the regular units would be asked to provide a certain number of officers and men to send as a cadre to the new unit. (81)

The Gurkha Brigade more than doubled its strength during the war, but to do so its cadre of trained and experienced VCOs and NCOs, not to mention British officers, had to be spread dangerously thin. (82) In the first stage of expansion, the 4/8th Gurkha’s raised in 1941, initially had to bring two hundred men and Officers from other battalions. The 5th Gurkha’s regimental history claims that a degree of nucleus sharing had to be given to each newly raised battalion while itself was under strength. (83) Desperately the Gurkha Brigade grappled with the problem (84), as the original battalions drained out of experienced staff when the newly raised battalions had not enough of them.

For the ‘Target 43’ expansion, more Indian manpower was needed to recapture Burma. In the other case, British manpower was stretched out extensively to other theaters of war, and importantly, the planning of D-Day caused much preparation of specialized units. Raw manpower for infantry was available sufficiently in India. However, the only shortages were of specialized units. As a result, the expansion target for 1943 was based on the possibility of producing the maximum number of Indian administrative units to relieve British units in Eastern theaters and thus help to conserve British manpower. (85) Native Indians were allowed to enlist in specialized units like tanks however Gurkhas were restricted. Few joined artillery regiments, but the Gurkha regiments still stood as a light infantry unit. The view was that an uneducated highlander was incapable of functioning in specialized units. The specialized roles within the battalion were mostly reserved for Line Boys’.

As more priority was given to specialized training, a centralized training division was established, ceasing the existing regimental training system. Because of a newly introduced training system, each native Indian training battalion was allocated to two regiments. In the case of the Gurkhas, however, this was not done, and the new battalion had to be formed. (86) It caused a further diversion of experienced Officers and NCOs. Not only does it drains out the capable manpower, thinning out of highly skilled VCOs and NCOs, caused a serious problem in the discipline of men, as supervision had  been exercised less frequently. Kehi hokum payenna (I did not have any orders) was often the men’s excuse if summoned by seniors. (87) The excellence of potential recruits was affected. A Gurkha training instructor states, Centre ma recruit Haru ta ankha kan ani khutta langada nabhako bahek sabbai bharti hunthiyo (only the boys who did not have an adequate quality of optical and hearing power, and deformed leg could not be recruited, the rest could be recruited). (88) In this case, the ‘Target 41’ expansion enjoyed recruiting high-quality recruits, but the ‘Target 43’ faced problem, in finding suitable recruits from the traditional recruiting area.

been exercised less frequently. Kehi hokum payenna (I did not have any orders) was often the men’s excuse if summoned by seniors. (87) The excellence of potential recruits was affected. A Gurkha training instructor states, Centre ma recruit Haru ta ankha kan ani khutta langada nabhako bahek sabbai bharti hunthiyo (only the boys who did not have an adequate quality of optical and hearing power, and deformed leg could not be recruited, the rest could be recruited). (88) In this case, the ‘Target 41’ expansion enjoyed recruiting high-quality recruits, but the ‘Target 43’ faced problem, in finding suitable recruits from the traditional recruiting area.

As a result, previous recruitment criteria obliged that the potential recruits had to be dropped sharply. The only obvious criterion demanded, was that individuals must be in a capable physical condition. Despite the sharp decline in the quality of recruits, the number of volunteers also decreased sharply to the ‘Target 43’. Native Indian units adopted the expansion of recruitment policies to include men from the so-called ‘non-martial race’ in 1940; however, the Gurkha Brigade came to follow the same pattern only in the second phase of expansion. Except in the new classes, the general quality of the recruits is tending to decline both in physique and intelligence. (90) Due to the obvious problems of rapid expansion overstraining the resources of traditional recruitment areas, (91) and its effect on the quality and quantity of recruits, it was essential for the Brigade to accept Gurkhas from ‘non-martial’ races and opening new areas for recruitment, which had been hitherto prohibited. (92)

Previously, the recruitment handbook of the Gurkhas advised the recruiting officials that; no recruit from Tehsil N°1 East or N°1 West on any account be bought in; these areas are reserved for recruiting by the Nepalese Army. (93)

The GHQ India termed these recruits from the non-traditional area as ‘untied recruits’, which had to be accepted as the Gurkha units drained out of quality recruits from the traditional areas. However, the permission to increase the recruitment areas had not been granted as straightforward. During a low period for Britain, in the context of the war progression, few questions from the Nepalese Maharaja had been raised over the capacity of the British Army. The local population from the traditional recruitment areas was increasingly reluctant to the concept of recruitment, as the stories were full of horror and spread in the villages from returning Gurkhas. Also, rumors within villages maintained that if Britain lost the war, none of the Gurkhas would be eligible for a pension. Mainly, to answer the questions raised by the Maharaja, Betham went on saying it had been caused by the ‘setbacks’; which, he blamed on the late rearmament of the British Army. (94)

The GHQ India termed these recruits from the non-traditional area as ‘untied recruits’, which had to be accepted as the Gurkha units drained out of quality recruits from the traditional areas. However, the permission to increase the recruitment areas had not been granted as straightforward. During a low period for Britain, in the context of the war progression, few questions from the Nepalese Maharaja had been raised over the capacity of the British Army. The local population from the traditional recruitment areas was increasingly reluctant to the concept of recruitment, as the stories were full of horror and spread in the villages from returning Gurkhas. Also, rumors within villages maintained that if Britain lost the war, none of the Gurkhas would be eligible for a pension. Mainly, to answer the questions raised by the Maharaja, Betham went on saying it had been caused by the ‘setbacks’; which, he blamed on the late rearmament of the British Army. (94)

