Document Source: Operations of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, Royal Canadian Army, in Belgium, Holland, and Germany, 1944-1945. The Final Operation: January 2, 1945, to March 24, 1945.

(1) The object of this report is to describe the part played by the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, Canadian Infantry Corps, in the operations of the Allied Armies in northwest Europa during the final phase of WW-2. The report will deal with a minor extent with the role of the unit as ground troop helping to hold the front line in Belgium, during the Ardennes counteroffensive, and in the Netherlands, during the Battle of the Rhineland. It will relate in greater detail the story of the Battalion parachuting east of the Rhine River on March 24, 1945, and subsequently fighting overland to meet the Red Army on May 2, at the Baltic Port of Wismar. First among the troops of the British 21st Army Group to join hands with the Russians, no other unit of the Canadian Army penetrated so deeply into Germany nor progressed so far eastward in that theater of operations.

(1) The object of this report is to describe the part played by the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, Canadian Infantry Corps, in the operations of the Allied Armies in northwest Europa during the final phase of WW-2. The report will deal with a minor extent with the role of the unit as ground troop helping to hold the front line in Belgium, during the Ardennes counteroffensive, and in the Netherlands, during the Battle of the Rhineland. It will relate in greater detail the story of the Battalion parachuting east of the Rhine River on March 24, 1945, and subsequently fighting overland to meet the Red Army on May 2, at the Baltic Port of Wismar. First among the troops of the British 21st Army Group to join hands with the Russians, no other unit of the Canadian Army penetrated so deeply into Germany nor progressed so far eastward in that theater of operations.

(2) This report supplements two reports produced by the Historical Officer, Canadian Military HQs. Report No 138 discusses the formation of the 1-CPB in Jul 1942, and its initial training in the USA, Canada, and England. Report No 139, deals exclusively with its participation in the allied invasion across the Channel as part of the airborne armada which descended upon Normandy that memorable morning of June 6, 1944, and thereafter fought as front-line troops during the summer campaign to expel the Germans from France. This third report is intended to conclude the series. It begins with a brief introductory account telling of further training undertaken in England upon the return of the Battalion from France on September 6, 1944. The main story of final operations is followed by a short account of the repatriation of the unit and its disbandment in Canada on September 30, 1945. The report concludes with a summary of the battle casualties suffered and the decorations awarded.

(3) The first two reports were completed by July 7, 1946, at the Canadian Military HQs in London, whereas this concluding report has been written a year later at the Army HQs in Ottawa. Copies of the unit War Diary including original operational maps have been available, however, and have provided the chief source of information. The story of the parachute descent has been checked against a comprehensive report by American observers entitled Operation Varsity, the Airborne Crossing of the Rhine River, March 1945. Statements outlining higher strategy have been drawn largely from the published report of the Supreme Commander to the Combined Chief of Staff. Much use has also been made of the well-known books written by FM Montgomery, Commander-in-Chief of the UK 21-AG, and by Lt Gen Lewis H. Brereton, Commanding the 1-A/B-AA.

(3) The first two reports were completed by July 7, 1946, at the Canadian Military HQs in London, whereas this concluding report has been written a year later at the Army HQs in Ottawa. Copies of the unit War Diary including original operational maps have been available, however, and have provided the chief source of information. The story of the parachute descent has been checked against a comprehensive report by American observers entitled Operation Varsity, the Airborne Crossing of the Rhine River, March 1945. Statements outlining higher strategy have been drawn largely from the published report of the Supreme Commander to the Combined Chief of Staff. Much use has also been made of the well-known books written by FM Montgomery, Commander-in-Chief of the UK 21-AG, and by Lt Gen Lewis H. Brereton, Commanding the 1-A/B-AA.

