The Doolittle Raid of Apr 18, 1942, was the first air raid by the USA to strike the Japanese home islands during WW-2. The mission was notable in that it was the only operation in which USAAF bombers were launched from a US Navy aircraft carrier. It was the longest combat mission ever flown by the B-25 Mitchell medium bomber. This raid had its start in a desire by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, expressed to the Joint Chiefs of Staff in a meeting at the White House on Dec 21, 1941, that Japan be bombed as soon as possible to boost public morale after the disaster at Pearl Harbor.

The Doolittle Raid of Apr 18, 1942, was the first air raid by the USA to strike the Japanese home islands during WW-2. The mission was notable in that it was the only operation in which USAAF bombers were launched from a US Navy aircraft carrier. It was the longest combat mission ever flown by the B-25 Mitchell medium bomber. This raid had its start in a desire by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, expressed to the Joint Chiefs of Staff in a meeting at the White House on Dec 21, 1941, that Japan be bombed as soon as possible to boost public morale after the disaster at Pearl Harbor.

The Japanese people had been told they were invulnerable. An attack on the Japanese homeland would cause confusion in the minds of the Japanese people and sow doubt about the reliability of their leaders. There was a second, and equally important, psychological reason for this attack. Americans badly needed a morale boost. Doolittle, later in his autobiography, recounted that the raid was intended to bolster American morale and to cause the Japanese to begin doubting their leadership, in which it succeeded.

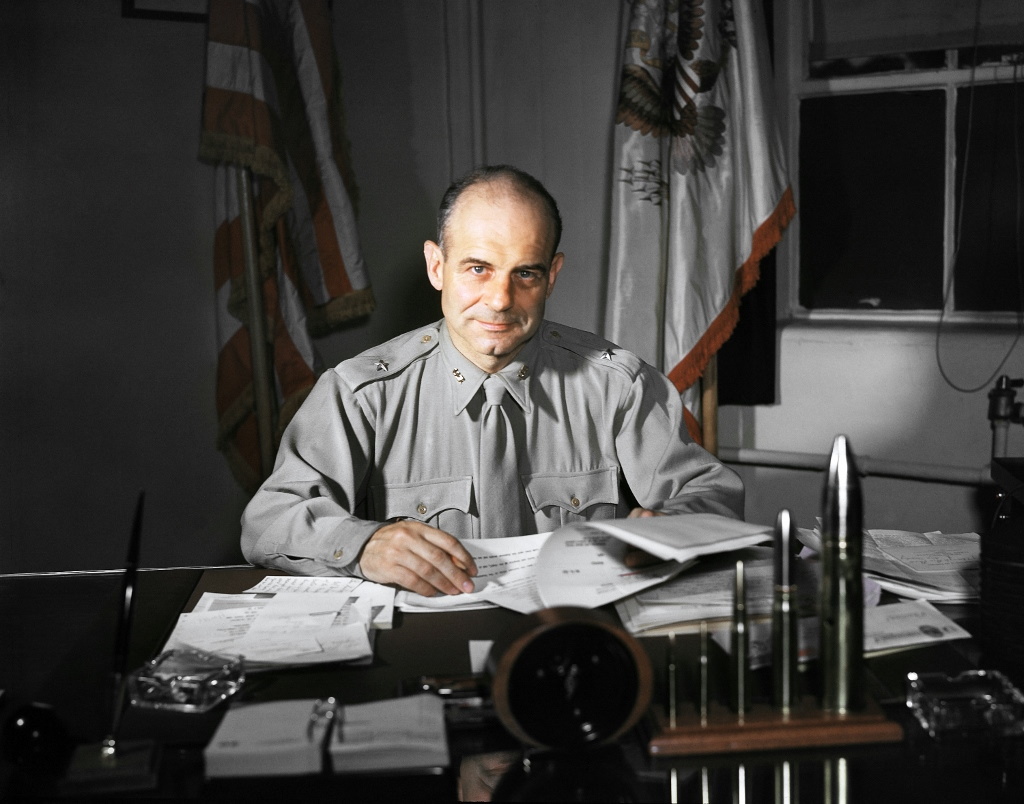

The concept for the attack came from Navy Capt Francis S. Low, Assistant Chief of Staff for the anti-submarine warfare who reported to Adm Ernest J. King on Jan 10, 1942, that he thought twin-engine Army bombers could be launched from an aircraft carrier, after observing several at a naval airfield in Norfolk, Virginia, where the runway was painted with the outline of a carrier deck for landing practice. The attack was planned and led by Lt Col James Doolittle, a famous civilian aviator and aeronautical engineer before the war.