Uprety claims, a six-point note of clarification explaining the actual Allied position in Europe in the conflict was provided. (95) It effectively obtained Nepal’s confidence in the British Army and released more recruitment areas by temporarily stopping the recruitment of the Nepalese Army. Gurung argues; that the intention of the utterly easy recruitment policy of the Maharaja was egocentric. The new policy did not propose to serve the British interest but to serve their autocratic rule, and they were rewarded accordingly. (96)

(80) Recruitment, L/WS/1/394, (IOR). (81) Marston. D.P, Phoenix from the Ashes, p 42. (82) Gould.T, Imperial Warriors, p 237. (83) The History of the 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles, p 49. (84) Bullock C, Britain’s Gurkhas, p 97. (85) Expansion, L/WS/1/968, (IOR). (86) The History of the 5thRoyal Gurkha Rifles, p 413. (87) Gould.T, Imperial Warriors, p 237. (88) Interview with a Gurkha soldier from 2/5 Gurkhas, accession no. 025152 to Major Beven’s interviews series. (89) Marston D.P, A force transformed in A military history of India, p 121. (90) Expansion, L/WS/1/968, IOR-British Library. (91) Marston. D.P, Phoenix from the Ashes, p 49. (92) Uprety P.R, Nepal, p 261. (93) Morris C.J, Gurkhas; Hand book, p 145. (94) Tuker F, Gorkha, p 214. (95) Uprety P.R, Nepal, p 238. (96) Gurung C.B, British Medals, and Gurkhas, p 11

On top of providing consensus to the House of Rana, against the backdrop of a growing democratic political movement to the Rana rule, the Government of India paid an annual fixed royalty of two million rupees during the period of WW-2. Nonetheless, the authorization of more recruiting areas directly benefitted the Gurkha Brigade, by receiving high qualities of recruits once again. It was a relief to the brigade, as a commander like Orde Wingate had already started to question Gurkhas’ fighting qualities after his ambitious First Chindits operation.

On top of providing consensus to the House of Rana, against the backdrop of a growing democratic political movement to the Rana rule, the Government of India paid an annual fixed royalty of two million rupees during the period of WW-2. Nonetheless, the authorization of more recruiting areas directly benefitted the Gurkha Brigade, by receiving high qualities of recruits once again. It was a relief to the brigade, as a commander like Orde Wingate had already started to question Gurkhas’ fighting qualities after his ambitious First Chindits operation.

Surely, the improvement in the qualities of the recruits helped to abolish the increasing threat to the Gurkhas’ reputation, by providing high-class recruits once again. Along with its increased size, since the first stage of expansion in 1941, it adopted the ever-changing training policies as the war progressed and demanded by the ever-changing nature of war.

The fighting in two theaters of war meant that it had to adopt different training manuals as the experiences of fighting in one theater did not help another. As Thinning-Out and Milking the units created considerable problems for the Gurkha Brigade, problems had to be rectified immediately as they threatened the reputation of the Gurkhas.

However, with the rapid expansion of the Gurkha Regiments and changes in recruitment policies, the Brigade of Gurkhas welcomed the tempo of war.

The Gurkhas – Middle East – North Africa – Italy

Initially, 1/5th Gurkhas completed its mobilization with the 17th Indian Infantry Brigade on May 24, 1941. However, as some core manpower had to be diverted to newly raised battalions, it required some time to build up its strength and, above all, to mechanize the battalion after the departure of the horses and mules. (97) Despite these shortages, the battalion left for the Middle East to join the 10th Indian Division. This marked the beginning of deployment for the Gurkha Brigade.

Initially, 1/5th Gurkhas completed its mobilization with the 17th Indian Infantry Brigade on May 24, 1941. However, as some core manpower had to be diverted to newly raised battalions, it required some time to build up its strength and, above all, to mechanize the battalion after the departure of the horses and mules. (97) Despite these shortages, the battalion left for the Middle East to join the 10th Indian Division. This marked the beginning of deployment for the Gurkha Brigade.

The 5th Gurkhas regimental history claims, much equipment arrived only a few days before entrainment, including Bren Guns, 3-Inch mortars, and AT rifles. (98) Despite the hostile condition, and the need to fight in battles, the battalion had to ensure that the soldiers were familiar with the new equipment. Concurrent training programs in the lull of battle were the only option left; which they adopted. The condition of battle was not much improved either, since the arrival of the first Indian troops in 1940. The Germans were continuing to infiltrate the Middle East, oil was at stake then, more than ever to support the emerging mechanized warfare.

Although there are many reasons, one important reason was that troops from the Indian Contingent increased dramatically in the Middle East. Elliott argues; due to the rapid and decisive action taken from India in April 1941 the German effort was stillborn, but the issue was, for a month, too nicely poised in the balance for comfort. (99) Upon arrival in Iraq, the Gurkha Regiments found hostile situations caused by pro-German forces. 2/4th GR, as they disembarked the Iraqis opened fire on them and killed up to a platoon’s worth. (100) Regardless of proper equipment, the Gurkhas carried on fighting from one city to another.

As a result of the lack of mosquito nets, soldiers did not have enough sleep, and in some instances, the attack on the Iraqi barracks carried on without proper sleep for many nights. (101) This mosquito terror caused serious problems in the later stage of the war. However, the 10th Indian Division made short work of the invasion and soon surrounded Baghdad. (102) The defeat of the pro-German force ensured the installment of the pro-British government as a replacement.