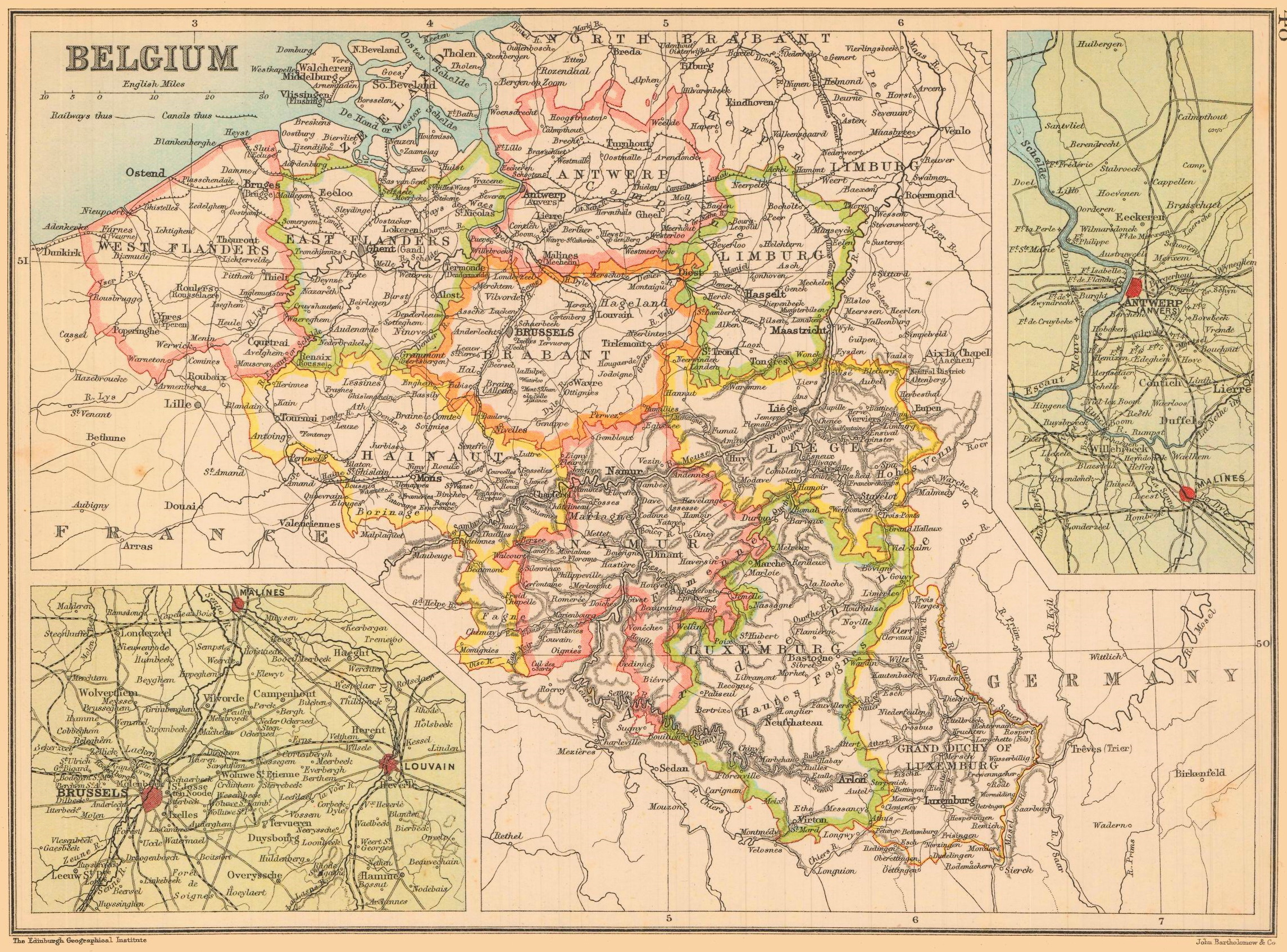

(4) Map references throughout the report refer to the following G.S.G.S. maps: England & Wales, 1:63,360, sheet 107; Belgium & Northeast France, 1:100,000, sheets 4 and 13; Germany, 1:50,000, sheets 16 and 36 and Central Europe, 1:100,000, sheets K5, K6, L5, L6, M5, N2, N3, N4, P1, P2, and Q1

(5) The 1-CPB returned to England from France on September 6/7, 1944, at the time when the Allied Armies were sweeping into Belgium and the Germans were still in full rout from Falaise. The Battalion had received its baptism of fire by dropping from the skies upon Normandy between 0100 and 0130 on D-day. On that day alone the unit had suffered 117 casualties, and in three months of fighting that summer, its battle losses totaled 24 officers and 343 other ranks. Reinforcements had not been sufficient in the later stages to maintain the Battalion War Establishment of 31 officers and 587 other ranks; consequently, there were deficiencies of 5 officers and 242 other ranks when the unit returned to England. Their internal reorganization was to be undertaken and hopes were high that further airborne operations were in prospect.

(6) The 1-CPB had trained and fought as the only Canadian element basically part of the 6th British Airborne Division, retaining this status when the entire Division was withdrawn from operations and returning to the United Kingdom with it. The Canadians remained brigaded with the 8th and 9th Parachute Battalions to form the 3rd Parachute Brigade, commanded by Brig S.J.L. Hill, D.S.O., M.C. Just prior to this move from the Continent the Battalion’s first Commanding Officer, Lt Col G.F.P. Bradbrooke, received a staff appointment and Maj G.F. Eadie assumed the temporary command. Back in England, Maj J.A. Nicklin rejoined the unit on being appointed to command effective September 8, 1944, with the rank of Lt Col. The new CO an outstanding athlete, had established a reputation across Canada as a former rugby star of the Winnipeg Blue Bombers. One of the original officers of the Battalion, he had parachuted with it into France on D-day as second-in-command but later had been evacuated (June 23) with multiple wounds. Maj Eadie now became second-in-command, with Maj C.E. Fuller, Maj P.R. Griffin (MC), Maj J.D. Hanson (MC), and Maj R. Hilborn as Company COs.