The requirements to accomplish this operation requested that the aircraft had to have a cruising range of 2400 nautical miles (4400 km) with a 2000-pound (910 Kg) bomb load, resulted in the selection of the B-25-B Mitchell to carry out the task. The Martin B-26 Marauder, the Douglas B-18 Bolo, and the Douglas B-23 Dragon were also considered, but the B-26 had questionable takeoff characteristics from a carrier deck and the B-23’s wingspan was nearly 50% greater than the B-25’s, reducing the number of the plane that could be taken aboard a carrier and posing risks to the ship’s island (superstructure). The B-18, one of the final two types considered by Doolittle, was rejected for the same reason.

The requirements to accomplish this operation requested that the aircraft had to have a cruising range of 2400 nautical miles (4400 km) with a 2000-pound (910 Kg) bomb load, resulted in the selection of the B-25-B Mitchell to carry out the task. The Martin B-26 Marauder, the Douglas B-18 Bolo, and the Douglas B-23 Dragon were also considered, but the B-26 had questionable takeoff characteristics from a carrier deck and the B-23’s wingspan was nearly 50% greater than the B-25’s, reducing the number of the plane that could be taken aboard a carrier and posing risks to the ship’s island (superstructure). The B-18, one of the final two types considered by Doolittle, was rejected for the same reason.

In 1942, the B-25 had still to be tested in combat, but subsequent tests indicated they could fulfill the mission’s requirements. Doolittle’s first report on the plan suggested the bombers might land in Vladivostok, USSR, shortening the flight by 600 nautical miles (1100 Km) on the basis of turning over the B-25s as Lend-Lease. Negotiations with the Soviet Union, which had signed a neutrality pact with Japan in April 1941, for permission were fruitless. Something else was also pointed out: bombers attacking defended targets often relied on a fighter escort to defend them from enemy fighters; not only did Doolittle’s aircraft lack a full complement of guns to save weight, but it was not possible for fighters to accompany them.

When planning indicated that the B-25 was the aircraft best meeting all specifications of the mission, two were loaded aboard the aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8) at Norfolk, Virginia, and flown off the deck without difficulty on Feb 3, 1942. The raid was approved and the 17th Bomb Group (Medium), the first Medium Bomb Group with 4 Squadrons using B-25s in the AAF, was chosen to provide the pool of crews from which volunteers would be recruited. Based in Pendleton, Oregon, the Group was moved to Lexington County Army Air Base at Columbia, South Carolina, to fly similar patrols off the East Coast of the US and prepare for the mission against Japan.

When planning indicated that the B-25 was the aircraft best meeting all specifications of the mission, two were loaded aboard the aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8) at Norfolk, Virginia, and flown off the deck without difficulty on Feb 3, 1942. The raid was approved and the 17th Bomb Group (Medium), the first Medium Bomb Group with 4 Squadrons using B-25s in the AAF, was chosen to provide the pool of crews from which volunteers would be recruited. Based in Pendleton, Oregon, the Group was moved to Lexington County Army Air Base at Columbia, South Carolina, to fly similar patrols off the East Coast of the US and prepare for the mission against Japan.

Initial planning called for 20 aircraft, 24 of the group’s B-25-B Mitchell were diverted to the Mid-Continent Airlines modification center in Minneapolis, Minnesota which became the first modification center operational. From nearby Fort Snelling, the 710-MP Bn provided tight security around this hangar as well as the entire Base.

The airplanes had to be modified. These modifications were the removal of the lower gun turret; the installation of De-icers and Anti-icers; steel blast plates mounted on the fuselage around the upper turret; the removal of the liaison radio set (a weight impediment); the installation of a 160-gallon collapsible neoprene auxiliary fuel tank fixed to the top of the bomb bay, and support mounts for additional fuel cells in the bomb bay, crawl-way and lower turret area to increase fuel capacity from 646 to 1141 gallons; installation of mock gun barrels installed in the tail cone; the replacement of their Norden bomb-sight with a makeshift aiming sight devised by pilot Capt Charles Ross Greening and called the Mark Twain. Note that two bombers also had cameras mounted to record the results of the bombing. The 24 crews selected picked up the modified bombers in Minneapolis and flew them to Eglin Field, Florida, beginning Mar 1, 1942. There the crews received intensive training for three weeks in simulated carrier deck takeoffs, low-level and night flying, low-altitude bombing, and over-water navigation, primarily out of Wagner Field, Auxiliary Field 1. Lt Henry Miller, USN, from nearby Naval Air Station Pensacola supervised their takeoff training and accompanied the crews to the launch.

On Mar 25, 1942, after three weeks of intensive training, the 22 remaining B-25-B twin-engine medium bombers of the 17-BG, completed a two-day low-level transcontinental flight and arrived at the Sacramento Air Depot, McClellan Field, California, for final modifications, repairs, and maintenance before an upcoming secret mission. 16 B-25s were flown to Naval Air Station in Alameda, California, on Mar 31.