As a result of the lack of mosquito nets, soldiers did not have enough sleep, and in some instances, the attack on the Iraqi barracks carried on without proper sleep for many nights. (101) This mosquito terror caused serious problems in the later stage of the war. However, the 10th Indian Division made short work of the invasion and soon surrounded Baghdad. (102) The defeat of the pro-German force ensured the installment of the pro-British government as a replacement.

Simultaneously, the 5th Indian Brigade fought alongside the Free French Army and troops of the Australian Army, against the Vichy French Government in Syria.In a series of naval disasters, the Royal Navy had temporarily lost control of the Eastern Mediterranean, and the diversion of a complete air corps from the Russian Front meant that the German had air superiority. (103) Fighting without air support, let down by their allies resulted in massive casualties for the Gurkha Battalions. (104) Additionally, the heavy toll of malaria has taken into the 2/10 Gurkhas in Aleppo that it became temporarily ineffective for operation and had to be sent to Aden for treatment. (105)

In this instance, without a significant involvement with a first-class enemy, heavy casualties had been inflicted on Gurkha units. However, the German venture to spread Axis policies was brilliantly countered. Elliott argues if it was too late to react, and enemy reinforcement was allowed, British forces could have lost vital oil supplies in the Middle East, and intervention against the Russian flank around Rostov could have been possible; potentially threatening Russia from the south. Lunt argues; that the main concentration of British forces against the pro-German forces was because of the German occupation of the Caucasians. It was seriously considered that they might continue this offensive either to seize the Suez Canal or drive through Iran and Afghanistan towards India or both. (106) In this case, India was potentially in danger of invasions, from both Germany and Japan. Nevertheless, the original intention of the Axis forces failed, because of the excellent fighting spirit performed by Indian troops.

The official history of WW-2 asserts that the notable success was largely due to the fine qualities and conduct of the Indian troops, resolutely led. (107) Smith declares: After such beginning, the morale was high, although nearly six months were to elapse before the 1/2nd and 2/7th were called to join the already famous 4th Indian Division, under the command of Gen Gertie Tuker. (108)

The official history of WW-2 asserts that the notable success was largely due to the fine qualities and conduct of the Indian troops, resolutely led. (107) Smith declares: After such beginning, the morale was high, although nearly six months were to elapse before the 1/2nd and 2/7th were called to join the already famous 4th Indian Division, under the command of Gen Gertie Tuker. (108)

(97) Lunt, Jai Sixth, p 73. (98) 5 GR regimental history, p 49. (99) Elliott, Roll of Honour, p 82-83. (100) The Battle account of Bilbahadur Thapa, 2/8th Gurkhas in Gurkhas at War, p 128. (101) Interview with Gurkha Officer, Army No. 16216, 2/10th Gurkhas. (102) Parker. J, Gurkhas. (103) Bullock, Britain’s Gurkha, p 99. (104) Elliott, A roll of honor, p 100. (105) Interview with Gurkha Officer, Army No. 16216, 2/10th Gurkhas. (106) Lunt, Jai Sixth, p 74. (107) Playfair, I.S.O, The Mediterranean and the Middle East, V. II, (Her Majesty’s Stationary Service, 1956, London), p 212. (108) Smith, Brigade of Gurkhas, p 92

The 4th Division adopted a few changes to the composition of regiments in 1942, between the Middle East and North African forces, so that garrison units in Pairforce might benefit from their battle experience. (109) Stevens proclaims, the Divisional commander made a strong plea for the Gurkha units as replacements, with the result that the 2/7 Gurkha Rifles joined the 11th Brigade, and the 1/2GR joined the 7th Brigade. (110) The Western Desert Force of Gen Wavell had already inflicted heavy losses on the Italian Forces, before the arrival of Rommel, but the Gurkha Regiments were not a part of this early success.

Sixsmith argues, in the winter of 1940/1941 operations in Egypt and Libya showed the Italians to have little stomach for the war and the British, Australian, and Indian regular forces to be in every way their superior. (111) The series of Wavell’s victories over Italians finally dragged the German’s prioritization in General of North Africa. Rommel, taking over the command of the Afrika Korps won a series of brilliant victories which had forced the British Eighth Army to retreat in haste and disorder into Egypt. (112)

Withdrawing British forces failed to form a strong defense; in many cases, the defense was not even established properly. The shortages of equipment were rife among the men. Recently transferred Gurkha regiments were not confident with this kind of warfare in the desert either. It proves the composition of the desert force was not balanced to fight against a first-class enemy.

The 4th Gurkha Regiment’s history asserts; We had no experiences in the technique of mines or in working with tanks, both of which featured largely in this desert warfare. (113)

