The Battle of Montélimar

The 36-ID consolidated and held positions north of Montélimar, repulsing attack after attack. until Aug 26, when the Germans succeeded in breaking the Division roadblock on the east bank road. This happened to be the weakest point in the Division’s defensive perimeter, and the German breakthrough at this location was probably due to their knowledge of dispositions obtained from the captured order.

The 36-ID consolidated and held positions north of Montélimar, repulsing attack after attack. until Aug 26, when the Germans succeeded in breaking the Division roadblock on the east bank road. This happened to be the weakest point in the Division’s defensive perimeter, and the German breakthrough at this location was probably due to their knowledge of dispositions obtained from the captured order.

The Germans attacked continuously and hit everywhere in a desperate attempt to extricate their trapped forces.

The Germans attacked continuously and hit everywhere in a desperate attempt to extricate their trapped forces.  By Aug 27, the 3-ID was attacking northwest to clear the enemy out of the Orange, Nyons, Montélimar triangle and was encountering strong enemy delaying actions. Near Montélimar, the heaviest German motor movements yet reported, a large column of tanks, armored vehicles, self-propelled guns, and half-tracks, was observed filtering northward. The 36-ID, although in an ideal spot for interception was unable to break loose from its own fight, and could not keep the enemy from filtering through.

By Aug 27, the 3-ID was attacking northwest to clear the enemy out of the Orange, Nyons, Montélimar triangle and was encountering strong enemy delaying actions. Near Montélimar, the heaviest German motor movements yet reported, a large column of tanks, armored vehicles, self-propelled guns, and half-tracks, was observed filtering northward. The 36-ID, although in an ideal spot for interception was unable to break loose from its own fight, and could not keep the enemy from filtering through.

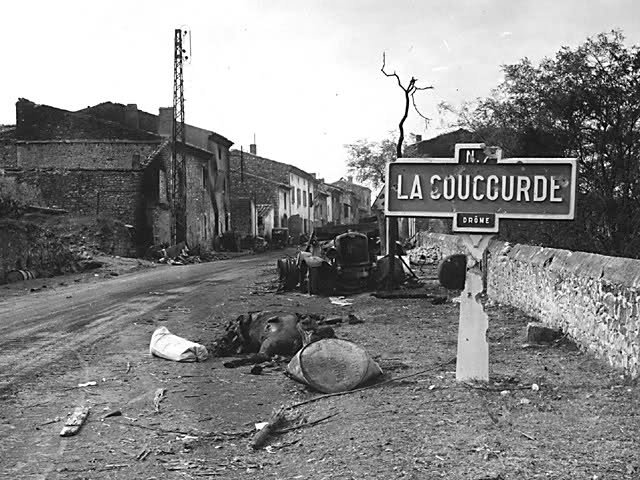

Enemy prisoners reported that as of Aug 27, the bulk of the 11.Panzer-Division had succeeded in passing through, but the 198.Infantry-Division was still trapped south of Montélimar. On this same day, the 3-ID broke through the delaying line against heavy opposition and captured a 2000 Meters long double column of German vehicles moving toward Montélimar. They continued their attack on the 28, striking Montélimar from the south, west, and north, and by noon, on the 29, they occupied the city and all resistance east and south of Montélimar had ceased. On the morning of Aug 29, the Germans strongly attacked north of Montélimar in an effort to break out with the remainder of the 198.Infantry-Division. The 3-ID repulsed the attack and captured the 198.Infantry-Division’s Commander, as well as vast stockpiles of abandoned equipment; yet many of the personnel in the trapped unit succeeded in escaping. The tactical situation now demanded that efforts be made to halt the enemy before he could complete crossing of the Drôme River further north. Operations along the Drôme River represented the final phase of the Battle of Montélimar. This river was the last barrier in the German retreat northward to Lyon. The 36-ID repositioned its forces, and by Aug 27, they had narrowed German escape routes to one. Air support and artillery harassed enemy traffic and destroyed bridges, but the Drôme was fordable at most points during the month of August, so some forces still escaped. Overall, allied forces inflicted heavy losses on the German Army at Montélimar.