On Mar 25, 1942, after three weeks of intensive training, the 22 remaining B-25-B twin-engine medium bombers of the 17-BG, completed a two-day low-level transcontinental flight and arrived at the Sacramento Air Depot, McClellan Field, California, for final modifications, repairs, and maintenance before an upcoming secret mission. 16 B-25s were flown to Naval Air Station in Alameda, California, on Mar 31.

Fifteen raiders were the mission force and a 16th aircraft, by last-minute agreement with the Navy, was squeezed onto the deck to be flown off shortly after departure from San Francisco to provide feedback to the Army pilots about takeoff characteristics. The 16th bomber was made part of the mission force instead.

On Apr 1, 1942, the 16 modified bombers, their five-man crews, and Army maintenance personnel, totaling 71 officers and 130 enlisted men, were loaded onto the USS Hornet (CV-8) at the Naval Air Station Alameda. Each aircraft carried four specially constructed 500-pound (250 Kg) bombs. Three of these were high-explosive munitions and one was a bundle of incendiaries. The incendiaries were long tubes, wrapped together in order to be carried in the bomb bay, but designed to separate and scatter over a wide area after release. Five bombs had Japanese friendship medals wired to them, medals awarded by the Japanese government to US servicemen before the war.

Each bomber launched with two .50 Cal (12.7 MM) HMG in an upper turret and a .30 Cal (7.62 MM) LMG in the nose. One simulated gun barrel was mounted in the tail cones, intended to discourage Japanese air attacks from behind. The aircraft were clustered closely and tied down on the Hornet’s flight deck and in the order of launch.

Each bomber launched with two .50 Cal (12.7 MM) HMG in an upper turret and a .30 Cal (7.62 MM) LMG in the nose. One simulated gun barrel was mounted in the tail cones, intended to discourage Japanese air attacks from behind. The aircraft were clustered closely and tied down on the Hornet’s flight deck and in the order of launch.

Operation Planning – Story – January 1942

Things started moving ahead when Capt Francis S. Low, Assistant Chief of Staff for antisubmarine warfare, knocked on US Fleet commander Adm Ernest King’s door on the evening of Jan 10, 1942. Low had spent much of his career in the undersea service before he landed on the admiral’s staff. On that day, he had what he later described as a foolish idea, but given the dark early days of the war, he thought it was at least worth a mention. Francis Low had just returned from Norfolk, where he had observed planes practicing takeoffs on an airfield marked up to resemble a carrier deck.

Things started moving ahead when Capt Francis S. Low, Assistant Chief of Staff for antisubmarine warfare, knocked on US Fleet commander Adm Ernest King’s door on the evening of Jan 10, 1942. Low had spent much of his career in the undersea service before he landed on the admiral’s staff. On that day, he had what he later described as a foolish idea, but given the dark early days of the war, he thought it was at least worth a mention. Francis Low had just returned from Norfolk, where he had observed planes practicing takeoffs on an airfield marked up to resemble a carrier deck.  If the Army has some plane that could take off in that short distance, he asked King, why could we not put a few of them on a carrier and send them to bomb the mainland of Japan? Might even bomb Tokyo! Low waited for the notoriously irascible admiral to brush him off or worse but to his surprise, the Admiral leaned back in his chair thinking. Low, he finally answered, that might be a good idea. Discuss it with Duncan and tell him to report to me! Low immediately phoned Capt Donald Duncan, King’s air operations officer, and arranged for the two of them to meet the next morning. As a fellow US Naval Academy graduate, Duncan held a master’s degree from Harvard. He had served as a navigator on the carrier USS Saratoga (CV-3), executive officer of at the Naval Air Station in Pensacola, and later commanded the first escort carrier of the Navy, the USS Long Island (CVE-1).

If the Army has some plane that could take off in that short distance, he asked King, why could we not put a few of them on a carrier and send them to bomb the mainland of Japan? Might even bomb Tokyo! Low waited for the notoriously irascible admiral to brush him off or worse but to his surprise, the Admiral leaned back in his chair thinking. Low, he finally answered, that might be a good idea. Discuss it with Duncan and tell him to report to me! Low immediately phoned Capt Donald Duncan, King’s air operations officer, and arranged for the two of them to meet the next morning. As a fellow US Naval Academy graduate, Duncan held a master’s degree from Harvard. He had served as a navigator on the carrier USS Saratoga (CV-3), executive officer of at the Naval Air Station in Pensacola, and later commanded the first escort carrier of the Navy, the USS Long Island (CVE-1).