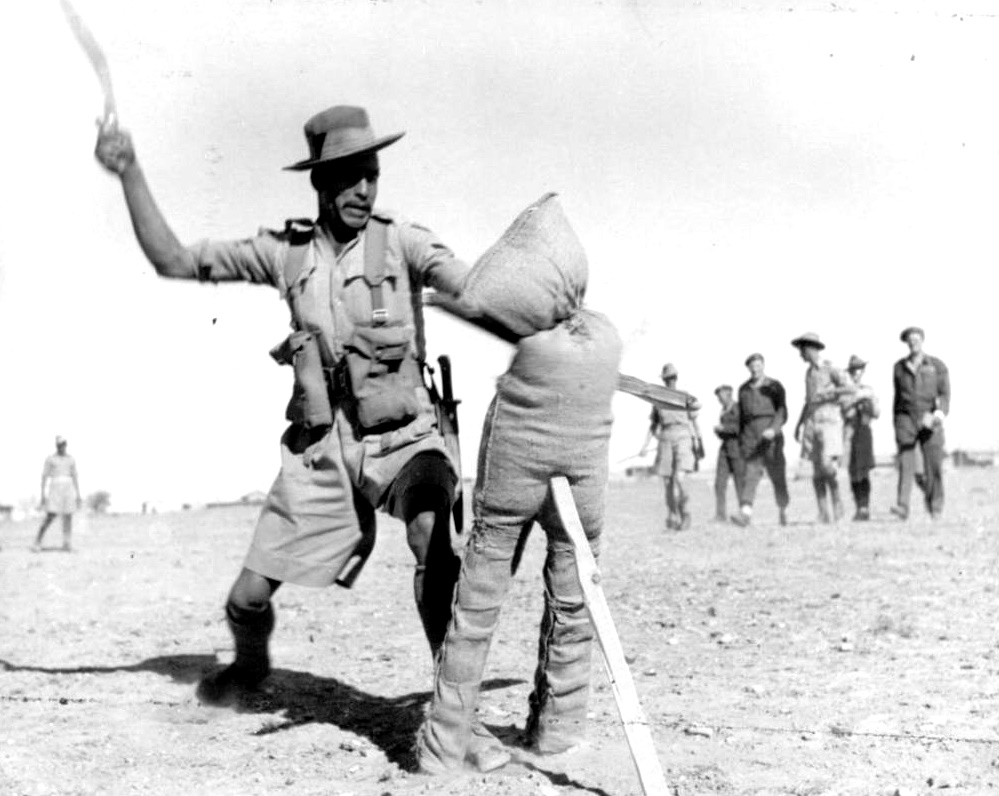

In India, the Gurkha Regiments did not see tanks, and the campaign in the Middle East was not with the first-class enemy; thus, the modern type of mechanized warfare was completely new to them. Despite the short intensive training before Rommel’s offensive began, men from the 2/4 Gurkhas were not confident with their equipment; especially with the newly introduced two-pounders and new hand grenades, most importantly they were not familiar with fighting as dismounted troops alongside large tanks units. They did not receive the right training, to prepare for this kind of mobile and mechanized warfare. Despite the mentioned underlying downfalls, the 2/4 Gurkhas, as part of the 10th Indian Infantry Brigade, were ordered to hold a box ‘Kennels’ at Bir Hacheim, along with the 2nd Battalion Highland Light Infantry and the 4/10 Baluch Regiment.

In India, the Gurkha Regiments did not see tanks, and the campaign in the Middle East was not with the first-class enemy; thus, the modern type of mechanized warfare was completely new to them. Despite the short intensive training before Rommel’s offensive began, men from the 2/4 Gurkhas were not confident with their equipment; especially with the newly introduced two-pounders and new hand grenades, most importantly they were not familiar with fighting as dismounted troops alongside large tanks units. They did not receive the right training, to prepare for this kind of mobile and mechanized warfare. Despite the mentioned underlying downfalls, the 2/4 Gurkhas, as part of the 10th Indian Infantry Brigade, were ordered to hold a box ‘Kennels’ at Bir Hacheim, along with the 2nd Battalion Highland Light Infantry and the 4/10 Baluch Regiment.

The front from Gazala to Bir Hacheim consisted of six brigade-sized defensive ‘boxes’ which, sheltering behind the minefield, were intended to hold any German Panzers Corps. (114) Mines were the most formidable defenses, as tanks and anti-tank weapons were not enough. British anti-tank guns were far inferior to their German foe. Kulman Pun asserts, for every shot we fired; German fired five back at us. (115) The 2/4 Gurkhas fought against the overwhelming German Panzers and artillery for 48 hours continuously without any reinforcement. Gumansing Thapa claims, first German aircraft bombed us and the Germans came on us from the rear and said ‘Hands up!’We had finished our ammunition by then, that fighting was not even an option. (116) The fall of the outer defense line, on Jun 6, 1942, directly allowed the advance of Rommel to Tobruk.

The 2/7 Gurkha Rifles was apart along with a light battalion of the Cameron Highlanders and a battalion of Mahratta Light Infantry in the 11th Brigade. (117) At worst, Smith claims that around the perimeter mines and wire had been removed for use elsewhere in Egypt. (118)

The 2/7 Gurkha Rifles was apart along with a light battalion of the Cameron Highlanders and a battalion of Mahratta Light Infantry in the 11th Brigade. (117) At worst, Smith claims that around the perimeter mines and wire had been removed for use elsewhere in Egypt. (118)

Thus, the German tanks and artillery drove through without any great resistance, and Stukas flocked without opposition from anti-aircraft weapons. First, the enemy weight fell into the position of Mahratta, then burst through the gap, split into two groups, and swung into the rear of the Cameron and Gurkha positions. (119) The Brigade HQ had been overrun already.