(7) Once re-established in their old quarters at Carter Barracks, Bulford, Wiltshire, all personnel were given 12 days leave ending September 4, 1944. General training then began in earnest, with the battalion restored to full strength by reinforcements from the 1st Canadian Parachute Training Company. During the month of October 1944, each of the three rifle companies was sent in turn to street fighting courses at Southampton and in the Battersea area of London, while the training company attended a similar course at Birmingham.

(8) On October 9/10, the entire Battalion participated in a 3rd Paratrooper Brigade scheme termed Exercise Fog, whose objects were (a) Detail practice for a large-scale drop on a Brigade DZ; (b) Practice movement by night; (c) Practice of evacuation of casualties. The operation order for the exercise stated that the 3rd Paratrooper Brigade will seize and hold Shrewton – a main center of communication, and detailed the following tasks to the 1-CPB and (a) make contact with Glider Elements and conduct them to the Brigade Objective; (b) seize and hold feature East of Shrewton; (c) prevent Enemy movement south. Poor visibility caused a 24-hour delay, but at 1645, on October 9, 1944, the Battalion em-planed at Walford, Northampton, in aircraft of the 9th Troop Carrying Command (USAAF).

The unit diarist records the takeoff was at 1700. Aircraft were over the DZ in tight formation in 1849. Personnel dropped and every man was clear of the DZ in 20 minutes – the maximum laid down by the Brigade Commander. Personnel made their way to the rendezvous and then marched cross-country to Shrewton which was the objective. The rendezvous area was cleared in 2020, and the objective was reached at about 2335. Small parties of the enemy were encountered and dealt with successfully on the way to the objective and upon arrival there, the Battalion took up defensive positions and dug in. The 1-CPB Training Company took part in the role of the enemy, jumping from Stirlings, but unfortunately, the jump was made with 8 non-fatal casualties caused by a plane flying at 150′ while dropping men. The scheme ended the following morning and a 0230 route march brought the troops back to the barracks, where officers and men began a thorough study of the tactics employed. Baker Co, had a follow-up exercise of its own two days later in which men were dropped from trucks by pairs every 100 yards and ordered to move to the rendezvous, advancing from there towards the objective. This was the village of Cholderton, with the way barred by an enemy platoon provided by Charlie Co, but the assaulting troops won through in a mock battle lasting 18 minutes.

(9) Although these courses and exercises served to enliven routine training, the men were for a time in a very unsettled state, perhaps due to sudden release from the tension of the summer months fighting. The following entries in the unit War Diary are evidence of this unusual attitude. October 20, 1944, on the evening supper parade great confusion was caused when the men refused to eat. The complaint lay not in the food but in the treatment of the men by the Commanding Officer. October 21, 1944, general training during the day. Personnel still not eating. Platoon Commanders spoke to platoons to ascertain complaints and in the afternoon changes in orders heretofore laid down were made but only 60 men ate supper. October 22, 1944, personnel still in camp refused to eat again today. On October 23, 1944, approximately 60 men ate their breakfast. General training in the morning and a lecture from Brigadier Hill who promised there would be an investigation into all grievances. Personnel all ate dinner and supper.

Personnel of the 1st Canadian Parachute Training Company also took part in the hunger strike, advancing numerous grievances the chief of which were concerned with dress regulations both around camp and walking out. Refusal to eat was the only sign of dissatisfaction, and no further trouble was encountered after the Brigadier’s investigation. All grievances were brought forward at the Brigade Commander’s inspection on November 16, 1944, but no drastic action was necessary and training activities soon absorbed the attention of all ranks.

(10) During the month of November the short courses on street fighting were concluded and emphasis shifted to weapon training, Rifle, Sten Gun, Bren, Vickers MG, PIAT (Projectile Infantry Antitank), Mortar, Hand Grenade, Bangalore Torpedoes, Mines and Booby Traps (our own and enemy). The Mortar Platoon continued training with the 3″ mortar but stressed drills with the American 60-MM mortar, giving several demonstrations in handling this weapon. The Vickers, the PIAT, and the Signal Platoons were also busy in their specialized fields, the Intelligence Section held a two-day exercise of their own prepared by the Intelligence Officer, and the rifle companies made a considerable amount of range work. Route marches increased from 10 to 20 miles and long-distance runs from 2 to 3 miles. Recreation included films, concerts, tabloid sports, and a 36-hour pass for all personnel on November 11/12, with a special train to London.