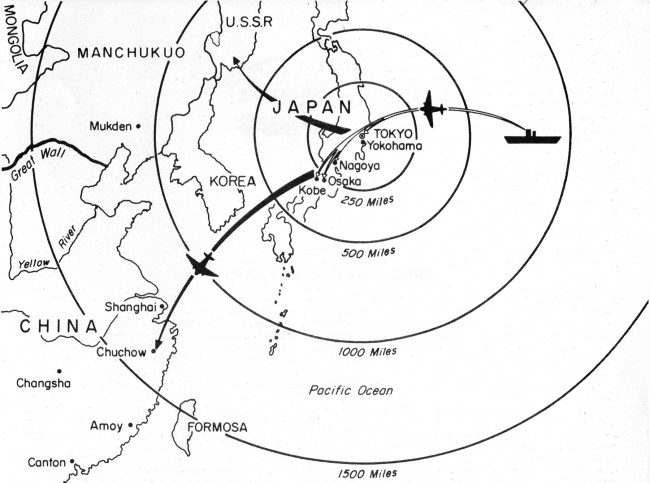

There are two big questions that have to be answered first, Low explained. My first question is as follows. Can an Army medium bomber land aboard a carrier, and can this land-based bomber loaded down with bombs, gas, and crew takes off from a carrier deck? Duncan considered the questions, explaining that a carrier deck was too short for a bomber to land. Furthermore, the fragile tail would never handle the shock of the arresting gear nor would landing bombers fit on the aircraft elevator. My second question is Low pressed I’ll have to get back to you! Duncan started right away, searching for what, if any, bomber could handle such an operation. Low had initially suggested the bombers might return to the carrier and ditch in the water, though Duncan’s study showed it would be better if the planes could fly on to airfields in China. Since intelligence indicated that Japanese patrol planes flew as far as 300 miles offshore, America would need a bomber that could launch well outside that range, strike Tokyo, and still have enough fuel to reach the mainland.

There are two big questions that have to be answered first, Low explained. My first question is as follows. Can an Army medium bomber land aboard a carrier, and can this land-based bomber loaded down with bombs, gas, and crew takes off from a carrier deck? Duncan considered the questions, explaining that a carrier deck was too short for a bomber to land. Furthermore, the fragile tail would never handle the shock of the arresting gear nor would landing bombers fit on the aircraft elevator. My second question is Low pressed I’ll have to get back to you! Duncan started right away, searching for what, if any, bomber could handle such an operation. Low had initially suggested the bombers might return to the carrier and ditch in the water, though Duncan’s study showed it would be better if the planes could fly on to airfields in China. Since intelligence indicated that Japanese patrol planes flew as far as 300 miles offshore, America would need a bomber that could launch well outside that range, strike Tokyo, and still have enough fuel to reach the mainland.

Duncan reviewed the performance data of various Army bombers before settling on the B-25 Mitchell. Not only would its wings likely clear the island, but with modified fuel tanks the B-25 could handle the 2400-mile range (3860 KM) and still carry a large bomb load. Duncan next turned to ships. The Pacific Fleet had just four flattops: the USS Enterprise (CV-6), the USS Lexington (CV-2), the USS Yorktown (CV-5), and the USS Saratoga (CV-3). Another one, the USS Hornet (CV-12), a new carrier, was undergoing shakedown in Virginia. He knew she would report to the Pacific at about the time it would take to finalize such an operation. Low had recommended the use of a single carrier, but Duncan realized the mission would require two. With the cumbersome bombers crowding the Hornet’s flight deck, a second flattop would have to accompany the task force to provide fighter coverage, along with more than a dozen cruisers, destroyers, and oilers. Lastly, a check of historical data revealed a likely window of favorable weather over Tokyo from mid-April to mid-May. When Duncan concluded his preliminary study, he and Low presented the results to King.

Duncan reviewed the performance data of various Army bombers before settling on the B-25 Mitchell. Not only would its wings likely clear the island, but with modified fuel tanks the B-25 could handle the 2400-mile range (3860 KM) and still carry a large bomb load. Duncan next turned to ships. The Pacific Fleet had just four flattops: the USS Enterprise (CV-6), the USS Lexington (CV-2), the USS Yorktown (CV-5), and the USS Saratoga (CV-3). Another one, the USS Hornet (CV-12), a new carrier, was undergoing shakedown in Virginia. He knew she would report to the Pacific at about the time it would take to finalize such an operation. Low had recommended the use of a single carrier, but Duncan realized the mission would require two. With the cumbersome bombers crowding the Hornet’s flight deck, a second flattop would have to accompany the task force to provide fighter coverage, along with more than a dozen cruisers, destroyers, and oilers. Lastly, a check of historical data revealed a likely window of favorable weather over Tokyo from mid-April to mid-May. When Duncan concluded his preliminary study, he and Low presented the results to King.

The aggressive admiral liked what he heard. Go see Gen Arnold about it, and if he agrees with you, ask him to get in touch with me, King ordered. And don’t you two mention this to another soul!