Having lost communication with other units, the Gurkhas and the Cameron fought until the last round, after the official surrender of the 11th Brigade. To which, Stevens claims, throughout the forenoon of Jun 21, isolated Gurkha posts without food or water held out under intense fire, where panzers waited for a kill in close range of a few hundred yards. (120) Despite the great effort performed by the remaining men, the 2/7th Gurkhas fell into German captivity for the second time in its history. Few men from other Gurkha Regiments managed to escape from the advancing German forces towards El Alamein, most of them, by their wit, strength, and guile. In such a chaotic situation and against the ever-watchful Germans that Durga Pun escaped to a friendly location under the command of his platoon Subedar. (121)

Gould argues, until the end of 1942 the experience of most Gurkha Battalions (which had taken no part in Wavell’s early victories over the Italians) was restricted to defeat and surrender. (122) Francis Tuker, in this case, blames the Generals for their conduct in the battles. Battalion after battalion of these Highlanders were being heaped into the ill devised, ill-conducted series of operations in the Western Desert from Gazala to Alamein where they, like all others, suffered heavily to no purpose whatsoever. (123)

In supporting the argument presented by Tuker, Fraser claims that Ther British equipment was inferior; that British training was inadequate, British organization and tactics faulty; that British generalship was remote and combat inexperienced. (124)

(109) Lt Col Stevens G.R, 4th Indian Division, (McLaren and Son Limited, 1948, Toronto) p 162. (110) Stevens, 4th Indian Division, p 162. (111) Sixsmith E.K.G, British Generalship in the Twentieth Century, (Arms and Armour Press, 1970, London), p 214. (112) Smith, Brigade of Gurkhas, p 92. (113) Lt Col. Borrowman C.G, A history of the 4th Prince of Wales’s Own Gurkha Rifles, V II, 1938-48, (William Blackwood & Sons Ltd, 1952, London), p 47. (114) Bullock, Britain’s Gurkha, p 99. (115) Cross and Gurung, Battle accounts of Kulman Pun, 2/3rd Gurkhas in Gurkhas at War, p 136. (116) ibid, p 140. (117) Bullock, Britain’s Gurkha, p 101. (118) Smith, Brigade of Gurkhas, p 93. (119) Stevens, 4th Indian Division, p 171. (120) ibid, p 174. (121) Interview with Durga Pun, 2/3th Gurkhas. (122) Gould, Imperial soldiers, p 238. (123) Tuker, Gorkha, p 217. (124) Fraser D, And we shall shock them, (Hodder & Stoughton, 1983, London), p 157-158

(109) Lt Col Stevens G.R, 4th Indian Division, (McLaren and Son Limited, 1948, Toronto) p 162. (110) Stevens, 4th Indian Division, p 162. (111) Sixsmith E.K.G, British Generalship in the Twentieth Century, (Arms and Armour Press, 1970, London), p 214. (112) Smith, Brigade of Gurkhas, p 92. (113) Lt Col. Borrowman C.G, A history of the 4th Prince of Wales’s Own Gurkha Rifles, V II, 1938-48, (William Blackwood & Sons Ltd, 1952, London), p 47. (114) Bullock, Britain’s Gurkha, p 99. (115) Cross and Gurung, Battle accounts of Kulman Pun, 2/3rd Gurkhas in Gurkhas at War, p 136. (116) ibid, p 140. (117) Bullock, Britain’s Gurkha, p 101. (118) Smith, Brigade of Gurkhas, p 93. (119) Stevens, 4th Indian Division, p 171. (120) ibid, p 174. (121) Interview with Durga Pun, 2/3th Gurkhas. (122) Gould, Imperial soldiers, p 238. (123) Tuker, Gorkha, p 217. (124) Fraser D, And we shall shock them, (Hodder & Stoughton, 1983, London), p 157-158

Change of command was the obvious choice at this time of defeats. Montgomery replaced Auchinleck, and reluctantly he was a critic of the Indian Army. Smith argues, that suspicions about the performance of the Indian Army; undoubtedly existed in the minds of some senior British Army Generals. (125) To which, Gould argument is, Monty’s failure to pass out of Sandhurst high enough to get into the Indian Army had prejudiced

Change of command was the obvious choice at this time of defeats. Montgomery replaced Auchinleck, and reluctantly he was a critic of the Indian Army. Smith argues, that suspicions about the performance of the Indian Army; undoubtedly existed in the minds of some senior British Army Generals. (125) To which, Gould argument is, Monty’s failure to pass out of Sandhurst high enough to get into the Indian Army had prejudiced him against it for life. (126) Certainly not as a result of their performance in Tobruk, but, the Indian Army had not taken any major victories, yet in this war. It was clear that the Indian Army had been underestimated by British generals. Their performance in WW-1 had been somewhat forgotten, at worst the retreat into Burma additionally damaged their reputation. This prejudice exercised by senior British commanders towards the Indian Army prevented the Gurkhas from fighting in the battle of El Alamein; to which, Gen Tuker protested strongly with Gen Montgomery. The resentment expressed by the Indian generals finally counted. The 4th Division had been included in the battle formation, for a final drive to Italy; in which, the Gurkhas of the 1/2 GR and the 1/9th GR were part of it. Parker claims; that North Africa was to be the scene of many Gurkha battles in the campaign that had progressively driven Rommel from one stronghold to another. (127).

him against it for life. (126) Certainly not as a result of their performance in Tobruk, but, the Indian Army had not taken any major victories, yet in this war. It was clear that the Indian Army had been underestimated by British generals. Their performance in WW-1 had been somewhat forgotten, at worst the retreat into Burma additionally damaged their reputation. This prejudice exercised by senior British commanders towards the Indian Army prevented the Gurkhas from fighting in the battle of El Alamein; to which, Gen Tuker protested strongly with Gen Montgomery. The resentment expressed by the Indian generals finally counted. The 4th Division had been included in the battle formation, for a final drive to Italy; in which, the Gurkhas of the 1/2 GR and the 1/9th GR were part of it. Parker claims; that North Africa was to be the scene of many Gurkha battles in the campaign that had progressively driven Rommel from one stronghold to another. (127).