(11) The main training feature of November was Exercise Eve, a 6th British Airborne Division scheme in which the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion as a whole and the Intelligence Section of 1st Canadian Parachute Training Company participated. Personnel traveled by lorry a day’s journey to the transit camp, where bad weather once again caused a 24-hour delay. The exercise finally took place on November 21 and included a daylight parachute jump followed by an assault on the enemy positions with preparations for counterattacks. Rehearsals such as Exercises Gog and Eve doubtless raised hopes that airborne operations would soon follow and served as some measure of compensation for the exclusion of the Division from the descent on Arnhem in September 1944.

(11) The main training feature of November was Exercise Eve, a 6th British Airborne Division scheme in which the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion as a whole and the Intelligence Section of 1st Canadian Parachute Training Company participated. Personnel traveled by lorry a day’s journey to the transit camp, where bad weather once again caused a 24-hour delay. The exercise finally took place on November 21 and included a daylight parachute jump followed by an assault on the enemy positions with preparations for counterattacks. Rehearsals such as Exercises Gog and Eve doubtless raised hopes that airborne operations would soon follow and served as some measure of compensation for the exclusion of the Division from the descent on Arnhem in September 1944.

(12) From December 1 to December 10, the personnel of the Battalion and the Training Company were on privilege leave, extended 24 hours in certain instances by the G.O.C as a reward for the cleanliness of barracks. During the month three drafts totaling 3 officers and 256 other ranks arrived from Canada to join the Training Co, whose strength at the beginning of the new year stood at 694 all ranks. It was possible now to maintain the Battalion at full strength, vacancies as they occurred being filled with qualified jumpers. Extensive range practice with all types of weapons on establishment kept officers and men fully occupied and keen for action.

(12) From December 1 to December 10, the personnel of the Battalion and the Training Company were on privilege leave, extended 24 hours in certain instances by the G.O.C as a reward for the cleanliness of barracks. During the month three drafts totaling 3 officers and 256 other ranks arrived from Canada to join the Training Co, whose strength at the beginning of the new year stood at 694 all ranks. It was possible now to maintain the Battalion at full strength, vacancies as they occurred being filled with qualified jumpers. Extensive range practice with all types of weapons on establishment kept officers and men fully occupied and keen for action.

(13) Finally, on December 20, the Commanding Officer warned all ranks that the 1-CPB was returning overseas for active duty. The advance party left that day and the unit was placed on six hours’ notice, continuing in that state for more than three days. A Christmas dinner was served in Carter Barracks on December 22, and another in the transit camp on December 25. On Christmas Eve the Battalion proceeded by train to Folkestone, embarking there on the SS Canterbury at 1830 on Christmas Day for Ostende, Belgium. Crossing the English Channel by boat must have been a bitter disappointment to trained paratroopers, but at least they were getting back into a fighting role.

(14)The return of the 6-A/B (UK) to the Continent at this stage of the war was part of a mass movement of troops urgently required to help stem the Ardennes counter-offensive launched by the Germans on December 16, against Gen Omar N. Bradley’s 12-AG. The enemy’s general plan was to break through the thin line of defenses in a sudden blitz drive to the Meuse River in the Liège-Namur area of Belgium and continue on to Antwerp in order to seize or destroy this great port of supply and split the Allied Armies. Assembling all available reserves of armor and infantry to meet the threat, Gen Eisenhower decided to make extensive use of troops from airborne formations.

(14)The return of the 6-A/B (UK) to the Continent at this stage of the war was part of a mass movement of troops urgently required to help stem the Ardennes counter-offensive launched by the Germans on December 16, against Gen Omar N. Bradley’s 12-AG. The enemy’s general plan was to break through the thin line of defenses in a sudden blitz drive to the Meuse River in the Liège-Namur area of Belgium and continue on to Antwerp in order to seize or destroy this great port of supply and split the Allied Armies. Assembling all available reserves of armor and infantry to meet the threat, Gen Eisenhower decided to make extensive use of troops from airborne formations.

Reinforcements had to be rushed to the Ardennes. The Supreme Commander immediately called upon the 82-A/B and the 101-A/B, which had been through a bitter campaign in Holland and were being refitted and reequipped in the Reims area (France) for future airborne operations. Farthest from their minds was a commitment to return to action. The Supreme Commander directed that the movement by Air of the 17-A/B begin as soon as weather permits. He also directed that the British 6-A/B (UK) be moved to the Continent by water with first priority.

Reinforcements had to be rushed to the Ardennes. The Supreme Commander immediately called upon the 82-A/B and the 101-A/B, which had been through a bitter campaign in Holland and were being refitted and reequipped in the Reims area (France) for future airborne operations. Farthest from their minds was a commitment to return to action. The Supreme Commander directed that the movement by Air of the 17-A/B begin as soon as weather permits. He also directed that the British 6-A/B (UK) be moved to the Continent by water with first priority.