They destroyed 4000 vehicles, tanks, and guns, as well as 2000 horses and 6 railway guns. By Aug 28, over 42.000 prisoners were taken. Only a small fraction of the German 19.Army was able to run the gauntlet at Montélimar and escape with their equipment, and no division, except the 11.Panzer-Division, escaped as an intact unit. The reasons for the success at Montélimar and the Dragoon Operation, in general, were basic and included: (1) – the use of battle-experienced commanders and troops; (2) – experienced planning staffs, most of whom had worked together in other Mediterranean operations; (3) – overwhelming air superiority; (4) – excellent Allied intelligence, in contrast to poor and inadequate intelligence on the German side; (5) – inherent weakness of enemy forces characterized by their lack of mobility, low morale, and low state of combat efficiency; (6) – the early breakdown of German communication, command, and control and (7), – aggressive exploitation by troops of the US VI Corps.

The Situation at the Close of the Battle

At the end of August, the 7-A had completed the liberation of southern France and was closing in on the city of Lyon. On the eastern flank, patrols of the 1st Airborne Task Force reached the Italian Border. In the north, the 36 and 45-IDs had already crossed the Rhone River where it flows into Lyon from the high Alps to the east and were operating northeast of the city.

The 3-ID, after mopping up the Montélimar battle area, went into a reserve role near Voiron. On the west bank of the Rhone, below Lyon, units of the French Army were pushing the enemy northward, and French Reconnaissance elements were advancing along the Mediterranean Coast close to the Spanish Border. This marked the end of Operation Dragoon. From here on, the plan was to pursue the remainder of the German 19.Army, pushing it completely out of France, and to make contact with Gen Patton’s American Third Army.

Significance of the Action

Immediate

There is no doubt about the tactical decisiveness of Operation Anvil/Dragoon. Enemy resistance was so slight as to permit immediate exploitation northward, through Grenoble towards Lyons, allowing a link-up with the US 3-A 28 days after the landing. The operation created a diversionary effect to assist Overlord, protected the right flank of the 3-A, and provided another major port on the continent. However, the rapid progress toward the north was so unexpected that plans had not been made for that eventuality. For example, the AAF P-47’s operating out of Corsica had range difficulties by D+5. Fighter bombers were unable to operate at all in the northern sector near Grenoble. Logistics was supported from the assault beaches until mid-September when Marseilles and Toulon were seized. This created a supply line of 280 KM, one way.

Consequently, although allied forces took advantage of the opportunities presented, they were unable to capitalize fully on them. The immediate effect of the battle’s outcome on allied forces was the ejection of German forces from southern France; the interjection of the Free French Forces into the fighting with a corresponding enhancement of the political situation among the allies; the availability to the allies of two major port complexes (Marseilles and Toulon); the benefit deriving from two fronts in France, and the morale enhancing factor of a truly successful major operation. As far as the Germans were concerned, the impact of the operation was severe. The seven German divisions opposing the invasion were eliminated as fighting units. Most Axis troops in southwestern France were surrounded and Germany was forced to divert its attention from Normandy</b<.

The battle provided a significant disadvantage for the Germans. As Allan Wilt states in his book ‘The French Riviera Campaign of August 1944’, No matter how depleted the Axis forces were, the Germans still had to keep considerable numbers of formations positioned along France’s Mediterranean Coast. In this sense, particularly after August 7, when the Germans knew that the allies were definitively building up their forces for an attack, Dragoon did restrain the Wehrmacht from sending additional men and material north. This, a threat alone would not have been accomplished. Also, the inescapable fact remains that 79.000 prisoners were taken during the operation at a time when Germany could least afford it. In addition, the seizing, of Toulon and Marseilles precluded, almost completely, the use of enemy ships and aircraft in the western Mediterranean.

Long Term

There is some disagreement as to whether the outcome of the battle affected the long-term objectives of the allies. Churchill believed the Mediterranean invasion was unnecessary so far as it related to supporting the Normandy landings, and he believed the forces could be better used to support the allied effort in Italy, or even an invasion of the Balkans. Chester Wilmot, an Australian historian, believed that Operation Anvil/Dragoon distorted allied strategy in the Mediterranean and the west, to the immediate benefit of Hitler and the ultimate advantage of Stalin. The battle did not place the German Army in a position from which it could not recover, in the sense that they would have been ultimately defeated with or without a Mediterranean invasion. Such an outcome was simply a matter of time after the Normandy breakout. By virtue of the same reasoning, the battle did not decide the outcome of the war. One can say that the outcome was the war in Europe was decided when Operation Overlord was approved for execution. The battle ranks in importance with the allied landings in Sicily, which were also a spectacular tactical success, but did not decide the outcome of the Italian Campaign.