Originally, Montgomery had a plan to launch all force concentrated in a frontal attack, through the coastal gap in the Mareth defense line, where the enemy had a great concentration of force. The Eighth Army’s offensive had been anticipated, by Rommel’s successor Gen Giovanni Messe, just as Montgomery’s original plan proposed. Hamilton claims, neither Gen Francis Tuker nor Gen Douglas Wimberley liked the idea when they reconnoitered the ground. (128) To which; Carver argues, Monty was a master planner of the victory in North Africa however the attack on the Mareth Line, which was not a battle of which Montgomery could be proud. (129) Gould accepts the argument presented by Carver, claiming that Tuker was a master of the moving battle in a more tactical setting in this battle. (130) Aware of the mountainous capabilities of his Indian troops, Tuker suggested a tactically advantageous alternative initial thrust, through the heights of Fatnassa Mountain that would give tactical benefit to the main armored assault against the strong German defense. To this profound confidence, Bullock claims, Gen Tuker knew the mountain warfare capabilities of the men in his division, especially his Gurkha, and he was confident that they could do it. (131) The overall objective for the 4th Division was to take the Fatnassa heights, in a silent night attack, to allow the main assault from the Eighth Army. Gould claims, Tuker, drawing on his experience of the Northwest Frontier, and what he was suggesting was a night attack spearheaded by the Gurkhas on the massif of Fatnassa. (132)

Originally, Montgomery had a plan to launch all force concentrated in a frontal attack, through the coastal gap in the Mareth defense line, where the enemy had a great concentration of force. The Eighth Army’s offensive had been anticipated, by Rommel’s successor Gen Giovanni Messe, just as Montgomery’s original plan proposed. Hamilton claims, neither Gen Francis Tuker nor Gen Douglas Wimberley liked the idea when they reconnoitered the ground. (128) To which; Carver argues, Monty was a master planner of the victory in North Africa however the attack on the Mareth Line, which was not a battle of which Montgomery could be proud. (129) Gould accepts the argument presented by Carver, claiming that Tuker was a master of the moving battle in a more tactical setting in this battle. (130) Aware of the mountainous capabilities of his Indian troops, Tuker suggested a tactically advantageous alternative initial thrust, through the heights of Fatnassa Mountain that would give tactical benefit to the main armored assault against the strong German defense. To this profound confidence, Bullock claims, Gen Tuker knew the mountain warfare capabilities of the men in his division, especially his Gurkha, and he was confident that they could do it. (131) The overall objective for the 4th Division was to take the Fatnassa heights, in a silent night attack, to allow the main assault from the Eighth Army. Gould claims, Tuker, drawing on his experience of the Northwest Frontier, and what he was suggesting was a night attack spearheaded by the Gurkhas on the massif of Fatnassa. (132)

The 1/2nd Gurkhas and the 1/9th Gurkhas were given the leading role, the former was selected to seize the first summit, to create a gap for the next brigade to pass, during the night of Apr 5, 1943. The route was one of the unexpected routes the enemy had anticipated, and extremely difficult to assault through; in Tuker’s words beyond human accomplishment. (133)

In this brave attack, Subedar Lal Bahadur Thapa led his men and fought his way up the narrow gully with no room to maneuver in the fury of machine-gun fire and liberal use of hand grenades by the enemy. (134) Against such overwhelming fire, the Gurkha officer secured the vital entrance, through which, infiltrated the rest of his men from 1/2nd Gurkhas. This brave attack won him a Victoria Cross (VC). Subsequently, the 1/2nd GR secured the vital ground of the enemy and opened a corridor for the 5th Brigade. H Hour, for the main assault of the 8th Army, began after two hours of taking the critical objective. Because of this exploitation, most of the hidden German artillery observation posts on the mountains were eliminated. It relieved the huge intense focus of enemy artillery fire on the main forces, in the coastal plain. The 4th Indian Division’s official history claims, it is scarcely too much to say that the battle of Wadi Akarit had been won singlehanded several hours before the formal attack began. (135)

Finally, ending the war in North Africa, the German Commander of the Afrika Korps and Italian troops surrendered to Lt Col L.C.J Showers of the 1/2nd Gurkhas on May 11, 1943. Smith claims, in this battle, the Gurkhas unwittingly proved their prowess as mountain troops by seizing two of the passes in the Matmata Mountain massif. (136) Stevens supports the claim presented by Smith, that, the high renown of India’s soldiers and the redoubtable Gurkha troops have been enhanced by the outstanding performance of the 4th Indian Division. (137) A victory had been won, a victory that led to increasing interest in the Gurkhas, and on the other hand, overshadowed the critical views, towards the initial failure of the Gurkhas in the First Chindits, in Burma. It was in fact; a turning point, in renewing the reputation of the Indian Army. (138)

Finally, ending the war in North Africa, the German Commander of the Afrika Korps and Italian troops surrendered to Lt Col L.C.J Showers of the 1/2nd Gurkhas on May 11, 1943. Smith claims, in this battle, the Gurkhas unwittingly proved their prowess as mountain troops by seizing two of the passes in the Matmata Mountain massif. (136) Stevens supports the claim presented by Smith, that, the high renown of India’s soldiers and the redoubtable Gurkha troops have been enhanced by the outstanding performance of the 4th Indian Division. (137) A victory had been won, a victory that led to increasing interest in the Gurkhas, and on the other hand, overshadowed the critical views, towards the initial failure of the Gurkhas in the First Chindits, in Burma. It was in fact; a turning point, in renewing the reputation of the Indian Army. (138)

(125) Smith, Brigade of Gurkha, p 94. (126) Gould, Imperial, p 244. (127) Parker, Gurkha, p 125. (128) Hamilton N, Monty; Master of the Battlefield, 1942-1944, (Hodder and Stoughton Ltd, 1985, Sevenoaks), p 215. (129) Carver M, Montgomery, ed. by Keegan J in Churchill’s Generals, (George Weidenfeld and Nicolson Ltd, 1991, New York), p 156. (130) Gould, Imperial, p 245. (131) Bullock, Britain’s, p 108. (132) Gould, Imperial, p 245. (133) Parker, The Gurkhas, p 126. (134) Uprety P.R, Nepal, p 222. (135) Stevens, Fourth Indian, p 223. (136) Smith, the Brigade, p 97. (137) Stevens, Fourth, p 229. (138) Smith, The Brigade, p 99

Press in India, Britain, and America covered the bravery of these once forgotten Imperial Indian soldiers. The war office used the recently victorious 4th Indian Division as war propaganda, to convey a message to the general public, that, this was not only a British war but involved all citizens from the Commonwealth. Importantly, the victory in the Mareth Line and Wadi Akarit, repositioned the Gurkhas, on the list of the generals’ plans again. Many years of soldiering in the Northwest Frontier proved them as skilled mountain soldiers, second to none. The debates on whether Indian soldiers were allowed to fight in Europe, came to a definite conclusion. As a result, the highlander Gurkhas moved to the mountainous terrain of Italy, to recapture Europe. Smith argues that; Conditions in the Italian campaign were more like  those of the Western Front in the Great War than any other theater of operations during WW-2. (139)

those of the Western Front in the Great War than any other theater of operations during WW-2. (139)

After a few months of mountainous mobile warfare training, once again, 1/2 and the 1/9 Gurkhas, as part of the 4th Indian Division, were in a leading role along with the Royal Sussex. The first engagement took place on Feb 18, 1944, to capture Hangman Hill. According to Fraser, the plan was a New Zealand Division would attack Monte Cassino itself from the south-east; the Indians, by now masters of the mountain, would then descend to take the place from the west. (140) In such a difficult mountainous geographical location, the bitter German resistance escalated the risk of attacking troops significantly. Tuker claims, a gallant but costly attempt was made by a Gurkha Battalion to seize by night the German position near the Monastery. (141) The defense position was neatly planned for years and manned by German Paratroopers, intended to hold Allied advance into the heartland of Europe. Additionally, the heavily-bombed ruins of Monte Casino provided excellent cover and concealment for their German occupants. Smith claims, the leading Gurkhas dashed the nearest scrub, only to leap into a death trap. (142) In such a death trap, Fraser asserts, the attacking brigades of the 4th Indian Division were cut to pieces by the deadly close-quarter fire of the defenders. (143) During the first day alone, the leading Gurkha Battalion had one-hundred-and-fifty killed or missing.

This desperate assault to capture the vital position of Monastery Hill inflicted many casualties on the Gurkha units. Reinforcements had a hard time trying to reach such steep terrain, and in the running out of ammunition, troops desperately hide inside the holes of the rocky mountain, against the pounding German artillery and bombs. Realizing the danger, they were in, the Germans attacked the Gurkha positions, and heavy fighting ensued. (144) Gangabahadur claims, running out of ammunition, there was more hand-to-hand fighting using khukuri due to close quarter combat, as both sides competed to gain the ground. (145) The Germans Paratroopers were simply too strong that the 1/9 Gurkhas were reduced to only one-hundred-and-eighty-five men and ordered to withdraw with the Essex and the Rajputanas. However, the second stage of the attack was renewed again on Mar 5. This time, after nearly six weeks of continuous fighting, the 9th Gurkha won renown clinging to the aptly named Hangman’s Hill on the slopes of Monte Cassino under withering fire, however, the price was too high, for such a small piece of land. (146)

This desperate assault to capture the vital position of Monastery Hill inflicted many casualties on the Gurkha units. Reinforcements had a hard time trying to reach such steep terrain, and in the running out of ammunition, troops desperately hide inside the holes of the rocky mountain, against the pounding German artillery and bombs. Realizing the danger, they were in, the Germans attacked the Gurkha positions, and heavy fighting ensued. (144) Gangabahadur claims, running out of ammunition, there was more hand-to-hand fighting using khukuri due to close quarter combat, as both sides competed to gain the ground. (145) The Germans Paratroopers were simply too strong that the 1/9 Gurkhas were reduced to only one-hundred-and-eighty-five men and ordered to withdraw with the Essex and the Rajputanas. However, the second stage of the attack was renewed again on Mar 5. This time, after nearly six weeks of continuous fighting, the 9th Gurkha won renown clinging to the aptly named Hangman’s Hill on the slopes of Monte Cassino under withering fire, however, the price was too high, for such a small piece of land. (146)

The withdrawing German forces once again formed a strong defense along the Gothic Line. Bullock claims, again, breaking into the Gothic Line proved to be a long and bloody undertaking in which all nine Gurkha battalions in Italy were involved. (147) The 43rd Gurkha Lorried Brigade as infantry was primarily involved in the major battles. Since 1942, the brigade consisting of the 6th, then 8th, and the 10th Gurkha Rifles, maintained the policy of containment, against the pro-German force in the Middle East, and remained there without fighting any major battles, but these units continued to train for mobile warfare for the mountainous battles ahead.

On Oct 6, 1944, the 43rd Brigade transferring into the 10th Division was ordered on a night attack uphill in Monte Chico, 1300 feet high from the sea level. Marston claims, the fighting in northern Italy was similar to earlier campaigns-countless river crossings; the taking of hills, mountains, and fortified villages. (148) The defender used their overwhelming firepower to inflict maximum damage to advancing troops. Use of artillery extensively, was one of the prime reasons for inflicting heavy casualties in the Gurkha battalion. (149) The enemy opposition was significantly stiff, and the approaches were comparatively complex. Lunt claims that the Germans were relying on the difficulties of the approach, and were taken by surprise. (150) In most cases, Gurkhas using their khukuri at the close quarter battle, in which they always excelled, added to the old fear of such a weapon used by such warriors, against their enemies.

On Oct 6, 1944, the 43rd Brigade transferring into the 10th Division was ordered on a night attack uphill in Monte Chico, 1300 feet high from the sea level. Marston claims, the fighting in northern Italy was similar to earlier campaigns-countless river crossings; the taking of hills, mountains, and fortified villages. (148) The defender used their overwhelming firepower to inflict maximum damage to advancing troops. Use of artillery extensively, was one of the prime reasons for inflicting heavy casualties in the Gurkha battalion. (149) The enemy opposition was significantly stiff, and the approaches were comparatively complex. Lunt claims that the Germans were relying on the difficulties of the approach, and were taken by surprise. (150) In most cases, Gurkhas using their khukuri at the close quarter battle, in which they always excelled, added to the old fear of such a weapon used by such warriors, against their enemies.

Witnessing his comrade’s head chopped off, was not an easy experience for a German. A Gurkha claims; that Germans used to show a picture of their family in such a situation, to save themselves as a POW. (151) However, in such mountainous terrains, the single random act of bravery was most important when the advancing troops were pinned down by a single German machine-gun post. In such circumstances, Rifleman Sherbahadur Gurung took charge of a Bren gun and cleared a strong German defensive position. This act won him the Victoria Cross, but importantly, his company was able to successfully attack an objective Point 366, because of his single act of bravery.

Despite the previous mountainous operations, North Italy was relatively flat. The tanks and infantry combined tactics were seen to be more effective. On top of that, moving from one town of a stronghold to another ensured heavy urban fighting. In such conditions, the battle for Medicina along with the 14/20 King’s Hussars in Apr 1945, was the last battle the Gurkhas fought in Italy. Tanks were heavily used in this street-to-street battle. Despite the successful attacks by Gurkha units, few men lost their lives unnecessarily, in what is now termed as a Blue on Blue situation.

Despite the previous mountainous operations, North Italy was relatively flat. The tanks and infantry combined tactics were seen to be more effective. On top of that, moving from one town of a stronghold to another ensured heavy urban fighting. In such conditions, the battle for Medicina along with the 14/20 King’s Hussars in Apr 1945, was the last battle the Gurkhas fought in Italy. Tanks were heavily used in this street-to-street battle. Despite the successful attacks by Gurkha units, few men lost their lives unnecessarily, in what is now termed as a Blue on Blue situation.

The 6th Gurkhas war diary claims that one man has been overrun and killed by a Kangaroo. One man was crushed to death under a Kangaroo (tank) which overturned. (152) In such complex urban fighting, the chaos of battle was rife, even methodical; thoughtful fighting men can be affected by sudden panic. Nevertheless, victory over the Axis forces had been won in Italy. Despite the Gurkhas’ long and successful campaigns in the Middle East, the Gurkhas’ major fighting only started to take place during the Second Battle of El Alamein; in which, they demonstrated their prowess as mountainous soldiers. Many years of soldiering in the Northwest Frontiers served as the training ground for this kind of mountain warfare.

The victory of the Mareth Line was a turning point in the reputation of the Indian Army, in that it overshadowed the humiliating defeats of Burma, and importantly, swayed senior commanders on the fighting capacity of the Gurkhas. However, the lessons learned from the desert could not be effective in the jungles of Burma, as the nature of warfare varied tremendously.

(139) Ibid, p 100. (140) Fraser, And we shall, p 285. (141) Tuker, Gorkha, p 227. (142) Smith, The Brigade, p 102-103. (143) Fraser, And we shall, p 285. (144) Marston, A force transformed, in a history of India and South Asia, p 115. (145) Cross and Gurung, Battle account of Gangabahadur Thapa, IDSM, 1/9th Gurkhas, in Gurkhas at War, p 135. (146) Gould, Imperial, p 250. (147) Bullock, Britain’s, p 121. (148) Marston, A force transformed, in a history of India and South Asia, p 116. (149) Interview with Gurkha Officer, Army No. 16216, 2/10th Gurkhas. (150) Lunt, Jai, p 78. (151) Interview with Gurkha Officer, Army No. 16216, 2/10th Gurkhas. (152) 6th Gurkha Rifles’ war diary.

(139) Ibid, p 100. (140) Fraser, And we shall, p 285. (141) Tuker, Gorkha, p 227. (142) Smith, The Brigade, p 102-103. (143) Fraser, And we shall, p 285. (144) Marston, A force transformed, in a history of India and South Asia, p 115. (145) Cross and Gurung, Battle account of Gangabahadur Thapa, IDSM, 1/9th Gurkhas, in Gurkhas at War, p 135. (146) Gould, Imperial, p 250. (147) Bullock, Britain’s, p 121. (148) Marston, A force transformed, in a history of India and South Asia, p 116. (149) Interview with Gurkha Officer, Army No. 16216, 2/10th Gurkhas. (150) Lunt, Jai, p 78. (151) Interview with Gurkha Officer, Army No. 16216, 2/10th Gurkhas. (152) 6th Gurkha Rifles’ war diary.